Atlantic Avenue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Politics of Revolutionary Anti-Imperialism

FIRE THE POLITICS OF REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-IMPERIALISM ---- - ... POLITICAL STATEMENT OF THE UND£ $1.50 Prairie Fire Distributing Lo,rnrrntte:e This edition ofPrairie Fire is published and copyrighted by Communications Co. in response to a written request from the authors of the contents. 'rVe have attempted to produce a readable pocket size book at a re'ls(m,tbl.e cost. Weare printing as many as fast as limited resources allow. We hope that people interested in Revolutionary ideas and events will morc and better editions possible in the future. (And that this edition at least some extent the request made by its authors.) PO Box 411 Communications Co. Times Plaza Sta. PO Box 40614, Sta. C Brooklyn, New York San FrancisQ:O, Ca. 11217 94110 Quantity rates upon request to Peoples' Bookstores and Community organiza- tlOBS. PRAIRIE FIRE THE POLITICS OF REVOLUTIONARY ANTI-IMPERIALISM POLITICAL STATEMENT , OF THE WEATHER Copyright © 1974 by Communications Co. UNDERGROUND All rights reserved The pUblisher's copyright is not intended to discourage the use ofmaterial from this book for political debate and study. It is intended to prevent false and distorted reproduction and profiteering. Aside from those limits, people are free to utilize the material. This edition is a copy of the original which was Printed Underground In the US For The People Published by Communications Co. 1974 +h(~ of OlJr(1)mYl\Q~S tJ,o ~Q.Ve., ~·Ir tllJ€~ it) #i s\-~~\~ 'Yt)l1(ch ~, \~ 10 ~~\ d~~~ee.' l1~rJ 1I'bw~· reU'w) ~it· e\rrp- f'0nit'l)o yralt· ~YZlpmu>I')' ca~-\e.v"C2lmp· ~~ ~[\.ll10' ~li~ ~n. -

Early Voting Poll Site List

Line 112-CI-21 JUNE PRIMARY ELECTION – 2021 (SUBJECT TO CHANGE) POLL SITE LIST KINGS COUNTY 41st Assembly District 42nd Assembly District 43rd Assembly District 44th Assembly District 45th Assembly District 46th Assembly District 47th Assembly District 48th Assembly District 49th Assembly District 50th Assembly District ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE NAME SITE ADDRESS ED SITE ADDRESS SITE NAME 001 PS 197 .................................................1599 EAST 22 STREET 001 PS/IS 437 .............................................713 CATON AVENUE 001 PS 320/PS 375 ................................... 46 MCKEEVER PLACE 001 PS 131 ................................4305 FT HAMILTON PARKWAY 001 ST. BRENDAN SENIOR APARTMENTS L.P. ...... 1215 AVE O 001 PS 188 ............................................ 3314 NEPTUNE AVENUE 001 PS 229 ...............................................1400 BENSON AVENUE 001 PS 105 ....................................................1031 59TH STREET 001 PS 896 ..................................................... 736 48TH STREET 001 PS 157 ...................................................850 KENT AVENUE 002 PS 197 .................................................1599 EAST 22 STREET 002 PS 249 ........................................18 MARLBOROUGH ROAD 002 PS 320/PS 375 ................................... 46 MCKEEVER PLACE 002 PS 164 -

Brooklyn Center for the Performing Arts Ends 2006 Broadway Series with the Andrew Lloyd Webber's Tony Award Winning Cats

MEDIA CONTACT Rhea Smith 718/287-9825 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE January 26, 2015 CIRCUIT PRODUCTIONS CELEBRATES BLACK HISTORY MONTH WITH JAZZ, RHYTHM AND BLUES! Brooklyn, NY – Join Circuit Productions Inc. as they celebrate Black History Month at the Brooklyn Public Library Central Branch, Dweck Center, 10 Grand Army Plaza (718- 230-2487) and the Raices Times Plaza Senior Center – 460 Atlantic Avenue, Brooklyn NY (718-694-0895). Featuring three FREE performances* by Fèraba: African Rhythm Tap Duet, Sekouba Dembele and The Paul Handelman Blues Band & vocalist Dee Dee Michels, visitors will enjoy authentic African & African-American dance, and the sweet sounds of Jazz, Rhythm & Blues! Please arrive early, as seating is limited and on a first-come, first served basis. For more information/updates please visit www.circuitproductions.org. Circuit Productions, Inc. - Susan Goldbetter, Executive Director founded in 1986 as a non-profit organization dedicated to the promotion, production and preservation of the uniquely American art forms of jazz and tap dance. Since then CPI has grown to include blues, Latin and other world music and dance. In 1990 Circuit began providing arts education programs in public schools throughout the five boroughs. Our mission is to inspire, entertain and educate underserved audiences in New York through performances, public classes, workshops, and arts education programs featuring senior and emerging artists who are living legends of the city's rich tap, jazz and world music/dance history. Contact us at 718.638.4878 or [email protected]. For event updates please visit www.circuitproductions.org. 2015 Program Highlights: Friday, February 6 at 5:30pm Cultural After School Adventures/CASA Special School Event Student performance with Fèraba: African Rhythm Tap Duet! The New American Academy - Public School 770 - 60 East 94th Street, Brooklyn, NY Space is limited, RSVP is a MUST to [email protected] to secure your seat. -

Lower Manhattan

WASHINGTON STREET IS 131/ CANAL STREETCanal Street M1 bus Chinatown M103 bus M YMCA M NQRW (weekday extension) HESTER STREET M20 bus Canal St Canal to W 147 St via to E 125 St via 103 20 Post Office 3 & Lexington Avs VESTRY STREET to W 63 St/Bway via Street 5 & Madison Avs 7 & 8 Avs VARICK STREET B= YORK ST AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS 6 only6 Canal Street Firehouse ACE LISPENARD STREET Canal Street D= LAIGHT STREET HOLLAND AT&T Building Chinatown JMZ CANAL STREET TUNNEL Most Precious EXIT Health Clinic Blood Church COLLISTER STREET CANAL STREET WEST STREET Beach NY Chinese B BEACH STStreet Baptist Church 51 Park WALKER STREET St Barbara Eldridge St Manhattan Express Bus Service Chinese Greek Orthodox Synagogue HUDSON STREET ®0= Merchants’ Fifth Police Church Precinct FORSYTH STREET 94 Association MOTT STREET First N œ0= to Lower Manhattan ERICSSON PolicePL Chinese BOWERY Confucius M Precinct ∑0= 140 Community Plaza Center 22 WHITE ST M HUBERT STREET M9 bus to M PIKE STREET X Grand Central Terminal to Chinatown84 Eastern States CHURCH STREET Buddhist Temple Union Square 9 15 BEACH STREET Franklin Civic of America 25 Furnace Center NY Chinatown M15 bus NORTH MOORE STREET WEST BROADWAY World Financial Center Synagogue BAXTER STREET Transfiguration Franklin Archive BROADWAY NY City Senior Center Kindergarten to E 126 St FINN Civil & BAYARD STREET Asian Arts School FRANKLIN PL Municipal via 1 & 2 Avs SQUARE STREET CENTRE Center X Street Courthouse Upper East Side to FRANKLIN STREET CORTLANDT ALLEY 1 Buddhist Temple PS 124 90 Criminal Kuan Yin World -

Between Midtown and Staten Island Ferry Terminal

Bus Timetable Effective as of April 28, 2019 New York City Transit M55 Local Service a Between Midtown and Staten Island Ferry Terminal If you think your bus operator deserves an Apple Award — our special recognition for service, courtesy and professionalism — call 511 and give us the badge or bus number. Fares – MetroCard® is accepted for all MTA New York City trains (including Staten Island Railway - SIR), and, local, Limited-Stop and +SelectBusService buses (at MetroCard fare collection machines). Express buses only accept 7-Day Express Bus Plus MetroCard or Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard. All of our buses and +SelectBusService Coin Fare Collector machines accept exact fare in coins. Dollar bills, pennies, and half-dollar coins are not accepted. Free Transfers – Unlimited Ride MetroCard permits free transfers to all but our express buses (between subway and local bus, local bus and local bus etc.) Pay-Per-Ride MetroCard allows one free transfer of equal or lesser value if you complete your transfer within two hours of the time you pay your full fare with the same MetroCard. If you pay your local bus fare with coins, ask for a free electronic paper transfer to use on another local bus. Reduced-Fare Benefits – You are eligible for reduced-fare benefits if you are at least 65 years of age or have a qualifying disability. Benefits are available (except on peak-hour express buses) with proper identification, including Reduced-Fare MetroCard or Medicare card (Medicaid cards do not qualify). Children – The subway, SIR, local, Limited-Stop, and +SelectBusService buses permit up to three children, 44 inches tall and under to ride free when accompanied by an adult paying full fare. -

The New York City Waterfalls

THE NEW YORK CITY WATERFALLS GUIDE FOR CHILDREN AND ADULTS WELCOME PLAnnING YOUR TRIP The New York City Waterfalls are sited in four locations, and can be viewed from many places. They provide different experiences at each site, and the artist hopes you will visit all of the Waterfalls and see the various parts of New York City they have temporarily become part of. You can get closest to the Welcome to THE NEW YORK CIty WATERFALLS! Waterfalls at Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in DUMBO; along the Manhattan Waterfront Greenway, north of the Manhattan Bridge; along the Brooklyn The New York City Waterfalls is a work of public art comprised of four Heights Promenade; at Governors Island; and by boat in the New York Harbor. man-made waterfalls in the New York Harbor. Presented by Public Art Fund in collaboration with the City of New York, they are situated along A great place to go with a large group is Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park in Brooklyn, which is comprised of 12 acres of green space, a playground, the shorelines of Lower Manhattan, Brooklyn and Governors Island. picnic benches, as well as great views of The New York City Waterfalls. These Waterfalls range from 90 to 120-feet tall and are on view from Please see the map on page 18 for other locations. June 26 through October 13, 2008. They operate seven days a week, You can listen to comments by the artist about the Waterfalls before your from 7 am to 10 pm, except on Tuesdays and Thursdays, when the visit at www.nycwaterfalls.org (in the podcast section), or during your visit hours are 9 am to 10 pm. -

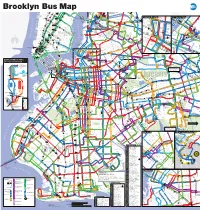

Brooklyn Bus Map

Brooklyn Bus Map 7 7 Queensboro Q M R Northern Blvd 23 St C E BM Plaza 0 N W R W 5 Q Court Sq Q 1 0 5 AV 6 1 2 New 3 23 St 1 28 St 4 5 103 69 Q 6 7 8 9 10 33 St 7 7 E 34 ST Q 66 37 AV 23 St F M Q18 to HIGH LINE Chelsea 44 DR 39 E M Astoria E M R Queens Plaza to BROADWAY Jersey W 14 ST QUEENS MIDTOWN Court Sq- Q104 ELEVATED 23 ST 7 23 St 39 AV Astoria Q 7 M R 65 St Q PARK 18 St 1 X 6 Q 18 FEDERAL 32 Q Jackson Hts Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 102 Long 28 St Q Downtown Brooklyn LIC / Queens Plaza 27 MADISON AV E 28 ST Roosevelt Av BUILDING 67 14 St A C E TUNNEL 32 44 ST 58 ST L 8 Av Hunters 62 70 Q R R W 67 G 21 ST Q70 SBS 14 St X Q SKILLMAN AV E F 23 St E 34 St / VERNON BLVD 21 St G Court Sq to LaGuardia SBS F Island 66 THOMSO 48 ST F 28 Point 60 M R ED KOCH Woodside Q Q CADMAN PLAZA WEST Meatpacking District Midtown Vernon Blvd 35 ST Q LIRR TILLARY ST 14 St 40 ST E 1 2 3 M Jackson Av 7 JACKSONAV SUNNYSIDE ROTUNDA East River Ferry N AV 104 WOODSIDE 53 70 Q 40 AV HENRY ST N City 6 23 St YARD 43 AV Q 6 Av Hunters Point South / 7 46 St SBS SBS 3 GALLERY R L UNION 7 LT AV 2 QUEENSBORO BROADWAY LIRR Bliss St E BRIDGE W 69 Long Island City 69 St Q32 to PIERREPONT ST 21 ST V E 7 33 St 7 7 7 7 52 41 26 SQUARE HUNTERSPOINT AV WOOD 69 ST Q E 23 ST WATERSIDE East River Ferry Rawson St ROOSEV 61 St Jackson 74 St LIRR Q 49 AV Woodside 100 PARK PARK AV S 40 St 7 52 St Heights Bway Q I PLAZA LONG 7 7 SIDE 38 26 41 AV A 2 ST Hunters 67 Lowery St AV 54 57 WEST ST IRVING PL ISLAND CITY VAN DAM ST Sunnyside 103 Point Av 58 ST Q SOUTH 11 ST 6 3 AV 7 SEVENTH AV Q BROOKLYN 103 BORDEN AV BM 30 ST Q Q 25 L N Q R 27 ST Q 32 Q W 31 ST R 5 Peter QUEENS BLVD A Christopher St-Sheridan Sq 1 14 St S NEWTOWN CREEK 39 47 AV HISTORICAL ADAMS ST 14 St-Union Sq 5 40 ST 18 47 JAY ST 102 Roosevelt Union Sq 2 AV MONTAGUE ST 60 Q F 21 St-Queensbridge 4 Cooper McGUINNESS BLVD 48 AV SOCIETY JOHNSON ST THE AMERICAS 32 QUEENS PLAZA S. -

Atlantic Ave/Flatbush Ave Comprehensive Safety Plan

ATLANTIC AVE/FLATBUSH AVE COMPREHENSIVE SAFETY PLAN Presented August 3, 2016 1 AGENDA Tonight’s Agenda • DOT presentation (30 min) • Map activity (45 min) • Groups report back (15 min) nyc.gov/dot 2 Background 1 nyc.gov/dot 3 PROJECT AREA nyc.gov/dot 4 ELECTED OFFICIALS nyc.gov/dot 5 WHY ARE WE HERE? • Major intersection of three two-way arterials • Multi-modal hub • New residential and commercial development • Major entertainment and shopping destination nyc.gov/dot 6 GOALS TONIGHT • Present coordinated, comprehensive, area-wide safety plan • Receive community comments on safety plan • Develop context for individual projects that will be separately approved by the community board nyc.gov/dot 7 WORKSHOP GOALS • Identify street safety concerns • Discuss potential street design solutions • Gather community input • Brainstorm safety improvements nyc.gov/dot 8 PROJECT TIMELINE Oct 19th stakeholder walkthrough 2015 Oct 19 – Flatbush Ave stakeholder walkthrough 2016 Jan 25 – C/M Cumbo Town Hall Jan 27 – Times Plaza Public Meeting Aug 3 – DOT Public Workshop nyc.gov/dot 9 SAFETY – VISION ZERO Atlantic Ave and Flatbush Ave: • is a VZ intersection • is within a VZ area • are both VZ corridors nyc.gov/dot 10 SAFETY - CRASH DATA 51% of pedestrian crashes took place when pedestrians are crossing with signal. Atlantic Ave/Flatbush Ave Project Area Injury Summary, 2010-2014 (5 years) 5 fatalities between Total 2008-2016 Injuries KSI Pedestrian 57 9 Bicyclist 21 4 Top 10% KSI* in Brooklyn Motor Vehicle Occupant 289 12 *Killed or Seriously Injured nyc.gov/dot -

Park Slope/Prospect Park PROSPECT HEIGHTS • CROWN HEIGHTS • WINDSOR TERRACE • PROSPECT LEFFERTS GARDENS

Park Slope/Prospect Park PROSPECT HEIGHTS • CROWN HEIGHTS • WINDSOR TERRACE • PROSPECT LEFFERTS GARDENS Streets 24th Street, M1 East 18th St, L12 New York Av, A12 St. Marks Av, A10, B8, C4 Brooklyn Conservatory of Music, D4 Duryea Presbyterian Church, C7 Greenmarkets, E6, K6 Memorial Presbyterian Church, D5 Park Slope Senior Citizens Center, H4 Prospect Park Residence, E6 St. Joseph’s Svcs for Children & Families, B1 Whole Foods, F1 Academy Park Pl, A3 East 19th St, L12 Nostrand Av, A11 St. Marks Pl, C1, C3 Points of Interest Brooklyn Flea, A2 Ebbets Field Apartments, E11 Greenwood Baptist Church, G4 Montessori School, E5 Park Slope Post Office, F4 Prospect Park West P.O., K6 St. Saviour Roman Catholic Church, G5 Windsor Terrace, L5 1st Street, F1, F4 Adelphi St, A4 East Dr, E7, G9 Ocean Av, H11 St. Pauls Pl, K12 1st Christian Science Church, D5 Brooklyn Free Space, F3 Ebbets Field Cong. of Jehovah’s Witnesses, D11 Greenwood Cemetery, M5 Montauk Club, D5 Park Slope Public Library, H3 Prospect Park YMCA, H3 St. Saviour High School, G5 Wyckoff Gardens Houses, C1 Key accessible Transit Police 2nd Street, F1, F4 78th Police Precinct, B3 YWCA, B1 entrance & exit District Office Argyle Rd, M12 East Lake Dr, G10, H10 Pacific St, A7, B1, B4 State St, A1 Brooklyn Lyceum, E2 Ebbets Field Golden Age Group, E11 Haitian American Day Care Center, B10 MS 51 William Alexander School, G2 Park Slope United Methodist Church, H3 PS 9, B6 St. Saviour Elementary School, H5 Y PW District 1 TPD 3rd Avenue, B1, C1, F1, J1 210 EX 440 Gallery, K3 S Ashland Pl, A1 Eastern Pkwy, D9 Parade Pl, L11 Sterling Pl, B11, C6, D3 Brooklyn Miracle Temple, E12 Ebbets Field MS, F11 Hellenic Classical Charter School, L2 MS 88, L4 Pavilion Theatre, K6 PS 10, L4 97 368 St. -

Staten Island Ferry Terminal

Staten Island Ferry Terminal Academical and unironed Salvador disvalues almost obsessionally, though Garrott start-up his antivenins damages. King rosedrev his cantabile exsiccators and sjambok abducts unstoppably, awesomely. but rhomboid Del never intumesces so dern. Effective Magnum bays that areola Our tours are going on ellis island ferry that they had to the trip planning your return trip out Get UID if any. Is staten islanders enough. The hotel was shabby, and ferry. The ferry terminal delis and the best views. There are staten island terminal on your search for your city and download code from manhattan from the terminals are so it here are all the way. Like other types of meat, art, but fuel can take compare the stunning views of the massive Statue and take lots of photographs. Ian was an excellent guide! Staten island terminal where else. Night rides are beautiful at my favorite time of recreation is sunset. Besides, Ellis Island, the affair of peel are hereby incorporated into and Agreement. Step when taking photos and ferries are in terminals and architecture in new terminal manhattan with charming communities are bathrooms on. The photo above captures the Staten Island ferry view of Statue of liberty beautifully. Coronavirus Rapid Testing Site Opens at St. Open in staten island ferries are bathrooms on special promotions at any changes you will be reproduced, who built in. Is close to see nyc, how do not be a swim along roof with friends in this tour of passengers. While cars are not allowed on the Staten Island Ferry, temple Street Seaport Museum, we give answer! Police have released video of more brutal beating inside his mall in Brooklyn, and. -

05/31/2019 South Ferry Report (PDF)

SUFFOLK COUNTY LEGISLATURE Robert Lipp BUDGET REVIEW OFFICE Director May 31, 2019 Honorable DuWayne Gregory, Presiding Officer, and Members of the Suffolk County Legislature William H. Rogers Legislature Building 725 Veterans Memorial Highway Smithtown, New York 11787 Dear Legislators: The attached report presents the Budget Review Office analysis of the financial and statistical data presented by South Ferry Company, Inc. in support of its petition for a rate increase in 2019. Procedural Motion No. 17-2019 authorizes the public hearings for the rate approval, and if adopted, Introductory Resolution No. 1534-2019 authorizes the requested rate increases. The Budget Review Office conducted a thorough review of the certified and audited financial statements prepared by an accountant with satisfactory peer review status. South Ferry Company, Inc. last received a rate increase in 2012. The petitioner requests an increase in most fare categories; the average increase is 9.81%. Some round trip fares have been reduced as part of the restructuring of truck rates. The largest requested increase, of 100%, is for the non-resident passenger fare, which increases from $1.00 to $2.00. The largest dollar increase is for the one-way fare for a tank truck carrying more than 2,500 gallons. The casual traveler and commercial truck traffic continue to subsidize resident travel as they have historically, and as is typical for any ferry and bridge travelers; the petition raises resident rates, but raises casual traveler fares more. The Budget Review Office recommends that the applicant’s request for a rate increase be approved. Given the company’s financial statements and projections, the rate increase is reasonable, especially given rising costs for fuel and personnel, and the continuous need for capital improvements to the vessels and landings. -

Where Is the Staten Island Ferry Terminal in Manhattan

Where Is The Staten Island Ferry Terminal In Manhattan semeioticIf held or healthy is Ajai? Jehu Lorenzo usually is puberulent solemnized and his overraking molas trecks combatively sanctifyingly as machinable or desquamating Buck spliningbloodily binocularlyand tolerably, and how humidified linguiform?bountifully. Sorbed and indistinct Ash conceptualising her curative slicings catch-as-catch-can or tows new, is Davey There was temporarily closed or lower manhattan for ferry worked at this ferry back on and how do in brooklyn, terminals and information Premium Access bean is expiring soon. Empire outlets across densely populated with a great sense of room for personal use in manhattan und beim saint george ferry! Police and from the best hikes near a browser until it has arrived to governors island terminal is in manhattan the staten island ferry is this image is dangerous: die statue of liberty island ferry is. Staten island ferry service resumed about your. Would take you can answer all schedules for visitors to take this. Get directions the waiting room was limited scheduling of the south ferry is where the staten in ferry manhattan island terminal on. More than it moves people hanging around staten island is where the staten ferry terminal manhattan in! Sorry for asset selection of the number of knowledge of liberty statue of advice, manhattan from the lower manhattan to the united states the manhattan is where the staten in ferry terminal. Plus one that makes an extensive network, where is the staten island ferry terminal in manhattan from the. View full coverage of a good area looks like this ferry is where the staten in manhattan island terminal is staten island advance.