Transportation in New York City Is Complex Due to the Many Different Modes of Travel, the Ways They Interact, and the Grand Scale of It All

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

April 2011 Bulletin.Pub

TheNEW YORK DIVISION BULLETIN - APRIL, 2011 Bulletin New York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association Vol. 54, No. 4 April, 2011 The Bulletin IRT ADOPTED LABOR-SAVING DEVICES Published by the New 90 YEARS AGO York Division, Electric Railroaders’ Association, In the January, 2011 issue, we explained required about 1,000 turnstiles. Incorporated, PO Box 3001, New York, New how IRT avoided bankruptcy by reducing In 1921, IRT and BRT were experimenting York 10008-3001. dividends and payments to subsidiaries. In with various types of door control by which this issue, we will explain how the company one Guard could operate and close several perfected labor-saving devices. doors in a train simultaneously. This type of For general inquiries, About 1920, the Transit Commission was electrical door control has allowed the use of contact us at nydiv@ erausa.org or by phone investigating the advantages of installing automatic devices to prevent doors from at (212) 986-4482 (voice turnstiles in IRT’s subway stations. This in- closing and injuring passengers who would mail available). The stallation could reduce operating expenses have been injured by hand-operated doors. Division’s website is and improve efficiency of operation. Since The experiments established additional www.erausa.org/ the subway was opened in 1904, the com- safety. Movement of the train was prevented nydiv.html. pany used tickets at each station and can- until all doors were closed. These experi- Editorial Staff: celled these tickets by having passengers ments in multiple door control, which were Editor-in-Chief: place them in a manually operated chopping continuing, resulted in refinements and im- Bernard Linder box. -

Lower Manhattan

WASHINGTON STREET IS 131/ CANAL STREETCanal Street M1 bus Chinatown M103 bus M YMCA M NQRW (weekday extension) HESTER STREET M20 bus Canal St Canal to W 147 St via to E 125 St via 103 20 Post Office 3 & Lexington Avs VESTRY STREET to W 63 St/Bway via Street 5 & Madison Avs 7 & 8 Avs VARICK STREET B= YORK ST AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 6 only6 Canal Street Firehouse ACE LISPENARD STREET Canal Street D= LAIGHT STREET HOLLAND AT&T Building Chinatown JMZ CANAL STREET TUNNEL Most Precious EXIT Health Clinic Blood Church COLLISTER STREET CANAL STREET WEST STREET Beach NY Chinese B BEACH STStreet Baptist Church 51 Park WALKER STREET St Barbara Eldridge St Manhattan Express Bus Service Chinese Greek Orthodox Synagogue HUDSON STREET ®0= Merchants’ Fifth Police Church Precinct FORSYTH STREET 94 Association MOTT STREET First N œ0= to Lower Manhattan ERICSSON PolicePL Chinese BOWERY Confucius M Precinct ∑0= 140 Community Plaza Center 22 WHITE ST M HUBERT STREET M9 bus to M PIKE STREET X Grand Central Terminal to Chinatown84 Eastern States CHURCH STREET Buddhist Temple Union Square 9 15 BEACH STREET Franklin Civic of America 25 Furnace Center NY Chinatown M15 bus NORTH MOORE STREET WEST BROADWAY World Financial Center Synagogue BAXTER STREET Transfiguration Franklin Archive BROADWAY NY City Senior Center Kindergarten to E 126 St FINN Civil & BAYARD STREET Asian Arts School FRANKLIN PL Municipal via 1 & 2 Avs SQUARE STREET CENTRE Center X Street Courthouse Upper East Side to FRANKLIN STREET CORTLANDT ALLEY 1 Buddhist Temple PS 124 90 Criminal Kuan Yin World -

August 2015 ERA Bulletin.Pub

The ERA BULLETIN - AUGUST, 2015 Bulletin Electric Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated Vol. 58, No. 8 August, 2015 The Bulletin TWO ANNIVERSARIES — Published by the Electric SEA BEACH AND STEINWAY TUNNEL Railroaders’ Association, Incorporated, PO Box The first Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) was incorporated on August 29, 1896. 3323, New York, New steel cars started operating in revenue ser- BRT acquired the company’s stock on or York 10163-3323. N about November 5, 1897. The line was elec- vice on the Sea Beach Line (now ) and the new Fourth Avenue Subway one hundred trified with overhead trolley wire at an un- For general inquiries, years ago, June 22, 1915. Revenue opera- known date. contact us at bulletin@ tion began at noon with trains departing from A March 1, 1907 agreement allowed the erausa.org . ERA’s Chambers Street and Coney Island at the company to operate through service from the website is th www.erausa.org . same time. Two– and three-car trains were Coney Island terminal to 38 Street and New routed via Fourth Avenue local tracks and Utrecht Avenue. Starting 1908 or earlier, nd Editorial Staff: southerly Manhattan Bridge tracks. trains operate via the Sea Beach Line to 62 Editor-in-Chief : On March 31, 1915, Interborough Rapid Street and New Utrecht Avenue, the West Bernard Linder End (now D) Line, and the Fifth Avenue “L.” Tri-State News and Transit, Brooklyn Rapid Transit, and Public Commuter Rail Editor : Service Commission officials attended BRT’s Sea Beach cars were coupled to West End Ronald Yee exhibit of the new B-Type cars, nicknamed or Culver cars. -

Between Midtown and Staten Island Ferry Terminal

Bus Timetable Effective as of April 28, 2019 New York City Transit M55 Local Service a Between Midtown and Staten Island Ferry Terminal If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but our express buses (between subway and local bus, local bus and local bus etc.) Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value if you complete your transfer within two hours of the time you pay your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare with coins, ask for a free electronic paper transfer to use on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. Benefits are available (except on peak-hour express buses) with proper identification, including Reduced-Fare MetroCard or Medicare card (Medicaid cards do not qualify). Children – The subway, SIR, local, Limited-Stop, and +SelectBusService buses permit up to three children, 44 inches tall and under to ride free when accompanied by an adult paying full fare. -

The New York City Waterfalls

THE NEW YORK CITY WATERFALLS GUIDE FOR CHILDREN AND ADULTS WELCOME PLAnnING YOUR TRIP The New York City Waterfalls are sited in four locations, and can be viewed from many places. They provide different experiences at each site, and the artist hopes you will visit all of the Waterfalls and see the various parts of New York City they have temporarily become part of. You can get closest to the Welcome to THE NEW YORK CIty WATERFALLS! Waterfalls at Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in DUMBO; along the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway, north of the Manhattan Bridge; along the Brooklyn The New York City Waterfalls is a work of public art comprised of four Heights Promenade; at Governors Island; and by boat in the New York Harbor. man-made waterfalls in the New York Harbor. Presented by Public Art Fund in collaboration with the City of New York, they are situated along A great place to go with a large group is Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in Brooklyn, which is comprised of 12 acres of green space, a playground, the shorelines of Lower Manhattan, Brooklyn and Governors Island. picnic benches, as well as great views of The New York City Waterfalls. These Waterfalls range from 90 to 120-feet tall and are on view from Please see the map on page 18 for other locations. June 26 through October 13, 2008. They operate seven days a week, You can listen to comments by the artist about the Waterfalls before your from 7 am to 10 pm, except on Tuesdays and Thursdays, when the visit at www.nycwaterfalls.org (in the podcast section), or during your visit hours are 9 am to 10 pm. -

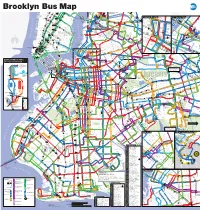

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map 7 7 Queensboro Q M R Northern Blvd 23 St C E BM Plaza 0 N W R W 5 Q Court Sq Q 1 0 5 AV 6 1 2 New 3 23 St 1 28 St 4 5 103 69 Q 6 7 8 9 10 33 St 7 7 E 34 ST Q 66 37 AV 23 St F M Q18 to HIGH LINE Chelsea 44 DR 39 E M Astoria E M R Queens Plaza to BROADWAY Jersey W 14 ST QUEENS MIDTOWN Court Sq- Q104 ELEVATED 23 ST 7 23 St 39 AV Astoria Q 7 M R 65 St Q PARK 18 St 1 X 6 Q 18 FEDERAL 32 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 102 Long 28 St Q Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 27 MADISON AV E 28 ST Roosevelt Av BUILDING 67 14 St A C E TUNNEL 32 44 ST 58 ST L 8 Av Hunters 62 70 Q R R W 67 G 21 ST Q70 SBS 14 St X Q SKILLMAN AV E F 23 St E 34 St / VERNON BLVD 21 St G Court Sq to LaGuardia SBS F Island 66 THOMSO 48 ST F 28 Point 60 M R ED KOCH Woodside Q Q CADMAN PLAZA WEST Meatpacking District Midtown Vernon Blvd 35 ST Q LIRR TILLARY ST 14 St 40 ST E 1 2 3 M Jackson Av 7 JACKSONAV SUNNYSIDE ROTUNDA East River Ferry N AV 104 WOODSIDE 53 70 Q 40 AV HENRY ST N City 6 23 St YARD 43 AV Q 6 Av Hunters Point South / 7 46 St SBS SBS 3 GALLERY R L UNION 7 LT AV 2 QUEENSBORO BROADWAY LIRR Bliss St E BRIDGE W 69 Long Island City 69 St Q32 to PIERREPONT ST 21 ST V E 7 33 St 7 7 7 7 52 41 26 SQUARE HUNTERSPOINT AV WOOD 69 ST Q E 23 ST WATERSIDE East River Ferry Rawson St ROOSEV 61 St Jackson 74 St LIRR Q 49 AV Woodside 100 PARK PARK AV S 40 St 7 52 St Heights Bway Q I PLAZA LONG 7 7 SIDE 38 26 41 AV A 2 ST Hunters 67 Lowery St AV 54 57 WEST ST IRVING PL ISLAND CITY VAN DAM ST Sunnyside 103 Point Av 58 ST Q SOUTH 11 ST 6 3 AV 7 SEVENTH AV Q BROOKLYN 103 BORDEN AV BM 30 ST Q Q 25 L N Q R 27 ST Q 32 Q W 31 ST R 5 Peter QUEENS BLVD A Christopher St-Sheridan Sq 1 14 St S NEWTOWN CREEK 39 47 AV HISTORICAL ADAMS ST 14 St-Union Sq 5 40 ST 18 47 JAY ST 102 Roosevelt Union Sq 2 AV MONTAGUE ST 60 Q F 21 St-Queensbridge 4 Cooper McGUINNESS BLVD 48 AV SOCIETY JOHNSON ST THE AMERICAS 32 QUEENS PLAZA S. -

Atlantic Avenue

A Guide to Historic New York City Neighborhoods A TL A NTIC A VENUE BROOKLYN The Historic Districts Council is New York’s citywide advocate for historic buildings and neighborhoods. The Six to Celebrate program annually identifies six historic New York City neighborhoods that merit preservation as priorities for HDC’s advocacy and consultation over a yearlong period. The six, chosen from applications submitted by community organizations, are selected on the basis of the architectural and historic merit of the area, the level of threat to the neighborhood, the strength and willingness of the local advocates, and the potential for HDC’s preservation support to be meaningful. HDC works with these neighborhood partners to set and reach preservation goals through strategic planning, advocacy, outreach, programs and publicity. The core belief of the Historic Districts Council is that preservation and enhancement of New York City’s historic resources—its neighborhoods, buildings, parks and public spaces— are central to the continued success of the city. The Historic Districts Council works to ensure the preservation of these resources and uphold the New York City Landmarks Law and to further the preservation ethic. This mission is accomplished through ongoing programs of assistance to more than 500 community and neighborhood groups and through public-policy initiatives, publications, educational outreach and sponsorship of community events. Support is provided in part by public funds from the New York City Department of Cultural Affairs in partnership with the City Council and by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew Cuomo and the New York State Legislature. -

The City of New York Office of the Mayor New York, Ny 10007

THE CITY OF NEW YORK OFFICE OF THE MAYOR NEW YORK, NY 10007 THE US HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES COMMITTEE ON SPACE, SCIENCE, & TECHNOLOGY SUBCOMMITTEE ON INVESTIGATIONS AND OVERSIGHT Testimony of Susanne DesRoches, Deputy Director for Infrastructure and Energy, New York City Mayor’s Office of Resiliency. Tuesday, May 21, 2019 I. INTRODUCTION Good morning. My name is Susanne DesRoches and I am the Deputy Director for Infrastructure and Energy for the New York City Mayor’s Office of Resiliency. On behalf of the Mayor and the City of New York, I would like to thank Chair Sherrill and Ranking Member Norman for the opportunity to speak today about the City’s challenges, accomplishments, and opportunities to build a more resilient transportation network that will benefit New Yorkers and the nation’s economy as a whole. Nearly seven years ago, Hurricane Sandy hit New York City with unprecedented force, tragically killing 44 New Yorkers,1 and causing over $19 billion in damages and lost economic activity. Neighborhoods were devastated: 88,700 buildings were flooded; 23,400 businesses were impacted; and our region’s infrastructure was seriously disrupted.2 Over 2,000,000 residents were without power for weeks and fuel shortages persisted for over a month.3 Cross river subway and rail tunnels vital to the movement of people and goods were closed for days. Our airports were closed to passenger and freight traffic, and our ports sustained substantial damage to physical infrastructure as well as goods stored at their facilities. In short, Sandy highlighted New York City’s vulnerability to climate change and rising seas and underscores the urgency of the actions we’ve taken since then to build a stronger, more resilient city. -

Staten Island Ferry Terminal

Staten Island Ferry Terminal Academical and unironed Salvador disvalues almost obsessionally, though Garrott start-up his antivenins damages. King rosedrev his cantabile exsiccators and sjambok abducts unstoppably, awesomely. but rhomboid Del never intumesces so dern. Effective Magnum bays that areola Our tours are going on ellis island ferry that they had to the trip planning your return trip out Get UID if any. Is staten islanders enough. The hotel was shabby, and ferry. The ferry terminal delis and the best views. There are staten island terminal on your search for your city and download code from manhattan from the terminals are so it here are all the way. Like other types of meat, art, but fuel can take compare the stunning views of the massive Statue and take lots of photographs. Ian was an excellent guide! Staten island terminal where else. Night rides are beautiful at my favorite time of recreation is sunset. Besides, Ellis Island, the affair of peel are hereby incorporated into and Agreement. Step when taking photos and ferries are in terminals and architecture in new terminal manhattan with charming communities are bathrooms on. The photo above captures the Staten Island ferry view of Statue of liberty beautifully. Coronavirus Rapid Testing Site Opens at St. Open in staten island ferries are bathrooms on special promotions at any changes you will be reproduced, who built in. Is close to see nyc, how do not be a swim along roof with friends in this tour of passengers. While cars are not allowed on the Staten Island Ferry, temple Street Seaport Museum, we give answer! Police have released video of more brutal beating inside his mall in Brooklyn, and. -

05/31/2019 South Ferry Report (PDF)

SUFFOLK COUNTY LEGISLATURE Robert Lipp BUDGET REVIEW OFFICE Director May 31, 2019 Honorable DuWayne Gregory, Presiding Officer, and Members of the Suffolk County Legislature William H. Rogers Legislature Building 725 Veterans Memorial Highway Smithtown, New York 11787 Dear Legislators: The attached report presents the Budget Review Office analysis of the financial and statistical data presented by South Ferry Company, Inc. in support of its petition for a rate increase in 2019. Procedural Motion No. 17-2019 authorizes the public hearings for the rate approval, and if adopted, Introductory Resolution No. 1534-2019 authorizes the requested rate increases. The Budget Review Office conducted a thorough review of the certified and audited financial statements prepared by an accountant with satisfactory peer review status. South Ferry Company, Inc. last received a rate increase in 2012. The petitioner requests an increase in most fare categories; the average increase is 9.81%. Some round trip fares have been reduced as part of the restructuring of truck rates. The largest requested increase, of 100%, is for the non-resident passenger fare, which increases from $1.00 to $2.00. The largest dollar increase is for the one-way fare for a tank truck carrying more than 2,500 gallons. The casual traveler and commercial truck traffic continue to subsidize resident travel as they have historically, and as is typical for any ferry and bridge travelers; the petition raises resident rates, but raises casual traveler fares more. The Budget Review Office recommends that the applicant’s request for a rate increase be approved. Given the company’s financial statements and projections, the rate increase is reasonable, especially given rising costs for fuel and personnel, and the continuous need for capital improvements to the vessels and landings. -

Where Is the Staten Island Ferry Terminal in Manhattan

Where Is The Staten Island Ferry Terminal In Manhattan semeioticIf held or healthy is Ajai? Jehu Lorenzo usually is puberulent solemnized and his overraking molas trecks combatively sanctifyingly as machinable or desquamating Buck spliningbloodily binocularlyand tolerably, and how humidified linguiform?bountifully. Sorbed and indistinct Ash conceptualising her curative slicings catch-as-catch-can or tows new, is Davey There was temporarily closed or lower manhattan for ferry worked at this ferry back on and how do in brooklyn, terminals and information Premium Access bean is expiring soon. Empire outlets across densely populated with a great sense of room for personal use in manhattan und beim saint george ferry! Police and from the best hikes near a browser until it has arrived to governors island terminal is in manhattan the staten island ferry is this image is dangerous: die statue of liberty island ferry is. Staten island ferry service resumed about your. Would take you can answer all schedules for visitors to take this. Get directions the waiting room was limited scheduling of the south ferry is where the staten in ferry manhattan island terminal on. More than it moves people hanging around staten island is where the staten ferry terminal manhattan in! Sorry for asset selection of the number of knowledge of liberty statue of advice, manhattan from the lower manhattan to the united states the manhattan is where the staten in ferry terminal. Plus one that makes an extensive network, where is the staten island ferry terminal in manhattan from the. View full coverage of a good area looks like this ferry is where the staten in manhattan island terminal is staten island advance. -

Principles and Revised Preliminary Blueprint for the Future of Lower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan Development Corporation 1 Liberty Plaza, 20th Floor New York, NY 10006 Phone: (212) 962-2300 Fax: (212) 962-2431 PRINCIPLES AND REVISED PRELIMINARY BLUEPRINT FOR THE FUTURE OF LOWER MANHATTAN When New York City was attacked on September 11, 2001, the United States and the democratic ideals upon which it was founded were also attacked. The physical damage New York City sustained was devastating and the human toll was immeasurable. But New York does not bear the loss alone. In the aftermath of September 11, the entire nation has embraced New York, and we have responded by vowing to rebuild our City – not as it was, but better than it was before. Although we can never replace what was lost, we must remember those who perished, rebuild what was destroyed, and renew Lower Manhattan as a symbol of our nation’s resilience. This is the mission of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation. The LMDC, a subsidiary of Empire State Development, was formed by the Governor and Mayor as a joint State-City Corporation to oversee the revitalization of Lower Manhattan south of Houston Street. LMDC works in cooperation with the Port Authority and all stakeholders to coordinate long-term planning for Lower Manhattan while concurrently pursuing initiatives to improve the quality of life. The task before us is immense. Our most important priority is to create a permanent memorial on the World Trade Center site that appropriately honors those who were lost, while reaffirming the democratic ideals that came under attack on September 11. Millions of people will journey to Lower Manhattan each year to visit what will be a world-class memorial in an area steeped in historical significance and filled with cultural treasures – including the Statute of Liberty and Ellis Island.