State of Arizona Retail Compendium of Law

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INDIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol

Recreational Access to Agricultural Land: Insurance Issues Martha L. Noble* I. Introduction In the United States, a growing urban and suburban population is seeking rural recreational opportunities.^ At the same time, many families involved in traditional agriculture want to diversify and increase the sources of income from their land.^ Both the federal and state govern- ments actively encourage agriculturists to enter land in conservation programs and to increase wildlife habitats on their land.^ In addition, * Staff Attorney, National Center for Agricultural Law Research and Information (NCALRI); Assistant Research Professor, School of Law, University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. This material is based upon work supported by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA), National Agricultural Library under Agreement No. 59-32 U4-8- 13. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this pubUcation are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the view of the USDA or the NCALRI. 1. See generally Langner, Demand for Outdoor Recreation in the United States: Implications for Private Landowners in the Eastern U.S., in Proceedings from the Conference on: Income Opportuntties for the Prt/ate Landowner Through Man- agement OF Natural Resources and Recreational Access 186 (1990) [hereinafter Pro- ceedings] . 2. A survey of New York State Cooperative Extension county agents and regional specialists indicated that an estimated 700 farm famiUes in the state had actually attempted to develop alternative rural enterprises. An estimated 1,700 farm families were considering starting alternative enterprises or diversifying their farms. Many alternatives involved recreational access to the land, including the addition of pick-your-own fruit and vegetable operations, petting zoos, bed and breakfast facilities, and the provision of campgrounds, ski trails, farm tours, and hay rides on farm property. -

Personality Rights in Australia1

SWIMMERS, SURFERS, AND SUE SMITH PERSONALITY RIGHTS IN AUSTRALIA1 Therese Catanzariti2 It is somewhat of a misnomer to talk about personality rights in Australia. First, personality rights are not “rights” in the sense of positive rights, a right to do something, or in the sense of proprietary rights, property that can be assigned or mortgaged. Second, personality rights are largely a US law concept, derived from US state law relating to the “right of publicity”. However, it is common commercial practice that Australian performers, actors and sportstars enter endorsement or sponsorship agreements.3 In addition, the Australian Media and Entertainment Arts Alliance, the Australian actors union, insists that the film and television industrial agreements and awards don’t cover merchandising and insist film and television producers enter individual agreements if they want to use an actor’s image in merchandising.4 This paper considers Australian law5 relating to defamation, passing off, and section 52 of the Trade Practices Act,6 draws parallels with US law relating to the right of publicity, and considers whether there is a developing Australian jurisprudence of “personality rights”. Protecting Personality Acknowledging and protecting personality rights protects privacy. But protecting privacy is not the focus and is an unintended incidental. Protecting personality rights protects investment, and has more in common with unfair competition than privacy. Acknowledging and protecting personality rights protects investment in creating and maintaining a carefully manicured public image, an investment of time labour, skill and cash. This includes spin doctors and personal trainers and make-up artists and plastic surgeons and making sure some stories never get into the press. -

The Morality of Strict Liability

THE MORALITY OF STRICT TORT LIABILITY JULES L. COLEMAN* Accidents occur; personal property is damaged and sometimes is lost altogether. Accident victims are likely to suffer anything from mere bruises and headaches to temporary or permanent disability to death. The personal and social costs of accidents are staggering. Yet the question of who should bear these costs has turned the heads of few philosophers and has occasioned surprisingly little philo- sophic discussion. Perhaps that is because the answer has seemed so obvious; accident costs, at least the nontrivial ones, ought to be borne by those at fault in causing them.' The requirement of fault at one time appeared to be so deeply rooted in the concept of per- sonal responsibility that in the famous Ives2 case, Judge Werner was moved to argue that liability without fault was not only immoral, but also an unconstitutional violation of due process of law. Al- * Ph.D., The Rockefeller University; M.S.L., Yale Law School. Associate Professor of Philosophy, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The author wishes to acknowledge the enormous impact that Joel Feinberg and Guido Calabresi have had on the philosophic and legal ideas set forth in this Article, and to express appreciation to Mitchell Polinsky, Bruce Ackerman, and Robert Prichard for their valuable assistance. This Article constitutes part of the author's forthcoming book, RESPONSIBIITY AND Loss ALLOCATION OF THE LAW OF TORTS (Ed.). 1. The term "fault" takes on different shades of meaning, depending upon the legal context in which it is used. For example, the liability of an intentional or reckless tortfeasor is determined differently from that of a negligent tortfeasor. -

Unrealized Torts

Fordham Law School FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History Faculty Scholarship 2002 Unrealized Torts Benjamin C. Zipursky Fordham University School of Law, [email protected] John C.P. Goldberg Harvard Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Benjamin C. Zipursky and John C.P. Goldberg, Unrealized Torts, 88 Va. L. Rev. 1625 (2002) Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/faculty_scholarship/834 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 88 DECEMBER2002 NUMBER 8 ARTICLES UNREALIZED TORTS John C.P. Goldberg*& Benjamin C. Zipursky** INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1626 I. REALIZED WRONGS .................................................................. 1636 A . Crime versus Tort ................................................................ 1636 B. Tort as Civil Recourse ......................................................... 1641 II. WHEN IS HEIGHTENED RISK A COGNIZABLE INJURY? . ..... 1650 III. RISK OF FUTURE INJURY AND THE LAW OF EMOTIONAL D ISTRESS .................................................................................... -

The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La

Louisiana Law Review Volume 22 | Number 1 Symposium: Assumption of Risk Symposium: Insurance Law December 1961 The lP ace of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade Repository Citation John W. Wade, The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence, 22 La. L. Rev. (1961) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol22/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Place of Assumption of Risk in the Law of Negligence John W. Wade* The "doctrine" of assumption of risk is a controversial one, and there is considerable disagreement as to the part which it should play in a negligence case.' On the one hand it has a be- guiling simplicity about it, offering the opportunity of easily disposing of certain cases on a single issue without the need of giving consideration to other, more difficult, issues. On the other hand it overlaps and duplicates certain other doctrines, and its simplicity proves to be misleading because of its failure to point out the policy problems which may be more adequately presented by the other doctrines. Courts disagree as to the scope of the doctrine, some of them confining it to the situation where there is a contractual relation between the parties,2 and others expanding it to any situation in which an action might be brought for negligence.3 Text- writers and commentators commonly criticize the wide applica- tion of the doctrine, and not infrequently suggest that the doc- trine is entirely tautological. -

FTCA Handbook Is a Revision of the Material Originally Published in July 1979 and Updated Periodically Since

JACS-Z 1 November 1999 MEMORANDUM FOR CLAIMS JUDGE ADVOCATES/CLAIMS ATTORNEYS SUBJECT: Federal Tort Claims Act (FTCA) Handbook 1. This edition of the FTCA Handbook is a revision of the material originally published in July 1979 and updated periodically since. The previous edition was last updated in September 1998. This edition contains significant cases through September 1999 pertaining to the filing and processing of administrative claims under the FTCA (Title 28, United States Code, Sections 2671-2680) and related claims statutes. 2. This Handbook provides case citations covering a myriad of issues. The citations are organized in a topical manner, paralleling the steps an attorney should take in analyzing a claim. Older citations have not been removed. Shepardizing is essential. 3. If any errors are noted, including the omission of relevant cases, please use the error sheet at the end of the Handbook to bring this to our attention. Users needing further information or clarification of this material should contact their Area Action Officer or Mr. Joseph H. Rouse, Deputy Chief, Tort Claims Division, DSN: 923-7009, extension 212; or commercial: (301) 677-7009, extension 212. JOHN H. NOLAN III Colonel, JA Commanding TABLE OF CONTENTS I. REQUIREMENTS FOR ADMINISTRATIVE FILING A. Why is There a Requirement? 1. Effective Date of Requirement............................ 1 2. Administrative Filing Requirement Jurisdictional......... 1 3. Waiver of Administrative Filing Requirement.............. 1 4. Purposes of Requirement.................................. 2 5. Administrative Filing Location........................... 2 6. Not Necessary for Compulsory Counterclaim................ 2 7. Not Necessary for Third Party Practice................... 2 B. What Must be Filed? 1. Written Demand for Sum Certain.......................... -

Loss of Consortium Damages

If you have questions or would like further information regarding Loss of Consortium, 175 W. Jackson Blvd., Chicago, IL 60604 please contact: www.querrey.com® Chuck Blackman 312-540-7682 © 2011 Querrey & Harrow, Ltd. All rights reserved. [email protected] ILLINOIS LAW MANUAL CHAPTER XIV DAMAGES C. LOSS OF CONSORTIUM In Illinois, under certain circumstances, an Reiss, 92 Ill. App. 3d 200 (1980); Medley v. injured person’s spouse is entitled to damages for Strong, 200 Ill. App. 3d 488 (1990). “loss of consortium.” I.P.I. 32.04 (2000). Loss of consortium has been defined to include the However, where two persons have a valid support, society, companionship, and sexual marriage under the laws of the state in which they relationship that a husband or wife has been are domiciled, they may still be entitled to a loss deprived of to date, and which he or she is of consortium claim. (People who are domiciled reasonably certain to be deprived of in the future, in Illinois and have crossed state lines for the due to the claimed injury to or death of a spouse. purpose of getting married may not be entitled to Schrock v. Shoemaker, 159 Ill. 2d 533 (1994); recover.) Allen v. Storer, 235 Ill. App. 3d 5 Elliott v. Willis, 92 Ill. 2d 530 (1982); Dini v. (1992). Naiditch, 20 Ill. 2d 406 (1960). The tort of loss of consortium is an action based on an injury to the In a wrongful death action, the surviving personal relationship established by the marriage spouse can recover damages for loss of contract. -

Rail Trespasser Fatalities Federal Railroad Administration Demographic and Behavioral Profiles

U.S. Department of Transportation Rail Trespasser Fatalities Federal Railroad Administration Demographic and Behavioral Profiles June 2013 NOTICE This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for its contents or use thereof. Any opinions, findings and conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Government, nor does mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The U.S. Government assumes no liability for the content or use of the material contained in this document. NOTICE The U.S. Government does not endorse products or manufacturers. Trade or manufacturers’ names appear herein solely because they are considered essential to the objective of this report. NOTE: This report was prepared by North American Management (NAM) at the direction of the Federal Railroad Administration (FRA) for the purpose of more accurately identifying the types of persons who trespass on railroad rights-of-way, and ultimately reducing the number of trespassing casualties, which contribute significantly to the total annual railroad-related deaths and injuries in the United States. This report is an extension of a March 2008 report produced by Cadle Creek Consulting titled, “Rail Trespasser Fatalities, Developing Demographic Profiles” (2008 Report). The entire 2008 Report can be found at http://www.fra.dot.gov/eLib/Details/L02669. The current report was generated as part of FRA’s continuing efforts to reduce trespassing on railroad rights-of-way and associated fatalities and injuries. -

Chapter 668 Liability in Tort — Comparative Fault

1 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT, §668.3 CHAPTER 668 LIABILITY IN TORT — COMPARATIVE FAULT Referred to in §321J.4B, 625.21 668.1 Fault defined. 668.11 Disclosure of expert witnesses 668.2 Party defined. in liability cases involving 668.3 Comparative fault — effect — licensed professionals. payment method. 668.12 Liability for products — defenses. 668.4 Joint and several liability. 668.13 Interest on judgments. Evidence of previous payment or 668.5 Right of contribution. 668.14 future right of payment. 668.6 Enforcement of contribution. 668.14A Recoverable damages for medical 668.7 Effect of release. expenses. 668.8 Tolling of statute. 668.15 Damages resulting from sexual 668.9 Insurance practice. abuse — evidence. 668.10 Governmental exemptions. 668.16 Applicability of this chapter. 668.1 Fault defined. 1. As used in this chapter, “fault” means one or more acts or omissions that are in any measure negligent or reckless toward the person or property of the actor or others, or that subject a person to strict tort liability. The term also includes breach of warranty, unreasonable assumption of risk not constituting an enforceable express consent, misuse of a product for which the defendant otherwise would be liable, and unreasonable failure to avoid an injury or to mitigate damages. 2. The legal requirements of cause in fact and proximate cause apply both to fault as the basis for liability and to contributory fault. 84 Acts, ch 1293, §1 See also §619.17 668.2 Party defined. As used in this chapter, unless otherwise required, “party” means any of the following: 1. -

Slip and Fall.Pdf

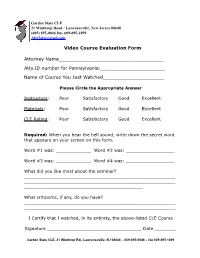

Garden State CLE 21 Winthrop Road • Lawrenceville, New Jersey 08648 (609) 895-0046 fax- 609-895-1899 [email protected] Video Course Evaluation Form Attorney Name____________________________________ Atty ID number for Pennsylvania:______________________ Name of Course You Just Watched_____________________ ! ! Please Circle the Appropriate Answer !Instructors: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent !Materials: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent CLE Rating: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent ! Required: When you hear the bell sound, write down the secret word that appears on your screen on this form. ! Word #1 was: _____________ Word #2 was: __________________ ! Word #3 was: _____________ Word #4 was: __________________ ! What did you like most about the seminar? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ! What criticisms, if any, do you have? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ! I Certify that I watched, in its entirety, the above-listed CLE Course Signature ___________________________________ Date ________ Garden State CLE, 21 Winthrop Rd., Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 – 609-895-0046 – fax 609-895-1899 GARDEN STATE CLE LESSON PLAN A 1.0 credit course FREE DOWNLOAD LESSON PLAN AND EVALUATION WATCH OUT: REPRESENTING A SLIP AND FALL CLIENT Featuring Robert Ramsey Garden State CLE Senior Instructor And Robert W. Rubinstein Certified Civil Trial Attorney Program -

Damien A. Macias V. Summit Management, No

Damien A. Macias v. Summit Management, No. 1130, Sept. Term, 2018 Opinion by Leahy, J. Motion for Summary Judgment > Scope of Review Maryland premises-liability law allows disposition on summary judgment when the pertinent historical facts are not in dispute. See Hansberger v. Smith, 229 Md. App. 1, 13, 21-24 (2016); see also Richardson v. Nwadiuko, 184 Md. App. 481, 483-84 (2009). Negligence > Premises Liability >Foreseeability Foreseeability—the principal consideration in actionable negligence—is not confined to the proximate cause analysis. See Kennedy Krieger Institute, Inc. v. Partlow, 460 Md. 607, 633-34 (2018); Valentine v. On Target, Inc., 112 Md. App. 679, 683-84 (1996), aff'd, 353 Md. 544 (1999). Negligence > Premises Liability >Duty The status of an entrant, and the legal duty owed thereto, are questions of law informed by the historical facts of the case. See Troxel v. Iguana Cantina, LLC, 201 Md. App. 476, 495 (2011). Negligence > Duty to Invitees > Condominium Associations Condominium unit owners and their guests occupy the legal status of invitee when they are in the common areas of the complex over which the condominium association maintains control. Barring any agreements or waivers to the contrary, the condominium association is bound to exercise “reasonable and ordinary care” to keep the premises safe for the invitee and to “protect the invitee from injury caused by an unreasonable risk which the invitee, by exercising ordinary care for his [or her] own safety, will not discover.” See Bramble v. Thompson, 264 Md. 518, 521 (1972). Negligence > Premises Liability >Legal Status An entrant’s legal status is not static and may change through the passage of time or through a change in location. -

State of Delaware Retail Compendium of Law

STATE OF DELAWARE RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Updated in 2017 by Cooch and Taylor 1000 N. West St., 10th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Phone: (302) 984-3800 www.coochtaylor.com 2017 USLAW Retail Compendium of Law TABLE OF CONTENTS The Delaware State Court System ............................................................................... 2-3 Trial Courts ................................................................................................................................................. 2-3 The Justice of the Peace Court .................................................................................................................. 2 The Court of Common Pleas ..................................................................................................................... 2 The Superior Court .................................................................................................................................... 2 The Family Court ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The Chancery Court ................................................................................................................................... 3 Appellate Court ............................................................................................................................................. 3 The Supreme Court of the State of Delaware ........................................................................................... 3 General