Maritime Support for Great Britain's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antarctic Peninsula

Hucke-Gaete, R, Torres, D. & Vallejos, V. 1997c. Entanglement of Antarctic fur seals, Arctocephalus gazella, by marine debris at Cape Shirreff and San Telmo Islets, Livingston Island, Antarctica: 1998-1997. Serie Científica Instituto Antártico Chileno 47: 123-135. Hucke-Gaete, R., Osman, L.P., Moreno, C.A. & Torres, D. 2004. Examining natural population growth from near extinction: the case of the Antarctic fur seal at the South Shetlands, Antarctica. Polar Biology 27 (5): 304–311 Huckstadt, L., Costa, D. P., McDonald, B. I., Tremblay, Y., Crocker, D. E., Goebel, M. E. & Fedak, M. E. 2006. Habitat Selection and Foraging Behavior of Southern Elephant Seals in the Western Antarctic Peninsula. American Geophysical Union, Fall Meeting 2006, abstract #OS33A-1684. INACH (Instituto Antártico Chileno) 2010. Chilean Antarctic Program of Scientific Research 2009-2010. Chilean Antarctic Institute Research Projects Department. Santiago, Chile. Kawaguchi, S., Nicol, S., Taki, K. & Naganobu, M. 2006. Fishing ground selection in the Antarctic krill fishery: Trends in patterns across years, seasons and nations. CCAMLR Science, 13: 117–141. Krause, D. J., Goebel, M. E., Marshall, G. J., & Abernathy, K. (2015). Novel foraging strategies observed in a growing leopard seal (Hydrurga leptonyx) population at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Animal Biotelemetry, 3:24. Krause, D.J., Goebel, M.E., Marshall. G.J. & Abernathy, K. In Press. Summer diving and haul-out behavior of leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) near mesopredator breeding colonies at Livingston Island, Antarctic Peninsula. Marine Mammal Science.Leppe, M., Fernandoy, F., Palma-Heldt, S. & Moisan, P 2004. Flora mesozoica en los depósitos morrénicos de cabo Shirreff, isla Livingston, Shetland del Sur, Península Antártica, in Actas del 10º Congreso Geológico Chileno. -

2. Disc Resources

An early map of the world Resource D1 A map of the world drawn in 1570 shows ‘Terra Australis Nondum Cognita’ (the unknown south land). National Library of Australia Expeditions to Antarctica 1770 –1830 and 1910 –1913 Resource D2 Voyages to Antarctica 1770–1830 1772–75 1819–20 1820–21 Cook (Britain) Bransfield (Britain) Palmer (United States) ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ ▼ Resolution and Adventure Williams Hero 1819 1819–21 1820–21 Smith (Britain) ▼ Bellingshausen (Russia) Davis (United States) ▼ ▼ ▼ Williams Vostok and Mirnyi Cecilia 1822–24 Weddell (Britain) ▼ Jane and Beaufoy 1830–32 Biscoe (Britain) ★ ▼ Tula and Lively South Pole expeditions 1910–13 1910–12 1910–13 Amundsen (Norway) Scott (Britain) sledge ▼ ▼ ship ▼ Source: Both maps American Geographical Society Source: Major voyages to Antarctica during the 19th century Resource D3 Voyage leader Date Nationality Ships Most southerly Achievements latitude reached Bellingshausen 1819–21 Russian Vostok and Mirnyi 69˚53’S Circumnavigated Antarctica. Discovered Peter Iøy and Alexander Island. Charted the coast round South Georgia, the South Shetland Islands and the South Sandwich Islands. Made the earliest sighting of the Antarctic continent. Dumont d’Urville 1837–40 French Astrolabe and Zeelée 66°S Discovered Terre Adélie in 1840. The expedition made extensive natural history collections. Wilkes 1838–42 United States Vincennes and Followed the edge of the East Antarctic pack ice for 2400 km, 6 other vessels confirming the existence of the Antarctic continent. Ross 1839–43 British Erebus and Terror 78°17’S Discovered the Transantarctic Mountains, Ross Ice Shelf, Ross Island and the volcanoes Erebus and Terror. The expedition made comprehensive magnetic measurements and natural history collections. -

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

Antarctic Primer

Antarctic Primer By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller By Nigel Sitwell, Tom Ritchie & Gary Miller Designed by: Olivia Young, Aurora Expeditions October 2018 Cover image © I.Tortosa Morgan Suite 12, Level 2 35 Buckingham Street Surry Hills, Sydney NSW 2010, Australia To anyone who goes to the Antarctic, there is a tremendous appeal, an unparalleled combination of grandeur, beauty, vastness, loneliness, and malevolence —all of which sound terribly melodramatic — but which truly convey the actual feeling of Antarctica. Where else in the world are all of these descriptions really true? —Captain T.L.M. Sunter, ‘The Antarctic Century Newsletter ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 3 CONTENTS I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Guidance for Visitors to the Antarctic Antarctica’s Historic Heritage South Georgia Biosecurity II. THE PHYSICAL ENVIRONMENT Antarctica The Southern Ocean The Continent Climate Atmospheric Phenomena The Ozone Hole Climate Change Sea Ice The Antarctic Ice Cap Icebergs A Short Glossary of Ice Terms III. THE BIOLOGICAL ENVIRONMENT Life in Antarctica Adapting to the Cold The Kingdom of Krill IV. THE WILDLIFE Antarctic Squids Antarctic Fishes Antarctic Birds Antarctic Seals Antarctic Whales 4 AURORA EXPEDITIONS | Pioneering expedition travel to the heart of nature. CONTENTS V. EXPLORERS AND SCIENTISTS The Exploration of Antarctica The Antarctic Treaty VI. PLACES YOU MAY VISIT South Shetland Islands Antarctic Peninsula Weddell Sea South Orkney Islands South Georgia The Falkland Islands South Sandwich Islands The Historic Ross Sea Sector Commonwealth Bay VII. FURTHER READING VIII. WILDLIFE CHECKLISTS ANTARCTIC PRIMER 2018 | 5 Adélie penguins in the Antarctic Peninsula I. CONSERVING ANTARCTICA Antarctica is the largest wilderness area on earth, a place that must be preserved in its present, virtually pristine state. -

Geochronology, Geochemistry and Mineralogy

293 THE PLUTONIC ROCKS OF THE SOUTHERN GERLACHE STRAIT, ANTARCTICA: GEOCHRONOLOGY, GEOCHEMISTRY AND MINERALOGY Parada Qki Jem SapWe”, Ada Rlcanb’. Guerm Rslsp. Muniiaga Francisco*. Berg Karstan’. l Cepartamenb da Geokafa Y Geoffsiy Unkersided da Chib. Casitfa 13518, cons0 21, Sawlago. Chite. ‘* Maratofre 6 GaobgfPekobgfe. FacutaOdes Scbnma et Techniques. 23. rue du Docteur Paul Mbhebn ,4023 .%it Elienrm. tXdex, Frano. Reaumen Las mcas ptut6nk.a~estudiadas se cam&&an por una dsminu&n hwia el 0~s.~ ds tar adadas (Cretktm inferic+ Mibcw~~). Gaoqlmicamen te son simiiares am-qua sn tos granitofdes CretAdt se datecta una ten&n& de aumentar at StO, hacfa et es% Esknaknes de h pmfunddad & la hmnti y da mphmmienb rugiers VI aumentc hada et oesw. Key wor&: F%Jtism, An- geochmrmfogy. gecdwmtsby. Introduction The inbusi~ rocks of the G&ache Strait induda gabrros. diirites. tonafites. granodiirites and granites (Akro5n et at. 1976). which form part01 the extensiw plutonism developed in Ihe Antarctic Peninsula as a pmductof a continwus subducbn since Early Mesozoic to Lals Tertiary (cf. Parkhurst 1962). Prevfour studier dstinguished pru and post-vokanic rocks ptutons (West, 1974) and reported radiietric eges that indicate Cretaceous ages for the Dance Coast rocks and Tertiary ages for the Wrenke Is. andSouthern Anversls. (Scott, 1965; Par&hunt, 1482: British AntucScSurvey. 1964). Thusaweshvarddecreasing ages of tie pfulonio mdts is insinuated. The aim of this study is to get a better undarstandrg of the poorly known plutonic history of tie Geriache Strait, based ongeochronotogical. ge~emicalandmineralogicaldalaofalimitednumberof samples. ThisstudywastinmcedbythetNACH grant 8.17, and is a conbibu%n to the IGCP Profact 249 ‘An&m Msgmatism’. -

American Eel Anguilla Rostrata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge V. Tremblay, D.K. Cairns, F. Caron, J.M. Casselman, and N.E. Mandrak for writing the status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair (Freshwater Fishes) COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. Funding for this report was provided by Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’anguille d'Amérique (Anguilla rostrata) au Canada. Cover illustration: American eel — (Lesueur 1817). From Scott and Crossman (1973) by permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/458-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43225-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name American eel Scientific name Anguilla rostrata Status Special Concern Reason for designation Indicators of the status of the total Canadian component of this species are not available. -

Federal Register/Vol. 84, No. 78/Tuesday, April 23, 2019/Rules

Federal Register / Vol. 84, No. 78 / Tuesday, April 23, 2019 / Rules and Regulations 16791 U.S.C. 3501 et seq., nor does it require Agricultural commodities, Pesticides SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: The any special considerations under and pests, Reporting and recordkeeping Antarctic Conservation Act of 1978, as Executive Order 12898, entitled requirements. amended (‘‘ACA’’) (16 U.S.C. 2401, et ‘‘Federal Actions to Address Dated: April 12, 2019. seq.) implements the Protocol on Environmental Justice in Minority Environmental Protection to the Richard P. Keigwin, Jr., Populations and Low-Income Antarctic Treaty (‘‘the Protocol’’). Populations’’ (59 FR 7629, February 16, Director, Office of Pesticide Programs. Annex V contains provisions for the 1994). Therefore, 40 CFR chapter I is protection of specially designated areas Since tolerances and exemptions that amended as follows: specially managed areas and historic are established on the basis of a petition sites and monuments. Section 2405 of under FFDCA section 408(d), such as PART 180—[AMENDED] title 16 of the ACA directs the Director the tolerance exemption in this action, of the National Science Foundation to ■ do not require the issuance of a 1. The authority citation for part 180 issue such regulations as are necessary proposed rule, the requirements of the continues to read as follows: and appropriate to implement Annex V Regulatory Flexibility Act (5 U.S.C. 601 Authority: 21 U.S.C. 321(q), 346a and 371. to the Protocol. et seq.) do not apply. ■ 2. Add § 180.1365 to subpart D to read The Antarctic Treaty Parties, which This action directly regulates growers, as follows: includes the United States, periodically food processors, food handlers, and food adopt measures to establish, consolidate retailers, not States or tribes. -

Aboriginal Rights and the Canadian Constitution, by Michael Asch

REVIEWS 157 DR JOHN RAE. By R.L. RICHARDS. Whitby: Caedmon of Whitby (9 The sixmaps are helpful, but they omit a few of the important place John Street, Whitby, England YO21 3ET), 1985.231 p. +6 maps, namesmentioned in the text. An additionaloverall map of the 31 illus., bib., index. f16.50. Franklii search expeditions would have been helpful. Richards made animportant geographical error on page 44: Theone-mile-wide John Rae was one of the most successful arctic explorers. His four isthmus seen byRae joined the Ross Peninsula, not the Penin- majorexpeditions mapped, by his reckoning, 1765 miles of pre- Boothia viously unknown arctic coastline. He proved that Boothia was a penin-sula as stated. I would have liked more detailed references in the names sula and that King William Land was an island. He was the first to already numerous footnotes, indexing of important that appear only in footnotes, and a list of the maps and illustrations. Richards obtain definitive evidence regarding the fate of the third Franklin fails to mention that modern Canadian maps and the officialGazeteer exetion. give inadequate credit to Rae, sometimes giving his names to the Rae was prepared for his later achievements by his childhood in thewrong localities and misspelling Locker for LockyerWdbank and for Orkneys and by ten years with the Hudson’s Bay Company at MooseWelbank. One of Rae’s presentations to the British Association has Factory. Of his Orkney activities Rae later said: been omitted. In a few places it would have been helpfulto have given By the time I was fifteen, I had become so seasoned as to care little modern names of birds and mammals (Rae’s “deer” are of course about cold or wet, had acquired a fair knowledge of boating, was a caribou). -

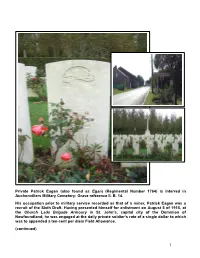

Private Patrick Eagan (Also Found As Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) Is Interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave Reference II

Private Patrick Eagan (also found as Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) is interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave reference II. B. 14. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a miner, Patrick Eagan was a recruit of the Sixth Draft. Having presented himself for enlistment on August 5 of 1915, at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland, he was engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. (continued) 1 Just one day after having enlisted, on August 6 he was to return to the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road. On this second occasion Patrick Eagan was to undergo a medical examination, a procedure which was to pronounce him as being…Fit for Foreign Service. And it must have been only hours afterwards again that there then came the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. On the same August 6 he pledged his allegiance to the reigning monarch, George V, at which moment Patrick Eagan thus became…a soldier of the King. A further, and lengthier, waiting-period was now in store for the recruits of this draft, designated as ‘G’ Company, before they were to depart from Newfoundland for…overseas service. Private Eagan, Regimental Number 1764, was not to be again called upon until October 27, after a period of twelve weeks less two days. Where he was to spend this intervening time appears not to have been recorded although he possibly returned temporarily to his work and perhaps would have been able to spend time with family and friends in the Bonavista Bay community of Keels – but, of course, this is only speculation. -

The Centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’S Enduring Scientific Legacy and Ongoing Presence There”

Debate on 18 October: Scott Expedition to Antarctica and Scientific Legacy This Library Note provides background reading for the debate to be held on Thursday, 18 October: “the centenary of the Scott Expedition to Antarctica and of the United Kingdom’s enduring scientific legacy and ongoing presence there” The Note provides information on Antarctica’s geography and environment; provides a history of its exploration; outlines the international agreements that govern the territory; and summarises international scientific cooperation and the UK’s continuing role and presence. Ian Cruse 15 October 2012 LLN 2012/034 House of Lords Library Notes are compiled for the benefit of Members of the House of Lords and their personal staff, to provide impartial, politically balanced briefing on subjects likely to be of interest to Members of the Lords. Authors are available to discuss the contents of the Notes with the Members and their staff but cannot advise members of the general public. Any comments on Library Notes should be sent to the Head of Research Services, House of Lords Library, London SW1A 0PW or emailed to [email protected]. Table of Contents 1.1 Geophysics of Antarctica ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Environmental Concerns about the Antarctic ......................................................... 2 2.1 Britain’s Early Interest in the Antarctic .................................................................... 4 2.2 Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration ....................................................................... -

American Eel (Anguilla Rostrata )

American Eel (Anguilla rostrata ) Abstract The American eel ( Anguilla rostrata ) is a freshwater eel native in North America. Its smooth, elongated, “snake-like” body is one of the most noted characteristics of this species and the other species in this family. The American Eel is a catadromous fish, exhibiting behavior opposite that of the anadromous river herring and Atlantic salmon. This means that they live primarily in freshwater, but migrate to marine waters to reproduce. Eels are born in the Sargasso Sea and then as larvae and young eels travel upstream into freshwater. When they are fully mature and ready to reproduce, they travel back downstream into the Sargasso Sea,which is located in the Caribbean, east of the Bahamas and north of the West Indies, where they were born (Massie 1998). This species is most common along the Atlantic Coast in North America but its range can sometimes even extend as far as the northern shores of South America (Fahay 1978). Context & Content The American Eel belongs in the order of Anguilliformes and the family Anguillidae, which consist of freshwater eels. The scientific name of this particular species is Anguilla rostrata; “Anguilla” meaning the eel and “rostrata” derived from the word rostratus meaning long-nosed (Ross 2001). General Characteristics The American Eel goes by many common names; some names that are more well-known include: Atlantic eel, black eel, Boston eel, bronze eel, common eel, freshwater eel, glass eel, green eel, little eel, river eel, silver eel, slippery eel, snakefish and yellow eel. Many of these names are derived from the various colorations they have during their lifetime. -

Ward Their Work As a Consequence of This Wider Conception of Social Service

676 LEGISLATION AND PRINCIPAL EVENTS ward their work as a consequence of this wider conception of social service. Charity has been so organized as to aim at the prevention rather" than the mere palliation of destitution. Hospital authorities, too, have been convinced that prevention is better than cure, and have organized out-patient departments for the dissemination of medical information and assistance among the poorer classes. The great prob lems of feeble-mindedness and venereal disease have also been courageously attacked, and considerable progress has been made in arousing the public mind and conscience to the greatness of the dangers resulting from these scourges of humanity. All these activities above described have led to an active demand for the services of trained social workers. The universities were called upon to supply such workers, and in 1914 the University of Toronto opened its Department of Social Service, the first institution in Canada to pro vide regular academic training for social workers. The success of this venture led to the establishment of similar departments in other Canadian universities, notably McGill and the University of Montreal, while Queen's, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba Universities have offered part time courses or special lectures on topics of social service. To co-ordinate the social activities of the agencies above de scribed, the Social Service Council of Canada was established in 1907. It consists of a federal union of eighteen Dominion-wide bodies and nine provincial Social Service