A Sociolinguistic Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

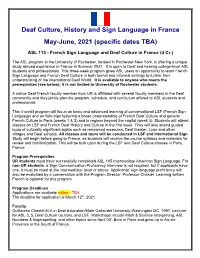

Deaf Culture, History and Sign Language in France May-June, 2021 (Specific Dates TBA)

Deaf Culture, History and Sign Language in France May-June, 2021 (specific dates TBA) ASL 113 - French Sign Language and Deaf Culture in France (4 Cr.) The ASL program at the University of Rochester, located in Rochester New York, is offering a unique study abroad experience in France in Summer 2021. It is open to Deaf and hearing college-level ASL students and professionals. This three-week program gives ASL users an opportunity to learn French Sign Language and French Deaf Culture in both formal and informal settings to further their understanding of the international Deaf World. It is available to anyone who meets the prerequisites (see below); it is not limited to University of Rochester students. A native Deaf French faculty member from UR is affiliated with several faculty members in the Deaf community and they jointly plan the program, schedule, and curriculum offered to ASL students and professionals. This 4-credit program will focus on basic and advanced learning of conversational LSF (French Sign Language) and on field trips fostering a broad understanding of French Deaf Culture and general French Culture in Paris (weeks 1 & 2) and in regions beyond the capital (week 3). Students will attend classes on LSF and French Deaf History and Culture in the first week. They will also attend guided tours of culturally significant sights such as renowned museums, Deaf theater, Lyon and other villages and Deaf schools. All classes and tours will be conducted in LSF and International Sign. Study will begin before going to France, as students will receive the course syllabus and materials for review and familiarization. -

Sign Language Typology Series

SIGN LANGUAGE TYPOLOGY SERIES The Sign Language Typology Series is dedicated to the comparative study of sign languages around the world. Individual or collective works that systematically explore typological variation across sign languages are the focus of this series, with particular emphasis on undocumented, underdescribed and endangered sign languages. The scope of the series primarily includes cross-linguistic studies of grammatical domains across a larger or smaller sample of sign languages, but also encompasses the study of individual sign languages from a typological perspective and comparison between signed and spoken languages in terms of language modality, as well as theoretical and methodological contributions to sign language typology. Interrogative and Negative Constructions in Sign Languages Edited by Ulrike Zeshan Sign Language Typology Series No. 1 / Interrogative and negative constructions in sign languages / Ulrike Zeshan (ed.) / Nijmegen: Ishara Press 2006. ISBN-10: 90-8656-001-6 ISBN-13: 978-90-8656-001-1 © Ishara Press Stichting DEF Wundtlaan 1 6525XD Nijmegen The Netherlands Fax: +31-24-3521213 email: [email protected] http://ishara.def-intl.org Cover design: Sibaji Panda Printed in the Netherlands First published 2006 Catalogue copy of this book available at Depot van Nederlandse Publicaties, Koninklijke Bibliotheek, Den Haag (www.kb.nl/depot) To the deaf pioneers in developing countries who have inspired all my work Contents Preface........................................................................................................10 -

Download Full Issue In

Theory and Practice in Language Studies ISSN 1799-2591 Volume 9, Number 11, November 2019 Contents REGULAR PAPERS Adoption of Electronic Techniques in Teaching English-Yoruba Bilingual Youths the Semantic 1369 Expansion and Etymology of Yoruba Words and Statements B T Opoola and A F, Opoola EFL Instructors’ Performance Evaluation at University Level: Prescriptive and Collaborative 1379 Approaches Thaer Issa Tawalbeh Lexico-grammatical Analysis of Native and Non-native Abstracts Based on Halliday’s SFL Model 1388 Massome Raeisi, Hossein Vahid Dastjerdi, and Mina Raeisi A Corpus-based 3M Approach to the Teaching of English Unaccusative Verbs 1396 Junhua Mo A Study on Object-oriented Adverbials in Mandarin from a Cognitive Perspective 1403 Linze Li Integrating Multiple Intelligences in the EFL Syllabus: Content Analysis 1410 Salameh S. Mahmoud and Mamoon M. Alaraj A Spatial Analysis of Isabel Archer in The Portrait of a Lady 1418 Chenying Bai Is the Spreading of Internet Neologisms Netizen-Driven or Meme-driven? Diachronic and Synchronic 1424 Study of Chinese Internet Neologism Tuyang Tusen Po Zongwei Song Recreating the Image of a “Chaste Wife”: Transitivity in Two Translations of Chinese Ancient Poem 1433 Jie Fu Yin Shilong Tao Evokers of the Divine Message: Mysticism of American Transcendentalism in Emerson’s “Nature” 1442 and the Mystic Thought in Rumi’s Masnavi Amirali Ansari and Hossein Jahantigh 1449 Huaiyu Mu Analysis on Linguistic Art of Broadcasting in the New Media Era 1454 Chunli Wang A Critical Evaluation of Krashen’s Monitor Model 1459 Wen Lai and Lifang Wei ISSN 1799-2591 Theory and Practice in Language Studies, Vol. -

A Study of Lexical Variation, Comprehension and Language

A Study of Lexical Variation, Comprehension and Language Attitudes in Deaf Users of Chinese Sign Language (CSL) from Beijing and Shanghai Yunyi Ma UCL Ph.D. in Psychology and Language Science I, Yunyi Ma, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. The ethics for this project have been approved by UCL’s Ethics Committee (Project ID Number: EPI201503). Signed: ii Abstract Regional variation between the Beijing and Shanghai varieties, particularly at the lexical level, has been observed by sign language researchers in China (Fischer & Gong, 2010; Shen, 2008; Yau, 1977). However, few investigations into the variation in Chinese Sign Language (CSL) from a sociolinguistic perspective have previously been undertaken. The current study is the first to systematically study sociolinguistic variation in CSL signers’ production and comprehension of lexical signs as well as their language attitudes. This thesis consists of three studies. The first study investigates the lexical variation between Beijing and Shanghai varieties. Results of analyses show that age, region and semantic category are the factors influencing lexical variation in Beijing and Shanghai signs. To further explore the findings of lexical variation, a lexical recognition task was undertaken with Beijing and Shanghai signers in a second study looking at mutual comprehension of lexical signs used in Beijing and Shanghai varieties. The results demonstrate that Beijing participants were able to understand more Shanghai signs than Shanghai participants could understand Beijing signs. Historical contact is proposed in the study as a possible major cause for the asymmetrical intelligibility between the two varieties. -

Sign Language Endangerment and Linguistic Diversity Ben Braithwaite

RESEARCH REPORT Sign language endangerment and linguistic diversity Ben Braithwaite University of the West Indies at St. Augustine It has become increasingly clear that current threats to global linguistic diversity are not re - stricted to the loss of spoken languages. Signed languages are vulnerable to familiar patterns of language shift and the global spread of a few influential languages. But the ecologies of signed languages are also affected by genetics, social attitudes toward deafness, educational and public health policies, and a widespread modality chauvinism that views spoken languages as inherently superior or more desirable. This research report reviews what is known about sign language vi - tality and endangerment globally, and considers the responses from communities, governments, and linguists. It is striking how little attention has been paid to sign language vitality, endangerment, and re - vitalization, even as research on signed languages has occupied an increasingly prominent posi - tion in linguistic theory. It is time for linguists from a broader range of backgrounds to consider the causes, consequences, and appropriate responses to current threats to sign language diversity. In doing so, we must articulate more clearly the value of this diversity to the field of linguistics and the responsibilities the field has toward preserving it.* Keywords : language endangerment, language vitality, language documentation, signed languages 1. Introduction. Concerns about sign language endangerment are not new. Almost immediately after the invention of film, the US National Association of the Deaf began producing films to capture American Sign Language (ASL), motivated by a fear within the deaf community that their language was endangered (Schuchman 2004). -

How Does Social Structure Shape Language Variation? a Case Study of the Kata Kolok Lexicon

HOW DOES SOCIAL STRUCTURE SHAPE LANGUAGE VARIATION? A CASE STUDY OF THE KATA KOLOK LEXICON KATIE MUDD*1, HANNAH LUTZENBERGER2,3, CONNIE DE VOS2, PAULA FIKKERT2, ONNO CRASBORN2, BART DE BOER1 *Corresponding Author: [email protected] 1Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium 2Center of Language Studies, Nijmegen, Netherlands 3International Max Planck Research School, Nijmegen, Netherlands Sign language emergence is an excellent source of data on how language varia- tion is conditioned. Based on the context of sign language emergence, sign lan- guages can be classified as Deaf community sign languages (DCSL), used by a large and dispersed group of mainly deaf individuals (Mitchell & Karchmer, 2004) or as shared sign languages (SSL), which typically emerge in tight-knit communities and are shared by deaf and hearing community members (Kisch, 2008)1. It has been suggested that, in small, tight-knit populations, a higher degree of variation is tolerated than in large, dispersed communities because individuals can remember others’ idiolects (de Vos, 2011; Thompson et al., 2019). Confirm- ing this, Washabaugh (1986) found more lexical variation in Providence Island Sign Language, a SSL, than in American Sign Language (ASL), a DCSL. DC- SLs frequently exhibit variation influenced by schooling patterns, for instance seen in the differences between ages in British Sign Language (Stamp et al., 2014), gender in Irish Sign Language (LeMaster, 2006) and race in ASL (Mc- Caskill et al., 2011). It remains unknown how variation is conditioned in SSLs. The present study of Kata Kolok (KK) is one of the first in-depth studies of how sociolinguistic factors shape lexical variation in a SSL. -

Sign Language Acquisition and Linguistic Theory: Contributions of Brazilian and North-American Researches

REVISTA DA ABRALIN Sign language acquisition and linguistic theory: contributions of Brazilian and North-American researches The conference, given by Prof. Dr. Diane Lillo-Martin (University of Con- necticut), proposed to present the panorama of research on sign language (SL) acquisition, carried out in cooperation between North American and Brazilian researchers. The main objective was to reflect on how investiga- tions in the field of SL acquisition show details concerning linguistic uni- versals, in order to contribute to hypotheses and theories that are tradi- tionally followed in previous studies about oral languages (OL). Topics of interest to the areas of psycholinguistics and studies in language acquisi- tion were ad-dressed, such as structural issues of SL – specifically about American Sign Language (ASL) and Brazilian Sign Language (Libras); effects of visual-spatial modality, the specificity of the process of language acqui- sition by bimodal bilingual deaf children and the implications of linguistic deprivation. A conferência ministrada pela Prof.ª Dr.ª Diane Lillo-Martin (University of Connecticut) propôs-se à apresentação do panorama de pesquisas sobre aquisição de línguas de sinais (doravante LS), realizadas em cooperação entre pesquisadores norte-americanos e brasileiros. Teve como intuito REVISTA DA ABRALIN maior a reflexão de como investigações no domínio da aquisição de LS evi- denciam pormenores atrelados a universais linguísticos, de modo a contri- buir a hipóteses e teorias já difundidas em estudos anteriores com línguas orais (doravante LO). Em vista disso, abordaram-se tópicos de interesse às áreas de psicolinguística e estudos em aquisição de línguas, tais como questões estruturais das LS, especificamente de American Sign Language (ASL) e Língua Brasileira de Sinais (Libras); efeitos de modalidade visuo-es- pacial, especificidade do processo de aquisição de linguagem por crianças surdas bilíngues bimodais e implicaturas de privação linguística. -

CENDEP WP-01-2021 Deaf Refugees Critical Review-Kate Mcauliff

CENDEP Working Paper Series No 01-2021 Deaf Refugees: A critical review of the current literature Kate McAuliff Centre for Development and Emergency Practice Oxford Brookes University The CENDEP working paper series intends to present work in progress, preliminary research findings of research, reviews of literature and theoretical and methodological reflections relevant to the fields of development and emergency practice. The views expressed in the paper are only those of the independent author who retains the copyright. Comments on the papers are welcome and should be directed to the author. Author: Kate McAuliff Institutional address (of the Author): CENDEP, Oxford Brookes University Author’s email address: [email protected] Doi: https://doi.org/10.24384/cendep.WP-01-2021 Date of publication: April 2021 Centre for Development and Emergency Practice (CENDEP) School of Architecture Oxford Brookes University Oxford [email protected] © 2021 The Author(s). This open access article is distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-No Derivative Works (CC BY-NC-ND) 4.0 License. Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2. Deaf Refugee Agency & Double Displacement ............................................................................. -

What Sign Language Creation Teaches Us About Language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3

Focus Article What sign language creation teaches us about language Diane Brentari1∗ and Marie Coppola2,3 How do languages emerge? What are the necessary ingredients and circumstances that permit new languages to form? Various researchers within the disciplines of primatology, anthropology, psychology, and linguistics have offered different answers to this question depending on their perspective. Language acquisition, language evolution, primate communication, and the study of spoken varieties of pidgin and creoles address these issues, but in this article we describe a relatively new and important area that contributes to our understanding of language creation and emergence. Three types of communication systems that use the hands and body to communicate will be the focus of this article: gesture, homesign systems, and sign languages. The focus of this article is to explain why mapping the path from gesture to homesign to sign language has become an important research topic for understanding language emergence, not only for the field of sign languages, but also for language in general. © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. How to cite this article: WIREs Cogn Sci 2012. doi: 10.1002/wcs.1212 INTRODUCTION linguistic community, a language model, and a 21st century mind/brain that well-equip the child for this esearchers in a variety of disciplines offer task. When the very first languages were created different, mostly partial, answers to the question, R the social and physiological conditions were very ‘What are the stages of language creation?’ Language different. Spoken language pidgin varieties can also creation can refer to any number of phylogenic and shed some light on the question of language creation. -

ABSTRACT Hearing Humanities: a Holistic Approach to Audiology

ABSTRACT Hearing Humanities: A Holistic Approach to Audiology Education Callie M. Boren Director: Jason Whitt, Ph.D. This thesis explores the intersection of Deaf/disability identity and the practice of audiology, and has three aims: first, to establish broad background information about the common cultures, identities, and models that relate to disability; second, to connect this background information to the personal and social domains of the lives of people with hearing loss; and finally, to establish current problems and provide direction in training future audiologists in order to ensure clinicians provide care that is above and beyond minimum ethical standards. The first aim will be accomplished by outlining the history and development of Deaf culture and its key features, framing the parallel history and development of disability culture and identity, and comparing and contrasting Deaf culture and identity with disability culture and identity. The second aim of this work will be accomplished by revisiting the definition of disability models, introducing the models that might have bearing on the lives of people with disabilities, and applying these models to the social experience of a person with hearing loss. The final aim of this work will be accomplished by establishing a brief history of the field of audiology, examining the ethics that guide audiology practice, defining and describing audiological counseling, and introducing a new approach to training clinicians that incorporates the humanities. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS: ______________________________________________________ Dr. Jason Whitt, Honors Program APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ______________________________________________________ Dr. Andrew Wisely, Interim Director DATE: _____________________________ HEARING HUMANITIES: A HOLISTIC APPROACH TO AUDIOLOGY EDUCATION A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Callie Michelle Boren Waco, Texas April 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication. -

An Evaluation of Real-Time Requirements for Automatic Sign Language Recognition Using Anns and Hmms - the LIBRAS Use Case

14 SBC Journal on 3D Interactive Systems, volume 4, number 1, 2013 An evaluation of real-time requirements for automatic sign language recognition using ANNs and HMMs - The LIBRAS use case Mauro dos Santos Anjo, Ednaldo Brigante Pizzolato, Sebastian Feuerstack Computer Science and Engineering Department Universidade Federal de Sao˜ Carlos - UFSCar Sao˜ Carlos - SP (Brazil) Emails: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Sign languages are the natural way Deafs use to hands in front of the body with or without movements communicate with other people. They have their own formal and with or without touching other body’s parts. Besides semantic definitions and syntactic rules and are composed by all the hand and face movements, it is also important to a large set of gestures involving hands and head. Automatic recognition of sign languages (ARSL) tries to recognize the notice that face expressions contribute to the meaning signs and translate them into a written language. ARSL is of the communication. They may represent, for instance, a challenging task as it involves background segmentation, an exclamation or interrogation mark. As sign languages hands and head posture modeling, recognition and tracking, are very different from spoken languages and it is hard temporal analysis and syntactic and semantic interpretation. to learn them, it is natural, therefore, to expect computer Moreover, when real-time requirements are considered, this task becomes even more challenging. In this paper, we systems to capture gestures to understand what someone present a study of real time requirements of automatic sign is feeling or trying to communicate with a specific sign language recognition of small sets of static and dynamic language in order to promote social inclusion. -

Sign Language Ideologies: Practices and Politics

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Heriot Watt Pure Annelies Kusters, Mara Green, Erin Moriarty and Kristin Snoddon Sign language ideologies: Practices and politics While much research has taken place on language attitudes and ideologies regarding spoken languages, research that investigates sign language ideol- ogies and names them as such is only just emerging. Actually, earlier work in Deaf Studies and sign language research uncovered the existence and power of language ideologies without explicitly using this term. However, it is only quite recently that scholars have begun to explicitly focus on sign language ideologies, conceptualized as such, as a field of study. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first edited volume to do so. Influenced by our backgrounds in anthropology and applied linguistics, in this volume we bring together research that addresses sign language ideologies in practice. In other words, this book highlights the importance of examining language ideologies as they unfold on the ground, undergirded by the premise that what we think that language can do (ideology) is related to what we do with language (practice).¹ All the chapters address the tangled confluence of sign lan- guage ideologies as they influence, manifest in, and are challenged by commu- nicative practices. Contextual analysis shows that language ideologies are often situation-dependent and indeed often seemingly contradictory, varying across space and moments in time. Therefore, rather than only identifying language ideologies as they appear in metalinguistic discourses, the authors in this book analyse how everyday language practices implicitly or explicitly involve ideas about those practices and the other way around.