Gastrointestinal Bleeding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

081999 Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

The New England Journal of Medicine Current Concepts Systemic activation+ of coagulation DISSEMINATED INTRAVASCULAR COAGULATION Intravascular+ Depletion of platelets+ deposition of fibrin and coagulation factors MARCEL LEVI, M.D., AND HUGO TEN CATE, M.D. Thrombosis of small+ Bleeding and midsize vessels+ ISSEMINATED intravascular coagulation is and organ failure characterized by the widespread activation Dof coagulation, which results in the intravas- Figure 1. The Mechanism of Disseminated Intravascular Coag- cular formation of fibrin and ultimately thrombotic ulation. occlusion of small and midsize vessels.1-3 Intravascu- Systemic activation of coagulation leads to widespread intra- lar coagulation can also compromise the blood sup- vascular deposition of fibrin and depletion of platelets and co- agulation factors. As a result, thrombosis of small and midsize ply to organs and, in conjunction with hemodynam- vessels may occur, contributing to organ failure, and there may ic and metabolic derangements, may contribute to be severe bleeding. the failure of multiple organs. At the same time, the use and subsequent depletion of platelets and coag- ulation proteins resulting from the ongoing coagu- lation may induce severe bleeding (Fig. 1). Bleeding may be the presenting symptom in a patient with disseminated intravascular coagulation, a factor that can complicate decisions about treatment. TABLE 1. COMMON CLINICAL CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH DISSEMINATED ASSOCIATED CLINICAL CONDITIONS INTRAVASCULAR COAGULATION. AND INCIDENCE Sepsis Infectious Disease Trauma Serious tissue injury Disseminated intravascular coagulation is an ac- Head injury Fat embolism quired disorder that occurs in a wide variety of clin- Cancer ical conditions, the most important of which are listed Myeloproliferative diseases in Table 1. -

What Everyone Should Know to Stop Bleeding After an Injury

What Everyone Should Know to Stop Bleeding After an Injury THE HARTFORD CONSENSUS The Joint Committee to Increase Survival from Active Shooter and Intentional Mass Casualty Events was convened by the American College of Surgeons in response to the growing number and severity of these events. The committee met in Hartford Connecticut and has produced a number of documents with rec- ommendations. The documents represent the consensus opinion of a multi-dis- ciplinary committee involving medical groups, the military, the National Security Council, Homeland Security, the FBI, law enforcement, fire rescue, and EMS. These recommendations have become known as the Hartford Consensus. The overarching principle of the Hartford Consensus is that no one should die from uncontrolled bleeding. The Hartford Consensus recommends that all citizens learn to stop bleeding. Further information about the Hartford Consensus and bleeding control can be found on the website: Bleedingcontrol.org 2 SAVE A LIFE: What Everyone Should Know to Stop Bleeding After an Injury Authors: Peter T. Pons, MD, FACEP Lenworth Jacobs, MD, MPH, FACS Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge the contributions of Michael Cohen and James “Brooks” Hart, CMI to the design of this manual. Some images adapted from Adam Wehrle, EMT-P and NAEMT. © 2017 American College of Surgeons CONTENTS SECTION 1 3 ■ Introduction ■ Primary Principles of Trauma Care Response ■ The ABCs of Bleeding SECTION 2 5 ■ Ensure Your Own Safety SECTION 3 6 ■ A – Alert – call 9-1-1 SECTION 4 7 ■ B – Bleeding – find the bleeding injury SECTION 5 9 ■ C – Compress – apply pressure to stop the bleeding by: ■ Covering the wound with a clean cloth and applying pressure by pushing directly on it with both hands, OR ■Using a tourniquet, OR ■ Packing (stuff) the wound with gauze or a clean cloth and then applying pressure with both hands SECTION 6 13 ■ Summary 2 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Stop the Bleed: Bleeding Control for the Injured information booklet. -

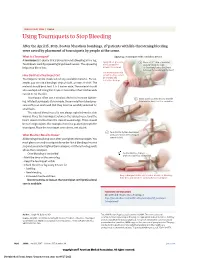

Using Tourniquets to Stop Bleeding

JAMA PATIENT PAGE | Trauma Using Tourniquets to Stop Bleeding After the April 15, 2013, Boston Marathon bombings, 27 patients with life-threatening bleeding were saved by placement of tourniquets by people at the scene. What Is a Tourniquet? Applying a tourniquet with a windlass device A tourniquet is a device that is placed around a bleeding arm or leg. Apply direct pressure 1 Place a 2-3” strip of material Tourniquets work by squeezing large blood vessels. The squeezing to the wound for about 2” from the edge helps stop blood loss. at least 15 minutes. of the wound over a long bone between the wound and the heart. Use a tourniquet only How Do I Put a Tourniquet On? when bleeding cannot be stopped and Tourniquets can be made out of any available material. For ex- is life threatening. ample, you can use a bandage, strip of cloth, or even a t-shirt. The material should be at least 2 to 3 inches wide. The material should also overlap itself. Using thin straps or material less than 2 inches wide can rip or cut the skin. Tourniquets often use a windlass device to increase tighten- 2 Insert a stick or other strong, straight ing. Inflated tourniquets (for example, those made from blood pres- item into the knot to act as a windlass. sure cuffs) can work well. But they must be carefully watched for small leaks. The injured blood vessel is not always right below the skin wound. Place the tourniquet between the injured vessel and the heart, about 2 inches from the closest wound edge. -

ER Guide to Bleeding Disorders

Bleeding disorders ER guide to bleeding disorders 1 Table of contents 4 General Guidelines 4–5 national Hemophilia Foundation guidelines 5–10 Treatment options 10 HemopHilia a Name:__________________________________________________________________________________________________ 10–11 national Hemophilia Foundation guidelines Address:________________________________________________________________________________________________ 12 dosage chart Phone:__________________________________________________________________________________________________ 14–15 Treatment products 16 HemopHilia B In case of emergency, contact: ______________________________________________________________________________ 16 national Hemophilia Foundation guidelines Relation to patient:________________________________________________________________________________________ 17 dosage chart 18 Treatment products 19 HemopHilia a or B with inHiBiTors Diagnosis: Hemophilia A: Mild Moderate Severe 20 national Hemophilia Foundation guidelines Inhibitors Inhibitors Bethesda units (if known) ____________________________________ 21 Treatment products Hemophilia B: Mild Moderate Severe 22–23 Von willeBrand disease Inhibitors Inhibitors Bethesda units (if known) ____________________________________ 23–24 national Hemophilia Foundation guidelines von Willebrand disease: Type 1 Type 2 Type 3 Platelet type 25 Treatment products 27 Bibliography Preferred product:_________________________________________________________________________________________ Dose for life-threatening -

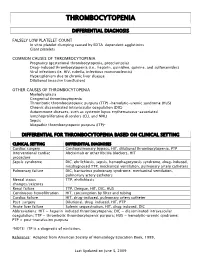

Thrombocytopenia.Pdf

THROMBOCYTOPENIA DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS FALSELY LOW PLATELET COUNT In vitro platelet clumping caused by EDTA-dependent agglutinins Giant platelets COMMON CAUSES OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA Pregnancy (gestational thrombocytopenia, preeclampsia) Drug-induced thrombocytopenia (i.e., heparin, quinidine, quinine, and sulfonamides) Viral infections (ie. HIV, rubella, infectious mononucleosis) Hypersplenism due to chronic liver disease Dilutional (massive transfusion) OTHER CAUSES OF THROMBOCYTOPENIA Myelodysplasia Congenital thrombocytopenia Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) -hemolytic-uremic syndrome (HUS) Chronic disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) Autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus-associated lymphoproliferative disorders (CLL and NHL) Sepsis Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP)* DIFFERENTIAL FOR THROMBOCYTOPENIA BASED ON CLINICAL SETTING CLINICAL SETTING DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSES Cardiac surgery Cardiopulmonary bypass, HIT, dilutional thrombocytopenia, PTP Interventional cardiac Abciximab or other IIb/IIIa blockers, HIT procedure Sepsis syndrome DIC, ehrlichiosis, sepsis, hemophagocytosis syndrome, drug-induced, misdiagnosed TTP, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery catheters Pulmonary failure DIC, hantavirus pulmonary syndrome, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary artery catheters Mental status TTP, ehrlichiosis changes/seizures Renal failure TTP, Dengue, HIT, DIC, HUS Continuous hemofiltration HIT, consumption by filter and tubing Cardiac failure HIT, drug-induced, pulmonary artery catheter Post-surgery -

Ten Patient Stories Illustrating the Extraordinarily Diverse Clinical Features of Patients with Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Severe ADAMTS13 Deficiency

Journal of Clinical Apheresis 27:302–311 (2012) Ten Patient Stories Illustrating the Extraordinarily Diverse Clinical Features of Patients With Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Severe ADAMTS13 Deficiency James N. George,* Qiaofang Chen, Cassie C. Deford, and Zayd Al-Nouri Department of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, College of Public Health, Department of Medicine, College of Medicine, The University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma Patients with thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and severe ADAMTS13 deficiency are often consid- ered to have typical clinical features. However, our experience is that there is extraordinary diversity of the pre- senting features and the clinical courses of these patients. This diversity is illustrated by descriptions of 10 patients. The patients illustrate that ADAMTS13 activity may be normal initially but severely deficient in subse- quent episodes. Patients with established diagnoses of systemic infection as the cause of their clinical features may have undetectable ADAMTS13 activity. Patients may have a prolonged prodrome of mild symptoms with only microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia or they may have the sudden onset of critical ill- ness with multiple organ involvement. Patients may die rapidly or recover rapidly; they may require minimal treatment or extensive and prolonged treatment. Patients may have acute and severe neurologic abnormalities before microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia occur. Patients may have concurrent TTP and systemic lupus erythematosus. Patients may have hereditary ADAMTS13 deficiency as the etiology of their TTP rather than acquired autoimmune ADAMTS13 deficiency. These patients’ stories illustrate the clinical spectrum of TTP with ADAMTS13 deficiency and emphasize the difficulties of clinical diagnosis. J. Clin. -

Modern Management of Traumatic Hemothorax

rauma & f T T o re l a t a m n r e u n o t J Mahoozi, et al., J Trauma Treat 2016, 5:3 Journal of Trauma & Treatment DOI: 10.4172/2167-1222.1000326 ISSN: 2167-1222 Review Article Open Access Modern Management of Traumatic Hemothorax Hamid Reza Mahoozi, Jan Volmerig and Erich Hecker* Thoraxzentrum Ruhrgebiet, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Evangelisches Krankenhaus, Herne, Germany *Corresponding author: Erich Hecker, Thoraxzentrum Ruhrgebiet, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Evangelisches Krankenhaus, Herne, Germany, Tel: 0232349892212; Fax: 0232349892229; E-mail: [email protected] Rec date: Jun 28, 2016; Acc date: Aug 17, 2016; Pub date: Aug 19, 2016 Copyright: © 2016 Mahoozi HR. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Abstract Hemothorax is defined as a bleeding into pleural cavity. Hemothorax is a frequent manifestation of blunt chest trauma. Some authors suggested a hematocrit value more than 50% for differentiation of a hemothorax from a sanguineous pleural effusion. Hemothorax is also often associated with penetrating chest injury or chest wall blunt chest wall trauma with skeletal injury. Much less common, it may be related to pleural diseases, induced iatrogenic or develop spontaneously. In the vast majority of blunt and penetrating trauma cases, hemothoraces can be managed by relatively simple means in the course of care. Keywords: Traumatic hemothorax; Internal chest wall; Cardiac Hemodynamic response injury; Clinical manifestation; Blunt chest-wall injuries; Blunt As above mentioned the hemodynamic response is a multifactorial intrathoracic injuries; Penetrating thoracic trauma response and depends on severity of hemothorax according to its classification. -

Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura (ITP) — Adult Conditions for Which Ivig Has an Established Therapeutic Role

Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) — adult Conditions for which IVIg has an established therapeutic role. Specific Conditions Newly Diagnosed Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Persistent Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Chronic Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) Evans syndrome ‐ with significant Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) ‐ adult Indication for IVIg Use Newly diagnosed ITP — initial Ig therapy ITP in pregnancy — initial Ig therapy ITP with life‐threatening haemorrhage or the potential for life‐threatening haemorrhage Newly diagnosed or persistent ITP — subsequent therapy (diagnosis <12 months) Refractory persistent or chronic ITP — splenectomy failed or contraindicated and second‐line agent unsuccessful Subsequent or ongoing treatment for ITP responders during pregnancy and the postpartum period ITP and inadequate platelet count for planned surgery HIV‐associated ITP Level of Evidence Evidence of probable benefit – more research needed (Category 2a) Description and Diagnostic Immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is a reduction in platelet count Criteria (thrombocytopenia) resulting from shortened platelet survival due to anti‐platelet antibodies, reduced platelet production due to immune induced reduced megakaryopoeisis and/or immune mediated direct platelet lysis. When counts are very low (less than 30x109/L), bleeding into the skin (purpura) and mucous membranes can occur. Bone marrow platelet production (megakaryopoiesis) is morphologically normal. In some cases, there is additional impairment of platelet function related to antibody binding to glycoproteins on the platelet surface. It is a common finding in patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) disease, and while it may be found at any stage of the infection, its prevalence increases as HIV disease advances. Around 80 percent of adults with ITP have the chronic form of disease. -

Treatment of Hemothorax in the Era Of€The€Minimaly Invasive Surgery

Mil. Med. Sci. Lett. (Voj. Zdrav. Listy) 2019, 88(4), 180-187 ISSN 0372-7025 (Print) ISSN 2571-113X (Online) DOI: 10.31482/mmsl.2019.011 Since 1925 REVIEW ARTICLE TREATMENT OF HEMOTHORAX IN THE ERA OF THE MINIMALY INVASIVE SURGERY Radek Pohnán 1,2 , Šárka Blažková 2, Vladislav Hytych 2, Petr Svoboda 1, Michal Makeľ 1, Iva Holmquist 3,4 and Miroslav Ryska 1 1 Department of Surgery, Central Military Hospital – Faculty Military Hospital, 2nd Faculty of Medicine, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic 2 Department of Thoracic Surgery, Thomayer's Hospital, 140 59 Prague, Czech Republic 3 Emory University Hospital Midtown, Maternity Center, Atlanta, Georgia, USA 4 Department of Epidemiology, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Defence, Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic Received 19th July 2018. Accepted 13th May 2019. On-line 6th December 2019. Summary Hemothorax is a frequent clinical situation often associated with chest injury or with iatrogenic lesions. Spontaneous hemothorax is uncommon and among its cause may include coagulation disorders, pleural, pulmonary or vascular pathology. Diagnostics is based on radiography or ultrasound and thoracentesis which may be also therapeutic solution. The majority of hemothoraxes can be managed non-operatively but hemodynamic instability, the volume of evacuated blood and persisting blood loss or persisting hemothorax require surgery. A surgical approach may vary from open thoracotomy to rapidly developing minimally invasive methods - video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) and videothoracoscopy (VTS). Key words: hemothorax; surgery; VATS; thoracotomy Introduction Hemothorax is a pathological collection of the blood within the pleural cavity. Hemothorax most frequently origin in a thoracic injury but the exact incidence is not known. -

Gastrointestinal Bleeding Gary A

Article gastroenterology Gastrointestinal Bleeding Gary A. Neidich, MD* Educational Gaps Sarah R. Cole, MD* 1. Pediatricians should be familiar with diseases that may present with gastrointestinal bleeding in patients at varying ages. Author Disclosure 2. Pediatricians should be aware of newer technologies for the identification and therapy Drs Neidich and Cole of gastrointestinal bleeding sources. have disclosed no 3. Pediatricians should be familiar with polyps that have and do not have an increased financial relationships risk of malignant transformation. relevant to this article. 4. Pediatricians should be familiar with medications used in the treatment of children This commentary does with gastrointestinal bleeding. not contain a discussion of an Objectives After completing this article, readers should be able to: unapproved/ investigative use of 1. Formulate a diagnostic and management plan for children with gastrointestinal a commercial product/ bleeding. device. 2. Describe newer techniques and their limitations for the identification of bleeding, including small intestinal capsule endoscopy and small intestinal enteroscopy. 3. Differentiate common and less common causes of gastrointestinal bleeding in children of varying ages. 4. Identify types of polyps that may present in childhood and which of these have malignant potential. Introduction An 11-year-old boy is seen in the emergency department after fainting at home. He has a 2-day history of headache and dizziness. Epigastric pain has been present during the past 2 days. His pulse is 150 beats per minute, and his blood pressure is 90/50 mm Hg. An in- travenous bolus of normal saline is administered; his hemoglobin level is 8.1 g/dl (81 g/L). -

Spontaneous Hemopericardium Leading to Cardiac Tamponade in a Patient with Essential Thrombocythemia

SAGE-Hindawi Access to Research Cardiology Research and Practice Volume 2011, Article ID 247814, 3 pages doi:10.4061/2011/247814 Case Report Spontaneous Hemopericardium Leading to Cardiac Tamponade in a Patient with Essential Thrombocythemia Anand Deshmukh,1, 2 Shanmuga P. Subbiah,3 Sakshi Malhotra,4 Pooja Deshmukh,4 Suman Pasupuleti,1 and Syed Mohiuddin1, 4 1 Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68131, USA 2 Creighton Cardiac Center, 3006 Webster Street, Omaha, NE 68131, USA 3 Department of Hematology and Oncology, Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68131, USA 4 Department of Internal Medicine, Creighton University Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68131, USA Correspondence should be addressed to Anand Deshmukh, [email protected] Received 30 October 2010; Accepted 29 December 2010 Academic Editor: Syed Wamique Yusuf Copyright © 2011 Anand Deshmukh et al. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Acute cardiac tamponade requires urgent diagnosis and treatment. Spontaneous hemopericardium leading to cardiac tamponade as an initial manifestation of essential thrombocythemia (ET) has never been reported in the literature. We report a case of a 72-year-old Caucasian female who presented with spontaneous hemopericardium and tamponade requiring emergent pericardiocentesis. The patient was subsequently diagnosed to have ET. ET is characterized by elevated platelet counts that can lead to thrombosis but paradoxically it can also lead to a bleeding diathesis. Physicians should be aware of this complication so that timely life-saving measures can be taken if this complication arises. -

The Voice of the Patient: Hemophilia A, Hemophilia B, Von Willebrand Disease and Other Heritable Bleeding Disorders

The Voice of the Patient A series of reports from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative Hemophilia A, Hemophilia B, von Willebrand Disease and Other Heritable Bleeding Disorders Public Meeting: September 22, 2014 Report Date: May 2016 Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) 1 Table of Contents Introduction ..............................................................................................................3 Overview of bleeding disorders ................................................................................................ 3 Meeting overview ..................................................................................................................... 4 Report overview and key themes .............................................................................................. 5 Topic 1: Disease Symptoms and Daily Impacts That Matter Most to Patients 6 Perspectives on symptoms ........................................................................................................ 7 Perspectives on the overall impact of bleeding disorders on daily life ..................................... 9 Topic 2: Patient Perspectives on Current Approaches to Treatments ............11 Perspectives on current treatment for conditions or symptoms .............................................. 12 Perspectives on an ideal treatment .......................................................................................... 16