The Origin and Growth of the Anglican Church in Newfoundland And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

Memorial to Vladimir Stephen Papezik 1927-1984 GORDON A

Memorial to Vladimir Stephen Papezik 1927-1984 GORDON A. GROSS Geological Survey o f Canada, Ottawa, Canada K1A 0E8 V. Stephen Papezik, Professor of Geology at Memorial University in Newfoundland, was an inspiring teacher, a congenial professional colleague, and a devoted scien tist. His death on June 23, 1984. after a year of illness, caused a serious loss to the geologic and mineralogic fraternities and to his many friends throughout Canada and the world. Stephen lived through a period of uncertainty and turmoil, but he was decisive and un compromising in maintaining the high principles and standards that characterized all aspects of his life. He was born in Brno, Czechoslovakia, on Febru ary 5, 1927, and entered the University of Masaryk in Brno in 1946, to study geography and history. His interest in geology was aroused in his second year, and he changed his emphasis to geology and physical geog raphy. In one of his personal papers he notes, “After the Communist seizure of power in Czechoslovakia, at the beginning of my third year at the University, I decided that the new government and I were mutually incompatible, and I escaped to Austria, then under Four Power occupation.” The story of his escape to freedom is sensational reading; one incident in it illustrates a major attribute of his character. Because of currency reforms in Austria, he made a secret return trip to an Austrian town which was under Communist occupation at the time to see that a priest who had assisted him was properly repaid. After escaping Czechoslovakia, Stephen was determined to reestablish himself in a scientific career. -

Building Canadian National Identity Within the State and Through Ice Hockey: a Political Analysis of the Donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 12-9-2015 12:00 AM Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 Jordan Goldstein The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Robert K. Barney The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Jordan Goldstein 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Intellectual History Commons, Political History Commons, Political Theory Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Recommended Citation Goldstein, Jordan, "Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3416. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3416 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Stanley’s Political Scaffold Building Canadian National Identity within the State and through Ice Hockey: A political analysis of the donation of the Stanley Cup, 1888-1893 By Jordan Goldstein Graduate Program in Kinesiology A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Jordan Goldstein 2015 ii Abstract The Stanley Cup elicits strong emotions related to Canadian national identity despite its association as a professional ice hockey trophy. -

Download (6MB)

Library and Bibliotheque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de !'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33450-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-33450-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a Ia Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I' Internet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve Ia propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits meraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni Ia these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. reproduced without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a Ia loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur Ia protection de Ia vie privee, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this thesis. -

Total of 10 Pages Only May Be Xeroxed

CENTRE FOR NeWFOUNDLAND STlll>lfS TOTAL OF 10 PAGES ONLY MAY BE XEROXED Evangelicalism in the Anglican Church in Nineteenth-Century Newfoundland by Heather Rose Russell A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department ofReligious Studies Memorial University ofNewfoundland November, 2005 St. John's Newfoundland Library and Bibliotheque et 1+1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de !'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-19393-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-19393-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a Ia Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par !'Internet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve Ia propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni Ia these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. -

American Eel Anguilla Rostrata

COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the American Eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada SPECIAL CONCERN 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 71 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge V. Tremblay, D.K. Cairns, F. Caron, J.M. Casselman, and N.E. Mandrak for writing the status report on the American eel Anguilla rostrata in Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair (Freshwater Fishes) COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. Funding for this report was provided by Environment Canada. For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur l’anguille d'Amérique (Anguilla rostrata) au Canada. Cover illustration: American eel — (Lesueur 1817). From Scott and Crossman (1973) by permission. ©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada 2004 Catalogue No. CW69-14/458-2006E-PDF ISBN 0-662-43225-8 Recycled paper COSEWIC Assessment Summary Assessment Summary – April 2006 Common name American eel Scientific name Anguilla rostrata Status Special Concern Reason for designation Indicators of the status of the total Canadian component of this species are not available. -

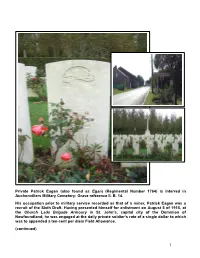

Private Patrick Eagan (Also Found As Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) Is Interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave Reference II

Private Patrick Eagan (also found as Egan) (Regimental Number 1764) is interred in Auchonvillers Military Cemetery: Grave reference II. B. 14. His occupation prior to military service recorded as that of a miner, Patrick Eagan was a recruit of the Sixth Draft. Having presented himself for enlistment on August 5 of 1915, at the Church Lads Brigade Armoury in St. John’s, capital city of the Dominion of Newfoundland, he was engaged at the daily private soldier’s rate of a single dollar to which was to appended a ten-cent per diem Field Allowance. (continued) 1 Just one day after having enlisted, on August 6 he was to return to the CLB Armoury on Harvey Road. On this second occasion Patrick Eagan was to undergo a medical examination, a procedure which was to pronounce him as being…Fit for Foreign Service. And it must have been only hours afterwards again that there then came the final formality of his enlistment: attestation. On the same August 6 he pledged his allegiance to the reigning monarch, George V, at which moment Patrick Eagan thus became…a soldier of the King. A further, and lengthier, waiting-period was now in store for the recruits of this draft, designated as ‘G’ Company, before they were to depart from Newfoundland for…overseas service. Private Eagan, Regimental Number 1764, was not to be again called upon until October 27, after a period of twelve weeks less two days. Where he was to spend this intervening time appears not to have been recorded although he possibly returned temporarily to his work and perhaps would have been able to spend time with family and friends in the Bonavista Bay community of Keels – but, of course, this is only speculation. -

American Eel (Anguilla Rostrata )

American Eel (Anguilla rostrata ) Abstract The American eel ( Anguilla rostrata ) is a freshwater eel native in North America. Its smooth, elongated, “snake-like” body is one of the most noted characteristics of this species and the other species in this family. The American Eel is a catadromous fish, exhibiting behavior opposite that of the anadromous river herring and Atlantic salmon. This means that they live primarily in freshwater, but migrate to marine waters to reproduce. Eels are born in the Sargasso Sea and then as larvae and young eels travel upstream into freshwater. When they are fully mature and ready to reproduce, they travel back downstream into the Sargasso Sea,which is located in the Caribbean, east of the Bahamas and north of the West Indies, where they were born (Massie 1998). This species is most common along the Atlantic Coast in North America but its range can sometimes even extend as far as the northern shores of South America (Fahay 1978). Context & Content The American Eel belongs in the order of Anguilliformes and the family Anguillidae, which consist of freshwater eels. The scientific name of this particular species is Anguilla rostrata; “Anguilla” meaning the eel and “rostrata” derived from the word rostratus meaning long-nosed (Ross 2001). General Characteristics The American Eel goes by many common names; some names that are more well-known include: Atlantic eel, black eel, Boston eel, bronze eel, common eel, freshwater eel, glass eel, green eel, little eel, river eel, silver eel, slippery eel, snakefish and yellow eel. Many of these names are derived from the various colorations they have during their lifetime. -

The Seventeenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland

Northeast Historical Archaeology Volume 41 Article 2 2012 The eveS nteenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland Arthur R. Clausnitzer Jr. Barry C. Gaulton Follow this and additional works at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha Part of the Archaeological Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Clausnitzer, Arthur R. Jr. and Gaulton, Barry C. (2012) "The eS venteenth Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland," Northeast Historical Archaeology: Vol. 41 41, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.22191/neha/vol41/iss1/2 Available at: http://orb.binghamton.edu/neha/vol41/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). It has been accepted for inclusion in Northeast Historical Archaeology by an authorized editor of The Open Repository @ Binghamton (The ORB). For more information, please contact [email protected]. Northeast Historical Archaeology/Vol. 41, 2012 1 The Seventeenth-Century Brewhouse and Bakery at Ferryland, Newfoundland Arthur R. Clausnitzer, Jr. and Barry C. Gaulton In 2001 archaeologists working at the 17th-century English settlement at Ferryland, Newfoundland, uncovered evidence of an early structure beneath a mid-to-late century gentry dwelling. A preliminary analysis of the architectural features and material culture from related deposits tentatively identified the structure as a brewhouse and bakery, likely the same “brewhouse room” mentioned in a 1622 letter from the colony. Further analysis of this material in 2010 confirmed the identification and dating of this structure. Comparison of the Ferryland brewhouse to data from both documentary and archaeological sources revealed some unusual features. When analyzed within the context of the original Calvert period settlement, these features provide additional evidence for the interpretation of the initial settlement at Ferryland not as a corporate colony such as Jamestown or Cupids, but as a small country manor home for George Calvert and his family. -

Auozyme Variation in Picea Mariana from Newfoundland: Discussion

1471 DISCUSSIONS AUozyme variation In Picea mariana from Newfoundland1: Discussion William B. Critchfield Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, P.O. Box 245, Berkeley, CA, U.S.A. 94701 Received April 21,1987 Accepted June 26, 1987 In their recent paper describing the distribution of genetic grew on both north and south coasts near the end of the variation in black spruce (Picea mariana (Mill.) B.S.P.) on the Pleistocene and beginning of the Holocene. At the southern site, island of Newfoundland, Yeh et el. (1986) concluded that a near the tip of the Burin Peninsula, Anderson (1983) found an center of variability in west-central Newfoundland derived from annual deposition rate of up to 30 spruce pollen grains/cm2 ancestral populations that persisted on the island during the last through the late Wisconsin, and he attributed this low level to (Wisconsin) glaciation. They attributed to Munns (1938) the long-distance transport from New England. At the northern site, "theory that part or all of such an area was ice-free during the on Notre Dame Bay, maximum influx of spruce p6Uen was Wisconsin glaciation/* Munns's publication consists of tree about the same as at the Burin site (Macpherson and Anderson distribution maps, long since superseded and not very accurate 198S). Spruce pollen was not identified to species in these even when they were published; map 29, for example, wrongly deposits, but at two sites on the Avalon Peninsula, in southeast shows black spruce widely distributed in West Virginia, ern Newfoundland, pollen was identified as black spruce. -

Ward Their Work As a Consequence of This Wider Conception of Social Service

676 LEGISLATION AND PRINCIPAL EVENTS ward their work as a consequence of this wider conception of social service. Charity has been so organized as to aim at the prevention rather" than the mere palliation of destitution. Hospital authorities, too, have been convinced that prevention is better than cure, and have organized out-patient departments for the dissemination of medical information and assistance among the poorer classes. The great prob lems of feeble-mindedness and venereal disease have also been courageously attacked, and considerable progress has been made in arousing the public mind and conscience to the greatness of the dangers resulting from these scourges of humanity. All these activities above described have led to an active demand for the services of trained social workers. The universities were called upon to supply such workers, and in 1914 the University of Toronto opened its Department of Social Service, the first institution in Canada to pro vide regular academic training for social workers. The success of this venture led to the establishment of similar departments in other Canadian universities, notably McGill and the University of Montreal, while Queen's, Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba Universities have offered part time courses or special lectures on topics of social service. To co-ordinate the social activities of the agencies above de scribed, the Social Service Council of Canada was established in 1907. It consists of a federal union of eighteen Dominion-wide bodies and nine provincial Social Service -

This Guide Was Prepared and Written by Roberta Thomas, Contract Archivist, During the Summer of 2000

1 This guide was prepared and written by Roberta Thomas, contract archivist, during the summer of 2000. Financial assistance was provided by the Canadian Council of Archives, through the Association of Newfoundland and Labrador Archives. This guide was updated by Pamela Hayter, October 6, 2010. This guide was updated by Daphne Clarke, February 8, 2018. Clarence Dewling, Archivist TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 List of Holdings ........................................................ 3 Business Records ...................................................... 7 Church and Parish Records .................................... 22 Education and Schools…………………………..52 Courts and Administration of Justice ..................... 65 Societies and Organizations ................................... 73 Personal Papers ..................................................... 102 Manuscripts .......................................................... 136 Index……………………………………………2 LIST OF THE HOLDINGS OF THE TRINITY 3 HISTORICAL SOCIETY ARCHIVES BUSINESS RECORDS Slade fonds, 1807-1861. - 84 cm textual records. E. Batson fonds, 1914 – 1974 – 156.40 cm textual records Grieve and Bremner fonds, 1863-1902 (predominant), 1832-1902 (inclusive). - 7.5 m textual records Hiscock Family Fonds, 1947 – 1963 – 12 cm textual records Ryan Brothers, Trinity, fonds, 1892 - 1948. – 6.19 m textual records Robinson Brooking & Co. Price Book, 1850-1858. - 0.5 cm textual records CHURCH AND PARISH RECORDS The Anglican Parish of Trinity fonds - 1753 -2017 – 87.75 cm textual records St. Paul=s Anglican Church (Trinity) fonds. - 1756 - 2010 – 136.5 cm textual records St. Paul’s Guild (Trinity) ACW fonds – 1900 – 1984 – 20.5 cm textual records Church of the Holy Nativity (Little Harbour) fonds, 1931-1964. - 4 cm textual records St. Augustine=s Church (British Harbour) fonds, 1854 - 1968. - 9 cm textual records St. Nicholas Church (Ivanhoe) fonds, 1926-1964. - 4 cm textual records St. George=s Church (Ireland=s Eye) fonds, 1888-1965.