Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiating Between Anxiety, Syncope & Anaphylaxis

Differentiating between anxiety, syncope & anaphylaxis Dr. Réka Gustafson Medical Health Officer Vancouver Coastal Health Introduction Anaphylaxis is a rare but much feared side-effect of vaccination. Most vaccine providers will never see a case of true anaphylaxis due to vaccination, but need to be prepared to diagnose and respond to this medical emergency. Since anaphylaxis is so rare, most of us rely on guidelines to assist us in assessment and response. Due to the highly variable presentation, and absence of clinical trials, guidelines are by necessity often vague and very conservative. Guidelines are no substitute for good clinical judgment. Anaphylaxis Guidelines • “Anaphylaxis is a potentially life-threatening IgE mediated allergic reaction” – How many people die or have died from anaphylaxis after immunization? Can we predict who is likely to die from anaphylaxis? • “Anaphylaxis is one of the rarer events reported in the post-marketing surveillance” – How rare? Will I or my colleagues ever see a case? • “Changes develop over several minutes” – What is “several”? 1, 2, 10, 20 minutes? • “Even when there are mild symptoms initially, there is a potential for progression to a severe and even irreversible outcome” – Do I park my clinical judgment at the door? What do I look for in my clinical assessment? • “Fatalities during anaphylaxis usually result from delayed administration of epinephrine and from severe cardiac and respiratory complications. “ – What is delayed? How much time do I have? What is anaphylaxis? •an acute, potentially -

Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) and Thrombosis: the Critical Role of the Lab Paul Riley, Phd, MBA, Diagnostica Stago, Inc

Generate Knowledge Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation (DIC) and Thrombosis: The Critical Role of the Lab Paul Riley, PhD, MBA, Diagnostica Stago, Inc. Learning Objectives Describe the basic pathophysiology of DIC Demonstrate a diagnostic and management approach for DIC Compare markers of thrombin & plasmin generation in DIC, including D-Dimer, fibrin monomers (FM; aka soluble fibrin monomers, SFM), and fibrin degradation products (FDPs; aka fibrin split products, FSPs) Correlate DIC theory and testing to specific clinical cases DIC = Death is Coming What is Hemostasis? Blood Circulation Occurs through blood vessels ARTERIES The heart pumps the blood Arteries carry oxygenated blood away from the heart under high pressure VEINS Veins carry de-oxygenated blood back to the heart under low pressure Hemostasis The mechanism that maintains blood fluidity Keeps a balance between bleeding and clotting 2 major roles Stop bleeding by repairing holes in blood vessels Clean up the inside of blood vessels Removes temporary clot that stopped bleeding Sweeps off needless deposits that may cause blood flow blockages Two Major Diseases Linked to Hemostatic Abnormalities Bleeding = Hemorrhage Blood clot = Thrombosis Physiology of Hemostasis Wound Sealing break in vesselEFFRAC PRIMARY PLASMATIC HEMOSTASIS COAGULATION strong clot wound sealing blood FIBRINOLYSIS flow ± stopped clot destruction The Three Steps of Hemostasis Primary Hemostasis Interaction between vessel wall, platelets and adhesive proteins platelet clot Coagulation Consolidation -

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus: Successful Management of a Rare Presentation

Indian J Crit Care Med July-September 2008 Vol 12 Issue 3 Case Report Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and systemic lupus erythematosus: Successful management of a rare presentation Pratish George, Jasmine Das, Basant Pawar1, Naveen Kakkar2 Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) very rarely present simultaneously and pose a diagnostic and therapeutic dilemma to the critical care team. Prompt diagnosis and management with plasma exchange and immunosuppression is life-saving. A patient critically ill with TTP and SLE, successfully managed in the acute period of illness with plasma exchange, steroids and Abstract mycophenolate mofetil is described. Key words: Plasma exchange, systemic lupus erythematosus, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura Introduction Case Report Systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE) is diagnosed by A 30-year-old lady was admitted with fever and the presence of four or more of the following criteria, jaundice. A week earlier she had undergone an serially or simultaneously: malar rash, discoid rash, uncomplicated medical termination of pregnancy at photosensitivity, oral ulcers, non erosive arthritis, serositis, another hospital, at 13 weeks of gestation. She had an renal abnormalities including proteinuria or active urinary uneventful pregnancy with twins two years earlier and sediments, neuropsychiatric features, hematological the twins were diagnosed to have thalassemia major. abnormalities including hemolytic anemia, leucopenia, She was subsequently diagnosed to have thalassemia lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, immunological minor and her husband had thalassemia minor trait. No markers like anti-ds DNA or anti-Smith antibody and high earlier history of spontaneous Þ rst trimester abortions Antinuclear antibody titres. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic was present. purpura (TTP) in patients with SLE is extremely rare. -

Urticarial Vasculitis Associated with Essential Thrombocythaemia

Acta Derm Venereol 2014; 94: 244–245 SHORT COMMUNICATION Urticarial Vasculitis Associated with Essential Thrombocythaemia Annabel D. Scott, Nicholas Francis, Helen Yarranton and Sarita Singh Dermatology Registrar, Department of Dermatology, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, 369 Fulham Road, London SW10 9NH, United Kingdom. E-mail: [email protected] Accepted Apr 3, 2013; Epub ahead of print Aug 27, 2013 Urticarial vasculitis is a form of leucocytoclastic vas- prednisolone 30 mg once daily, which controlled her culitis whereby the skin lesions resemble urticaria. It is symptoms. associated with systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s A biopsy was taken from an uticarial lesion on the syndrome, hepatitis B and C viruses (1). Rarely it is asso- arm. Histology showed numerous perivascular neutro- ciated with an underlying haematological disorders and, phils and eosinophils with margination of neutrophils to the best of our knowledge, has never been reported in in the lumen of vessels and some leucocytoclasis with association with essential thrombocythaemia. We present red cell extravasation in keeping with an urticarial a case report of urticarial vasculitis associated with es- vasculitis (Fig. 2). sential thrombocythaemia. Blood tests revealed an erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 47 mm/h (normal range 1–12), a platelet count of 1,098 × 109/l (normal range 135–400) and an eosi- CASE REPORT nophilia of 1.0 × 109/l (normal range 0–0.2). Comple- A 32-year-old woman presented with a several month ment levels, thyroid function, serum iron, haemoglobin, history of recurrent urticaria without angioedema, 4 C-reactive protein, anti-nuclear antibody, anti-nuclear months post-partum. -

081999 Disseminated Intravascular Coagulation

The New England Journal of Medicine Current Concepts Systemic activation+ of coagulation DISSEMINATED INTRAVASCULAR COAGULATION Intravascular+ Depletion of platelets+ deposition of fibrin and coagulation factors MARCEL LEVI, M.D., AND HUGO TEN CATE, M.D. Thrombosis of small+ Bleeding and midsize vessels+ ISSEMINATED intravascular coagulation is and organ failure characterized by the widespread activation Dof coagulation, which results in the intravas- Figure 1. The Mechanism of Disseminated Intravascular Coag- cular formation of fibrin and ultimately thrombotic ulation. occlusion of small and midsize vessels.1-3 Intravascu- Systemic activation of coagulation leads to widespread intra- lar coagulation can also compromise the blood sup- vascular deposition of fibrin and depletion of platelets and co- agulation factors. As a result, thrombosis of small and midsize ply to organs and, in conjunction with hemodynam- vessels may occur, contributing to organ failure, and there may ic and metabolic derangements, may contribute to be severe bleeding. the failure of multiple organs. At the same time, the use and subsequent depletion of platelets and coag- ulation proteins resulting from the ongoing coagu- lation may induce severe bleeding (Fig. 1). Bleeding may be the presenting symptom in a patient with disseminated intravascular coagulation, a factor that can complicate decisions about treatment. TABLE 1. COMMON CLINICAL CONDITIONS ASSOCIATED WITH DISSEMINATED ASSOCIATED CLINICAL CONDITIONS INTRAVASCULAR COAGULATION. AND INCIDENCE Sepsis Infectious Disease Trauma Serious tissue injury Disseminated intravascular coagulation is an ac- Head injury Fat embolism quired disorder that occurs in a wide variety of clin- Cancer ical conditions, the most important of which are listed Myeloproliferative diseases in Table 1. -

What Everyone Should Know to Stop Bleeding After an Injury

What Everyone Should Know to Stop Bleeding After an Injury THE HARTFORD CONSENSUS The Joint Committee to Increase Survival from Active Shooter and Intentional Mass Casualty Events was convened by the American College of Surgeons in response to the growing number and severity of these events. The committee met in Hartford Connecticut and has produced a number of documents with rec- ommendations. The documents represent the consensus opinion of a multi-dis- ciplinary committee involving medical groups, the military, the National Security Council, Homeland Security, the FBI, law enforcement, fire rescue, and EMS. These recommendations have become known as the Hartford Consensus. The overarching principle of the Hartford Consensus is that no one should die from uncontrolled bleeding. The Hartford Consensus recommends that all citizens learn to stop bleeding. Further information about the Hartford Consensus and bleeding control can be found on the website: Bleedingcontrol.org 2 SAVE A LIFE: What Everyone Should Know to Stop Bleeding After an Injury Authors: Peter T. Pons, MD, FACEP Lenworth Jacobs, MD, MPH, FACS Acknowledgements: The authors acknowledge the contributions of Michael Cohen and James “Brooks” Hart, CMI to the design of this manual. Some images adapted from Adam Wehrle, EMT-P and NAEMT. © 2017 American College of Surgeons CONTENTS SECTION 1 3 ■ Introduction ■ Primary Principles of Trauma Care Response ■ The ABCs of Bleeding SECTION 2 5 ■ Ensure Your Own Safety SECTION 3 6 ■ A – Alert – call 9-1-1 SECTION 4 7 ■ B – Bleeding – find the bleeding injury SECTION 5 9 ■ C – Compress – apply pressure to stop the bleeding by: ■ Covering the wound with a clean cloth and applying pressure by pushing directly on it with both hands, OR ■Using a tourniquet, OR ■ Packing (stuff) the wound with gauze or a clean cloth and then applying pressure with both hands SECTION 6 13 ■ Summary 2 SECTION 1: INTRODUCTION Welcome to the Stop the Bleed: Bleeding Control for the Injured information booklet. -

Heart – Thrombus

Heart – Thrombus Figure Legend: Figure 1 Heart, Atrium - Thrombus in a male Swiss Webster mouse from a chronic study. A thrombus is present in the right atrium (arrow). Figure 2 Heart, Atrium - Thrombus in a male Swiss Webster mouse from a chronic study (higher magnification of Figure 1). Multiple layers of fibrin, erythrocytes, and scattered inflammatory cells (arrows) comprise this right atrial thrombus. Figure 3 Heart, Atrium - Thrombus in a male Swiss Webster mouse from a chronic study. A large thrombus with two foci of mineral fills the left atrium (arrow). Figure 4 Heart, Atrium - Thrombus in a male Swiss Webster mouse from a chronic study (higher magnification of Figure 3). This thrombus in the left atrium (arrows) has two dark, basophilic areas of mineral (arrowheads). 1 Heart – Thrombus Comment: Although thrombi can be seen in the right (Figure 1 and Figure 2) or left (Figure 3 and Figure 4) atrium, the most common site of spontaneously occurring and chemically induced thrombi is the left atrium. In acute situations, the lumen is distended by a mass of laminated fibrin layers, leukocytes, and red blood cells. In more chronic cases, there is more organization of the thrombus (e.g., presence of vascularized fibrous connective tissue, inflammation, and/or cartilage metaplasia), with potential attachment to the atrial wall. Spontaneous rates of cardiac thrombi were determined for control Fischer 344 rats and B6C3F1 mice: in 90-day studies, 0% in rats and mice; in 2-year studies, 0.7% in both genders of mice, 4% in male rats, and 1% in female rats. -

Immune-Pathophysiology and -Therapy of Childhood Purpura

Egypt J Pediatr Allergy Immunol 2009;7(1):3-13. Review article Immune-pathophysiology and -therapy of childhood purpura Safinaz A Elhabashy Professor of Pediatrics, Ain Shams University, Cairo Childhood purpura - Overview vasculitic disorders present with palpable Purpura (from the Latin, purpura, meaning purpura2. Purpura may be secondary to "purple") is the appearance of red or purple thrombocytopenia, platelet dysfunction, discolorations on the skin that do not blanch on coagulation factor deficiency or vascular defect as applying pressure. They are caused by bleeding shown in table 1. underneath the skin. Purpura measure 0.3-1cm, A thorough history (Table 2) and a careful while petechiae measure less than 3mm and physical examination (Table 3) are critical first ecchymoses greater than 1cm1. The integrity of steps in the evaluation of children with purpura3. the vascular system depends on three interacting When the history and physical examination elements: platelets, plasma coagulation factors suggest the presence of a bleeding disorder, and blood vessels. All three elements are required laboratory screening studies may include a for proper hemostasis, but the pattern of bleeding complete blood count, peripheral blood smear, depends to some extent on the specific defect. In prothrombin time (PT) and activated partial general, platelet disorders manifest petechiae, thromboplastin time (aPTT). With few exceptions, mucosal bleeding (wet purpura) or, rarely, central these studies should identify most hemostatic nervous system bleeding; -

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura

Thrombotic thrombocytopenic Purpura Flora Peyvandi Angelo Bianchi Bonomi Hemophilia and Thrombosis Center IRCCS Ca’ Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico University of Milan Milan, Italy Disclosures Research Support/P.I. No relevant conflicts of interest to declare Employee No relevant conflicts of interest to declare Consultant Kedrion, Octapharma Major Stockholder No relevant conflicts of interest to declare Speakers Bureau Shire, Alnylam Honoraria No relevant conflicts of interest to declare Scientific Advisory Ablynx, Shire, Roche Board Objectives • Advances in understanding the pathogenetic mechanisms and the resulting clinical implications in TTP • Which tests need to be done for diagnosis of congenital and acquired TTP • Standard and novel therapies for congenital and acquired TTP • Potential predictive markers of relapse and implications on patient management during remission Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP) First described in 1924 by Moschcowitz, TTP is a thrombotic microangiopathy characterized by: • Disseminated formation of platelet- rich thrombi in the microvasculature → Tissue ischemia with neurological, myocardial, renal signs & symptoms • Platelets consumption → Severe thrombocytopenia • Red blood cell fragmentation → Hemolytic anemia TTP epidemiology • Acute onset • Rare: 5-11 cases / million people / year • Two forms: congenital (<5%), acquired (>95%) • M:F ratio 1:3 • Peak of incidence: III-IV decades • Mortality reduced from 90% to 10-20% with appropriate therapy • Risk of recurrence: 30-35% Peyvandi et al, Haematologica 2010 TTP clinical features Bleeding 33 patients with ≥ 3 acute episodes + Thrombosis “Old” diagnostic pentad: • Microangiopathic hemolytic anemia • Thrombocytopenia • Fluctuating neurologic signs • Fever • Renal impairment ScullyLotta et et al, al, BJH BJH 20122010 TTP pathophysiology • Caused by ADAMTS13 deficiency (A Disintegrin And Metalloproteinase with ThromboSpondin type 1 motifs, member 13) • ADAMTS13 cleaves the VWF subunit at the Tyr1605–Met1606 peptide bond in the A2 domain Furlan M, et al. -

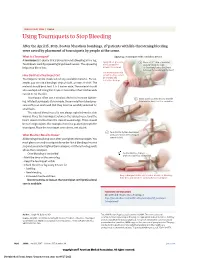

Using Tourniquets to Stop Bleeding

JAMA PATIENT PAGE | Trauma Using Tourniquets to Stop Bleeding After the April 15, 2013, Boston Marathon bombings, 27 patients with life-threatening bleeding were saved by placement of tourniquets by people at the scene. What Is a Tourniquet? Applying a tourniquet with a windlass device A tourniquet is a device that is placed around a bleeding arm or leg. Apply direct pressure 1 Place a 2-3” strip of material Tourniquets work by squeezing large blood vessels. The squeezing to the wound for about 2” from the edge helps stop blood loss. at least 15 minutes. of the wound over a long bone between the wound and the heart. Use a tourniquet only How Do I Put a Tourniquet On? when bleeding cannot be stopped and Tourniquets can be made out of any available material. For ex- is life threatening. ample, you can use a bandage, strip of cloth, or even a t-shirt. The material should be at least 2 to 3 inches wide. The material should also overlap itself. Using thin straps or material less than 2 inches wide can rip or cut the skin. Tourniquets often use a windlass device to increase tighten- 2 Insert a stick or other strong, straight ing. Inflated tourniquets (for example, those made from blood pres- item into the knot to act as a windlass. sure cuffs) can work well. But they must be carefully watched for small leaks. The injured blood vessel is not always right below the skin wound. Place the tourniquet between the injured vessel and the heart, about 2 inches from the closest wound edge. -

An Avoidable Cause of Thymoglobulin Anaphylaxis S

Brabant et al. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol (2017) 13:13 Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology DOI 10.1186/s13223-017-0186-9 CASE REPORT Open Access An avoidable cause of thymoglobulin anaphylaxis S. Brabant1*, A. Facon2, F. Provôt3, M. Labalette1, B. Wallaert4 and C. Chenivesse4 Abstract Background: Thymoglobulin® (anti-thymocyte globulin [rabbit]) is a purified pasteurised, gamma immune globulin obtained by immunisation of rabbits with human thymocytes. Anaphylactic allergic reactions to a first injection of thymoglobulin are rare. Case presentation: We report a case of serious anaphylactic reaction occurring after a first intraoperative injection of thymoglobulin during renal transplantation in a patient with undiagnosed respiratory allergy to rabbit allergens. Conclusions: This case report reinforces the importance of identifying rabbit allergy by a simple combination of clini- cal interview followed by confirmatory skin testing or blood tests of all patients prior to injection of thymoglobulin, which is formally contraindicated in patients with a history of hypersensitivity to rabbit proteins. Keywords: Thymoglobulin, Anaphylactic allergic reaction, Rabbit proteins Background [7]. Cases of serious anaphylactic reactions to thymo- Thymoglobulin is an IgG fraction purified from the globulin due to rabbit protein allergy are very rare, and serum of rabbits immunised against human thymocytes. consequently, specific tests for rabbit allergy are not The preparation consists of polyclonal antilymphocyte usually performed as part of the pre-transplant assess- IgG directed against T lymphocyte surface antigens, and ment. We report a case of serious anaphylactic reaction induction of profound lymphocyte depletion is though due to rabbit protein allergy following a first injection of to be the main mechanism of thymoglobulin-mediated thymoglobulin. -

Hypersensitivity Reactions (Types I, II, III, IV)

Hypersensitivity Reactions (Types I, II, III, IV) April 15, 2009 Inflammatory response - local, eliminates antigen without extensively damaging the host’s tissue. Hypersensitivity - immune & inflammatory responses that are harmful to the host (von Pirquet, 1906) - Type I Produce effector molecules Capable of ingesting foreign Particles Association with parasite infection Modified from Abbas, Lichtman & Pillai, Table 19-1 Type I hypersensitivity response IgE VH V L Cε1 CL Binds to mast cell Normal serum level = 0.0003 mg/ml Binds Fc region of IgE Link Intracellular signal trans. Initiation of degranulation Larche et al. Nat. Rev. Immunol 6:761-771, 2006 Abbas, Lichtman & Pillai,19-8 Factors in the development of allergic diseases • Geographical distribution • Environmental factors - climate, air pollution, socioeconomic status • Genetic risk factors • “Hygiene hypothesis” – Older siblings, day care – Exposure to certain foods, farm animals – Exposure to antibiotics during infancy • Cytokine milieu Adapted from Bach, JF. N Engl J Med 347:911, 2002. Upham & Holt. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol 5:167, 2005 Also: Papadopoulos and Kalobatsou. Curr Op Allergy Clin Immunol 7:91-95, 2007 IgE-mediated diseases in humans • Systemic (anaphylactic shock) •Asthma – Classification by immunopathological phenotype can be used to determine management strategies • Hay fever (allergic rhinitis) • Allergic conjunctivitis • Skin reactions • Food allergies Diseases in Humans (I) • Systemic anaphylaxis - potentially fatal - due to food ingestion (eggs, shellfish,