The Experience of the French Civil Code

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses

Use the Force? Understanding Force Majeure Clauses J. Hunter Robinson† J. Christopher Selman†† Whitt Steineker††† Alexander G. Thrasher†††† Introduction It has been said that, sooner or later, everything old is new again.1 In the wake of the novel coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) sweeping the globe in 2020, a heretofore largely overlooked and even less understood nineteenth century legal term has come to the forefront of American jurisprudence: force majeure. Force majeure has become a topic du jour in the COVID-19 world with individuals and companies around the world seeking to excuse non- † B.S. (2011), Auburn University; J.D. (2014), Emory University School of Law. Hunter Robinson is an associate at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Hunter is a member of the firm’s litigation and banking and financial services practice groups and represents clients in commercial litigation matters across the country. †† B.S. (2007), Auburn University; J.D. (2012), University of South Carolina School of Law. Chris Selman is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Chris is a members of the firm’s construction and government contracts practice group. He has extensive experience advising clients at every stage of a construction project, managing the resolution of construction disputes domestically and internationally, and drafting and negotiating contracts for a variety of contractor and owner clients. ††† B.A. (2003), University of Alabama; J.D. (2008), Georgetown University Law Center. Whitt Steineker is a partner at Bradley Arant Boult Cummings LLP. Whitt is a member of the firm’s litigation practice group, where he advises clients on a full range of services and routinely represents companies in complex commercial litigation. -

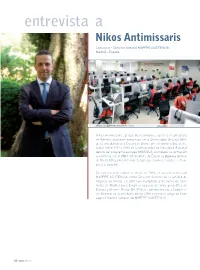

Interview With

entrevista a Nikos Antimissaris Consejero – Director General MAPFRE ASISTENCIA Madrid – España Contact center de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA en China Nikos Antimissaris, griego de nacimiento, cursó la Licenciatura en Administración de Empresas en la Universidad de Lieja (Bél- gica), vinculándose a España el último año de universidad, al es- tudiar entre 1992 y 1993 en la Universidad de Valladolid (España) dentro del programa europeo ERASMUS. Completó su formación académica con el MBA del Instituto de Empresa Business School, de Madrid (España). Además del griego, domina el inglés, el fran- cés y el español. Su carrera profesional se inició en 1994 en su país natal con MAPFRE ASISTENCIA, como Director General de la Unidad de Negocio de Grecia. En 2001 fue trasladado a los Servicios Cen- trales en Madrid para dirigir el negocio del área geográfica de Europa y Oriente Medio. En 2004 fue promocionado a Subdirec- tor General de la entidad y desde 2006 ostenta el cargo de Con- sejero Director General de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA. 40 / 67 / 2013 667_trebol_esp.indd7_trebol_esp.indd 4040 007/11/137/11/13 001:581:58 “MAPFRE ASISTENCIA aporta una solución integral a sus socios aseguradores que incluye, no sólo la suscripción del riesgo (por la vía del reaseguro), sino también toda la infraestructura operativa para la tramitación de los siniestros y la prestación de los servicios.” Nikos Antimissaris habla siempre en primera persona del plural porque siente que alcanzar en 2013 un volumen de ingresos de mil cien millones de euros es una labor de los seis mil empleados de MAPFRE ASISTENCIA desde los cuarenta y cinco países en que está presente. -

Is COVID-19 an Act of God And/Or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi

ALERT Corporate Practice MAY 2020 Is COVID-19 an Act of God and/or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi This is the second in a series of alerts on Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses against failure to perform contracts. In our first alert, we discussed the elements of a force majeure clause and looked at how various states have interpreted force majeure clauses. We focused on how most states take a narrow view of these provisions and they adhere to the plain meaning of the force majeure provisions. This alert takes a look at one event often listed in force majeure clauses – Acts of God. As discussed in our previous alert, some courts will excuse performance of a contract only if the event causing the breach is actually listed in the force majeure clause. Among the list of events that would most likely excuse a failure to perform under a contract due to COVID-19 would be if the force majeure provision listed pandemics, epidemic, health emergencies or government orders or regulations. While your contract may not list these events, most force majeure provisions do include an Act of God. In this alert we look at whether it is likely that courts will find that COVID-19 is an Act of God and if such consideration will actually be a defense against performance of a contract. In general, courts have found that an Act of God is a natural event that would not occur by the intervention of man, but proceeds from physical causes. -

Force Majeure and Climate Change: What Is the New Normal?

Force majeure and Climate Change: What is the new normal? Jocelyn L. Knoll and Shannon L. Bjorklund1 INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................................................................2 I. THE SCIENCE OF CLIMATE CHANGE ..................................................................................4 II. FORCE MAJEURE: HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT .........................................................8 III. FORCE MAJEURE IN CONTRACTS ...................................................................................11 A. Defining the Force Majeure Event. ..............................................................................12 B. Additional Contractual Requirements: External Causation, Unavoidability and Notice 15 C. Judicially-Imposed Requirements. ...............................................................................18 1. Foreseeability. .................................................................................................18 2. Ultimate (or external) causation.....................................................................21 D. The Effect of Successfully Invoking a Contractual Force Majeure Provision ............25 E. Force Majeure in the Absence of a Specific Contractual Provision. ...........................25 IV. FORCE MAJEURE PROVISIONS IN STANDARD FORM CONTRACTS AND MANDATORY PROVISIONS FOR GOVERNMENT CONTRACTS ......................................28 A. Standard Form Contracts .............................................................................................28 -

Consent Decree: United States Of

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF GEORGIA ATLANTA DIVISION UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) Civil Action No. 1:00-CV-3142 JTC v. ) ) CONSENT DECREE COLONIAL PIPELINE COMPANY, ) ) Defendant. ) ____________________________________) I. BACKGROUND A. Plaintiff, the United States of America (“United States”), through the Attorney General, at the request of the Administrator of the United States Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”), filed a civil complaint (“Complaint”) against Defendant, Colonial Pipeline Company (“Colonial”), pursuant to the Clean Water Act (“CWA”), 33 U.S.C. §§ 1251 et seq., seeking injunctive relief and civil penalties for the discharge of oil into navigable waters of the United States or onto adjoining shorelines. B. The Parties agree that it is desirable to resolve the claims for civil penalties and injunctive relief asserted in the Complaint without further litigation. C. This Consent Decree is entered into between the United States and Colonial for the purpose of settlement and it does not constitute an admission or finding of any violation of federal or state law. This Decree may not be used in any civil proceeding of any type as evidence or proof of any fact or as evidence of the violation of any law, rule, regulation, or Court decision, except in a proceeding to enforce the provisions of this Decree. D. To resolve Colonial’s civil liability for the claims asserted in the Complaint, Colonial will pay a total civil penalty of $34 million to the United States, comply with the injunctive relief requirements in this Consent Decree, and satisfy all other terms of this Consent Decree. -

Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses | a National Survey | Shook, Hardy & Bacon

2020 — Force Majeure SHOOK SHB.COM and Common Law Defenses A National Survey APRIL 2020 — Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses A National Survey Contractual force majeure provisions allocate risk of nonperformance due to events beyond the parties’ control. The occurrence of a force majeure event is akin to an affirmative defense to one’s obligations. This survey identifies issues to consider in light of controlling state law. Then we summarize the relevant law of the 50 states and the District of Columbia. 2020 — Shook Force Majeure Amy Cho Thomas J. Partner Dammrich, II 312.704.7744 Partner Task Force [email protected] 312.704.7721 [email protected] Bill Martucci Lynn Murray Dave Schoenfeld Tom Sullivan Norma Bennett Partner Partner Partner Partner Of Counsel 202.639.5640 312.704.7766 312.704.7723 215.575.3130 713.546.5649 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] SHOOK SHB.COM Melissa Sonali Jeanne Janchar Kali Backer Erin Bolden Nott Davis Gunawardhana Of Counsel Associate Associate Of Counsel Of Counsel 816.559.2170 303.285.5303 312.704.7716 617.531.1673 202.639.5643 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Constance Bria Davis Erika Dirk Emily Pedersen Lischen Reeves Associate Associate Associate Associate Associate 816.559.2017 816.559.0397 312.704.7768 816.559.2662 816.559.2056 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Katelyn Romeo Jon Studer Ever Tápia Matt Williams Associate Associate Vergara Associate 215.575.3114 312.704.7736 Associate 415.544.1932 [email protected] [email protected] 816.559.2946 [email protected] [email protected] ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHICAGO | DENVER | HOUSTON | KANSAS CITY | LONDON | LOS ANGELES MIAMI | ORANGE COUNTY | PHILADELPHIA | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TAMPA | WASHINGTON, D.C. -

Application of Force Majeure Under English Law, New York Law and Russian Law (Comparative Analysis)

Application of Force Majeure under English Law, New York Law and Russian Law (Comparative Analysis) April 29, 2020 The current COVID-19 pandemic has, among other issues, highlighted the role of force majeure in commercial contracts. Whether contractual parties are able to rely on the concept of force majeure as grounds to suspend performance of their respective obligations where the performance of relevant obligations has been impeded by a force majeure event, i.e. an unexpected event outside the parties' control (like the COVID-19 outbreak and related governmental emergency measures), will depend on the applicable law and relevant contract provision. In the table below we have briefly commented on the main questions related to application of force majeure under English, New York and Russian law, taking into account the existing COVID-19 situation. Austin Beijing Brussels Dallas Dubai Hong Kong Houston London Moscow New York Palo Alto Riyadh San Francisco Washington bakerbotts.com | Confidential | Copyright© 2020 Baker Botts L.L.P. No. Position under English Law Position under NY Law Position under Russian Law 1. May a party refer to a force majeure event as grounds to suspend performance / be exempt from liability for non- performance if the contract does not contain a force majeure clause? No. No. Generally, yes. There is no independent concept of Under NY law, the presence of an Russian law contains a general statutory rule that a force majeure under English law. A express force majeure clause covering party to a commercial contract may be released from party may only rely on force majeure relevant events in a contract is a liability for non-performance of its obligations if it if it is expressly provided for in a prerequisite for any claim of force proves that performance was impossible due to a contract. -

Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts and Business Interruption Insurance1 2 3

Chicago-Area Small Business Information on COVID-19: Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts and Business Interruption Insurance1 2 3 Businesses across the Chicago area have had their normal operations disrupted by the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic. Illinois is just one of many states that has issued a “stay at home” order, forcing all “non-essential” businesses to close their physical offices.4 While some businesses have been able to continue operating with their employees working remotely, others have been forced to completely or partially suspend operations. The current situation has made it difficult, if not impossible, for many small businesses to meet all of their contractual obligations. This has led some business owners to question whether the COVID-19 pandemic can legally excuse them from performing under these contracts, either temporarily or permanently. This is a complicated legal question with no easy answers, but this handout is intended to serve as a guide to what are known as “force majeure” clauses in contracts. This handout will also briefly discuss whether the COVID-19 pandemic is covered under commonly-held business interruption insurance policies. I. What is Force Majeure? Force majeure is a French term that translates as “superior force.” In the context of contract law, a force majeure clause is a contractually defined event, beyond the control of both parties, which prevents a party from performing under the contract and legally excuses their obligation to perform.5 Depending on the language of the contract and the specific event, a party can be temporarily or permanently excused from performing. Some laypeople colloquially refer to these clauses as “Act of God” provisions. -

Expecting the Unexpected: Responding to Force Majeure and COVID-19

Expecting the Unexpected: Responding to Force Majeure and COVID-19 The battle against COVID-19 has caused There is little case law addressing whether virus-related events implicate force majeure provisions in contracts. disruptions to industries across the US. However, courts historically frown upon force majeure Based on the trajectory of the virus’ impact defenses that are advanced based on economic downturns. in countries like China, Italy and Spain, it For example, a change in circumstances that results in a contract being economically disadvantageous is generally appears inevitable that COVID-19 will continue considered a foreseeable event that is not protected as to affect businesses – both large and small a force majeure event.2 As can already be seen in highly infected locations like San Francisco and New York City, – for the coming weeks and months. Many “non-essential” businesses, including shopping centers, of these businesses are parties to contracts entertainment venues and manufacturers, are being ordered that will become increasingly difficult to to close their doors. In response, we are likely to see an increase in loan defaults, delinquent rents and nonpayment of perform. By now, prudent business owners product orders. As businesses begin to examine COVID-19 as have reviewed their contracts with particular a force majeure event, those that are able to point to defaults resulting from government mandates or labor shortages will attention on each contracts’ force majeure be more successful than those whose claims are based solely clause (if not, resources can be found here on economic hardships. and here). As businesses and their employees Causation plan for this unprecedented time, and react A successful force majeure defense must demonstrate to the unexpected, it is important to keep the the cause and effect of the force majeure event and the 3 following issues in mind. -

Seven Case Law Lessons Regarding Force Majeure and COVID-19

Seven Case Law Lessons regarding Force Majeure and COVID-19 Go to: Background | Excusing Performance | Lesson One – Express Provisions of the Contract | Lesson Two – Supervening Circumstances | Lesson Three – Market Fluctuations | Lesson Four – Temporary Disability | Lesson Five – Partial Disability | Lesson Six – Proving Diligence and Good Faith | Lesson Seven – Limited Certainty | Related Content Current as of: 05/19/2020 by Timothy Murray, Murray, Hogue & Lannis Rather than present a generic laundry list of black letter legal principles, this article posits seven critical lessons that every lawyer should consider in tackling force majeure and COVID-19. It will show that the judicial precedents dealing with past force majeure events provide context and perspective for the current pandemic, in each case contemplating specific circumstances that, if ignored, could lead to perilous results. Background There is a veritable pandemic raging, and I am not referring to COVID-19. It is a pandemic of webinars and legal articles about force majeure and COVID-19. Sadly, no lawyer is immune from it. In force majeure article after article, we are told that the COVID-19 pandemic is unprecedented, but the only thing unprecedented may be the use of the word itself. In fact, there is nothing novel about the novel coronavirus—at least so far as contract law is concerned. Certainly, the scope of the federal and state governments' shutdown of businesses has been unprecedented, causing massive disruptions to the supply chain, prompting innumerable commercial tenants to declare force majeure on their rental obligations, and impelling parties to back out of all manner of deals due to economic uncertainty. -

Transportation Insurance on Contract Liability and Brokers Liability

INSIGHTS March 2018 Transportation Insurance on Contract Liability and Brokers Liability The good news is that because the semi has advanced autopilot there is a 99.9% chance that it is not going to hit us. However, unless we acknowledge and grapple with the changes that are taking place, the transportation insurance industry will miss the opportunity to respond to the evolving needs of both existing and new clients that the semi represents. Looking at the insurance industry as a whole, the financial fundamentals remain weak, with an over-supply of capacity that is being poorly deployed and not generating adequate returns to address the changing risk patterns. Rather than responding to changes in risk by addressing the underlying rating structure, insurers have been moving away from challenging exposures. Meanwhile, emerging technology and the shifting risk profiles that This paper addresses current insurance market challenges autonomous vehicles bring create related to existing and emerging risks in the transportation additional underwriting uncertainty with the backdrop of the reptile industry, including contractual liability, brokers’ liability and the plaintiff philosophy. impact of emerging technology such as artificial intelligence, blockchain and smart contracts. In addition to weak financials, the insurance industry’s product To say that the insurance industry, and in particular the transportation insurance industry, delivery process is highly inefficient, is at a crossroads would be an understatement. The truth of the matter is that the documentation issuance is antiquated transportation insurance industry is at the edge of a cliff and an autonomous electric and ineffective, and our value semi-trailer truck, loaded with 80,000 lbs. -

Cmi International Working Group on General Average

CMI INTERNATIONAL WORKING GROUP ON GENERAL AVERAGE INTRODUCTION At the Plenary Session of the 2012 Beijing Conference the Chairman of the Working Group presented a summary of the deliberations and recommended to the CMI Executive Council “that it should appoint a new International Working Group on General Average, with a mandate to carry out a general review of the York-Antwerp Rules on General Average, and, noting that the York- Antwerp Rules 2004 had not found acceptance in the ship-owning community, to draft a new set of York-Antwerp Rules which meet the requirements of the ship and cargo owners and their respective insurers, with a view to their adoption at the 2016 CMI Conference.” This recommendation was accepted by delegates. Following the Beijing Conference a new IWG was formed consisting of the following members: Bent Nielsen (Denmark) - Chairman Richard Shaw (UK) – Co-rapporteur Taco van der Valk (Netherlands) – Co-rapporteur Andrew Bardot (UK, International Group) Ben Browne (UK) – IUMI Richard Cornah (UK) – AAA Frédéric Denefle (France) Jürgen Hahn (Germany) Michael Harvey (UK) – AMD Linda Howlett (Australia) – ICS Jiro Kubo (Japan) Sveinung Måkestad (Norway) John O’Connor (Canada) Peter Sandell (Finland) Jonathan Spencer (USA) Esteban Vivanco (Argentina) The months following the Beijing Conference the IWG prepared a new questionnaire which was intended to achieve a broad consensus in advance of the 2016 Conference and encourage a general review of all aspects of the York-Antwerp Rules, and was therefore not confined to the issues that had proved to be controversial before and at the Beijing Conference. The questionnaire was distributed as of 15 March 2013 among CMI members (including titulary and consultative members) and two organizations of average adjusters, the Association of Average Adjusters (AAA) and the Association Mondiale de Dispacheurs (AMD).