The Natural Catastrophes Handbook an Overview and Jurisdictional Survey of Subrogation Issues in the Disaster Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol

Recreational Access to Agricultural Land: Insurance Issues Martha L. Noble* I. Introduction In the United States, a growing urban and suburban population is seeking rural recreational opportunities.^ At the same time, many families involved in traditional agriculture want to diversify and increase the sources of income from their land.^ Both the federal and state govern- ments actively encourage agriculturists to enter land in conservation programs and to increase wildlife habitats on their land.^ In addition, * Staff Attorney, National Center for Agricultural Law Research and Information (NCALRI); Assistant Research Professor, School of Law, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. This material is based upon work supported by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Library under Agreement No. 59-32 U4-8- 13. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this pubUcation are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the USDA or the NCALRI. 1. See generally Langner, Demand for Outdoor Recreation in the United States: Implications for Private Landowners in the Eastern U.S., in Proceedings from the Conference on: Income Opportuntties for the Prt/ate Landowner Through Man- agement OF Natural Resources and Recreational Access 186 (1990) [hereinafter Pro- ceedings] . 2. A survey of New York State Cooperative Extension county agents and regional specialists indicated that an estimated 700 farm famiUes in the state had actually attempted to develop alternative rural enterprises. An estimated 1,700 farm families were considering starting alternative enterprises or diversifying their farms. Many alternatives involved recreational access to the land, including the addition of pick-your-own fruit and vegetable operations, petting zoos, bed and breakfast facilities, and the provision of campgrounds, ski trails, farm tours, and hay rides on farm property. -

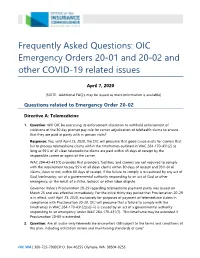

Frequently Asked Questions About Emergency Order 2020-1 and 2020-2

OFFICE of the INSURANCE COMMISSIONER WASHINGTON STATE Frequently Asked Questions: OIC Emergency Orders 20-01 and 20-02 and other COVID-19 related issues April 7, 2020 (NOTE: Additional FAQ’s may be issued as more information is available) Questions related to Emergency Order 20-02 Directive A: Telemedicine 1. Question: Will OIC be exercising its enforcement discretion to withhold enforcement of violations of the 30 day prompt pay rule for carrier adjudication of telehealth claims to ensure that they are paid at parity with in-person visits? Response: Yes, until April 25, 2020, the OIC will presume that good cause exists for carriers that fail to process telemedicine claims within the timeframes outlined in WAC 284-170-431(2) as long as 95% of all clean telemedicine claims are paid within 45 days of receipt by the responsible carrier or agent of the carrier. WAC 284-43-431(7) provides that providers, facilities, and carriers are not required to comply with the requirement to pay 95% of all clean claims within 30 days of receipt and 95% of all claims, clean or not, within 60 days of receipt, if the failure to comply is occasioned by any act of God, bankruptcy, act of a governmental authority responding to an act of God or other emergency, or the result of a strike, lockout, or other labor dispute. Governor Inslee’s Proclamation 20-29 regarding telemedicine payment parity was issued on March 25 and was effective immediately. For the initial thirty day period that Proclamation 20-29 is in effect, until April 25, 2020, exclusively for purposes of payment of telemedicine claims in compliance with Proclamation 20-29, OIC will presume that a failure to comply with the timeframes in WAC 284-170-431(2)(a)(i-ii) is caused by an act of a governmental authority responding to an emergency under WAC 284-170-431(7). -

Is COVID-19 an Act of God And/Or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi

ALERT Corporate Practice MAY 2020 Is COVID-19 an Act of God and/or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi This is the second in a series of alerts on Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses against failure to perform contracts. In our first alert, we discussed the elements of a force majeure clause and looked at how various states have interpreted force majeure clauses. We focused on how most states take a narrow view of these provisions and they adhere to the plain meaning of the force majeure provisions. This alert takes a look at one event often listed in force majeure clauses – Acts of God. As discussed in our previous alert, some courts will excuse performance of a contract only if the event causing the breach is actually listed in the force majeure clause. Among the list of events that would most likely excuse a failure to perform under a contract due to COVID-19 would be if the force majeure provision listed pandemics, epidemic, health emergencies or government orders or regulations. While your contract may not list these events, most force majeure provisions do include an Act of God. In this alert we look at whether it is likely that courts will find that COVID-19 is an Act of God and if such consideration will actually be a defense against performance of a contract. In general, courts have found that an Act of God is a natural event that would not occur by the intervention of man, but proceeds from physical causes. -

Force Majeure and COVID-19

Force Majeure and COVID-19 Not all “Acts of God” are Created Equal Alec W. Farr 1 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Civil law concept written into contracts. • A “force majeure” is an adverse event outside the control of the parties that prevents a party from fulfilling a contract. – Also called an “Act of God” clause • Purpose: to limit damages in a case where the reasonable expectation of the parties and the performance of the contract have been frustrated by circumstances beyond the parties’ control. • Generally only excuses performance if it renders performance impossible, not merely harder or more expensive. • Highly dependent on the specific language of the contract and the circumstances of the case -- one size does not fit all. 2 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Primary issue in determining whether a force majeure clause is applicable: does it list the specific type of event claimed, i.e. a “pandemic” or “epidemic”, as a force majeure event? • Force majeure clauses are interpreted narrowly. • Force majeure event must be the proximate cause of a party’s inability to perform. • The party seeking to invoke force majeure usually must show that it tried to perform. 3 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Most clauses include a general reference to “Acts of God” • What is an “Act of God”? • Usually means an event outside human control that is so extraordinary and unprecedented as to be unforeseeable. • Most often invoked in cases of natural disasters -- earthquakes, floods, extraordinary weather events, etc. • But not all “Acts of God” are necessarily unforeseeable events that will excuse performance of the contract. -

Cargo Insurance What You Need to Know

Cargo Insurance What You Need to Know Making it easier for you Making it easier for you. Is Your Company Exposed? The rigors of international transit can expose your freight to a number of perils. Fires, collisions, storms, accidents, theft, quarantine, civil unrest and many other factors can result in lost or damaged freight and lead to major financial losses for your company. Reilly International wants you to know the risks and the liabilities, so you can make an informed decision about protecting your freight and safeguarding your company’s financial health. The Limits of Carrier Liability The “General Average” Loss It may surprise you to learn that carriers are not In some situations, you may be financially responsible even necessarily liable for your freight while it is in their if your freight was not lost or damaged. General Average possession. Whether ocean, air, truck or rail, there are refers to a partial ocean marine loss. It is determined when myriad situations where carriers can, and do, deny there is a voluntary sacrifice, e.g. jettisoning cargo or liability. At best, without insurance, you’re in for a long extinguishing a fire, in order to save cargo, vessel or life. and complicated legal process. In many cases, the carrier In a General Average, the loss to vessel and freight is will claim no responsibility and your company will have to identified. The financial burden is then divided between all cover the entire loss. the cargo owners. Your cargo is seized until your company Even if the carrier is found to be negligent, the maximum posts a General Average guarantee. -

Pakistan Overwhelmed by Quake Crisis

ITIJITIJ Page 22 Page 26 Page 28 Page 30 International Travel Insurance Journal ISSUE 58 • NOVEMBER 2005 ESSENTIAL READING FOR TRAVEL INSURANCE INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS Europe panics at Pakistan overwhelmed by quake crisis avian flu threat On 8 October, a massive earthquake rocked Pakistan and northern India, The deadly strain of bird flu that has killed resulting in the extensive destruction of approximately 60 people in Asia has spread to property and the loss of thousands of Europe and the continent is in panic. Leonie lives. Initial estimates suggested that at Bennett reports on what is being done to stem the least 33,000 persons perished, now it spread of the virus seems this number is more likely to be around 80,000. Leonie Bennett reports On 13 October, scientists confirmed that the bird flu virus was found in poultry in Turkey, the first time Most of the casualties from the that the virus has been found outside Asia, marking earthquake, which measured 7.6 on the a new phase in the virus’s spread across the globe. Richter scale, were from Pakistan. The Then, on the 17 October, it was established that epicentre of the quake, which lasted for the virus had infected Romanian birds. It was over a minute, was near Muzzaffarabad, confirmed as the H5N1 strain that it is feared can capital of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, at mutate into a human disease, potentially spiralling 9:20 a.m. Indian Standard Time. Tremors out of control and threatening the lives of millions of were reported in Delhi, Punjab, Jammu, people worldwide. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Radboud Repository PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/157883 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-05 and may be subject to change. Accidental Harm Under (Roman) Civil Law Corjo Jansen Abstract A leading idea under Roman private law and nearly all European legal systems is that an owner has to bear the risk of an accidental loss (casus). An accident is a circumstance for which a third party cannot be blamed (culpa or fault). A person suffering damage from an accident had to bear that damage himself. This idea has been subject to attack throughout history. Every once in a while, it is said that ‘bad luck must be righted’ (‘pech moet weg’). This position has not become the prevailing viewpoint among lawyers. Although it does not seem very realistic, ‘bad luck must be righted’ did form the basis of social security policies of the Netherlands and some other western countries after World War II: social security ‘from womb to tomb’. The scope of social security benefits has been reduced in many countries in the last decades of the twentieth century, because the costs were no longer affordable. The idea that a owner has to bear the risk of casus has withstood the test of time quite well. That accidental harm must be borne by the one suffering it, is legally and morally justifiable. -

State of Arkansas Retail Compendium of Law

STATE OF ARKANSAS RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Prepared by Thomas G. Williams Quattlebaum, Grooms, Tull & Burrow PLLC 111 Center Street Little Rock, AR 72201 Tel: (501) 379-1700 Email: [email protected] www.qgtb.com 2014 USLAW Retail Compendium Of Law TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ARKANSAS JUDICIAL SYSTEM A. Arkansas State Courts 1. Supreme Court 2. Court of Appeals 3. Circuit Courts B. District Courts 1. State District Courts 2. Local District Courts C. Arkansas Federal Courts D. Arkansas State Court Venue Rules 1. Real Property 2. Cause a. Recovery of Fines, Penalties, or Forfeitures b. Actions Against Public Officers c. Actions Upon Official Bonds of Public Officers 3. Government Entities or Officers a. Actions on Behalf of the State b. Actions Involving State Boards, State Commissioners, or State Officers c. Actions Against the State, State Boards, State Commissioners, or State Officers d. Other Actions 4. Actions Against Turnpike Road Companies 5. Contract Actions Against Non-resident Prime Contractors or Subcontractors 6. Actions Against Domestic or Foreign Sureties 7. Medical Injuries 8. All Remaining Civil Actions E. Arkansas Civil Procedure 1. State Court Rules a. No Pre-suit Notice Requirement b. Arkansas Rules of Civil Procedure c. Service of Summons 2. Federal Court Rules a. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Local Rules b. Service of Process c. Filing and Serving Documents d. Motion Requirements F. Statute of Limitations and Repose 1. Statute of Limitations a. Action in Contract b. Action in Tort, Personal Injury c. Action in Tort, Wrongful Death d. Actions to Enforce Written Contracts 2 e. Actions to Enforce Unwritten Contracts f. -

071586 23C3252FAC146.Pdf

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF IOWA No. 07–1586 Filed June 5, 2009 VALERIE KOENIG, Appellant, vs. MARC KOENIG, Appellee. Appeal from the Iowa District Court for Polk County, Robert B. Hanson, Judge. Plaintiff appeals judgment in negligence suit seeking abandonment of the common-law classifications for premises liability. REVERSED. Marc S. Harding, Des Moines, for appellant. Jason T. Madden and Amy R. Teas of Bradshaw, Fowler, Proctor & Fairgrave, P.C., Des Moines, for appellee. 2 APPEL, Justice. The question of whether Iowa should retain the traditional common-law distinction between an invitee and a licensee in premises liability cases has sharply divided this court in recent years. In this case, we hold that the common-law distinction between an invitee and a licensee no longer makes sound policy, unnecessarily complicates our law, and should be abandoned. I. Background Facts and Proceedings. Valerie Koenig visited the home of her son, Marc Koenig, when he was ill in order to care for him and help with household chores. After doing laundry, she fell on a carpet cleaner hose while carrying clothes to a bedroom. As a result of the fall, Valerie was injured and required medical care, including the placement of a plate in her leg. Valerie filed a petition alleging that Marc’s negligent conduct caused her permanent injuries, pain and suffering, loss of function, and substantial medical costs. Marc generally denied her claim and further asserted that Valerie was negligent in connection with the occurrence and that she failed to mitigate her damages. At trial, Valerie offered evidence that Marc was aware that the carpet cleaner hose was broken but did not warn her of the defect. -

Chapter 1 Duty Owed by Landowner, Possessor Or Controller

Chapter 1 Duty Owed by Landowner, Possessor Or Controller Jayme C. Long 1-1 INTRODUCTION Premises liability is a form of negligence where liability attaches to an owner, possessor or controller1 of land for injuries caused by the negligent management of its property.2 The duty is primarily owed to persons entering the land, but is sometimes extended to those off the premises. Just as with “general” negligence, there must be a duty, breach, causation and damages. What often sets premises liability apart from general negligence is the issue of duty. The existence or scope of duty in premises liability actions generally follows traditional negligence principles, but may be limited by a number of factors not necessarily applicable to a garden variety negligence action.3 The issue of duty has evolved over time to reflect the standards of our modern, often complex, society. It has been broadened beyond the historical rigid classifications of “invitee,” “licensee” and “trespasser,” but also limited in its reach by statute and policy. 1. For ease of reference, a controller, possessor and owner of land will at times be collectively referenced as a “landowner,” “owner or possessor.” If the status of the person or entity having an interest in the land is significant, it will be noted. 2. Cal. Civ. Code § 1714(a); Brooks v. Eugene Burger Management Corp., 215 Cal. App. 3d 1611, 1619 (1989); Rowland v. Christian, 69 Cal. 2d 108, 119 (1968). 3. Rowland v. Christian, 69 Cal. 2d 108, 112-13 (1968). CALIFORNIA PREMISES LIABILITY LAW 2015 1 CA_Premises_Liability_Ch01.indd 1 10/31/14 4:30:41 PM Chapter 1 Duty Owed by Landowner, Possessor Or Controller 1-2 DUTY, GENERALLY 1-2:1 Owner, Possessor Or Controller of Land In premises liability actions, a defendant is only liable for the defective or dangerous condition of the property he owns, possesses or controls.4 These limits arose from a practical understanding that a person who owns or possesses property is in the best position to discover and control its dangers, and is often the one who created the dangers in the first place. -

Deforming Tort Reform

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 1990 Book Review: Deforming Tort Reform Joseph A. Page Georgetown University Law Center, [email protected] This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1151 78 Geo. L.J. 649-697 (1990) (reviewing Peter W. Huber, Liability: The Legal Revolution and Its Consequences (1988)) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the Insurance Law Commons, and the Torts Commons BOOK REVIEW Deforming Tort Reform LIABILITY: THE LEGAL REVOLUTION AND ITS CONSEQUENCES. By Peter W. Huber.t New York: Basic Books, Inc., 1988. Pp. 260. $19.95. Reviewed by Joseph A. Page* I. THE MANY MEANINGS OF "TORT REFORM" The storms buffeting the tort system over the past two decades have come in three distinct waves. In the late 1960s, steep increases in the insurance costs incurred by health care providers protecting against negligence claims by patients triggered what came to be known as the "medical malpractice crisis." 1 In the mid-1970s, manufacturers whose liability insurance premi ums suddenly soared raised obstreperous complaints that called public atten tion to the existence of a "product liability crisis."2 Finally, other groups whose activities created risks exposing them to lawsuits found that their lia- t Senior Fellow, Manhattan Institute. * Professor of Law, Georgetown University Law Center. The author wishes to thank his col leagues Bill Vukowich and Mike Gottesman, and Victor E. -

What Is Marine Cargo Insurance?

Trade Risk Guaranty Presents WHAT IS CARGO INSURANCE? The Basics WHAT IS CARGO INSURANCE? | THE BASICS TABLE OF CONTENTS History of Marine Cargo Insurance 3 What is Marine Cargo Insurance? 5 Types of Marine Cargo Insurance 7 All Risk – A Clauses 8 Named Perils – B/C Clauses 10 Types of Marine Cargo Insurance Premium 11 Adjustments Open (Rated) 12 Flat Annual 13 Types of Marine Cargo Insurance Risk 14 Management Options Shipment-by-Shipment 15 CIF 16 Annual 17 Carrier Limit of Liability 18 General Average 19 About Trade Risk Guaranty 21 2 HISTORY OF MARINE CARGO INSURANCE 3000 B.C. Marine cargo insurance has existed in various forms dating back to 3000 BC. The earliest record of cargo insurance is referred to as "bottomry." Bottomry is the advance of money on the security of a vessel to protect against the loss of cargo and was usually set at 20 percent. Bottomry protected traders from debt in the event that cargo was lost. 500 A.D. A marine insurance term that can be traced back to ancient times is General Average. Greek, Phoenician, and Indian traders said, "Let that which has been jettisoned on behalf of all be restored by the contribution of all." and "A collection of the contributions for jettison shall be made when the ship is saved." Justinian, the Eastern Roman emperor, included the following regarding General Average: "When a ship is sunk or wrecked, whatever of his property each owner may have saved, he shall keep it for himself." This concept was widely used throughout the early civilizations.