Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts and Business Interruption Insurance1 2 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frequently Asked Questions About Emergency Order 2020-1 and 2020-2

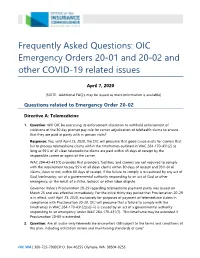

OFFICE of the INSURANCE COMMISSIONER WASHINGTON STATE Frequently Asked Questions: OIC Emergency Orders 20-01 and 20-02 and other COVID-19 related issues April 7, 2020 (NOTE: Additional FAQ’s may be issued as more information is available) Questions related to Emergency Order 20-02 Directive A: Telemedicine 1. Question: Will OIC be exercising its enforcement discretion to withhold enforcement of violations of the 30 day prompt pay rule for carrier adjudication of telehealth claims to ensure that they are paid at parity with in-person visits? Response: Yes, until April 25, 2020, the OIC will presume that good cause exists for carriers that fail to process telemedicine claims within the timeframes outlined in WAC 284-170-431(2) as long as 95% of all clean telemedicine claims are paid within 45 days of receipt by the responsible carrier or agent of the carrier. WAC 284-43-431(7) provides that providers, facilities, and carriers are not required to comply with the requirement to pay 95% of all clean claims within 30 days of receipt and 95% of all claims, clean or not, within 60 days of receipt, if the failure to comply is occasioned by any act of God, bankruptcy, act of a governmental authority responding to an act of God or other emergency, or the result of a strike, lockout, or other labor dispute. Governor Inslee’s Proclamation 20-29 regarding telemedicine payment parity was issued on March 25 and was effective immediately. For the initial thirty day period that Proclamation 20-29 is in effect, until April 25, 2020, exclusively for purposes of payment of telemedicine claims in compliance with Proclamation 20-29, OIC will presume that a failure to comply with the timeframes in WAC 284-170-431(2)(a)(i-ii) is caused by an act of a governmental authority responding to an emergency under WAC 284-170-431(7). -

The Experience of the French Civil Code

NORTH CAROLINA JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW Volume 20 Number 2 Article 3 Winter 1995 Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Oliver Moreleau Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj Recommended Citation Oliver Moreleau, Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code, 20 N.C. J. INT'L L. 273 (1994). Available at: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol20/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Cover Page Footnote International Law; Commercial Law; Law This article is available in North Carolina Journal of International Law: https://scholarship.law.unc.edu/ncilj/vol20/ iss2/3 Codes as Straight-Jackets, Safeguards, and Alibis: The Experience of the French Civil Code Olivier Moriteaut I. Introduction: The Civil Code as a Straight-Jacket? Since 1789, which marked the year of the French Revolution, France has known no fewer than thirteen constitutions.' This fact is scarcely evidence of political stability, although it is fair to say that the Constitution of 1958, of the Fifth Republic, has remained in force for over thirty-five years. On the other hand, the Civil Code (Code), which came into force in 1804, has remained substantially unchanged throughout this entire period. -

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses J. Hunter Robinson† J. Christopher Selman†† Whitt Steineker††† Alexander G. Thrasher†††† Introduction It has been said that, sooner or later, everything old is new again.1 In the wake of the novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) sweeping the globe in 2020, a heretofore largely overlooked and even less understood nineteenth century legal term has come to the forefront of American jurisprudence: force majeure. Force majeure has become a topic du jour in the COVID-19 world with individuals and companies around the world seeking to excuse non- † B.S. (2011), Auburn University; J.D. (2014), Emory University School of Law. Hunter Robinson is an associate at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Hunter is a member of the firm’s litigation and banking and financial services practice groups and represents clients in commercial litigation matters across the country. †† B.S. (2007), Auburn University; J.D. (2012), University of South Carolina School of Law. Chris Selman is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Chris is a members of the firm’s construction and government contracts practice group. He has extensive experience advising clients at every stage of a construction project, managing the resolution of construction disputes domestically and internationally, and drafting and negotiating contracts for a variety of contractor and owner clients. ††† B.A. (2003), University of Alabama; J.D. (2008), Georgetown University Law Center. Whitt Steineker is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Whitt is a member of the firm’s litigation practice group, where he advises clients on a full range of services and routinely represents companies in complex commercial litigation. -

Interview With

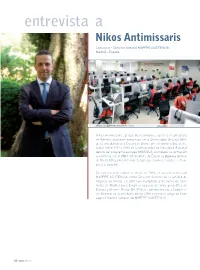

entrevista a Nikos Antimissaris Consejero – Director General MAPFRE ASISTENCIA Madrid – España Contact center de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA en China Nikos Antimissaris, griego de nacimiento, cursó la Licenciatura en Administración de Empresas en la Universidad de Lieja (Bél- gica), vinculándose a España el último año de universidad, al es- tudiar entre 1992 y 1993 en la Universidad de Valladolid (España) dentro del programa europeo ERASMUS. Completó su formación académica con el MBA del Instituto de Empresa Business School, de Madrid (España). Además del griego, domina el inglés, el fran- cés y el español. Su carrera profesional se inició en 1994 en su país natal con MAPFRE ASISTENCIA, como Director General de la Unidad de Negocio de Grecia. En 2001 fue trasladado a los Servicios Cen- trales en Madrid para dirigir el negocio del área geográfica de Europa y Oriente Medio. En 2004 fue promocionado a Subdirec- tor General de la entidad y desde 2006 ostenta el cargo de Con- sejero Director General de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA. 40 / 67 / 2013 667_trebol_esp.indd7_trebol_esp.indd 4040 007/11/137/11/13 001:581:58 “MAPFRE ASISTENCIA aporta una solución integral a sus socios aseguradores que incluye, no sólo la suscripción del riesgo (por la vía del reaseguro), sino también toda la infraestructura operativa para la tramitación de los siniestros y la prestación de los servicios.” Nikos Antimissaris habla siempre en primera persona del plural porque siente que alcanzar en 2013 un volumen de ingresos de mil cien millones de euros es una labor de los seis mil empleados de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA desde los cuarenta y cinco países en que está presente. -

Is COVID-19 an Act of God And/Or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi

ALERT Corporate Practice MAY 2020 Is COVID-19 an Act of God and/or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi This is the second in a series of alerts on Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses against failure to perform contracts. In our first alert, we discussed the elements of a force majeure clause and looked at how various states have interpreted force majeure clauses. We focused on how most states take a narrow view of these provisions and they adhere to the plain meaning of the force majeure provisions. This alert takes a look at one event often listed in force majeure clauses – Acts of God. As discussed in our previous alert, some courts will excuse performance of a contract only if the event causing the breach is actually listed in the force majeure clause. Among the list of events that would most likely excuse a failure to perform under a contract due to COVID-19 would be if the force majeure provision listed pandemics, epidemic, health emergencies or government orders or regulations. While your contract may not list these events, most force majeure provisions do include an Act of God. In this alert we look at whether it is likely that courts will find that COVID-19 is an Act of God and if such consideration will actually be a defense against performance of a contract. In general, courts have found that an Act of God is a natural event that would not occur by the intervention of man, but proceeds from physical causes. -

Force Majeure and Climate Change: What Is the New Normal?

Force majeure and Climate Change: What is the new normal? Jocelyn L. Knoll and Shannon L. Bjorklund1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................2 I. THE SCIENCE OF CLIMATE CHANGE ..................................................................................4 II. FORCE MAJEURE: HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT .........................................................8 III. FORCE MAJEURE IN CONTRACTS ...................................................................................11 A. Defining the Force Majeure Event. ..............................................................................12 B. Additional Contractual Requirements: External Causation, Unavoidability and Notice 15 C. Judicially-Imposed Requirements. ...............................................................................18 1. Foreseeability. .................................................................................................18 2. Ultimate (or external) causation.....................................................................21 D. The Effect of Successfully Invoking a Contractual Force Majeure Provision ............25 E. Force Majeure in the Absence of a Specific Contractual Provision. ...........................25 IV. FORCE MAJEURE PROVISIONS IN STANDARD FORM CONTRACTS AND MANDATORY PROVISIONS FOR GOVERNMENT CONTRACTS ......................................28 A. Standard Form Contracts .............................................................................................28 -

Consent Decree: United States Of

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA ATLANTA DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Civil Action No. 1:00-CV-3142 JTC v. ) ) CONSENT DECREE COLONIAL PIPELINE COMPANY, ) ) Defendant. ) ____________________________________) I. BACKGROUND A. Plaintiff, the United States of America (“United States”), through the Attorney General, at the request of the Administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”), filed a civil complaint (“Complaint”) against Defendant, Colonial Pipeline Company (“Colonial”), pursuant to the Clean Water Act (“CWA”), 33 U.S.C. §§ 1251 et seq., seeking injunctive relief and civil penalties for the discharge of oil into navigable waters of the United States or onto adjoining shorelines. B. The Parties agree that it is desirable to resolve the claims for civil penalties and injunctive relief asserted in the Complaint without further litigation. C. This Consent Decree is entered into between the United States and Colonial for the purpose of settlement and it does not constitute an admission or finding of any violation of federal or state law. This Decree may not be used in any civil proceeding of any type as evidence or proof of any fact or as evidence of the violation of any law, rule, regulation, or Court decision, except in a proceeding to enforce the provisions of this Decree. D. To resolve Colonial’s civil liability for the claims asserted in the Complaint, Colonial will pay a total civil penalty of $34 million to the United States, comply with the injunctive relief requirements in this Consent Decree, and satisfy all other terms of this Consent Decree. -

Force Majeure and COVID-19

Force Majeure and COVID-19 Not all “Acts of God” are Created Equal Alec W. Farr 1 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Civil law concept written into contracts. • A “force majeure” is an adverse event outside the control of the parties that prevents a party from fulfilling a contract. – Also called an “Act of God” clause • Purpose: to limit damages in a case where the reasonable expectation of the parties and the performance of the contract have been frustrated by circumstances beyond the parties’ control. • Generally only excuses performance if it renders performance impossible, not merely harder or more expensive. • Highly dependent on the specific language of the contract and the circumstances of the case -- one size does not fit all. 2 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Primary issue in determining whether a force majeure clause is applicable: does it list the specific type of event claimed, i.e. a “pandemic” or “epidemic”, as a force majeure event? • Force majeure clauses are interpreted narrowly. • Force majeure event must be the proximate cause of a party’s inability to perform. • The party seeking to invoke force majeure usually must show that it tried to perform. 3 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Most clauses include a general reference to “Acts of God” • What is an “Act of God”? • Usually means an event outside human control that is so extraordinary and unprecedented as to be unforeseeable. • Most often invoked in cases of natural disasters -- earthquakes, floods, extraordinary weather events, etc. • But not all “Acts of God” are necessarily unforeseeable events that will excuse performance of the contract. -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Cargo Insurance What You Need to Know

Cargo Insurance What You Need to Know Making it easier for you Making it easier for you. Is Your Company Exposed? The rigors of international transit can expose your freight to a number of perils. Fires, collisions, storms, accidents, theft, quarantine, civil unrest and many other factors can result in lost or damaged freight and lead to major financial losses for your company. Reilly International wants you to know the risks and the liabilities, so you can make an informed decision about protecting your freight and safeguarding your company’s financial health. The Limits of Carrier Liability The “General Average” Loss It may surprise you to learn that carriers are not In some situations, you may be financially responsible even necessarily liable for your freight while it is in their if your freight was not lost or damaged. General Average possession. Whether ocean, air, truck or rail, there are refers to a partial ocean marine loss. It is determined when myriad situations where carriers can, and do, deny there is a voluntary sacrifice, e.g. jettisoning cargo or liability. At best, without insurance, you’re in for a long extinguishing a fire, in order to save cargo, vessel or life. and complicated legal process. In many cases, the carrier In a General Average, the loss to vessel and freight is will claim no responsibility and your company will have to identified. The financial burden is then divided between all cover the entire loss. the cargo owners. Your cargo is seized until your company Even if the carrier is found to be negligent, the maximum posts a General Average guarantee. -

Pakistan Overwhelmed by Quake Crisis

ITIJITIJ Page 22 Page 26 Page 28 Page 30 International Travel Insurance Journal ISSUE 58 • NOVEMBER 2005 ESSENTIAL READING FOR TRAVEL INSURANCE INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS Europe panics at Pakistan overwhelmed by quake crisis avian flu threat On 8 October, a massive earthquake rocked Pakistan and northern India, The deadly strain of bird flu that has killed resulting in the extensive destruction of approximately 60 people in Asia has spread to property and the loss of thousands of Europe and the continent is in panic. Leonie lives. Initial estimates suggested that at Bennett reports on what is being done to stem the least 33,000 persons perished, now it spread of the virus seems this number is more likely to be around 80,000. Leonie Bennett reports On 13 October, scientists confirmed that the bird flu virus was found in poultry in Turkey, the first time Most of the casualties from the that the virus has been found outside Asia, marking earthquake, which measured 7.6 on the a new phase in the virus’s spread across the globe. Richter scale, were from Pakistan. The Then, on the 17 October, it was established that epicentre of the quake, which lasted for the virus had infected Romanian birds. It was over a minute, was near Muzzaffarabad, confirmed as the H5N1 strain that it is feared can capital of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, at mutate into a human disease, potentially spiralling 9:20 a.m. Indian Standard Time. Tremors out of control and threatening the lives of millions of were reported in Delhi, Punjab, Jammu, people worldwide. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Radboud Repository PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/157883 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-05 and may be subject to change. Accidental Harm Under (Roman) Civil Law Corjo Jansen Abstract A leading idea under Roman private law and nearly all European legal systems is that an owner has to bear the risk of an accidental loss (casus). An accident is a circumstance for which a third party cannot be blamed (culpa or fault). A person suffering damage from an accident had to bear that damage himself. This idea has been subject to attack throughout history. Every once in a while, it is said that ‘bad luck must be righted’ (‘pech moet weg’). This position has not become the prevailing viewpoint among lawyers. Although it does not seem very realistic, ‘bad luck must be righted’ did form the basis of social security policies of the Netherlands and some other western countries after World War II: social security ‘from womb to tomb’. The scope of social security benefits has been reduced in many countries in the last decades of the twentieth century, because the costs were no longer affordable. The idea that a owner has to bear the risk of casus has withstood the test of time quite well. That accidental harm must be borne by the one suffering it, is legally and morally justifiable.