Historical Atlas of the British Empire and Commonwealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Secret Garden Issue July/August 2017

THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 IAM INFINITY #14 July/August 2017 Smiljana Gavrančić (Serbia) - Editor, Founder & Owner Victor Olliver (UK) - Associate from the Astrological Journal of the AA GB Sharon Knight (UK) - Associate from APAI Frank C. Clifford (UK) - Associate from the London School of Astrology Mandi Lockley (UK) - Associate from the Academy of Astrology UK Wendy Stacey (UK) - Associate from the Mayo School of Astrology and the AA GB Jadranka Ćoić (UK) - Associate from the Astrological Lodge of London Tem Tarriktar (USA) – Associate from The Mountain Astrologer magazine Athan J. Zervas (Greece) – Critique Partner/Associate for Art & Design 2 THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 3 THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 The iris means different things to different people and cultures. Some of its most common meanings are: Royalty Faith Wisdom Hope Valor Original photo by: Rudolf Ribarz (Austrian painter) – Irises 4 THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 www.londonschoolofastrology.co.uk 5 THE SECRET GARDEN ISSUE JULY/AUGUST 2017 CONTENTS 7 – IAM EDITOR‘S LETTER: „Destiny‘s Gate―; Electric Axis in Athens by Smiljana Gavrančić 11 – About Us 13 - Mikhail Gorbachev And Uranus Return In 2014; „The Guardian of Europe― by Smiljana Gavrančić 21 - IAM A GUEST: Roy Gillett & Victor Olliver 29 – IAM A GUEST: Nona Voudouri 34 – IAM A GUEST: Anne Whitaker 38 - The Personal is Political by Wendy Stacey 41 - 2017 August Eclipses forecasting by Rod Chang 48 - T – squares: An Introduction by Frank C. Clifford 57 - Astrology – -

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in the Commonwealth

Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites Human Rights, Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity in The Commonwealth: Struggles for Decriminalisation and Change Edited by Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites © Human Rights Consortium, Institute of Commonwealth Studies, School of Advanced Study, University of London, 2013 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NCND 4.0) license. More information regarding CC licenses is available at https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/ Available to download free at http://www.humanities-digital-library.org ISBN 978-1-912250-13-4 (2018 PDF edition) DOI 10.14296/518.9781912250134 Institute of Commonwealth Studies School of Advanced Study University of London Senate House Malet Street London WC1E 7HU Cover image: Activists at Pride in Entebbe, Uganda, August 2012. Photo © D. David Robinson 2013. Photo originally published in The Advocate (8 August 2012) with approval of Sexual Minorities Uganda (SMUG) and Freedom and Roam Uganda (FARUG). Approval renewed here from SMUG and FARUG, and PRIDE founder Kasha Jacqueline Nabagesera. Published with direct informed consent of the main pictured activist. Contents Abbreviations vii Contributors xi 1 Human rights, sexual orientation and gender identity in the Commonwealth: from history and law to developing activism and transnational dialogues 1 Corinne Lennox and Matthew Waites 2 -

FOI Letter Template

Royal, Ceremonial & Honours Unit Protocol Directorate Foreign and Commonwealth Office King Charles Street London SW1A 2AH Website: https://www.gov.uk 22 February 2016 Dear FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT 2000 REQUEST REF: 0082-16 Thank you for your email of 23 January asking for information under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) 2000. You asked: “I would be pleased to receive information and correspondence held by the FCO between and within the offices of FCO ministers, FCO protocol and Royal matters unit department concerning the rules and regulations pertaining to the use of titles of honour, such as knighthoods, granted by The Queen or her official representatives in right of another Commonwealth Realm, to UK and dual nationals of the Queen’s Commonwealth realms, any correspondence on the changing of such rules and regulations for UK nationals and dual UK nationals who are also a national of another Commonwealth Realm.” We can confirm that the Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO) does hold information relevant to your request. Some of the information that we hold which is relevant to your request is, in our view, already reasonably accessible to you. Under section 21 of the Act, we are not required to provide information in response to a request if it is already reasonably accessible to the applicant. Responses to Parliamentary Questions on this subject are available to view at www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written- questions-answers using the keyword “knighthoods”. However, other information and correspondence on the use of titles of honours has been withheld as it is exempt under section 37(1)(a) of the Freedom of Information Act (FOI) – communications with, or on behalf of, the Sovereign. -

What Goes up Must Come Down: Integrating Air and Water Quality Monitoring for Nutrients Helen M Amos, Chelcy Miniat, Jason A

Subscriber access provided by NASA GODDARD SPACE FLIGHT CTR Feature What Goes Up Must Come Down: Integrating Air and Water Quality Monitoring for Nutrients Helen M Amos, Chelcy Miniat, Jason A. Lynch, Jana E. Compton, Pamela Templer, Lori Sprague, Denice Marie Shaw, Douglas A. Burns, Anne W. Rea, David R Whitall, Myles Latoya, David Gay, Mark Nilles, John T. Walker, Anita Rose, Jerad Bales, Jeffery Deacon, and Richard Pouyat Environ. Sci. Technol., Just Accepted Manuscript • DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.8b03504 • Publication Date (Web): 19 Sep 2018 Downloaded from http://pubs.acs.org on September 21, 2018 Just Accepted “Just Accepted” manuscripts have been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication. They are posted online prior to technical editing, formatting for publication and author proofing. The American Chemical Society provides “Just Accepted” as a service to the research community to expedite the dissemination of scientific material as soon as possible after acceptance. “Just Accepted” manuscripts appear in full in PDF format accompanied by an HTML abstract. “Just Accepted” manuscripts have been fully peer reviewed, but should not be considered the official version of record. They are citable by the Digital Object Identifier (DOI®). “Just Accepted” is an optional service offered to authors. Therefore, the “Just Accepted” Web site may not include all articles that will be published in the journal. After a manuscript is technically edited and formatted, it will be removed from the “Just Accepted” Web site and published as an ASAP article. Note that technical editing may introduce minor changes to the manuscript text and/or graphics which could affect content, and all legal disclaimers and ethical guidelines that apply to the journal pertain. -

Swanbourne History Trail

Swanbourne History Trail BACKGROUND TO THE VILLAGE The village of Swanbourne can trace its roots back to Anglo- Saxon times. The first mention of ‘Suanaburna’ comes in a document of 792 relating to the granting by King Offa of the parishes of Winslow, Granborough and Little Horwood for the establishment of St. Alban’s Abbey. The name probably means ‘peasant’s brook’, and so originally referred to the stream which flows along the western border of the parish, rather than the village itself. At the time of the Doomsday Book in 1086, the parish was divided between 5 landholders, although one of these was extremely small. One of the major landholders was King William (The Bastard or Conqueror) who took over land belonging to King Harold. William’s half-brother the Count of Mortain also held land, and the other two major landholders were Walter Giffard and William, son of Ansculf. In 1206, much of the village lands were granted to Woburn Abbey, but following Henry VIII’s dissolution of the Abbey in 1538, the land and Overlordship of the Manor of Swanbourne was sold on to the Fortescues, then the Adams, then the Deverells and finally the Fremantles. This trail starts from The Betsey Wynne public house which was opened in July 2006. The pub takes its name from Betsey Fremantle (nee Wynne), wife of Thomas Fremantle, who was a captain in the Royal Navy and a close friend of Admiral Nelson. Thomas and Betsey, together with their new-born son, also called Thomas, moved to Swanbourne in 1798. -

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

The Case of Canadian and Indian Bilateral Trade

Études canadiennes / Canadian Studies Revue interdisciplinaire des études canadiennes en France 75 | 2013 Canada and the Commonwealth Enhancing Trade Relations between Commonwealth Members: the Case of Canadian and Indian bilateral trade Claire Heuillard Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/eccs/273 DOI: 10.4000/eccs.273 ISSN: 2429-4667 Publisher Association française des études canadiennes (AFEC) Printed version Date of publication: 1 December 2013 Number of pages: 81-95 ISSN: 0153-1700 Electronic reference Claire Heuillard, « Enhancing Trade Relations between Commonwealth Members: the Case of Canadian and Indian bilateral trade », Études canadiennes / Canadian Studies [Online], 75 | 2013, Online since 01 December 2015, connection on 02 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/eccs/273 ; DOI : 10.4000/eccs.273 AFEC ENHANCING TRADE RELATIONS BETWEEN COMMONWEALTH MEMBERS: THE CASE OF CANADIAN AND INDIAN BILATERAL TRADE Claire HEUILLARD Université de Paris 2, Panthéon-Assas Cet article étudie le faible niveau du commerce bilatéral entre le Canada et l’Inde au cours de la seconde moitié du XXème siècle, et analyse la dynamique des relations actuelles. Tandis que le choix de non-alignement de la part de l’Inde engendra des tensions géopolitiques complexes à l’origine de barrières entre ces deux pays durant la Guerre Froide, l’intensification de la mondialisation au XXIème siècle les a conduits à envisager de nouveaux partenariats stratégiques. Cet article met l’accent sur la nécessité d’améliorer la compréhension mutuelle, afin d’éviter de compromettre les efforts considérables qui ont été faits ces dix dernières années pour développer le commerce bilatéral. This article examines the surprisingly low levels of bilateral trade between Canada and India throughout the late 20th century and explores the dynamics of present-day relations. -

Suki and Tobacco Use Among the Itaukei People of Fiji

Suki and tobacco use among the iTaukei people of Fiji 2019 Suki and tobacco use among the iTaukei people of Fiji Citation: Correspondence to: Centre of Research Excellence: Professor Marewa Glover Indigenous Sovereignty and Smoking. Centre of Research Excellence: (2019). Suki and tobacco use among Indigenous Sovereignty & Smoking the iTaukei people of Fiji. New Zealand: Centre of Research Excellence: P.O. Box 89186 Indigenous Sovereignty Torbay, Auckland 0742 & Smoking. New Zealand ISBN: 978-0-473-48538-2 Email: [email protected] ISBN: 978-0-473-48539-9 (online) www.coreiss.com Contents Ngā mihi / Acknowledgements 7 Introduction 9 About Fiji 13 iTaukei Health 17 Suki and Tobacco in Fiji 23 Kava 35 What has been done to stop smoking? 39 Conclusion 43 Endnotes 47 Appendix A: Research Method 53 Ngā mihi / Acknowledgements We would like to thank the many people who shared their time and knowledge with us. We especially want to thank Ms Ana Maria Naimasi and Mr Alusio Setariki. Mr Setariki is an expert in his own right about the history of tobacco use in Fiji and the introduction of suki from India. This report is partly his story. Thanks also to Mr Shivnay Naidu, Head Researcher of the National Research Unit at the Fiji Ministry of Health for insights into the state of the statistics on smoking in Fiji. In New Zealand, we are grateful to Andrew Chappell at the Institute of Environmental Science and Research (ESR) for conducting tests on the samples of tobacco we gathered from Fiji and India. We also want to thank the experts that joined our India study group – Atakan Befrits and Samrat Chowdery, and locals who helped guide and translate for us – Bala Gopalan of the Foundation for a Smoke-Free World, Rapper AJ RWB and our Banyan Tour Guides Vasanth Rajan and Rari from Chennai. -

The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century

“No Mere Child’s Play”: The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century by Kevin Woodger A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Kevin Woodger 2020 “No Mere Child’s Play”: The Canadian Cadet Movement and the Boy Scouts of Canada in the Twentieth Century Kevin Woodger Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto Abstract This dissertation examines the Canadian Cadet Movement and Boy Scouts Association of Canada, seeking to put Canada’s two largest uniformed youth movements for boys into sustained conversation. It does this in order to analyse the ways in which both movements sought to form masculine national and imperial subjects from their adolescent members. Between the end of the First World War and the late 1960s, the Cadets and Scouts shared a number of ideals that formed the basis of their similar, yet distinct, youth training programs. These ideals included loyalty and service, including military service, to the nation and Empire. The men that scouts and cadets were to grow up to become, as far as their adult leaders envisioned, would be disciplined and law-abiding citizens and workers, who would willingly and happily accept their place in Canadian society. However, these adult-led movements were not always successful in their shared mission of turning boys into their ideal-type of men. The active participation and complicity of their teenaged members, as peer leaders, disciplinary subjects, and as recipients of youth training, was central to their success. -

VAN DIEMEN's LAND COMPANY Records, 1824-1930 Reels M337

AUSTRALIAN JOINT COPYING PROJECT VAN DIEMEN’S LAND COMPANY Records, 1824-1930 Reels M337-64, M585-89 Van Diemen’s Land Company 35 Copthall Avenue London EC2 National Library of Australia State Library of New South Wales Filmed: 1960-61, 1964 CONTENTS Page 3 Historical note M337-64 4 Minutes of Court of Directors, 1824-1904 4 Outward letter books, 1825-1902 6 Inward letters and despatches, 1833-99 9 Letter books (Van Diemen’s Land), 1826-48 11 Miscellaneous papers, 1825-1915 14 Maps, plan and drawings, 1827-32 14 Annual reports, 1854-1922 M585-89 15 Legal documents, 1825-77 15 Accounts, 1833-55 16 Tasmanian letter books, 1848-59 17 Conveyances, 1851-1930 18 Miscellaneous papers 18 Index to despatches 2 HISTORICAL NOTE In 1824 a group of woollen mill owners, wool merchants, bankers and investors met in London to consider establishing a land company in Van Diemen’s Land similar to the Australian Agricultural Company in New South Wales. Encouraged by the support of William Sorell, the former Lieutenant- Governor, and Edward Curr, who had recently returned from the colony, they formed the Van Diemen’s Land Company and applied to Lord Bathurst for a grant of 500,000 acres. Bathurst agreed to a grant of 250,000 acres. The Van Diemen’s Land Company received a royal charter in 1825 giving it the right to cultivate land, build roads and bridges, lend money to colonists, execute public works, and build and buy houses, wharves and other buildings. Curr was appointed the chief agent of the Company in Van Diemen’s Land. -

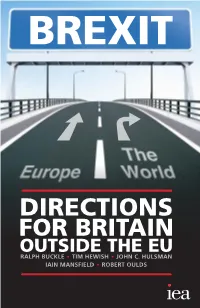

Directions for Britain Outside the Eu Ralph Buckle • Tim Hewish • John C

BREXIT DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE • TIM HEWISH • JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD • ROBERT OULDS BREXIT: Directions for Britain Outside the EU BREXIT: DIRECTIONS FOR BRITAIN OUTSIDE THE EU RALPH BUCKLE TIM HEWISH JOHN C. HULSMAN IAIN MANSFIELD ROBERT OULDS First published in Great Britain in 2015 by The Institute of Economic Affairs 2 Lord North Street Westminster London SW1P 3LB in association with London Publishing Partnership Ltd www.londonpublishingpartnership.co.uk The mission of the Institute of Economic Affairs is to improve understanding of the fundamental institutions of a free society by analysing and expounding the role of markets in solving economic and social problems. Copyright © The Institute of Economic Affairs 2015 The moral right of the author has been asserted. All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photo- copying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN 978-0-255-36682-3 (interactive PDF) Many IEA publications are translated into languages other than English or are reprinted. Permission to translate or to reprint should be sought from the Director General at the address above. Typeset in Kepler by T&T Productions Ltd www.tandtproductions.com -

Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms

Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms Case Studies and Frameworks Key Principles of Public Sector Reforms Case Studies and Frameworks Advance proof copy. The final edition will be available in December 2016. © Commonwealth Secretariat 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or otherwise without the permission of the publisher. Views and opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the author and should in no way be attributed to the institutions to which they are affiliated or to the Commonwealth Secretariat. Wherever possible, the Commonwealth Secretariat uses paper sourced from responsible forests or from sources that minimise a destructive impact on the environment. Printed and published by the Commonwealth Secretariat. Table of contents Table of contents ........................................................................................ 1 Acknowledgements ...................................................................................... 3 Foreword .................................................................................................. 5 The Key Principles of Public Sector Reform ......................................................... 8 Principle 1. A new pragmatic and results–oriented framework ................................. 12 Case Study 1.1 South Africa. Measuring organisational productivity in the public service: North