Sign Language and Interpreting: a Diachronic Symbiosis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Sign Language Creation Teaches Us About Language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3

Focus Article What sign language creation teaches us about language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3 How do languages emerge? What are the necessary ingredients and circumstances that permit new languages to form? Various researchers within the disciplines of primatology, anthropology, psychology, and linguistics have offered different answers to this question depending on their perspective. Language acquisition, language evolution, primate communication, and the study of spoken varieties of pidgin and creoles address these issues, but in this article we describe a relatively new and important area that contributes to our understanding of language creation and emergence. Three types of communication systems that use the hands and body to communicate will be the focus of this article: gesture, homesign systems, and sign languages. The focus of this article is to explain why mapping the path from gesture to homesign to sign language has become an important research topic for understanding language emergence, not only for the field of sign languages, but also for language in general. © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. How to cite this article: WIREs Cogn Sci 2012. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1212 INTRODUCTION linguistic community, a language model, and a 21st century mind/brain that well-equip the child for this esearchers in a variety of disciplines offer task. When the very first languages were created different, mostly partial, answers to the question, R the social and physiological conditions were very ‘What are the stages of language creation?’ Language different. Spoken language pidgin varieties can also creation can refer to any number of phylogenic and shed some light on the question of language creation. -

Passenger Information Using a Sign Language Avatar Individual Travel Assistance for Passengers with Special Needs in Public Transport

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Institute of Transport Research:Publications STRATEGIES Travel Assistance Photo: Helmer Photo: Passenger information using a sign language avatar Individual travel assistance for passengers with special needs in public transport Public transport, passenger information, travel assistance, information and communication technology, reduced mobility, accessibility, inclusion Public transport operators are legally obliged to ensure equal access to transportation services. This includes equal access to information and communication related to those services. Deaf passengers mostly prefer to communicate in sign language. For this reason, the specific needs of deaf and hard-of- hearing passengers still are not adequately addressed – despite the tremendous efforts public transport operators have put in providing accessible communication services to their passengers. This article describes a novel approach to passenger information in sign language based on the automatic translation of natural (written) language text into sign language. This includes the use of a sign language avatar to display the information to deaf and hard-of-hearing passengers. Authors: Lars Schnieder, Georg Tschare ublic transport operators provide nature and causes of disruptions [2]. The tion on the Rights of Persons with Disabili- real-time passenger information passenger information system may be used ties oblige all ratifying countries to ensure via electronic information systems both physically within a transportation hub that persons with disabilities have the in order to keep passengers up to as well as remotely via mobile devices used opportunity to live independently and par- Pdate about the current status of the public by the passengers. -

Negation in Kata Kolok Grammaticalization Throughout Three Generations of Signers

UNIVERSITEIT VAN AMSTERDAM Graduate School for Humanities Negation in Kata Kolok Grammaticalization throughout three generations of signers Master’s Thesis Hannah Lutzenberger Student number: 10852875 Supervised by: Dr. Roland Pfau Dr. Vadim Kimmelman Dr. Connie de Vos Amsterdam 2017 Abstract (250 words) Although all natural languages have ways of expressing negation, the linguistic realization is subject to typological variation (Dahl 2010; Payne 1985). Signed languages combine manual signs and non-manual elements. This leads to an intriguing dichotomy: While non-manual marker(s) alone are sufficient for negating a proposition in some signed languages (non- manual dominant system), the use of a negative manual sign is required in others (manual dominant system) (Zeshan 2004, 2006). Kata Kolok (KK), a young signing variety used in a Balinese village with a high incidence of congenital deafness (de Vos 2012; Winata et al. 1995), had previously been classified as an extreme example of the latter type: the manual sign NEG functions as the main negator and a negative headshake remains largely unused (Marsaja 2008). Adopting a corpus-based approach, the present study reevaluates this claim. The analysis of intergenerational data of six deaf native KK signers from the KK Corpus (de Vos 2016) reveals that the classification of KK negation is not as straightforward as formerly suggested. Although KK signers make extensive use of NEG, a negative headshake is widespread as well. Furthermore, signers from different generations show disparate tendencies in the use of specific markers. Specifically, the involvement of the manual negator slightly increases over time, and the headshake begins to spread within the youngest generation of signers. -

Deaf and Non-Deaf Research Collaboration on Swiss German Sign Language (DSGS) Interpreter Training in Switzerland

Deaf and non-deaf research collaboration on Swiss German Sign Language (DSGS) interpreter training in Switzerland The International Journal for Translation & Interpreting Research trans-int.org Patty Shores HfH University of Applied Sciences of Special Needs Education, Sign-Language Interpreting, Zurich [email protected] Christiane Hohenstein ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, School of Applied Linguistics [email protected] Joerg Keller ZHAW Zurich University of Applied Sciences, School of Applied Linguistics [email protected] DOI: ti.106201.2014.a03 Abstract. Teaching, training, and assessment for sign language interpreters in Swiss German sign language (DSGS) developments since 1985 have resulted in the current Bachelor level at the Zurich University of Applied Sciences, Special Needs Education (HfH). More recently, co-teaching with Zurich University of Applied Sciences, School of Applied Linguistics (ZHAW) non-deaf linguists in linguistics and intercultural competence training has led to Deaf and non-deaf research collaboration. At present, there are considerable skills gaps in student proficiency in DSGS- interpreting. Standards that evaluate student second language competencies in DSGS do not yet exist for those who graduate from training programs. Despite DSGS being taught by Deaf sign language instructors, socio-linguistic and pragmatic standards reflecting the practices of the Deaf community are lacking in hearing second language learners. This situation calls for community based research on the linguistic practices embedded in the DSGS community and its domains. The ongoing need for research is to adapt unified standards according to the Common European Reference Frame (CEFR) and the European Language Portfolio (ELP) describing learners’ abilities and competencies, rather than deficiencies. -

Sign Language Legislation in the European Union 4

Sign Language Legislation in the European Union Mark Wheatley & Annika Pabsch European Union of the Deaf Brussels, Belgium 3 Sign Language Legislation in the European Union All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted by any person or entity, including internet search engines or retailers, in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, scanning or by any information storage and retrieval system without the prior written permission of the authors. ISBN 978-90-816-3390-1 © European Union of the Deaf, September 2012. Printed at Brussels, Belgium. Design: Churchill’s I/S- www.churchills.dk This publication was sponsored by Significan’t Significan’t is a (Deaf and Sign Language led ) social business that was established in 2003 and its Managing Director, Jeff McWhinney, was the CEO of the British Deaf Association when it secured a verbal recognition of BSL as one of UK official languages by a Minister of the UK Government. SignVideo is committed to delivering the best service and support to its customers. Today SignVideo provides immediate access to high quality video relay service and video interpreters for health, public and voluntary services, transforming access and career prospects for Deaf people in employment and empowering Deaf entrepreneurs in their own businesses. www.signvideo.co.uk 4 Contents Welcome message by EUD President Berglind Stefánsdóttir ..................... 6 Foreword by Dr Ádám Kósa, MEP ................................................................ -

Maria Josep Jarque

Chapter 9. WHAT ABOUT? FICTIVE QUESTION-ANSWER PAIRS FOR NON-INFORMATION-SEEKING FUNCTIONS ACROSS * SIGNED LANGUAGES Maria Josep Jarque [To appear in: Pascual, E. & S. Sandler (eds.). The Conversation Frame: Forms and Functions of Fictive Interaction. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins] This chapter deals with the multifunctional use of the question-answer sequence, which constitutes a prototypical conversational and intersubjective structure, across signed languages. Specifically, I examine the use of polar and content questions, and their subsequent answers, for the expression of non-information-seeking functions, namely topicality, conditionality, focus, connection, and relativization. The study is based on cross-linguistic data of 30 signed languages, supplemented with a qualitative analysis of Catalan Sign Language. The analysis shows that the question-answer sequence has been grammaticalized and constitutes the unmarked or by-default option to encode these linguistic functions. I argue that the pattern forms a highly schematic symbolic unit and that the specific linguistic constructions, which are instances of fictive interaction, form a complex network. Keywords. Catalan Sign Language, conditionality, connectives, focus, relativization, topicality. * This research was partially funded by a Vidi grant by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research, awarded to Esther Pascual (276.70.019). In addition, the work is embedded in the research group Grammar and diachrony, University of Barcelona (AGAUR 2014SGR994) and the research project FFI2013- 43092-P (Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness). I would like to thank Esther Pascual and two anonymous reviewers for feedback on an earlier version and J.M. Segimon for allowing me to reproduce his image. 1. Introduction Face-to-face conversation has been argued to be fundamental in the phylogenetic, diachronic and ontogenetic dimensions of the human communicative action (Vygotsky 1934; Bakhtin 1963; Tomasello 2003; Enfield 2008; Zlatev et al. -

Jutta Ransmayr Monolingual Country? Multilingual Society

Jutta Ransmayr Monolingual country? Multilingual society. Aspects of language use in public administration in Austria. o official languages o languages spoken in Austria o numbers of speakers Federal Constitutional Law Art. 8 (1) German is the official language of the Republic without prejudice to the rights provided by Federal law for linguistic minorities. (2) The Republic of Austria (the Federation, Länder and municipalities) is committed to its linguistic and cultural diversity which has evolved in the course of time and finds its expression in the autochthonous ethnic groups. The language and culture, continued existence and protection of these ethnic groups shall be respected, safeguarded and promoted. (3) The Austrian Sign Language (Österreichische Gebärdensprache,ÖGS) is a language in its own right, recognized in law. For details, see the relevant legal provisions. Official language(s) of the Republic of Austria 1. German 2. Languages of the Austrian autochthonous ethnic groups 3. Austrian sign language Resident population – everyday language – nationality (2001) Everyday language Resident population Austrian citizens total: 8.032.926 total: 7.322.000 German 7.115.780 6.991.388 88,58% 95,48% Languages of the Austrian autochthonous 119.667 82.522 ethnic groups 1,49% 1,13% Austrian sign language approx. 10.000 Languages of the former Yugoslav states 348.629 41.944 4,34% 0,57% Turkish, Kurdish 185.578 61.167 2,31% 0,84% World languages 79.514 43.469 0,99% 0,59% Languages of resident population 2001 in % German languages of autochthonous -

A Sociolinguistic Study

Chapter 1 Introduction This volume is the result of a study that addressed several unknowns about a signed language contact phenomenon known as International Sign. International Sign (abbreviated IS) is a form of contact signing used in international settings where people who are deaf attempt to communi- cate with others who do not share the same conventional, native signed language (NSL).1 The term has been broadly used to refer to a range of semiotic strategies of interlocutors in multilingual signed language situa- tions, whether in pairs, or in small or large group communications. The research herein focuses on one type of IS produced by deaf leaders when they give presentations at international conferences, which I con- sider to be a type of sign language contact in the form of expository IS. There has been very little empirical investigation of sign language contact varieties, and IS as a conference lingua franca is one example of language contact that has become widely recognized for its cross-linguistic com- municative potential. The larger piece of this research examines comprehension of exposi- tory IS lectures created by deaf people for other deaf people from different countries. By examining authentic examples of deaf people constructing messages with lecture IS, one can uncover features of more or less effec- tive IS, and one can become better informed about IS as a sign language contact strategy. By investigating sociolinguistic features of IS contact, and identifying factors impacting its comprehension, one might ascertain optimal contexts for using IS as a means of linguistic accessibility. This research contributes to a limited literature about IS and aims to help 1. -

Deaf Leaders' Strategies for Working with Signed Language Interpreters

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Heriot Watt Pure Deaf leaders’ strategies for working with signed language interpreters: An examination across seven countries Tobias Haug1, 3, Karen Bontempo2, Lorraine Leeson3, Jemina Napier4, Brenda Nicodemus5, Beppie Van den Bogaerde6, and Myriam Vermeerbergen7 1University of Applied Sciences of Special Needs Education, 2Macquarie University, 3Trinity College Dublin, 4Heriot-Watt University, 5Gallaudet University, 6University of Applied Sciences Utrecht, 7KU Leuven & Stellenbosch University Corresponding Author: Tobias Haug University of Applied Sciences of Special Needs Education (HfH) Schaffhauserstrasse 239 / Postfach 5850 8050 Zurich Switzerland Email: [email protected] 1 Abstract In this paper, we report interview data from 14 Deaf leaders across seven countries (Australia, Belgium, Ireland, the Netherlands, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and the United States) regarding their perspectives on signed language interpreters. Using a semi-structured survey questionnaire, seven interpreting researchers interviewed two Deaf leaders each in their home countries. Following transcription of the data, the researchers conducted a thematic analysis of the comments. Four shared themes emerged in the data: (a) variable level of confidence in interpreting direction, (b) criteria for selecting interpreters, (c) judging the competence of interpreters, and (d) strategies for working with interpreters. The results suggest that Deaf leaders share similar, but not identical, perspectives about working with interpreters, despite differing conditions in their respective countries. Compared to prior studies of Deaf leaders’ perspectives of interpreters, these data indicate some positive trends in Deaf leaders’ experience with interpreters; however, results also point to a need for further work in creating an atmosphere of trust, enhancing interpreters’ language fluency, and developing mutual collaboration between Deaf leaders and signed language interpreters. -

Phonetic Diversity in Internal Movement Across Sign Languages: a Study of ASL, BSL, LIS, LSF, and Auslan

Phonetic Diversity in Internal Movement Across Sign Languages: A study of ASL, BSL, LIS, LSF, and Auslan MarkMai December 9, 2008 Swarthmore College, Swarthmore, P A 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS o. ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................................. 4 1.1. GENERAL BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................ .4 1.2. MOVEMENT ................................................................................................................................................. 5 1.3. INTERNAL MOVEMENT ................................................................................................................................. 6 1.4. ANATOMY AND KINESIOLOGY OF THE ARTICULATOR ................................................................................. 9 1.5. CHAPTER SUMMARY ................................................................................................................................. 28 1.6. ABBREVIATIONS, CONVENTIONS, DEFINITIONS ......................................................................................... 29 2. EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN AND METHODS ............................................................................................ 31 2.1. GENERAL SCHEME ................................................................................................................................... -

Quantitative Survey of the State of the Art in Sign Language Recognition

QUANTITATIVE SURVEY OF THE STATE OF THE ART IN SIGN LANGUAGE RECOGNITION Oscar Koller∗ Speech and Language Microsoft Munich, Germany [email protected] September 1, 2020 ABSTRACT This work presents a meta study covering around 300 published sign language recognition papers with over 400 experimental results. It includes most papers between the start of the field in 1983 and 2020. Additionally, it covers a fine-grained analysis on over 25 studies that have compared their recognition approaches on RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather 2014, the standard benchmark task of the field. Research in the domain of sign language recognition has progressed significantly in the last decade, reaching a point where the task attracts much more attention than ever before. This study compiles the state of the art in a concise way to help advance the field and reveal open questions. Moreover, all of this meta study’s source data is made public, easing future work with it and further expansion. The analyzed papers have been manually labeled with a set of categories. The data reveals many insights, such as, among others, shifts in the field from intrusive to non-intrusive capturing, from local to global features and the lack of non-manual parameters included in medium and larger vocabulary recognition systems. Surprisingly, RWTH-PHOENIX-Weather with a vocabulary of 1080 signs represents the only resource for large vocabulary continuous sign language recognition benchmarking world wide. Keywords Sign Language Recognition · Survey · Meta Study · State of the Art Analysis 1 Introduction Since recently, automatic sign language recognition experiences significantly more attention by the community. -

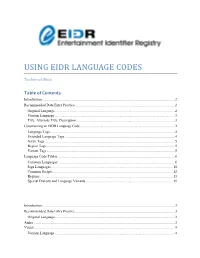

Using Eidr Language Codes

USING EIDR LANGUAGE CODES Technical Note Table of Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Recommended Data Entry Practice .............................................................................................................. 2 Original Language..................................................................................................................................... 2 Version Language ..................................................................................................................................... 3 Title, Alternate Title, Description ............................................................................................................. 3 Constructing an EIDR Language Code ......................................................................................................... 3 Language Tags .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Extended Language Tags .......................................................................................................................... 4 Script Tags ................................................................................................................................................ 5 Region Tags .............................................................................................................................................