The Novel in German Since 1990 Edited by Stuart Taberner Excerpt More Information

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Zeitschrift Für Germanistik

Zeitschrift für Germanistik Neue Folge XXVI – 3/2016 Herausgeberkollegium Steffen Martus (Geschäftsführender Herausgeber, Berlin) Alexander Košenina (Hannover) Erhard Schütz (Berlin) Ulrike Vedder (Berlin) Gastherausgeberin Katja Stopka (Leipzig) Sonderdruck PETER LANG Internationaler Verlag der Wissenschaften Bern · Berlin · Bruxelles · Frankfurt am Main · New York · Oxford · Wien Inhaltsverzeichnis Schwerpunkt: Neue Materialien Literarische Schreibprozesse am Beispiel der Geschich - te des Instituts für Literatur „Johannes R. Becher“ ISABELLE LEHN – „Wo das Glück sicher wohnt.“ (IfL) / Deutsches Literaturinstitut Leipzig (DLL) Politische Kontrolle und Zensur am Institut für Literatur „Johannes R. Becher“ 622 ISABELLE LEHN, SASCHA MACHT, KATJA STOP- KA – Das Institut für Literatur „Johannes R. Becher“. Eine Institution im Wandel von vier Dossiers Dekaden DDR-Literaturgeschichte. Vorwort 485 ICOLA AmiNSki KATJA STOPKA – Rechenschaftsberichte und Se- N K – Andreas Gryphius (1616– mi narprotokolle, biographische Erzählungen 1664). Zum 400. Geburtstag des „Unsterb- und Zeitzeugenberichte. Eine Kritik zur Quel- lichen“ 634 lenlage des Instituts für Literatur „Johannes PHILIPP BÖTTCHER – „Der Herold des deutschen R. Becher“ 502 Bürgerthums“. Zum 200. Geburtstag Gustav Freytags (1816–1895) 638 ISABELLE LEHN – „Von der Lehrbarkeit der litera- rischen Meisterschaft“. Literarische Nachwuchs- STEPHAN BRAESE – „Ich bin bei weitem der kon- förderung und Begabtenpolitik am Institut für ventionellste Schriftsteller, den ich lesen kann“. Literatur „Johannes R. Becher“ 514 Zum 100. Geburtstag von Wolfgang Hildeshei- mer (1916–1991) 646 HANS-ULRICH TREICHEL – Ein Wort, geflissent- lich gemieden. Dekadenz und Formalismus am Institut für Literatur „Johannes R. Becher“ 530 Konferenzberichte MAJA-MARIA BECKER – „Was hat das mit sozia- listischer Lyrik zu tun?“. Die Bedeutung der Die Präsentation kanonischer Werke um 1900. Se - Lyrik am Institut für Literatur „Johannes R. -

Come Usare Il Libro

Come usare il libro Il libro è diviso in 14 moduli dalle origini ai nostri giorni. La pagina cronologica di apertura di ciascun modulo mostra gli eventi significativi della Storia e della Letteratura trattati riportandoli su una linea temporale di riferimento. L’icona rossa rimanda alla sezione Geschichte und Literatur del CD-ROM (vedi pagina 5). Nelle pagine di contesto storico Geschichtliches Bild, di contesto socio-culturale Leute und Gesellschaft e di contesto letterario Literarische Landschaft che aprono ogni modulo troverete un glossario evidenziato in azzurro con le parole chiave per comprendere il contenuto del testo e facilitarvi nella lettura. Vi sarà utile impararle a memoria. Incontrerete certamente anche parole nuove che dovrete cercare sul dizionario; prima di farlo però cercate di intuirne il significato dal contesto. Ogni contesto termina con Nach dem Lesen, ovvero I contesti storico, esercizi per fissare ciò che socio-culturale e letterario si è appena letto. Per ogni possono presentare dei brevi testo presentato il consiglio box di approfondimento è di leggere e ripetere ad e curiosità riguardanti alta voce. Per aiutarvi a principalmente fatti storici memorizzare meglio le e culturali (in azzurro) parole e a familiarizzare o trasposizioni con la lingua tedesca avete cinematografiche di a disposizione la sezione opere letterarie (in rosso). Geschichte und Literatur del CD-ROM che accompagna il volume. 3 3415_Medaglia 00.indd 3 29-02-2012 15:42:38 Come usare il libro La sezione Autori è caratterizzata dal colore rosso ed è strutturata in tre parti. Nella prima parte viene presentato l’autore: breve biografia accompagnata dalla cronologia di alcune delle sue opere più importanti e commento generale alla sua opera, con breve trattazione critica del brano di lettura proposto. -

Fall 2011 / Winter 2012 Dalkey Archive Press

FALL 2011 / WINTER 2012 DALKEY ARCHIVE PRESS CHAMPAIGN - LONDON - DUBLIN RECIPIENT OF THE 2010 SANDROF LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT Award FROM THE NatiONAL BOOK CRITICS CIRCLE what’s inside . 5 The Truth about Marie, Jean-Philippe Toussaint 6 The Splendor of Portugal, António Lobo Antunes 7 Barley Patch, Gerald Murnane 8 The Faster I Walk, the Smaller I Am, Kjersti A. Skomsvold 9 The No World Concerto, A. G. Porta 10 Dukla, Andrzej Stasiuk 11 Joseph Walser’s Machine, Gonçalo M. Tavares Perfect Lives, Robert Ashley (New Foreword by Kyle Gann) 12 Best European Fiction 2012, Aleksandar Hemon, series ed. (Preface by Nicole Krauss) 13 Isle of the Dead, Gerhard Meier (Afterword by Burton Pike) 14 Minuet for Guitar, Vitomil Zupan The Galley Slave, Drago Jančar 15 Invitation to a Voyage, François Emmanuel Assisted Living, Nikanor Teratologen (Afterword by Stig Sæterbakken) 16 The Recognitions, William Gaddis (Introduction by William H. Gass) J R, William Gaddis (New Introduction by Robert Coover) 17 Fire the Bastards!, Jack Green 18 The Book of Emotions, João Almino 19 Mathématique:, Jacques Roubaud 20 Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, Aglaja Veteranyi (Afterword by Vincent Kling) 21 Iranian Writers Uncensored: Freedom, Democracy, and the Word in Contemporary Iran, Shiva Rahbaran Critical Dictionary of Mexican Literature (1955–2010), Christopher Domínguez Michael 22 Autoportrait, Edouard Levé 23 4:56: Poems, Carlos Fuentes Lemus (Afterword by Juan Goytisolo) 24 The Review of Contemporary Fiction: The Failure Issue, Joshua Cohen, guest ed. Available Again 25 The Family of Pascual Duarte, Camilo José Cela 26 On Elegance While Sleeping, Viscount Lascano Tegui 27 The Other City, Michal Ajvaz National Literature Series 28 Hebrew Literature Series 29 Slovenian Literature Series 30 Distribution and Sales Contact Information JEAN-PHILIPPE TOUSSAINT titles available from Dalkey Archive Press “Right now I am teaching my students a book called The Bathroom by the Belgian experimentalist Jean-Philippe Toussaint—at least I used to think he was an experimentalist. -

Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann

Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature Volume 28 Issue 1 Writing and Reading Berlin Article 10 1-1-2004 Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann Anke Biendarra University of Cincinnati Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl Part of the German Literature Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Biendarra, Anke (2004) "Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann," Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: Vol. 28: Iss. 1, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.4148/2334-4415.1574 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann Abstract In March 1999, critic Volker Hage adopted a term in Der Spiegel that subsequently dominated public discussions about new German literature by female authors-"Fräuleinwunder"… Keywords 1999, Volker Hage, Der Spiegel, new German literature, female authors, Fräuleinwunder, Julia Franck, Judith Hermann, critic, gender, generation This article is available in Studies in 20th & 21st Century Literature: https://newprairiepress.org/sttcl/vol28/iss1/10 Biendarra: Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann Gen(d)eration Next: Prose by Julia Franck and Judith Hermann Anke S. Biendarra University of Cincinnati In March 1999, critic Volker Hage adopted a term in Der Spiegel that subsequently dominated public discussions about new Ger- man literature by female authors-"Frauleinwunder."' He uses it collectively for "the young women who make sure that German literature is again a subject of discussion this spring." Hage as- serts that they seem less concerned with "the German question," the consequences of two German dictatorships, and prefer in- stead to thematize "eroticism and love" in their texts. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Bernd Fischer December 2016 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Professor of German, Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, OSU, 1995-present Chairperson, Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, OSU, 1996-2008; Interim Chairperson 2012-14 Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellowship, Universität Bonn, Summer/Autumn 2016 Principal Investigator, “Lesen Germanisten anders? Zur kritischen Kompetenz von Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft,“ Four-day section of the XIII. Kongress der Internationalen Vereinigung für Germanitik, Shanghai, China, 23-30 Aug. 2015 International Workshop, “The Political Kleist,” OSU, 3 April 2014 International Conference, “Transformations of the Public Sphere,” Mershon Center, OSU, 13-14 Apr. 2012 (with May Mergenthaler) International Conference “Literature and the Public Sphere: The Case of Heinrich von Kleist,” Humanities Institute, OSU, 21-22 Sept. 2011 International Conference (Humboldt Kolleg) “Kleist and Modernity,” University of Otago, New Zealand, 24-27 Sep. 2010 (with Tim Mehigan) Principal Investigator, “The Public Sphere and Modern Social Imaginaries,” working group at the Institute for Collaborative Research and Public Humanities, OSU, 2009-2011 Board Member, Melton Center for Jewish Studies, 2009- Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellowship, Universität Essen, Summer 2005 Visiting Professor, Universität Essen (intensive six-week seminar), Spring 2005 Editor, The German Quarterly, published by the American Association of Teachers of German, 1997-1999 (with Dagmar Lorenz) Executive -

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets

Diversity Report 2010 1 Diversity Report 2010 Literary Translation in Current European Book Markets. An analysis of authors, languages, and flows. Written by Miha Kovač and Rüdiger Wischenbart, with Jennifer Jursitzky and Sabine Kaldonek, and additional research by Julia Coufal. www.wischenbart.com/DiversityReport2010 Contact: [email protected] 2 Executive Summary The Diversity Report 2010, building on previous research presented in the respective reports of 2008 and 2009, surveys and analyzes 187 mostly European authors of contemporary fiction concerning translations of their works in 14 European languages and book markets. The goal of this study is to develop a more structured, data-based understanding of the patterns and driving forces of the translation markets across Europe. The key questions include the following: What characterizes the writers who succeed particularly well at being picked up by scouts, agents, and publishers for translation? Are patterns recognizable in the writers’ working biographies or their cultural background, the language in which a work is initially written, or the target languages most open for new voices? What forces shape a well-established literary career internationally? What channels and platforms are most helpful, or critical, for starting a path in translation? How do translations spread? The Diversity Report 2010 argues that translated books reflect a broad diversity of authors and styles, languages and career paths. We have confirmed, as a trend with great momentum, that the few authors and books at the very top, in terms of sales and recognition, expand their share of the overall reading markets with remarkable vigor. Not only are the real global stars to be counted on not very many fingers. -

Załącznik Nr 1A

Załącznik nr 1 do Uchwały Senatu Nr XXV-9.48/21 z dnia 30 czerwca 2021 r. Zagadnienia do egzaminu dyplomowego dla studentów kierunku germanistyka studia stacjonarne pierwszego stopnia kończących studia od roku akademickiego 2021/2022 1/ z dyscypliny językoznawstwo: 1: Sprache und Linguistik 1.1. Das Wesen der Sprache 1.1.1. Sprache als soziales Phänomen 1.1.2. Sprache als historisches Phänomen 1.1.3. Sprache als biologisches Phänomen 1.1.4. Sprache als kognitives Phänomen 1.2. Funktionen von Sprache 1.3. Erscheinungsformen von Sprache 1.4. Beschreibungsmöglichkeiten von Sprache 2: Semiotik 2.1. Zeichentypen 2.2. Sprachliches Zeichen 2.3. Zeichen und Zeichenbenutzer 3: Phonetik und Phonologie 3.1. Artikulationbasis 3.2. das Phonemsystem 4: Morphologie und Wortbildung 4.1. Morphologische Grundbegriffe 4.2. Wortarten 4.3. Flexion 4.3.1 grammatische Kategorien 4.4. Wortbildung 4.4.1. Wortstruktur 4.4.2. Wortbildungstypen 5: Syntax 5.1. Grundbegriffe 5.2. Kategorien und Funktionen 5.3. Topologische Felder 5.4. Satzarten 5.5. Konstituentenstruktur 6: Semantik und Lexikologie 6.1. semantische Grundbegriffe 6.2. Wortsemantik 6.3. Satzsemantik 6.4. Textsemantik 6.5. Wortfamilien, Wortfelder 6.6. Bedeutungsbeziehungen 7: Textlinguistik 7.1. Grundbegriffe 7.2. Textmerkmale 7.3. Textfunktionen 7.4. Textsorten 7.5. Textkonstitution (graphische, syntaktische, semantische, pragmatische) 8: Pragmatik 8.1. Deixis und Anapher 8.2. Implikaturen 8.3. Präsupposition 8.4. Sprechakte 8.5. Gesprächlinguistik 9: Psycholinguistik 9.1. Sprachperzeption 9.2. Sprachproduktion 9.3. Spracherwerb 10. Soziolinguistik 10.1. soziolinguistische Begriffe 10.2 Gemeinsprache 10.3. Fachsprache 10.4. Sondersprache 10.5. -

Der Präsident

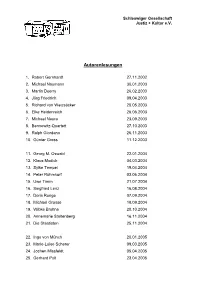

Schleswiger Gesellschaft Justiz + Kultur e.V. Autorenlesungen 1. Robert Gernhardt 27.11.2002 2. Michael Naumann 30.01.2003 3. Martin Doerry 26.02.2003 4. Jörg Friedrich 09.04.2003 5. Richard von Weizsäcker 20.05.2003 6. Elke Heidenreich 26.06.2003 7. Michael Naura 23.09.2003 8. Bennewitz-Quartett 27.10.2003 9. Ralph Giordano 26.11.2003 10. Günter Grass 11.12.2003 11. Georg M. Oswald 22.01.2004 12. Klaus Modick 04.03.2004 13. Sylke Tempel 19.04.2004 14. Peter Rühmkorf 03.06.2004 15. Uwe Timm 21.07.2004 16. Siegfried Lenz 16.08.2004 17. Doris Runge 07.09.2004 18. Michael Grosse 18.09.2004 19. Wibke Bruhns 20.10.2004 20. Annemarie Stoltenberg 16.11.2004 21. Die Staatisten 25.11.2004 22. Ingo von Münch 20.01.2005 23. Marie-Luise Scherer 09.03.2005 24. Jochen Missfeldt 05.04.2005 25. Gerhard Polt 23.04.2005 2 26. Walter Kempowski 25.08.2005 27. F.C. Delius 15.09.2005 28. Herbert Rosendorfer 31.10.2005 29. Annemarie Stoltenberg 23.11.2005 30. Klaus Bednarz 08.12.2005 31. Doris Gercke 26.01.2006 32. Günter Kunert 01.03.2006 33. Irene Dische 24.04.2006 34. Mozartabend (Michael Grosse, „Richtertrio“) ´ 11.05.2006 35. Roger Willemsen 12.06.2006 36. Gerd Fuchs 28.06.2006 37. Feridun Zaimoglu 07.09.2006 38. Matthias Wegner 11.10.2006 39. Annemarie Stoltenberg 15.11.2006 40. Ralf Rothmann 07.12.2006 41. Bettina Röhl 25.01.2007 42. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Bernd Fischer January 2020 PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE Professor of German, Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, OSU, 1995-present Chairperson, Department of Germanic Languages and Literatures, OSU, 1996-2008; Interim Chairperson 2012-14 Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellowship, Universität Bonn, Summer/Autumn 2016 Principal Investigator, “Lesen Germanisten anders? Zur kritischen Kompetenz von Literatur- und Kulturwissenschaft,“ Four-day session of the XIII. Kongress der Internationalen Vereinigung für Germanitik, Shanghai, China, 23-30 Aug. 2015 International Workshop, “The Political Kleist,” OSU, 3 April 2014 International Conference, “Transformations of the Public Sphere,” Mershon Center, OSU, 13-14 Apr. 2012 (with May Mergenthaler) International Conference “Literature and the Public Sphere: The Case of Heinrich von Kleist,” Humanities Institute, OSU, 21-22 Sept. 2011 International Conference (Humboldt Kolleg) “Kleist and Modernity,” University of Otago, New Zealand, 24-27 Sep. 2010 (with Tim Mehigan) Principal Investigator, “The Public Sphere and Modern Social Imaginaries,” working group at the Institute for Collaborative Research and Public Humanities, OSU, 2009-2011 Board Member, Melton Center for Jewish Studies, 2009- Alexander von Humboldt Research Fellowship, Universität Essen, Summer 2005 Visiting Professor, Universität Essen (intensive six-week seminar), Spring 2005 Editor, The German Quarterly, published by the American Association of Teachers of German, 1997-1999 (with Dagmar Lorenz) Executive -

PEN / IRL Report on the International Situation of Literary Translation

to bE tRaNs- LatEd oR Not to bE PEN / IRL REPoRt oN thE INtERNatIoNaL sItuatIoN of LItERaRy tRaNsLatIoN Esther Allen (ed.) To be Trans- laTed or noT To be First published: September 2007 © Institut Ramon Llull, 2007 Diputació, 279 E-08007 Barcelona www.llull.cat [email protected] Texts: Gabriela Adamo, Esther Allen, Carme Arenas, Paul Auster, Narcís Comadira, Chen Maiping, Bas Pauw, Anne-Sophie Simenel, Simona Škrabec, Riky Stock, Ngu~gı~ wa Thiong’o. Translations from Catalan: Deborah Bonner, Ita Roberts, Andrew Spence, Sarah Yandell Coordination and edition of the report: Humanities and Science Department, Institut Ramon Llull Design: Laura Estragués Editorial coordination: Critèria sccl. Printed by: Gramagraf, sccl ISBN: 84-96767-63-9 DL: B-45548-2007 Printed in Spain CONTENTS 7 Foreword, by Paul Auster 9 Presentations Translation and Linguistic Rights, by Jirˇí Gruša (International PEN) Participating in the Translation Debate, by Josep Bargalló (Institut Ramon Llull) 13 Introduction, by Esther Allen and Carles Torner 17 1. Translation, Globalization and English, by Esther Allen 1.1 English as an Invasive Species 1.2 World Literature and English 35 2. Literary Translation: The International Panorama, by Simona Škrabec and PEN centers from twelve countries 2.1 Projection Abroad 2.2 Acceptance of Translated Literature 49 3. Six Case Studies on Literary Translation 3.1 The Netherlands, by Bas Pauw 3.2 Argentina, by Gabriela Adamo 3.3 Catalonia, by Carme Arenas and Simona Škrabec 3.4 Germany, by Riky Stock 3.5 China, by Chen Maiping 3.6 France, by Anne-Sophie Simenel 93 4. Experiences in Literary Translation, by Esther Allen and Simona Škrabec 4.1 Experiences in the United States 4.2 Experiences in four European Countries 117 5. -

Chicago Chicago Fall 2015

UNIV ERSIT Y O F CH ICAGO PRESS 1427 EAST 60TH STREET CHICAGO, ILLINOIS 60637 KS OO B LL FA CHICAGO 2015 CHICAGO FALL 2015 FALL Recently Published Fall 2015 Contents General Interest 1 Special Interest 50 Paperbacks 118 Blood Runs Green Invisible Distributed Books 145 The Murder That Transfixed Gilded The Dangerous Allure of the Unseen Age Chicago Philip Ball Gillian O’Brien ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23889-0 Author Index 412 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24895-0 Cloth $27.50/£19.50 Cloth $25.00/£17.50 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23892-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-24900-1 COBE/EU Title Index 414 Subject Index 416 Ordering Inside Information back cover Infested Elephant Don How the Bed Bug Infiltrated Our The Politics of a Pachyderm Posse Bedrooms and Took Over the World Caitlin O’Connell Brooke Borel ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10611-3 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04193-3 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 Cloth $26.00/£18.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-10625-0 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-04209-1 Plankton Say No to the Devil Cover illustration: Lauren Nassef Wonders of the Drifting World The Life and Musical Genius of Cover design by Mary Shanahan Christian Sardet Rev. Gary Davis Catalog design by Alice Reimann and Mary Shanahan ISBN-13: 978-0-226-18871-3 Ian Zack Cloth $45.00/£31.50 ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23410-6 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-26534-6 Cloth $30.00/£21.00 E-book ISBN-13: 978-0-226-23424-3 JESSA CRISPIN The Dead Ladies Project Exiles, Expats, and Ex-Countries hen Jessa Crispin was thirty, she burned her settled Chica- go life to the ground and took off for Berlin with a pair of W suitcases and no plan beyond leaving. -

Literarische Imagination Und Soziologische Zeitdiagnose Im Wiedervereinigten Deutschland

LITERARISCHE IMAGINATION UND SOZIOLOGISCHE ZEITDIAGNOSE IM WIEDERVEREINIGTEN DEUTSCHLAND Untersuchungen zur Funktion von ›Welthaltigkeit‹ im deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsroman am Beispiel von Ingo Schulzes Simple Storys von Uwe Schumacher Staatsexamen in den Fächern Deutsch und Geschichte Freie Universität Berlin, 1994 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in German Literature University of Pittsburgh 2008 UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Uwe Schumacher It was defended on April 18th, 2008 and approved by Sabine von Dirke, PhD, Associate Professor John Lyon, PhD, Assistant Professor Randall Halle, PhD, Klaus W. Jonas Professor Stephen Brockmann, PhD, Professor Dissertation Director: Sabine von Dirke, PhD, Associate Professor ii Copyright © by Uwe Schumacher 2008 iii Sabine von Dirke, PhD, Associate Professor LITERARISCHE IMAGINATION UND SOZIOLOGISCHE ZEITDIAGNOSE IM WIEDERVEREINIGTEN DEUTSCHLAND Untersuchungen zur Funktion von ›Welthaltigkeit‹ im deutschsprachigen Gegenwartsroman am Beispiel von Ingo Schulzes Simple Storys Uwe Schumacher, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2008 This dissertation revitalizes the sociological approach to literature in the light of the ‘cultural turn’ in sociology represented by Pierre Bourdieu, Ulrich Beck, Gerhard Schulze and others – and demonstrates its potential for contemporary German-language literature. Advocating the decisive role of the social functions of cultural products, my investigation starts from the thesis that, with the electronic mass media acquiring a dominant role in the cultural sphere, a functional differen- tiation has taken place, forcing authors of artistic aspiration to focus on the media-specific strengths and benefits of literature as text while at the same urging them to adjust to the con- sumption patterns of mass entertainment – not least because literature as institution is increas- ingly permeated by the laws of a globalized market.