Loss, Memory and Cultural Identity in the Dominion of Newfoundland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

Ward Their Work As a Consequence of This Wider Conception of Social Service

676 LEGISLATION AND PRINCIPAL EVENTS ward their work as a consequence of this wider conception of social service. Charity has been so organized as to aim at the prevention rather" than the mere palliation of destitution. Hospital authorities, too, have been convinced that prevention is better than cure, and have organized out-patient departments for the dissemination of medical information and assistance among the poorer classes. The great prob lems of feeble-mindedness and venereal disease have also been courageously attacked, and considerable progress has been made in arousing the public mind and conscience to the greatness of the dangers resulting from these scourges of humanity. All these activities above described have led to an active demand for the services of trained social workers. The universities were called upon to supply such workers, and in 1914 the University of Toronto opened its Department of Social Service, the first institution in Canada to pro vide regular academic training for social workers. The success of this venture led to the establishment of similar departments in other Canadian universities, notably McGill and the University of Montreal, while Queen's, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba Universities have offered part time courses or special lectures on topics of social service. To co-ordinate the social activities of the agencies above de scribed, the Social Service Council of Canada was established in 1907. It consists of a federal union of eighteen Dominion-wide bodies and nine provincial Social Service -

00 Toc-Contributors.Qxd

00131-05 Lambert Article_Layout 2012-10-30 8:17 PM Page 89 No Choice But to Look Elsewhere: Attracting Immigrants to Newfoundland, 1840-1890 CAROLYN LAMBERT Au 19 e siècle, Terre-Neuve était entraînée dans la marche de l’Amérique du Nord vers le progrès. À compter des années 1840, le désir de mettre en valeur l’intérieur du territoire était présent dans le discours de ses politiciens, selon qui la diversification économique – en particulier le développement de l’agriculture – libérerait la population de sa dépendance envers les ressources côtières. Incapables d’amener les pêcheurs à se tourner vers l’agriculture, les autorités publiques en vinrent à croire qu’elles devraient trouver ailleurs les individus qui permettraient à Terre-Neuve d’aller de l’avant. Conscients qu’une immigration à grande échelle était impossible à cause des contraintes géographiques, les contemporains fondaient leurs espoirs sur la venue d’un petit nombre d’agronomes qualifiés des îles Britanniques. Cependant, aucun gouvernement ne formula une politique officielle d’immigration, et les stratégies d’immigration proposées demeuraient prudentes. Nineteenth-century Newfoundland was caught up in North America’s drive towards progress. The desire for landward development was present within political discourse from the 1840s onwards, politicians arguing that economic diversification – particularly agricultural development – would free the population from coastal resource dependency. Failure to entice fishermen to farm led officials to believe that individuals to push Newfoundland forward would have to be found elsewhere. Contemporaries were aware of the geographic limitations preventing large-scale immigration, and hoped for a small number of skilled agriculturalists from the British Isles. -

Sovereign Debt Guarantees and Default: Lessons from the UK and Ireland, 1920-1938∗

Sovereign debt guarantees and default: Lessons from the UK and Ireland, 1920-1938∗ Nathan Foley-Fisher y Eoin McLaughlin z This draft: May 2016; First draft: March 2014 Abstract We study the daily yields on Irish land bonds listed on the Dublin Stock Exchange during the years 1920-1938. We exploit Irish events during the period and structural differences in land bonds to tease out a measure of investors’ credibility in a UK sovereign guarantee. Using Ireland’s default on intergovernmental payments in 1932, we find a premium of about 43 basis points associated with uncertainty about the UK government guarantee. We discuss the economic and political forces behind the Irish and UK governments’ decisions pertaining to the default. Our finding has implications for modern-day proposals to issue jointly- guaranteed sovereign debt. ‘Further, in view of all the historical circumstances, it is not equitable that the Irish people should be obliged to pay away these moneys’ - Eamon De Valera, 12 October 1932 Keywords: Irish land bonds, Dublin Stock Exchange, sovereign default, debt guarantees. JEL Classification: N23, N24, G15 ∗We gratefully acknowledge discussion and comments from Stijn Claessens, Chris Colvin, David Greasley, Aidan Kane, John McDonagh, Ralf Meisenzahl, Kris Mitchener, Cormac Ó Gráda, Kim Oosterlinck, Kevin O’Rourke, Rodney Ramcharan, Paul Sharp, Christoph Trebesch, John Turner, and seminar participants in the European Historical Economics Society Annual Meetings 2015, Atlanta Fed/Emory University Workshop on Monetary and Financial History 2015, Central Bank of Ireland Economic History Workshop 2015, Irish Quantitative History Conference 2014, the Economic History Society Annual Conference 2014, the Cliometrics Conference 2014, the Scottish Economic Society Annual Conference 2014, Swiss National Bank, Dundee, Queen’s University Centre for Economic History, University of Edinburgh, LSE, and the Federal Reserve Board. -

Legion of Frontiersmen Notebook

Legion of Frontiersmen Notebook Includes over 30 pages with maps, charts, images and about 300 referenced historical entries Part I - General Information Part II - Referenced Timeline Part III - Uniform and Accoutrements ©Barry William Shandro M.Ed – Edmonton Canada – 01 January 2017 1 Foreword This is a personal notebook. Hopefully, this cache of information from a Canadian perspective assists with understanding the enigmatic Legion of Frontiersmen. This document is not intended for commercial reproduction nor is it intended for sale; however, the reader is most welcome to use this information as a starting point for further research. Please credit the original sources of information noted. Four decades ago I began to hear stories about the Legion of Frontiersmen from First and Second World War veterans. These accounts seemed questionable so I began a long process of investigating these claims and looking for informative sources. – To my surprise much of the verbal lore was confirmed with news quotations, documents, photos or addressed in rediscovered Frontiersmen publications. Concurrent to my efforts, the members of the History and Archives Section, Legion of Frontiersmen [Countess Mountbatten’s Own] willingly discussed their respective efforts to rediscover and preserve a very unique piece of Imperial history. Spearheaded by the Legion Historian, Geoffrey A. Pocock [Outrider of Empire, University of Alberta Press] a great deal of material has been placed online - see The Frontiersmen Historian. Additionally, the University of Alberta has been most helpful as the repository of Legion of Frontiersmen related documents. Finally, the grammatical errors and technical writing irregularities have been inserted to see if you are paying attention. -

Adams, John Joseph

Private John Joseph Adams (Number 716001) of the 87th Battalion (Canadian Grenadier Guards), Canadian Expeditionary Force, is buried in Écoivres Military Cemetery, Mont St-Éloi: Grave reference III. K. 4.. (Right: The image of the Canadian Grenadier Guards cap badge – and of its British counterpart – is from the Regimental Rogue web- site.) (continued) 1 His occupations prior to military service recorded as those of both labourer and shoe- maker, John Joseph Adams appears to have left behind him no indication in his files of his departure from Harbour Grace in the Dominion of Newfoundland to Sydney, Cape Breton, in the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, in March 1916 this his recorded place of residence. However, it was in the town of Truro that John Joseph Adams enlisted on March 16 of 1916, two days before presenting himself for medical examination*. On the day of his enlistment he was attached to the 106th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force (Nova Scotia Rifles) which was based in Truro and, twelve days later, underwent the formality of being… finally approved and inspected by the officer commanding the unit, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Innes. *Somewhat curiously, his original attestation papers are dated May 29, some two months later. This is surely an error… The following four months were to be spent in training in Truro* – although a private diary of one of the recruits records that… no barracks, parade ground or firing range, the men were living in hotels, the YMCA, or at home… training consisted mainly of shovelling snow and marching. *Two further companies were based in Pictou and Springhill. -

Application of Link Integrity Techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON Faculty of Engineering and Applied Science Department of Electronics and Computer Science A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD Supervisor: Prof. Wendy Hall and Dr Les Carr Examiner: Dr Nick Gibbins Application of Link Integrity techniques from Hypermedia to the Semantic Web by Rob Vesse February 10, 2011 UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHAMPTON ABSTRACT FACULTY OF ENGINEERING AND APPLIED SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF ELECTRONICS AND COMPUTER SCIENCE A mini-thesis submitted for transfer from MPhil to PhD by Rob Vesse As the Web of Linked Data expands it will become increasingly important to preserve data and links such that the data remains available and usable. In this work I present a method for locating linked data to preserve which functions even when the URI the user wishes to preserve does not resolve (i.e. is broken/not RDF) and an application for monitoring and preserving the data. This work is based upon the principle of adapting ideas from hypermedia link integrity in order to apply them to the Semantic Web. Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Hypothesis . .2 1.2 Report Overview . .8 2 Literature Review 9 2.1 Problems in Link Integrity . .9 2.1.1 The `Dangling-Link' Problem . .9 2.1.2 The Editing Problem . 10 2.1.3 URI Identity & Meaning . 10 2.1.4 The Coreference Problem . 11 2.2 Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1 Early Hypermedia . 11 2.2.1.1 Halasz's 7 Issues . 12 2.2.2 Open Hypermedia . 14 2.2.2.1 Dexter Model . 14 2.2.3 The World Wide Web . -

Uncharted Waters: Has the Cook Islands Become Eligible for Membership in the United Nations?

169 UNCHARTED WATERS: HAS THE COOK ISLANDS BECOME ELIGIBLE FOR MEMBERSHIP IN THE UNITED NATIONS? Stephen Eliot Smith* The paper gives in depth considerationto whether the Cook Islands could become a member of the United Nations. The authorconcludes that a Cook Islands applicationfor UN membership would be successful, and undoubtedly UN membership would provide advantagesfor the Cook Islands and its residents. Whether it will become a reality is a political decision that is one aspect of what it means for a State and its people to exercise the treasured right to self-determination. As such, it is a decision that rests solely with the government andpeople ofthe Cook Islands. I Introduction Jonah, my eight-year-old son, is interested in geography. On the wall of his bedroom we have hung a large and detailed political map of the world. Recently, he had been examining the area of the South Pacific, and we had a conversation that went something like this: Jonah: "Dad, are the Cook Islands part of New Zealand?" Me: "No, not really... " Jonah: "On the map under 'Cook Islands' it says 'NZ' in tiny red letters." Me: "Yes, New Zealand and the Cook Islands are good friends, and we share a lot of the same things Jonah: "So New Zealand owns the Cook Islands, right?" Me: "No, we don't own it, but we've agreed to be partners, and..." Jonah: "Did we conquer them in battle?" Me: "No, but... " And so it went, with me providing unsatisfying answers that ultimately were summed up in the classic parental escape-hatch: "it's complicated". -

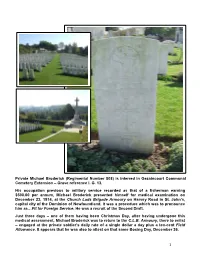

1 Private Michael Broderick

Private Michael Broderick (Regimental Number 808) is interred in Gezaincourt Communal Cemetery Extension – Grave reference I. G. 13. His occupation previous to military service recorded as that of a fisherman earning $500.00 per annum, Michael Broderick presented himself for medical examination on December 23, 1914, at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury on Harvey Road in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland. It was a procedure which was to pronounce him as…Fit for Foreign Service. He was a recruit of the Second Draft. Just three days – one of them having been Christmas Day, after having undergone this medical assessment, Michael Broderick was to return to the C.L.B. Armoury, there to enlist – engaged at the private soldier’s daily rate of a single dollar a day plus a ten-cent Field Allowance. It appears that he was also to attest on that same Boxing Day, December 26. 1 While those recruits of the Second Draft and resident in St. John’s were to spend the next number of weeks at home, often continuing, at least temporarily, to work, those from further afield were often lodged in the city, the expenses coming from the Public Purse. Private Broderick, Number 808, from St. Brendan’s, was apparently to stay at the home of Mr. and Mrs. P. Murphy – were they his aunt and uncle? - on Long’s Hill, although how he was to occupy himself during those six weeks is not to be found among his papers. On the fourth day of February of 1915, the first re- enforcements – this was ‘C’ Company - for the Newfoundland contingent – it was not yet at battalion strength - which by this time was serving in Scotland (see further below), were to embark via the sealing tender Neptune onto the SS Dominion – the vessel having anchored to the south of St. -

Island Studies Journal, Vol. 9, No. 1, 2014, Pp. 103-122 the Role of The

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 9, No. 1, 2014, pp. 103-122 The role of the political system in shaping island nationalism: a case-study examination of Puerto Rico and Newfoundland. Valérie Vézina PhD candidate, Université du Québec à Montréal Canada [email protected] ABSTRACT: Islands are sites where specific forms of governance can develop, providing insights for ‘continental’ nations. This paper discusses the role the political system has in shaping nationalist policies and demands in island settings, examining the specific cases of Puerto Rico and Newfoundland. Starting from a hypothesis outlined by both Fazi and Hepburn, this paper aims at finding empirical data and evidence to the hypothesis that island jurisdictions having a different party system than their central state show an increase in their nationalist demands. In order to do so, this paper first examines the definition of island nationalism and offers, following Lluch’s typology, a framework for analyzing nationalist demands. Then, it examines important historical material in both Newfoundland and Puerto Rico. This will demonstrate how political parties and political leaders can use nationalism to shape policies and will allow us to verify the initial hypothesis. Keywords: islands; nationalism; Newfoundland; political leaders; political parties; political system; Puerto Rico © 2014 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. Introduction Islands have been studied and celebrated in literature, biology, anthropology and politics for many years; and the study of the relationship between islandness and nationalism goes back at least to the musings of Rousseau (1765) on Corsica. In the study of island nationalism in particular, there is some agreement that some key circumstances can enhance nationalist sentiments, be they economic, geographical or political. -

The Newfoundland-Canada Relationship Through the Lens of Legal History: Imitation, Influence, Or Indifference?

Osgoode Hall Law School of York University Osgoode Digital Commons Articles & Book Chapters Faculty Scholarship 2017 The Newfoundland-Canada Relationship Through the Lens of Legal History: Imitation, Influence, or Indifference? Philip Girard Osgoode Hall Law School of York University, [email protected] Source Publication: Melvin Baker, Christopher Curran and J. Derek Green, eds., Discourse and Discovery: Sir Richard Whitbourne Quatercentennial Symposium 1615-2015 (St. John’s NL: Law Society of Newfoundland and Labrador, 2016), 317-27 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works Part of the Law Commons Repository Citation Girard, Philip, "The Newfoundland-Canada Relationship Through the Lens of Legal History: Imitation, Influence, or Indifference?" (2017). Articles & Book Chapters. 2622. https://digitalcommons.osgoode.yorku.ca/scholarly_works/2622 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Osgoode Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Articles & Book Chapters by an authorized administrator of Osgoode Digital Commons. Discourse and Discovery The Newfoundland-Canada Relationship Through the Lens of Legal History: Imitation, Influence, or Indifference? Philip Girard Newfoundland legal history has tended to focus on the period prior to the achieve- ment of representative government in 1832 and the existing literature dealing with more recent times is somewhat sporadic.1 Nor is there yet any comprehensive overview of Canadian legal history. This makes any effort to consider links between the two some- what premature and necessarily impressionistic. Thus this paper will focus on the atti- tude of Newfoundland’s legal community towards the law of Canada as revealed in judicial decisions, legislation, and trends within the legal profession, from 1869, when the Newfoundland electorate soundly rejected Confederation with Canada, until a decade or two after it eventually accepted union with Canada in 1949. -

Seventh-Day Adventist Denomination

Seventh-day Adventist Denomination The Official Directories 1940 Published by the REVIEW £6 HERALD PUBLISHING ASSOCIATION TAKOMA PARK, WASHINGTON, D. C. PRINTED IN THE U. S. A. T 1C lf 44444.44+4.4.444.4X4444444.4.4.44444.44+44++++++++++ + 4. 4. .4. 4. S. D. A. +.4 $ + * + THEOLOGICAL + .2. SEMINARY 4. + +. ++.÷ • • +. PURPOSE .4 .... 4. It is the purpose of this school to provide 4 + opportunity for such graduate study and research as will contribute to the advancement of sound 4 • scholarship in the fields of Bible and Religious +4 + History in harmony with the educational principles + of the Seventh-day Adventist denomination, and to + + provide instruction in the practical application of +..: * its program of study. + + ,1 For the attainment of this purpose the + curriculum is so organized as to make available + t courses in the various fields of theological study, ,T. such as Biblical Languages, Archaeology, Exegesis, + and Doctrinal and Pastoral Theology; in Religious + History, including Near Eastern Antiquity, Church + History, and Non-Christian Religions; in Homi- letics, Speech, and such other related courses as + from time to time may be deemed necessary by its faculty and board of directors. 4.- + •:. 0 f special interest to conference executives + is a class recently organized in Conference Admin- + istration. • + Information -+ + For information and application blanks, write to— + + ,,.. + ..;,..„ .t. M. E. KERN, President Takoma Park, Washington, D.C. 4 4 + * +++++++++++++0-044+.4+0' ++.4.*-0404,'Ax++++4•+++++++4•44+++ 1940 YEAR BOOK OF THE SEVENTH-DAY ADVENTIST DENOMINATION Comprising a Complete Directory of the General Conference, all Union and Local Conferences, Mission Fields, Educational Institutions, Publishing Houses, Periodicals, and Sanitariums.