Constructive Friction Or Petty Turf Wars? Organisational Resistance to the Integration of Defence, Diplomacy and Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pakistan in the Danger Zone a Tenuous U.S

Pakistan in the Danger Zone A Tenuous U.S. – Pakistan Relationship Shuja Nawaz The Atlantic Council promotes constructive U.S. leadership and engagement in international affairs based on the central role of the Atlantic community in meeting the international challenges of the 21st century. The Council embodies a non-partisan network of leaders who aim to bring ideas to power and to give power to ideas by: 7 stimulating dialogue and discussion about critical international issues with a view to enriching public debate and promoting consensus on appropriate responses in the Administration, the Congress, the corporate and nonprofit sectors, and the media in the United States and among leaders in Europe, Asia, Africa and the Americas; 7 conducting educational and exchange programs for successor generations of U.S. leaders so that they will come to value U.S. international engagement and have the knowledge and understanding necessary to develop effective policies. Through its diverse networks, the Council builds broad constituencies to support constructive U.S. leadership and policies. Its program offices publish informational analyses, convene conferences among current and/or future leaders, and contribute to the public debate in order to integrate the views of knowledgeable individuals from a wide variety of backgrounds, interests, and experiences. The South Asia Center is the Atlantic Council’s focal point for work on Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Bhutan as well as on relations between these countries and China, Central Asia, Iran, the Arab world, Europe and the U.S. As part of the Council’s Asia program, the Center seeks to foster partnerships with key institutions in the region to establish itself as a forum for dialogue between decision makers in South Asia, the U.S. -

Acquisitions List September 2009

ACQUISITIONS LIST (NEW BOOKS AND JOURNAL ARTICLES) SEPTEMBER 2009 – SEPTEMBRE 2009 LISTE D’ACQUISITIONS (NOUVEAUX LIVRES ET ARTICLES DE REVUES) · To contact us : · NATO Library Public Diplomacy Division Room Nb123 1110 Brussels Belgium Tel. : 32.2.707.44.14 Fax : 32.2.707.42.49 E-mail : [email protected] · Intranet : http://hqweb.hq.nato.int/oip/library/ · Internet : http://www.nato.int/library · How to borrow items from the list below : As a member of the NATO HQ staff you can borrow books (Type: M) for one month, journals (Type: ART) and reference works (Type: REF) for one week. Individuals not belonging to NATO staff can borrow books through their local library via the interlibrary loan system. · How to obtain the Library publications : All Library publications are available both on the NATO Intranet and Internet websites. -------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- · Pour nous contacter : · Bibliothèque de l'OTAN Division de la Diplomatie Publique Bureau Nb123 1110 Bruxelles Belgique Tél. : 32.2.707.44.14 Télécopieur : 32.2.707.42.49 E-mail : [email protected] · Intranet : http://hqweb.hq.nato.int/oip/library/ · Internet : http://www.nato.int/library · Comment emprunter les documents cités ci-dessous : En tant que membre du personnel de l'OTAN vous pouvez emprunter les livres (Type: M) pour un mois, les revues (Type: ART) et les ouvrages de référence (Type: REF) pour une semaine. Les personnes n'appartenant pas au personnel d l'OTAN peuvent s'adresser à leur bibliothèque locale et emprunter les livres via le système de prêt interbibliothèques. · Comment obtenir les publications de la Bibliothèque : Toutes les publications de la Bibliothèque sont disponibles sur les sites Intranet et Internet de l’OTAN. -

The Pugwash Newsletter and the Change

NEWSLETTER issued by the Council of the Pugwash Conferences on Science and World Affairs Nobel Peace Prize 1995 Pugwash 50th Anniversary, Thinker’s Lodge, Pugwash, Nova Scotia, July 2007 Volume 44 ½ Number 1 ½ July 2007 TABLE OF CONTENTS TO THE PUGWASH COMMUNITY : . 1 SPECIAL SECTION Pugwash Meeting no. 326 “Revitalizing Nuclear Disarmament,” The 50th Anniversary of the Pugwash Conferences Co-sponsored by the Pugwash Conferences and the Middle Powers Initiative, Pugwash, Nova Scotia, Canada, 5 –7 July 2007 Communique from the Pugwash 50th Anniversary Workshop . 3 Greetings from Prime Minister Stephen Harper and Nova Scotia Premier Rodney MacDonald . 5 Program for the Pugwash 50th Anniversary Events . 7 Welcoming Remarks: Paolo Cotta-Ramusino, Douglas Roche, Raymond Szabo . 8 Workshop Report . 12 Speech by Hiroshima Mayor Tadatoshi Akiba . 18 Participant List . 23 Media Coverage, International Herald Tribune . 24 REPORTS ON RECENT PUGWASH WORKSHOPS Pugwash meeting no. 324 . 25 26th Workshop of the Pugwash Study Group on the Implementation of the Chemical and Biological Weapons Conventions: 10 Years of the OPCW: Taking Stock and Looking Forward Pu gwash Noordwijk, The Netherlands, 17-18 March 2007 Volume 44 ½ Number 1 Pugwash Meeting no. 325 . 35 July 2007 Pugwash Workshop on Iraq Erbil, Kurdistan, Iraq, 11-13 May 2007 Editor: NATIONAL PUGWASH GROUPS: . 41 Jeffrey Boutwell Canadian Pugwash Celebrates the 50th Anniversary of Pugwash Research Assistant: INTERNATIONAL STUDENT/YOUNG PUGWASH: . 44 Erin Blankenship International Student Young Pugwash & M S Swaminathan Research Foundation Consultation on “Food Security: A Great Threat to Human Security” Design and Layout: Chennai, India, 31 January—1 February 2007 Anne Read OBITUARIES: . -

Basra: Strategic Dilemmas and Force Options

CASE STUDY NO. 8 COMPLEX OPERATIONS CASE STUDIES SERIES Basra: Strategic Dilemmas and Force Options John Hodgson The Pennsylvania State University KAREN GUTTIERI SERIES EDITOR Naval Postgraduate School COMPLEX OPERATIONS CASE STUDIES SERIES Complex operations encompass stability, security, transition and recon- struction, and counterinsurgency operations and operations consisting of irregular warfare (United States Public Law No 417, 2008). Stability opera- tions frameworks engage many disciplines to achieve their goals, including establishment of safe and secure environments, the rule of law, social well- being, stable governance, and sustainable economy. A comprehensive approach to complex operations involves many elements—governmental and nongovernmental, public and private—of the international community or a “whole of community” effort, as well as engagement by many different components of government agencies, or a “whole of government” approach. Taking note of these requirements, a number of studies called for incentives to grow the field of capable scholars and practitioners, and the development of resources for educators, students and practitioners. A 2008 United States Institute of Peace study titled “Sharing the Space” specifically noted the need for case studies and lessons. Gabriel Marcella and Stephen Fought argued for a case-based approach to teaching complex operations in the pages of Joint Forces Quarterly, noting “Case studies force students into the problem; they put a face on history and bring life to theory.” We developed -

Section 15.1 Civilian Personnel

SECTION 15.1 CIVILIAN PERSONNEL Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................. 245 Civilian outreach event .......................................................................................... 245 Pre‑invasion planning and preparation ........................................................................ 246 ORHA ..................................................................................................................... 247 DFID humanitarian advisers .................................................................................. 249 The British Embassy Baghdad .............................................................................. 250 MOD civilian support to Op TELIC ......................................................................... 252 UK civilian presence during the Coalition Occupation of Iraq ...................................... 255 UK civilian deployments to ORHA ......................................................................... 255 The CPA and the return to a “war footing” ............................................................. 263 The impact of deteriorating security ....................................................................... 272 The British Offices in Baghdad and Basra ............................................................. 291 Preparations for the transfer of sovereignty ........................................................... 294 The post‑CPA UK civilian presence in Iraq -

Strategic Dialogue on South Asia Conference Report

STRATEGIC DIALOGUE ON SOUTH ASIA CONFERENCE REPORT International conference organized jointly by CERI-Sciences Po (Paris) and the Brookings Institution (Washington, DC) Paris, June 29-30, 2006 The third “Allies conference” on South Asia was held at the Centre d’Etudes et de Recherches Internationales in Paris on 29 and 30 June 2006. It followed two earlier conferences, held at Brookings in Washington DC in 2003 and 2005. This meeting brought together South Asian experts and concerned government officials –participating in their private capacity – from nine countries: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Poland, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the United States. The conference explored two major issue-areas. The first was South Asia’s setting in the wider world, including China’s role, and sources of tension from South Asia’s periphery. The second set of issues took a global perspective, in which nuclear and economic factors were examined, as were the policies of the US, Europe and the EU-India partnership, and Japan’s South Asia policies. These talks were off-the-record and private, allowing for frank discussion. They clarified regional policies and trends, as well as the approaches to South Asia of major non-regional powers. This report summarizes the conference proceedings and notes some major conclusions that emerged from the discussions. Part I presents the conference program and the list of participants. Part II sets forth the major policy-related conclusions reached at the meeting. Part III is a more detailed, analytical summary of the discussion itself. The conference was organized with the support of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs through its Policy Planning Department (Centre d’Analyses et de Prévisions, CAP) and the Secretariat-General of National Defense (Secrétariat Général de la Défense Nationale, SGDN). -

The Future of Pakistan

FOREIGN POLICY at Brookings The Future of Pakistan Stephen P. Cohen South Asia Initiative THE FUTURE OF PAKISTAN Stephen P. Cohen The Brookings Institution Washington, D.C. January 2011 1 ABOUT THE AUTHOR Stephen P. Cohen is a senior fellow in Foreign Policy at Brookings. He came to Brookings in 1998 after a long career as professor of political science and history at the University of Illinois. Dr. Cohen previously served as scholar-in-residence at the Ford Foundation in New Delhi and as a member of the Policy Planning Staff of the U.S. State Department. He has also taught at universities in India, Japan and Singapore. He is currently a member of the National Academy of Science’s Committee on International Security and Arms Control. Dr. Cohen is the author or editor of more than eleven books, focusing primarily on South Asian security issues. His most recent book, Arming without Aiming: India modernizes its Military (co- authored with Sunil Das Gupta, 2010), focuses on India’s military expansion. Dr. Cohen received Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees at the University of Chicago, and a PhD from the University of Wisconsin. EDITOR’S NOTE This essay and accompanying papers are also available at http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2010/09_bellagio_conference_papers.aspx 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE………………………………………………………………………….. 1 INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………….3 PAKISTAN TO 2011………………………………………………………………. 5 FOUR CLUSTERS I: Demography, Education, Class, and Economics………………………….. 16 II: Pakistan’s Identity……………………………………………………….. 23 III: State Coherence………………………………………………………… 27 IV: External and Global Factors…………………………………………...... 34 SCENARIOS AND OUTCOMES…………………………………………………. 43 CONCLUSIONS…………………………………………………………………… 50 SIX WARNING SIGNS……………………………………………………………. 51 POLICY: BETWEEN HOPE AND DESPAIR……………………………………. -

The United Kingdom's 2001-2003 Preparation for the Invasion of Iraq

1 Between Dream and Deed: The United Kingdom’s 2001-2003 Preparation for the Invasion of Iraq by KAROLIEN EMMA MICHELLE KEARY Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS at DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL POLITICS ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY 2017 2 Between Dream and Deed: The United Kingdom’s 2001-2003 Preparation for the Invasion of Iraq by KAROLIEN EMMA MICHELLE KEARY Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN INTERNATIONAL POLITICS at DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL POLITICS ABERYSTWYTH UNIVERSITY 2017 3 To my grandmothers, who should have had a chance to study geography and languages. 4 Declarations This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Where correction services have been used, the extent and nature of the correction is clearly marked in a footnote. Other sources are acknowledged by footnotes giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. I give consent for my thesis, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for interlibrary loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. The word count of the thesis is 90,397 words. The views expressed in this work are the author’s own and do not reflect the official position of the Federal Public Service of Foreign Affairs or the Belgian government. 5 Acknowledgements When four years ago I pleaded with the department to get Hidemi as a new supervisor, I knew working with him would be an intellectual delight and suspected it would change the way I understood the world. -

Newsletter 22

BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ NEWSLETTER NO. 22 November 2008 BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ (GERTRUDE BELL MEMORIAL) REGISTERED CHARITY NO. 219948 BRITISH INSTITUTE FOR THE STUDY OF IRAQ 10, CARLTON HOUSE TERRACE LONDON SW1Y 5AH, UK E-mail: [email protected] Tel. + 44 (0) 20 7969 5274 Fax + 44 (0) 20 7969 5401 Web-site: http://www.britac.ac.uk/institutes/iraq/ The next BISI Newsletter will be published in May 2009. Brief contributions are welcomed on recent research, publications and events. They should be sent to BISI by post or e-mail to arrive by 15 April 2009. BISI Administrator Joan Porter MacIver edits the Newsletter. Cover: Our new BISI logo with the beautiful calligraphy of our new name in was drawn by Taha al-Hiti through the (اﻟﻤﻌﻬﺪ اﻟﺒﺮﻳﻄﺎﻧﻲ ﻟﺪراﺳﺔ اﻟﻌﺮاق) Arabic assistance of BISI Council member, Sir Terence Clark KBE. Taha al-Hiti was born in Baghdad in 1971 and began calligraphy at the age of six. He later studied under the master calligrapher Abbas al-Baghdady, who awarded him in 2005 his ‘Ijaza’ (licence). Meanwhile he graduated in architecture from Baghdad University and, after post-graduate studies in Islamic architecture in Vienna, he moved to London, where he practised as an architect for several years. He is at present senior architect/project manager on major building projects for a British company in Abu Dhabi. He has held exhibitions of his calligraphy in Baghdad, London, Abu Dhabi and Dubai. The British Institute for the Study of Iraq is very grateful to Mr al-Hiti for providing us with such a wonderful example of his calligraphy for our logo. -

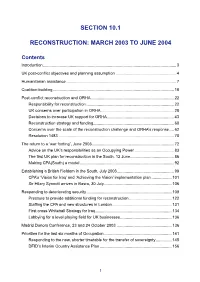

Section 10.1 Reconstruction

SECTION 10.1 RECONSTRUCTION: MARCH 2003 TO JUNE 2004 Contents Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 3 UK post-conflict objectives and planning assumption ...................................................... 4 Humanitarian assistance .................................................................................................. 7 Coalition-building ............................................................................................................ 18 Post-conflict reconstruction and ORHA .......................................................................... 22 Responsibility for reconstruction .............................................................................. 22 UK concerns over participation in ORHA ................................................................. 28 Decisions to increase UK support for ORHA ............................................................ 43 Reconstruction strategy and funding ........................................................................ 60 Concerns over the scale of the reconstruction challenge and ORHA’s response .... 62 Resolution 1483 ....................................................................................................... 70 The return to a ‘war footing’, June 2003 ......................................................................... 72 Advice on the UK’s responsibilities as an Occupying Power ................................... 83 The first UK plan -

PRISM Vol 1, No 2

PRISM❖ Vol. 1, no. 2 03/2010 PRISM Vol. 1, no. 2 ❖ 03/2010 www.ndu.edu A JOURNAL OF THE CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS PRISM ABOUT CENTER FOR COMPLEX OPERATIONS (CCO) CCO WAS ESTABLISHED TO: PRISM is published by the National Defense University Press for the Center for ❖ Serve as an information clearinghouse and knowledge Enhancing the U.S. Government’s Ability to manager for complex operations training and education, PUBLISHER Complex Operations. PRISM is a security studies journal chartered to inform members of U.S. Federal Agencies, allies, and other partners on complex and Prepare for Complex Operations acting as a central repository for information on areas Dr. Hans Binnendijk integrated national security operations; reconstruction and nationbuilding; relevant such as training and curricula, training and education pro- CCO, located within the Center for Technology and policy and strategy; lessons learned; and developments in training and education vider institutions, complex operations events, and subject EDITOR AND RESEARCH DIRECTOR National Security Policy (CTNSP) at National Defense to transform America’s security and development apparatus to meet tomorrow’s matter experts University, links U.S. Government education and training Michael Miklaucic challenges better while promoting freedom today. institutions, including related centers of excellence, ❖ Develop a complex operations training and education com- lessons learned programs, and academia, to foster unity munity of practice to catalyze innovation and development DEVELOPMENTAL EDITOR of effort in reconstruction and stability operations, of new knowledge, connect members for networking, share Melanne A. Civic, Esq. COMMUNICATIONS counterinsurgency, and irregular warfare—collectively existing knowledge, and cultivate foundations of trust and called “complex operations.” The Department of Defense, habits of collaboration across the community Constructive comments and contributions are important to us. -

The UK's Foreign Policy Approach to Afghanistan and Pakistan

House of Commons Foreign Affairs Committee The UK's foreign policy approach to Afghanistan and Pakistan Fourth Report of Session 2010–11 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes, oral and written evidence Additional written evidence is contained in Volume II, available on the Committee website at www.parliament.uk/facom Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 9 February 2011 HC 514 Published on 2 March 2011 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £23.00 The Foreign Affairs Committee The Foreign Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and its associated agencies. Current membership Richard Ottaway (Conservative, Croydon South) (Chair) Rt Hon Bob Ainsworth (Labour, Coventry North East) Mr John Baron (Conservative, Basildon and Billericay) Rt Hon Sir Menzies Campbell (Liberal Democrats, North East Fife) Rt Hon Ann Clwyd (Labour, Cynon Valley) Mike Gapes (Labour, Ilford South) Andrew Rosindell (Conservative, Romford) Mr Frank Roy (Labour, Motherwell and Wishaw) Rt Hon Sir John Stanley (Conservative, Tonbridge and Malling) Rory Stewart (Conservative, Penrith and The Border) Mr Dave Watts (Labour, St Helens North) The following Member was also a member of the Committee during the parliament: Emma Reynolds (Labour, Wolverhampton North East) Powers The Committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publication The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House.