Books from Germany

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets. An analysis of authors, languages, and flows. Written by Miha Kovač and Rüdiger Wischenbart, with Jennifer Jursitzky and Sabine Kaldonek, and additional research by Julia Coufal. www.wischenbart.com/DiversityReport2010 Contact: [email protected] 2 Executive Summary The Diversity Report 2010, building on previous research presented in the respective reports of 2008 and 2009, surveys and analyzes 187 mostly European authors of contemporary fiction concerning translations of their works in 14 European languages and book markets. The goal of this study is to develop a more structured, data-based understanding of the patterns and driving forces of the translation markets across Europe. The key questions include the following: What characterizes the writers who succeed particularly well at being picked up by scouts, agents, and publishers for translation? Are patterns recognizable in the writers’ working biographies or their cultural background, the language in which a work is initially written, or the target languages most open for new voices? What forces shape a well-established literary career internationally? What channels and platforms are most helpful, or critical, for starting a path in translation? How do translations spread? The Diversity Report 2010 argues that translated books reflect a broad diversity of authors and styles, languages and career paths. We have confirmed, as a trend with great momentum, that the few authors and books at the very top, in terms of sales and recognition, expand their share of the overall reading markets with remarkable vigor. Not only are the real global stars to be counted on not very many fingers. -

Der Präsident

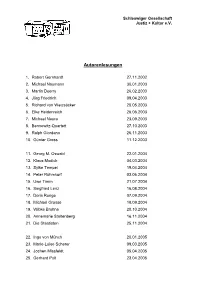

Schleswiger Gesellschaft Justiz + Kultur e.V. Autorenlesungen 1. Robert Gernhardt 27.11.2002 2. Michael Naumann 30.01.2003 3. Martin Doerry 26.02.2003 4. Jörg Friedrich 09.04.2003 5. Richard von Weizsäcker 20.05.2003 6. Elke Heidenreich 26.06.2003 7. Michael Naura 23.09.2003 8. Bennewitz-Quartett 27.10.2003 9. Ralph Giordano 26.11.2003 10. Günter Grass 11.12.2003 11. Georg M. Oswald 22.01.2004 12. Klaus Modick 04.03.2004 13. Sylke Tempel 19.04.2004 14. Peter Rühmkorf 03.06.2004 15. Uwe Timm 21.07.2004 16. Siegfried Lenz 16.08.2004 17. Doris Runge 07.09.2004 18. Michael Grosse 18.09.2004 19. Wibke Bruhns 20.10.2004 20. Annemarie Stoltenberg 16.11.2004 21. Die Staatisten 25.11.2004 22. Ingo von Münch 20.01.2005 23. Marie-Luise Scherer 09.03.2005 24. Jochen Missfeldt 05.04.2005 25. Gerhard Polt 23.04.2005 2 26. Walter Kempowski 25.08.2005 27. F.C. Delius 15.09.2005 28. Herbert Rosendorfer 31.10.2005 29. Annemarie Stoltenberg 23.11.2005 30. Klaus Bednarz 08.12.2005 31. Doris Gercke 26.01.2006 32. Günter Kunert 01.03.2006 33. Irene Dische 24.04.2006 34. Mozartabend (Michael Grosse, „Richtertrio“) ´ 11.05.2006 35. Roger Willemsen 12.06.2006 36. Gerd Fuchs 28.06.2006 37. Feridun Zaimoglu 07.09.2006 38. Matthias Wegner 11.10.2006 39. Annemarie Stoltenberg 15.11.2006 40. Ralf Rothmann 07.12.2006 41. Bettina Röhl 25.01.2007 42. -

Juergen Boos in Conversation with Jonathan Landgrebe the Ghost In

the frankfurt magazine Juergen Boos in Conversation with Jonathan Landgrebe The Ghost in the Machine – Artificial Intelligence in German Books The Bauhaus in the World – A Century of Inspiration Time for a Second Look – Graphic Adaptations of Multimedia Worlds EDITORIAL Dear readers, Bauhaus. And they’re not just for display: anyone Are you intrigued by our cover photo? I’d like to can try the costumes on. Their first appearance is tell you the story behind this image. In 2019, we’re at the German Guest of Honour presentation at Cicek © FBM/Nurettin celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Bau the Taipei International Book Exhibition in Febru haus – the most important art, design and archi ary. And of course, this isn’t all we’re presenting in Bärbel Becker tecture school of the 20th century. On our cover, Taipei: we’ve put together a special collection of has been at the Frank you see three costumes based on the original new books about the Bauhaus movement which furter Buchmesse drawings and colour swatches of Oskar Schlem is also on display. This magazine will give you an for many years and is mer, the painter and sculptor who created the Tri insight into our Bauhaus showcase as well. the director of the adic Ballet – a modernist dance concept. From This is the second issue of the frankfurt magazine. International Projects 1920, Schlemmer led Bauhaus workshops in paint We received lots of positive feedback from the department. ing murals, and in wood and stone sculpture, and readers of our first issue – publishing colleagues, from 1923–1929, the Bauhaus theatre. -

PEN / IRL Report on the International Situation of Literary Translation

to bE tRaNs- LatEd oR Not to bE PEN / IRL REPoRt oN thE INtERNatIoNaL sItuatIoN of LItERaRy tRaNsLatIoN Esther Allen (ed.) To be Trans- laTed or noT To be First published: September 2007 © Institut Ramon Llull, 2007 Diputació, 279 E-08007 Barcelona www.llull.cat [email protected] Texts: Gabriela Adamo, Esther Allen, Carme Arenas, Paul Auster, Narcís Comadira, Chen Maiping, Bas Pauw, Anne-Sophie Simenel, Simona Škrabec, Riky Stock, Ngu~gı~ wa Thiong’o. Translations from Catalan: Deborah Bonner, Ita Roberts, Andrew Spence, Sarah Yandell Coordination and edition of the report: Humanities and Science Department, Institut Ramon Llull Design: Laura Estragués Editorial coordination: Critèria sccl. Printed by: Gramagraf, sccl ISBN: 84-96767-63-9 DL: B-45548-2007 Printed in Spain CONTENTS 7 Foreword, by Paul Auster 9 Presentations Translation and Linguistic Rights, by Jirˇí Gruša (International PEN) Participating in the Translation Debate, by Josep Bargalló (Institut Ramon Llull) 13 Introduction, by Esther Allen and Carles Torner 17 1. Translation, Globalization and English, by Esther Allen 1.1 English as an Invasive Species 1.2 World Literature and English 35 2. Literary Translation: The International Panorama, by Simona Škrabec and PEN centers from twelve countries 2.1 Projection Abroad 2.2 Acceptance of Translated Literature 49 3. Six Case Studies on Literary Translation 3.1 The Netherlands, by Bas Pauw 3.2 Argentina, by Gabriela Adamo 3.3 Catalonia, by Carme Arenas and Simona Škrabec 3.4 Germany, by Riky Stock 3.5 China, by Chen Maiping 3.6 France, by Anne-Sophie Simenel 93 4. Experiences in Literary Translation, by Esther Allen and Simona Škrabec 4.1 Experiences in the United States 4.2 Experiences in four European Countries 117 5. -

The Novel in German Since 1990 Edited by Stuart Taberner Excerpt More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19237-8 - The Novel in German Since 1990 Edited by Stuart Taberner Excerpt More information Introduction: The novel in German since 1990 Stuart Taberner the problem with the german novel In his The German Novel, published in 1956 and for a long time a standard reference work in the English-speaking world, Roy Pascal averred that even the very best of German fiction was marred by a ‘sad lack of the energy and bite of passion’. It was impossible to deny, the British critic claimed, that there was ‘something provincial, philistine’ at its core. Indeed, he concluded, German writing was strangely lacking – ‘Altogether the char- acters in the German novels seem less alive, less avid of life, less capable of overflowing exuberances, than those of the great European novels.’1 Pascal’s oddly damning assessment of his object of study might today be merely of historical interest as an example of the supposition of a German Sonderweg (special path) apart from other European nations, widely promulgated in the countries that had defeated Nazism only a few years earlier, if it were not for the fact that similar indictments feature throughout the 1990s in a series of debates on the German novel’s post- war development. These more recent criticisms, however, were voiced not by critics outside Germany seeking to identify its ‘peculiarity’ but in the Federal Republic itself. While scholarly attention has focused, then, on Ulrich Greiner’s attack on Christa Wolf’s alleged cowardly opportunism in waiting until the collapse -

Chicago Chicago Fall 2015

UNIV ERSIT Y O F CH ICAGO PRESS 1427 EAST 60TH STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60637 KS OO B LL FA CHICAGO 2015 CHICAGO FALL 2015 FALL Recently Published Fall 2015 Contents General Interest 1 Special Interest 50 Paperbacks 118 Blood Runs Green Invisible Distributed Books 145 The Murder That Transfixed Gilded The Dangerous Allure of the Unseen Age Chicago Philip Ball Gillian O’Brien ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23889-0 Author Index 412 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24895-0 Cloth $27.50/£19.50 Cloth $25.00/£17.50 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23892-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24900-1 COBE/EU Title Index 414 Subject Index 416 Ordering Inside Information back cover Infested Elephant Don How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse Bedrooms and Took Over the World Caitlin O’Connell Brooke Borel ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10611-3 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04193-3 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10625-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04209-1 Plankton Say No to the Devil Cover illustration: Lauren Nassef Wonders of the Drifting World The Life and Musical Genius of Cover design by Mary Shanahan Christian Sardet Rev. Gary Davis Catalog design by Alice Reimann and Mary Shanahan ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18871-3 Ian Zack Cloth $45.00/£31.50 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23410-6 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-26534-6 Cloth $30.00/£21.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23424-3 JESSA CRISPIN The Dead Ladies Project Exiles, Expats, and Ex-Countries hen Jessa Crispin was thirty, she burned her settled Chica- go life to the ground and took off for Berlin with a pair of W suitcases and no plan beyond leaving. -

German Studies Association Newsletter ______

______________________________________________________________________________ German Studies Association Newsletter __________________________________________________________________ Volume XLII Number 1 Spring 2017 2 German Studies Association Newsletter Volume XLII Number 1 Spring 2017 __________________________________________________________________________ Table of Contents Letter from the President ................................................................................................................ 3 Letter from the Executive Director ................................................................................................. 6 Conference Details .......................................................................................................................... 9 Conference Highlights .................................................................................................................. 11 A List of Dissertations in German Studies, 2015-2017 ................................................................ 14 Statement of the German Studies Association on the Admission and Vetting of Non-Citizens to the United States, January 2017 .................................................................................................... 26 Announcements............................................................................................................................. 27 Austrian Cultural Forum New York: Young Scholars GSA Travel Grants 2017 .................... 27 Berlin Program for Advanced German -

Autumn 2014 Foreign Rights

FOREIGN RIGHTS AUTU M N 2014 REPRESENTATIVES China (mainland) Hercules Business & Culture GmbH, Niederdorfelden phone: +49-6101-407921, fax: +49-6101-407922 e-mail: [email protected] Hungary Balla-Sztojkov Literary Agency, Budapest phone: +36-1-456 03 11, fax: +36-1-215 44 20 e-mail: [email protected] Israel The Deborah Harris Agency, Jerusalem phone: +972-2-5633237, fax: +972-2-5618711 e-mail: [email protected] Italy Marco Vigevani, Agenzia Letteraria, Milano phone: +39-02-86 99 65 53, fax: +39-02-86 98 23 09 e-mail: [email protected] Japan Meike Marx Literary Agency, Hokkaido phone: +81-164-25 1466, fax: +81-164-26 38 44 e-mail: [email protected] Korea MOMO Agency, Seoul phone: +82-2-337-8606, fax: +82-2-337-8702 e-mail: [email protected] Netherlands LiTrans, Tino Köhler, Amsterdam phone: +31-20- 685 53 80, fax: +31-20- 685 53 80 e-mail: [email protected] Poland Graal Literary Agency, Warszawa phone: +48-22-895 2000, fax: +48-22-895 2001 e-mail: [email protected] Romania Simona Kessler, International Copyright Ageny, Ltd., Bucharest phone: +402-2-231 81 50, fax: +402-2-231 45 22 e-mail: [email protected] Scandinavia Leonhardt & Høier Literary Agency aps, Kopenhagen phone: +45-33 13 25 23, fax: +45-33 13 49 92 e-mail: [email protected] Spain, Portugal A.C.E.R., Agencia Literaria, Madrid and Latin America phone: +34-91-369 2061, fax: +34-91-369 2052 e-mail: [email protected] Stock/Corbis Umschlagmotiv: © Kirn Vintage Foreign Rights Service translated by Ruth Feuchtwanger, -

Heinrich Detering Verleiht Den Kleist-Preis 2015 an Monika Rinck

Universität zu Köln T: 0221 470-1292 (Sekr.) Internationales Kolleg T: 0170-3151010 (priv.) Morphomata (BMBF) [email protected] Albertus-Magnus-Platz 50923 Köln, Deutschland www.heinrich-von-kleist.org DER PRÄSIDENT Prof. Dr. Günter Blamberger Köln, 30.4.2015 PRESSEMITTEILUNG KLEIST-PREIS 2015 Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren, darf ich Sie bitten, folgende Meldung zu verbreiten: Heinrich Detering verleiht den Kleist-Preis 2015 an Monika Rinck Der Kleist-Preis des Jahres 2015 geht an die Berliner Autorin Monika Rinck. Bekannt geworden ist sie durch Lyrik, Prosa und Essays, durch interdisziplinäre wie intermediale Grenzüberschreitungen, die sie als Meisterin aller Tonlagen zeigen. Rincks Registerreichtum ist so stupend wie ihr Witz. Ihre Texte können alles zugleich sein: virtuos und gelehrsam, berührend und pointenreich, humorvoll und melancholisch. Bekannt geworden ist sie durch Lyrikbände wie „zum fernbleiben der umarmung“ (2007), „Helle Verwirrung“ (2009) und „Honigprotokolle“ (2012). Im März 2015 erschien ihre Essaysammlung „Risiko und Idiotie. Streitschriften“, wiederum bei Kookbooks in Berlin. Monika Rincks Werk wurde mehrfach bereits ausgezeichnet, u.a. mit dem Ernst-Meister-Preis 2008, dem Georg-K.- Glaser-Preis 2010, dem Berliner Kunstpreis-Literatur 2012 und dem Peter-Huchel-Preis 2013. Der Kleist-Preis wird Monika Rinck am 22. November 2015 in Berlin während einer Matinée im Berliner Ensemble übergeben, die Claus Peymann inszenieren wird. Die Laudatio hält Heinrich Detering, der Präsident der Deutschen Akademie für -

Social & Behavioural Sciences 9Th ICEEPSY 2018 International

The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS Future Academy ISSN: 2357-1330 https://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.41 9th ICEEPSY 2018 International Conference on Education & Educational Psychology LEARNING HISTORY THROUGH STORIES ABOUT EAST GERMANY Nadezda Heinrichova (a)* *Corresponding author (a) University of Hradec Kralove, Faculty of Education, Rokitanskeho 62, 50003 Hradec Kralove, Czech Republic, [email protected] Abstract The article presents the results in which university students – majoring in teaching German as FL – expressed their ability, viewpoint and experience with using contemporary German literature to understand the life in East Germany as a part of history of the 20st century. The research was carried out in the winter term 2016 and 2017 on the basis of the following books, all awarded / nominated for the German Book Prize: Eugen Ruge’s (2011) In Zeiten des abnehmenden Lichts (In Times of Fading Light); Lutz Seiler’s (2014) Kruso; Uwe Tellkamp’s (2008) Der Turm (The Tower) and Angelika Klüssendorf’s (2011) Das Mädchen (The Girl). The aim of my literary course was, firstly, to provide the skills to read literature as a resource for understanding life and historical change, how other people experience emotional issues, and secondly, to give students an outline of the life in East Germany, to see the parallels with other countries in the Eastern Bloc and to stimulate students’ interest in the history of other countries in the Eastern Bloc. Thirdly, the aim was to use the texts as a stimulus to practice writing and speaking in discussions. Last but not least, to present how a teacher can enrich the foreign language lessons with literary text because the future teachers should not neglect the possibility of using literature in FLT. -

Verzeichnis Der Veröffentlichungen Und Lehrveranstaltungen

Prof. Dr. Gunther Nickel Verzeichnis der Veröffentlichungen und Lehrveranstaltungen Gliederung a) Bücher b) Ausstellungen und Ausstellungskataloge c) Herausgegebene Reihen d) Unselbständige Veröffentlichungen e) Beiträge in Lexika f) Rezensionen und Feuilletons g) Konzeption und Organisation von Tagungen h) Tätigkeit als Beirat, als Juror, in Arbeitsgemeinschaften i) Lehrveranstaltungen j) Betreute Dissertation a) Bücher 1. [Zusammen mit Bärbel Boldt u.a. (Hg.):] Carl von Ossietzky, Ein Lesebuch . Reinbek: Rowohlt 1989. 255 S. 2. [Als Mitherausgeber der Bände 5, 6 und 8:] Carl von Ossietzky, Sämtliche Werke in acht Bänden. Oldenburger Ausgabe , hg. von Werner Boldt, Dirk Grathoff, Gerhard Kraiker und Elke Suhr. Reinbek: Rowohlt 1994. 753 S.; 631 S.; 586 S. 3. Die Schaubühne / Die Weltbühne. Siegfried Jacobsohns Wochenschrift und ihr ästhetisches Programm . Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag 1996. 272 S. 4. [Zusammen mit Luise Dirscherl (Hg.):] Der blaue Engel. Die Drehbuchentwürfe , mit einer Chronik zur Entstehung des Films von Werner Sudendorf. St. Ingbert: Röhrig Universi- tätsverlag 2000. 517 S. 5. [Zusammen mit Johanna Schrön (Hg.):] Carl Zuckmayer, Geheimreport. Göttingen: Wall- stein 2002. 528 S. Eine Taschenbuchausgabe ist 2004 im Deutschen Taschenbuchverlag (dtv) erschienen. 6. [Als Herausgeber:] Carl Zuckmayer / Annemarie Seidel, Briefwechsel . Göttingen: Wallstein 2003. 328 S. Eine Taschenbuchausgabe ist 2008 im Fischer Taschenbuchverlag erschie- nen. 7. [Zusammen mit Johanna Schrön und Hans Wagener (Hg.):] Carl Zuckmayer, Deutsch- landbericht für das Kriegsministerium der Vereinigten Staaten von Amerika (1947) . Göttingen: Wallstein 2004. 307 S. Eine Taschenbuchausgabe ist 2007 im Fischer Taschenbuchverlag erschienen. 8. [Zusammen mit Alexander Weigel, in Zusammenarbeit mit Hanne Knickmann und Johanna Schrön (Hg.):] Siegfried Jacobsohn, Gesammelte Schriften , 5 Bde. Göttingen: Wall- stein 2005 (Veröffentlichung der Deutschen Akademie für Sprache und Dichtung; 85). -

Residenz Verlag Non-Fiction Foreign Rights 2008

Residenz Verlag ▪ Non-Fiction ▪ Foreign Rights ▪ 2018 www.residenzverlag.at New Titles – Autumn 2018 Raimund Löw/Kerstin Witt-Löw: Global Power China Hartmut Rosa: 2018, 256 pages, Hardcover, ISBN 9783701734528 More World! Outlines of a Critique of Availability Never in human history has life changed so 2018, 96 pages, Sofcover, ISBN 9783701734467 dramatically in such a short time for so many Modernity’s core people as it has in China endeavour is to increase over the past 30 years. our personal reach, our Under the command of grasp on the world. state president and party However, according to leader Xi Jinping, China is Hartmut Rosa’s storming its way into the controversial theory, this top tier of global powers. available world is a silent Raimund Löw and one. There is no longer a Kerstin Witt-Löw have dialogue with it. Rosa first-hand experience of counters this progressive the material rise of the Chinese middle classes and the estrangement between country’s strict boundaries specified through human and world with censorship and political patronization. Raimund Löw what he refers to as “resonance”: a reverberating, has also reported from Peking and Hong Kong for the unquantifiable relationship with an unavailable Austrian Broadcasting Corporation ORF. What world. Resonance develops when we engage with remains of Mao? How does Peking intend to deal with something unknown, something irritating, the smog and the poisoning of the environment? How something that lies beyond our controlling reach. The does China view its role in the world? These are some outcome of this process can’t be planned or predicted, of the issues discussed in this analytical reportage on thus a moment of unavailability is always inherent to the 21st century’s greatest emerging superpower.