Literature in Translation Sampler

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armenophobia in Azerbaijan

Հարգելի՛ ընթերցող, Արցախի Երիտասարդ Գիտնականների և Մասնագետների Միավորման (ԱԵԳՄՄ) նախագիծ հանդիսացող Արցախի Էլեկտրոնային Գրադարանի կայքում տեղադրվում են Արցախի վերաբերյալ գիտավերլուծական, ճանաչողական և գեղարվեստական նյութեր` հայերեն, ռուսերեն և անգլերեն լեզուներով: Նյութերը կարող եք ներբեռնել ԱՆՎՃԱՐ: Էլեկտրոնային գրադարանի նյութերն այլ կայքերում տեղադրելու համար պետք է ստանալ ԱԵԳՄՄ-ի թույլտվությունը և նշել անհրաժեշտ տվյալները: Շնորհակալություն ենք հայտնում բոլոր հեղինակներին և հրատարակիչներին` աշխատանքների էլեկտրոնային տարբերակները կայքում տեղադրելու թույլտվության համար: Уважаемый читатель! На сайте Электронной библиотеки Арцаха, являющейся проектом Объединения Молодых Учёных и Специалистов Арцаха (ОМУСA), размещаются научно-аналитические, познавательные и художественные материалы об Арцахе на армянском, русском и английском языках. Материалы можете скачать БЕСПЛАТНО. Для того, чтобы размещать любой материал Электронной библиотеки на другом сайте, вы должны сначала получить разрешение ОМУСА и указать необходимые данные. Мы благодарим всех авторов и издателей за разрешение размещать электронные версии своих работ на этом сайте. Dear reader, The Union of Young Scientists and Specialists of Artsakh (UYSSA) presents its project - Artsakh E-Library website, where you can find and download for FREE scientific and research, cognitive and literary materials on Artsakh in Armenian, Russian and English languages. If re-using any material from our site you have first to get the UYSSA approval and specify the required data. We thank all the authors -

Russian Restaurant & Vodka Lounge

Moscow on the hill Russian Restaurant & Vodka Lounge LATE NIGHT MENU Served Friday and Saturday 10pm -12am Appetizers Borscht Soup of the Day Bowl 5.95/Cup 3.95 Bowl 5.95/Cup 3.95 Classic Russian beet, cabbage and potato soup Ask your server for tonight‘s selection garnished with sour cream and fresh dill Pirozhki (Beef or Cabbage) 7.95 Blini with Chicken 7.95 Two filled pastries, served with Two crepes stuffed with braised chicken, dill-sour cream sauce served with sour cream Cheboureki 7.95 Moscow Fries 6.95 Ground lamb stuffed pastries puffed in hot oil, Basket of fried dill potatoes with served with tomato-garlic relish dipping sauces ZAKUSKI PLATE 8.95 DUCK FAT POTATOES 6.95 Local Russian charcuterie and cheeses Fingerling Potatoes, Mushrooms, Caramelized Onions, served with mustard, chutney and toasts Fresh Herbs, Garlic Crème ROASTED BEET SALAD 7.95 SCHNITZEL SANDWICH 12.95 Beets, greens, Candied Pecans, Goat Cheese, Crisp fried pork loin, Adjika Aoili, Lettuce, Tomato, Pomegranate vinaigrette Pickled Cabbage Wild Rice Cabbage Rolls 16.95 Beef Stroganoff 23.95 Pork, beef & wild rice filled cabbage leaves braised in Beef filet strips in black pepper sour cream sauce with vegetable sauce, garnished mushrooms & onion, parsley mashed potatoes, with sour cream and fresh dill vegetables of the day Hand-Made Dumplings Large $17.95 / Small $11.95 Siberian Pelmeni Dumplings Vareniki Dumplings (Vegetarian) Beef & pork filled dumplings brushed with butter, Ukrainian dumplings filled with potato & caramelized garnished with sour cream, served with vinegar onion, garnished with sour cream & fresh dill Peasant Pelmeni Beef & pork filled dumplings simmered and broiled with mushroom sauce & cheese PELMENI OR VARENIKI ST PAUL 9.95 Fried crisp with Bulgarian feta and a sweet and sour beet gastrique ON W TH E O C H S I L O L 371 Selby Ave. -

Alyonka Russian Cuisine Menu

ZAKOOSKI/COLD APPETIZERS Served with your choice of toasted fresh bread or pita bread “Shuba” Layered salad with smoked salmon, shredded potatoes, carrots, beets and with a touch of mayo $12.00 Marinated carrot or Mushroom salad Marinated with a touch of white vinegar and Russian sunflower oil and spices $6.00 Smoked Gouda spread with crackers and pita bread $9.00 Garden Salad Organic spring mix, romaine lettuce, cherry tomatoes, cucumbers, green scallions, parsley, cranberries, pine nuts dressed in olive oil, and balsamic vinegar reduction $10.00. GORIYACHIE ZAKOOSKI/HOT APPETIZERS Chebureki Deep-fried turnover with your choice of meat or vegetable filling $5.00 Blini Russian crepes Four plain with sour cream, salmon caviar and smoked salmon $12.00 Ground beef and mushrooms $9.00 Vegetable filling: onion, carrots, butternut squash, celery, cabbage, parsley $9.00 Baked Pirozhki $4.00 Meat filling (mix of beef, chicken, and rice) Cabbage filling Dry fruit chutney Vegetarian Borscht Traditional Russian soup made of beets and garden vegetables served with sour cream and garlic toast Cup $6.00 Bowl $9.00 Order on-line for pickup or delivery 2870 W State St. | Boise | ID 208.344.8996 | alyonkarussiancuisine.com ENTREES ask your server for daily specials Beef Stroganoff with choice of seasoned rice, egg noodles, or buckwheat $19.95 Pork Shish Kebab with sauce, seasoned rice and marinated carrot salad $16.95 Stuffed Sweet Pepper filled with seasoned rice and ground beef $16.95 Pelmeni Russian style dumplings with meat filling served with sour cream $14.95 -

Favorite Foods of the World.Xlsx

FAVORITE FOODS OF THE WORLD - VOTING BRACKETS First Round Second Round Third Round Fourth Round Sweet Sixteen Elite Eight Final Four Championship Final Four Elite Eight Sweet Sixteen Fourth Round Third Round Second Round First Round Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Votes Blintzes Duck Confit Papadums Laksa Jambalaya Burrito Cornish Pasty Bulgogi Nori Torta Vegemite Toast Crepes Tagliatelle al Ragù Bouneschlupp Potato Pancakes Hummus Gazpacho Lumpia Philly Cheesesteak Cannelloni Tiramisu Kugel Arepas Cullen Skink Börek Hot and Sour Soup Gelato Bibimbap Black Forest Cake Mousse Croissants Soba Bockwurst Churros Parathas Cream Stew Brie de Meaux Hutspot Crab Rangoon Cupcakes Kartoffelsalat Feta Cheese Kroppkaka PBJ Sandwich Gnocchi Saganaki Mochi Pretzels Chicken Fried Steak Champ Chutney Kofta Pizza Napoletana Étouffée Satay Kebabs Pelmeni Tandoori Chicken Macaroons Yakitori Cheeseburger Penne Pinakbet Dim Sum DIVISION ONE DIVISION TWO Lefse Pad Thai Fastnachts Empanadas Lamb Vindaloo Panzanella Kombu Tourtiere Brownies Falafel Udon Chiles Rellenos Manicotti Borscht Masala Dosa Banh Mi Som Tam BLT Sanwich New England Clam Chowder Smoked Eel Sauerbraten Shumai Moqueca Bubble & Squeak Wontons Cracked Conch Spanakopita Rendang Churrasco Nachos Egg Rolls Knish Pastel de Nata Linzer Torte Chicken Cordon Bleu Chapati Poke Chili con Carne Jollof Rice Ratatouille Hushpuppies Goulash Pernil Weisswurst Gyros Chilli Crab Tonkatsu Speculaas Cookies Fish & Chips Fajitas Gravlax Mozzarella Cheese -

Russian National Cuisine: a View from Outside

International Journal of Innovation and Research in Educational Sciences Volume 6, Issue 2, ISSN (Online) : 2349–5219 Russian National Cuisine: A View from Outside Natalya V. Kravchenko Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia. Date of publication (dd/mm/yyyy): 14/03/2019 Abstract – The article tackles the issue of how Russian national cuisine is perceived by foreigners. It compares Russians’ beliefs about their own national cuisine with foreigners’ observations about it and some encyclopedic facts about a number of “traditional” Russian dishes. As a research method, the cross-cultural comparison is used. As a result, it proves that some Russian dishes are not so Russian in origin and states that foreigners often find the taste of these dishes unusual. So, it may be challenging for representatives of one culture to adjust to another national cuisine. Keywords – Cultural Anthropology, Foreigners’ Travel-Notes and Observations, National Cuisines and Russian National Cuisine. I. INTRODUCTION Nowadays we live in a global world or so called “global village” connected with each other by different means of transport and communication. It’s becoming incredibly easy to explore other nations and cultures either by travelling or by using social media. It has resulted in such branches of humanities as cross-cultural studies and cultural anthropology being on peak of their demand. Here I would like to pay special attention to cultural anthropology. As a branch of academia it tackles the issue of a person’s cultural development including all knowledge from Humanities. (1) In this paper I will stick to a relatively new field of cultural anthropology called history of everyday life culture. -

![Cahiers Du Monde Russe, 43/4 | 2002, « Intellectuels Et Intelligentsia » [Online], Online Since 18 January 2007, Connection on 06 October 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0633/cahiers-du-monde-russe-43-4-2002-%C2%AB-intellectuels-et-intelligentsia-%C2%BB-online-online-since-18-january-2007-connection-on-06-october-2020-1110633.webp)

Cahiers Du Monde Russe, 43/4 | 2002, « Intellectuels Et Intelligentsia » [Online], Online Since 18 January 2007, Connection on 06 October 2020

Cahiers du monde russe Russie - Empire russe - Union soviétique et États indépendants 43/4 | 2002 Intellectuels et intelligentsia Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/1194 DOI: 10.4000/monderusse.1194 ISSN: 1777-5388 Publisher Éditions de l’EHESS Printed version Date of publication: 30 December 2002 ISBN: 2-7132-1796-2 ISSN: 1252-6576 Electronic reference Cahiers du monde russe, 43/4 | 2002, « Intellectuels et intelligentsia » [Online], Online since 18 January 2007, connection on 06 October 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/monderusse/1194 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/monderusse.1194 This text was automatically generated on 6 October 2020. © École des hautes études en sciences sociales, Paris. 1 Les articles que nous publions ici ont été choisis parmi les contributions d’un colloque franco-russe qui s’est tenu en 2000 à Moscou, à l’Institut d’histoire universelle de l’Académie des sciences de Russie et qui fut organisé avec la participation de l’École des hautes études en sciences sociales et la Maison des sciences de l’homme de Paris. Bien que l’ensemble des actes du colloque ait fait l’objet d’une publication en russe (Intelligencija v istorii. Obrazovannyj chelovek v predstavlenijah i social´noj dejstvitel´nosti = Les intellectuels dans l’histoire moderne et contemporaine. Représentations et réalités sociales, Moscou, RAN, Institut vseobshchej istorii, 2001), nous avons jugé utile de faire connaître au public français les études qui nous ont paru les plus représentatives dans le contexte international du débat sur l’intelligentsia russe. Cahiers du monde russe, 43/4 | 2002 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Intellectuels et intelligentsia Comparer l’incomparable Le général et le particulier dans l’idée d’« homme instruit » Denis A. -

Flavors of Eastern Europe & Russia

Name Date Class Section 5 Eastern Europe & Russia Flavors of Eastern Europe & Russia Directions: Read this article and then answer the "Reading Check" questions that follow. Complete the "Appli cation Activities" as directed by your teacher. It's time to stretch your imagination. If you've never been to the area of the world in this section, it may be difficult to imagine its vastness. If you were to travel all the way across Russia, for example, you would pass through eleven time zones. This part of the world includes countries with names that aren't easy to pronounce—or spell. Some may be more familiar to you than others. With the world continually "growing smaller," however, you'll find that far away places are gradually becoming more familiar. To begin your look at this part of the world, move east from Western Europe. There you'll find the coun tries of Eastern Europe. Even farther east lie Russia and the independent republics. While many of these coun tries share certain foodways, they also have distinctions that set cuisines apart. sus nations of Armenia, Azerbaijan (a-zuhr-by- Identifying the Countries JAHN), and Georgia are also among the repub The area of the world covered in this section lics. These three countries share the Caucasus includes the single largest country in the world. Mountains. It also contains some of the most recently created countries. Food Similarities • Eastern Europe. The Eastern European coun tries include Estonia, Latvia (LAT-vee-uh), and Countries in Eastern Europe, Russia, and the Lithuania (li-thuh-WAY-nee-uh), which are independent republics season many of their dishes often called the Baltic States because they're on with many similar ingredients: onions, mushrooms, the Baltic Sea. -

Azerbaijan0913 Forupload 1.Pdf

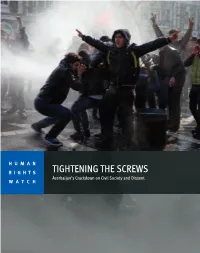

HUMAN RIGHTS TIGHTENING THE SCREWS Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent WATCH Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Copyright © 2013 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN: 978-1-62313-0473 Cover design by Rafael Jimenez Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. Human Rights Watch is an international organization with staff in more than 40 countries, and offices in Amsterdam, Beirut, Berlin, Brussels, Chicago, Geneva, Goma, Johannesburg, London, Los Angeles, Moscow, Nairobi, New York, Paris, San Francisco, Tokyo, Toronto, Tunis, Washington DC, and Zurich. For more information, please visit our website: http://www.hrw.org SEPTEMBER 2013 978-1-62313-0473 Tightening the Screws Azerbaijan’s Crackdown on Civil Society and Dissent Summary ........................................................................................................................... 1 Arrest and Imprisonment ......................................................................................................... -

Echo of Khojaly Tragedy

CHAPTER 3 ECHO OF KHOJALY Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y ─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────── CONTENTS Kommersant (Moscow) (February 27, 2002) ..................................................................................... 15 15 th year of Khojaly genocide commemorated (February 26, 2007) ................................................ 16 Azerbaijani delegation to highlight Nagorno-Karabakh issue at OSCE PA winter session (February 3, 2008) ............................................................................................................................................... 17 On this night they had no right even to live (February 14, 2008) ...................................................... 18 The horror of the night. I witnessed the genocide (February 14-19, 2008) ....................................... 21 Turkey`s NGOs appeal to GNAT to recognize khojaly tragedy as genocide (February 13, 2008) ... 22 Azerbaijani ambassador meets chairman of Indonesian Parliament’s House of Representatives (February 15, 2008) ............................................................................................................................ 23 Anniversary of Khojaly genocide marked at Indonesian Institute of Sciences (February 18, 2008). 24 Round table on Khojaly genocide held in Knesset (February 20, 2008) ........................................... 25 Their only «fault» was being Azerbaijanis (February -

Constitution-Making in the Informal Soviet Empire in Eastern Europe, East Asia, and Inner Asia, 1945–19551

Constitution-Making in the Informal Soviet Empire in Eastern Europe, East Asia, and Inner Asia, 1945–19551 Ivan Sablin Heidelberg University Abstract This chapter provides an overview of dependent constitution-making under one-party regimes in Albania, Bulgaria, China, Czechoslovakia, East Germany, Hungary, North Korea, Mongolia, Poland, Romania, and Yugoslavia during the first decade after the Second World War. Employing and further developing the concept of the informal Soviet empire, it discusses the structural adjustments in law and governance in the Soviet dependencies. The chapter outlines the development of the concepts of “people’s republic” and “people’s democracy” and discusses the process of adoption and the authorship of the constitutions. It then compares their texts with attention to sovereignty and political subjectivity, supreme state institutions, and the mentions of the Soviet Union, socialism, and ruling parties. Finally, it surveys the role of nonconstitutional institutions in political practices and their reflection in propaganda. The process of constitution-making followed the imperial logic of hierarchical yet heterogeneous governance, with multiple vernacular and Soviet actors partaking in drafting and adopting the constitutions. The texts ascribed sovereignty and political subjectivity to the people, the toilers, classes, nationalities, and regions, often in different combinations. Most of the constitutions established a parliamentary body as the supreme institution, disregarding separation of powers, and introduced a standing body to perform the supreme functions, including legislation, between parliamentary sessions, which became a key element in the legal adjustment. Some constitutions mentioned socialism, the Soviet Union, and the ruling parties. The standardization of governance in the informal Soviet empire manifested itself in the constitutional documents only partially. -

Vol-20. No. 4,Oct. Dec. 2016.Pmd

ISSN 0971-9318 (JOURNAL OF HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION) NGO in Special Consultative Status with ECOSOC, United Nations Vol. 20 No. October-December 2016 HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES © Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, New Delhi. * All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without first seeking the written permission of the publisher or due acknowledgement. * The views expressed in this Journal are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the opinions or policies of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation. SUBSCRIPTION IN INDIA Single Copy (Individual) : Rs. 500.00 Annual (Individual) : Rs. 1000.00 Institutions : Rs. 1400.00 & Libraries (Annual) OVERSEAS (AIRMAIL) Single Copy : US $ 30.00 UK £ 20.00 Annual (Individual) : US $ 60.00 UK £ 40.00 Institutions : US $ 100.00 & Libraries (Annual) UK £ 70.00 Himalayan and Central Asian Studies is included within the ProQuest products Himalayan and Central Asian Studies is included and abstracted in Worldwide Political Science Abstracts and PAIS International, CSA, USA Subscriptions should be sent by crossed cheque or bank draft in favour of HIMALAYAN RESEARCH AND CULTURAL FOUNDATION, B-6/86, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi - 110029 (India) Printed and published by Prof. K. Warikoo on behalf of the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, B-6/86, Safdarjung Enclave, New Delhi-110029. Distributed by Anamika Publishers & Distributors (P) Ltd, 4697/3, 21-A, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi-110002. Printed at Nagri Printers, Delhi-110032. EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD CONTRIBUTORS HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES HIMALAYAN AND CENTRAL ASIAN STUDIES is a quarterly Journal published by the Himalayan Research and Cultural Foundation, which is a non-governmental, non-profit research, cultural and development facilitative organisation. -

Nancy Najarian Eyes Virginia House Seat

MARCH 15, 2014 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXIV, NO. 34, Issue 4328 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 Petition Underway to Switzerland Appeals ECHR Ruling Governor’s Nominate Writer BERN, Switzerland — The Swiss govern - appealed to the ECHR. On December 17, Council Rejects Akram Aylisli for Nobel ment announced this week it would appeal 2013, the ECHR overturned this conviction BAKU (Armenpress) — A number of international the ruling of the European Court of Human on the grounds of freedom of speech. Superior Court public figures and university professors have signed Rights (ECHR) on December 17, 2013, The International Association of a petition nominating Azerbaijani writer Akram which had overturned the conviction of Genocide and Human Rights Studies Aylisli for the 2014 Peace Nobel Prize, in recogni - Dogu Perinçek for denying the Armenian (IIGHRS), a division of the Zoryan Institute, Pick Berman tion of his “amazing courage in overcoming the Genocide. and the Switzerland-Armenia Association hostility between the peoples of Azerbaijan and The decision was made by the Swiss (SAA) have worked together since Armenia.” Federal Office of Justice to ask the ECHR’s December, along with a team of scholars By Colleen Quinn “Only the voices of famous people can encourage Grand Chamber to review the ruling in and experts in international human rights the two nations to embolden each other and final - order to clarify the scope available to Swiss law, major Armenian organizations and BOSTON (State House News Service) ly to bring to an agreement.