The Morality of Strict Liability

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

the Defence of All Reasonable Care I. Canadian

294 ALBERTA LAW REVIEW [VOL. XVIII, NO. 2 . THE DEFENCE OF ALL REASONABLE CARE . even a dog knows the difference between being kicked and being stumbled over.1 I. CANADIAN AUTHORITY Prior to May 1978, there was no clear Canadian authority recognizing the existence of a defence of all reasonable care. For some offences it was necessary that the Crown prove affirmatively beyond a reasonable doubt a mens rea, that is, an intent to commit the offence. For other offences, sometimes called offences of strict or absolute liability, the Crown did not have to prove mens rea, but merely the actus reus. There was no sure and certain method of determining whether an offence was in the first category or the second.2 For example, in R. v. Pierce Fi,sheries3 the Supreme Court of Canada decided that mens rea or proof of knowledge was not required to convict on a charge of having possession of undersized lobsters contrary to regulations made pursuant to the Fisheries Act, R.S.C. 1952, c. 119. But the same court decided that possession of a drug without knowing what it was is no offence.4 In May 1978, the Supreme Court of Canada, with Dickson J. writing for a unanimous court, clearly defined a new category of strict liability offences. This new category does not require the Crown to prove mens rea beyond a reasonable doubt. It allows the defendant to exculpate himself by showing on a balance of probabilities that he took all reasonable care to avoid committing the offence.5 A. -

Crimes Act 2016

REPUBLIC OF NAURU Crimes Act 2016 ______________________________ Act No. 18 of 2016 ______________________________ TABLE OF PROVISIONS PART 1 – PRELIMINARY ....................................................................................................... 1 1 Short title .................................................................................................... 1 2 Commencement ......................................................................................... 1 3 Application ................................................................................................. 1 4 Codification ................................................................................................ 1 5 Standard geographical jurisdiction ............................................................. 2 6 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—ship or aircraft outside Nauru ......................... 2 7 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—transnational crime ......................................... 4 PART 2 – INTERPRETATION ................................................................................................ 6 8 Definitions .................................................................................................. 6 9 Definition of consent ................................................................................ 13 PART 3 – PRINCIPLES OF CRIMINAL RESPONSIBILITY ................................................. 14 DIVISION 3.1 – PURPOSE AND APPLICATION ................................................................. 14 10 Purpose -

Slip and Fall.Pdf

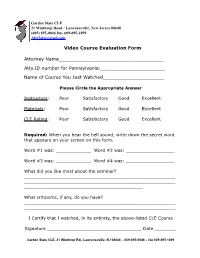

Garden State CLE 21 Winthrop Road • Lawrenceville, New Jersey 08648 (609) 895-0046 fax- 609-895-1899 [email protected] Video Course Evaluation Form Attorney Name____________________________________ Atty ID number for Pennsylvania:______________________ Name of Course You Just Watched_____________________ ! ! Please Circle the Appropriate Answer !Instructors: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent !Materials: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent CLE Rating: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent ! Required: When you hear the bell sound, write down the secret word that appears on your screen on this form. ! Word #1 was: _____________ Word #2 was: __________________ ! Word #3 was: _____________ Word #4 was: __________________ ! What did you like most about the seminar? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ! What criticisms, if any, do you have? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ! I Certify that I watched, in its entirety, the above-listed CLE Course Signature ___________________________________ Date ________ Garden State CLE, 21 Winthrop Rd., Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 – 609-895-0046 – fax 609-895-1899 GARDEN STATE CLE LESSON PLAN A 1.0 credit course FREE DOWNLOAD LESSON PLAN AND EVALUATION WATCH OUT: REPRESENTING A SLIP AND FALL CLIENT Featuring Robert Ramsey Garden State CLE Senior Instructor And Robert W. Rubinstein Certified Civil Trial Attorney Program -

Damien A. Macias V. Summit Management, No

Damien A. Macias v. Summit Management, No. 1130, Sept. Term, 2018 Opinion by Leahy, J. Motion for Summary Judgment > Scope of Review Maryland premises-liability law allows disposition on summary judgment when the pertinent historical facts are not in dispute. See Hansberger v. Smith, 229 Md. App. 1, 13, 21-24 (2016); see also Richardson v. Nwadiuko, 184 Md. App. 481, 483-84 (2009). Negligence > Premises Liability >Foreseeability Foreseeability—the principal consideration in actionable negligence—is not confined to the proximate cause analysis. See Kennedy Krieger Institute, Inc. v. Partlow, 460 Md. 607, 633-34 (2018); Valentine v. On Target, Inc., 112 Md. App. 679, 683-84 (1996), aff'd, 353 Md. 544 (1999). Negligence > Premises Liability >Duty The status of an entrant, and the legal duty owed thereto, are questions of law informed by the historical facts of the case. See Troxel v. Iguana Cantina, LLC, 201 Md. App. 476, 495 (2011). Negligence > Duty to Invitees > Condominium Associations Condominium unit owners and their guests occupy the legal status of invitee when they are in the common areas of the complex over which the condominium association maintains control. Barring any agreements or waivers to the contrary, the condominium association is bound to exercise “reasonable and ordinary care” to keep the premises safe for the invitee and to “protect the invitee from injury caused by an unreasonable risk which the invitee, by exercising ordinary care for his [or her] own safety, will not discover.” See Bramble v. Thompson, 264 Md. 518, 521 (1972). Negligence > Premises Liability >Legal Status An entrant’s legal status is not static and may change through the passage of time or through a change in location. -

State of Delaware Retail Compendium of Law

STATE OF DELAWARE RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Updated in 2017 by Cooch and Taylor 1000 N. West St., 10th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Phone: (302) 984-3800 www.coochtaylor.com 2017 USLAW Retail Compendium of Law TABLE OF CONTENTS The Delaware State Court System ............................................................................... 2-3 Trial Courts ................................................................................................................................................. 2-3 The Justice of the Peace Court .................................................................................................................. 2 The Court of Common Pleas ..................................................................................................................... 2 The Superior Court .................................................................................................................................... 2 The Family Court ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The Chancery Court ................................................................................................................................... 3 Appellate Court ............................................................................................................................................. 3 The Supreme Court of the State of Delaware ........................................................................................... 3 General -

Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt

South Carolina Law Review Volume 57 Issue 2 Article 6 Winter 2005 Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murraywood Swim & (and) Racquet Club and Goode v. St. Stephens United Methodist Church Matthew D. Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, Matthew D. (2005) "Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murraywood Swim & (and) Racquet Club and Goode v. St. Stephens United Methodist Church," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 57 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol57/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lincoln: Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murr LANDOWNERS' DUTY TO GUESTS OF INVITEES AND TENANTS: VOGT V. MURRAYWOOD SWIM & RACQUET CLUB AND GOODE V. ST. STEPHENS UNITED METHODIST CHURCH I. SOUTH CAROLINA ENCOUNTERS THE GUEST ISSUE South Carolina follows traditional premises liability law and defines the duty of care owed by the owner or controller of the premises by reference to categories of entrants, such as invitee and licensee.' A current issue in South Carolina courts is the classification of, and the duty of care owed to, guests of invitees or tenants vis-i-vis the landowner. The issue has presented itself in two scenarios: first, when the guest of a private club member is injured on the club's premises; and second, when the guest of a tenant is injured in the common area of the leased premises. -

Premises Liability - Defense Perspective

PREMISES LIABILITY - DEFENSE PERSPECTIVE Carol Ann Murphy HARRISBURG OFFICE CENTRAL PA OFFICE 3510 Trindle Road MARGOLIS P.O. Box 628 Camp Hill, PA 17011 Hollidaysburg, PA 16648 717-975-8114 EDELSTEIN 814-695-5064 Carol Ann Murphy, Esquire PITTSBURGH OFFICE The Curtis Center, Suite 400E SOUTH JERSEY OFFICE 525 William Penn Place 100 Century Parkway Suite 3300 170 South independence Mall West Suite 200 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Philadelphia, PA 19106-3337 Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 412-281-4256 215-931-5881 856-727-6000 FAX (215) 922-1772 WESTERN PA OFFICE: NORTH JERSEY OFFICE [email protected] 983 Third Street Connell Corporate Center Beaver, PA 15009 400 Connell Drive 724-774-6000 Suite 5400 Berkeley Heights, NJ 07922 SCRANTON OFFICE 908-790-1401 220 Penn Avenue Suite 305 DELAWARE OFFICE: Scranton, PA 18503 750 Shipyard Drive 570-342-4231 Suite 102 Wilmington, DE 19806 302-888-1112 www.margolisedelstein.com PREMISES LIABILITY - DEFENSE PERSPECTIVE In evaluating a case from a defense perspective one must review several issues in determining whether the potential for liability exists. I. STATUS OF CLAIMANT In reviewing a premises liability case, one must determine the status of the claimant. That is, under Pennsylvania law, the determination of the duty of possessor of land toward a third party entering the land depends on whether the entrant is a trespasser, licensee or invitee. Updyke v. BP Oil Company, 717 A.2d 546, 548 (Pa. Super. 1998). A. Trespassers The Restatement (Second) of Torts defined a trespasser as "a person who enters or remains upon land in the possession of another without the privilege to do so created by the possessor's consent or otherwise." Restatement (Second) of Torts § 329. -

Employer Liability for Employee Actions: Derivative Negligence Claims in New Mexico Timothy C. Holm Matthew W. Park Modrall, Sp

Employer Liability for Employee Actions: Derivative Negligence Claims in New Mexico Timothy C. Holm Matthew W. Park Modrall, Sperling, Roehl, Harris & Sisk, P.A. Post Office Box 2168 Bank of America Centre 500 Fourth Street NW, Suite 1000 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103-2168 Telephone: 505.848.1800 Email: [email protected] Every employer is concerned about potential liability for the tortious actions of its employees. Simply stated: Where does an employer’s responsibility for its employee’s actions end, the employee’s personal responsibility begin, and to what extent does accountability overlap? This article is intended to detail the various derivative negligence claims recognized in New Mexico that may impute liability to an employer for its employee’s actions, the elements of each claim, and possible defenses. This subject matter is of particular importance to New Mexico employers generally and transportation employers specifically. A. Elements of Proof for the Derivative Negligent Claim of Negligent Entrustment, Hiring/Retention and Supervision In New Mexico, there are four distinct theories by which an employer might be held to have derivative or dependent liability for the conduct of an employee.1 The definition of derivative or dependent liability is that the employer can be held liable for the fault of the employee in causing to a third party. 1. Respondeat Superior a. What are the elements necessary to establish liability under a theory of Respondeat Superior? An employer is responsible for injury to a third party when its employee commits negligence while acting within the course and scope of his or employment. See McCauley v. -

In Defence of the Due Diligence Defence: a Look at Strict Liability As Sault Ste

In Defence of the Due Diligence Defence: A Look at Strict Liability as Sault Ste. Marie Turns Forty in the Age of Administrative Monetary Penalties by Allison Meredith Sears A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws Faculty of Law University of Toronto © Copyright by Allison Meredith Sears 2018 Defence of the Due Diligence Defence: A Look at Strict Liability as Sault Ste. Marie Turns Forty in the Age of Administrative Monetary Penalties Allison Meredith Sears Master of Laws Faculty of Law University of Toronto 2018 Abstract The author looks back at the Supreme Court of Canada’s creation of a presumption that public welfare offences are strict liability offences affording defendants the opportunity to make out a due diligence defence. It is argued that the availability of this defence is receding in the face of a resurgence of absolute liability by means of administrative monetary penalties, which are increasingly being used by regulators to enforce compliance with regulatory requirements. While there is some support for the availability of the due diligence defence in the face of a potential administrative monetary penalty, the courts remain divided and numerous statutes expressly exclude it. It is argued that this ignores the important function that strict liability offences have served in encouraging corporate social responsibility through the development of compliance programs with the dual purpose of preventing harm and being able to demonstrate the taking of all reasonable care. ii Acknowledgments I would like to thank my thesis supervisor Kent Roach for his helpful guidance and light-handed regulation. -

Duty of Landowner Or Occupier to Firemen Discharging Their Duties

DePaul Law Review Volume 6 Issue 1 Fall-Winter 1956 Article 7 Duty of Landowner or Occupier to Firemen Discharging their Duties DePaul College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation DePaul College of Law, Duty of Landowner or Occupier to Firemen Discharging their Duties, 6 DePaul L. Rev. 97 (1956) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol6/iss1/7 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS DUTY OF LANDOWNER OR OCCUPIER TO FIREMEN DISCHARGING THEIR DUTIES The law places those who come upon the premises of another in three classes: invitees, licensees and trespassers. Upon such classification depends the degree of care that must be exercised toward each by the landowner or occupier.' In the majority of jurisdictions, the rule is that in the absence of a statute or municipal ordinance, a member of a public fire department who, in an emergency, enters a building in the exercise of his duties is a mere licensee under a permission to enter given by law.2 However, there is authority to the effect that a fireman, under certain circumstances, may be considered an invitee.3 As a general rule, a person is a "licensee," as that term is used in the law of negligence, where his entry or use of the premises is permitted, expressly or impliedly, by the owner or person in control thereof.4 The licensee takes the premises as he finds them and the possessor is under no obligation to make the premises safe for his reception. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio Eastern Division

Case: 1:19-cv-00803-PAB Doc #: 31 Filed: 03/29/21 1 of 18. PageID #: <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION CALVIN ADKINS, et al., Case No. 1:19-cv-803 Plaintiff, -vs- JUDGE PAMELA A. BARKER UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, MEMORANDUM OPINION AND Defendants ORDER Currently pending is the Motion for Summary Judgment filed by Defendant United States of America (“the Government”). (Doc. No. 26.) Plaintiff Calvin Adkins (“Adkins”) filed a Memorandum in Opposition, to which the Government replied. (Doc. Nos. 28, 29.) Adkins, with leave of Court, filed a surreply. (Doc. No. 30.) For the following reasons, the Government’s Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED. I. Background This matter stems from an accident at the Akron, Ohio United States Postal Service (“USPS”) facility on May 8, 2016. (Doc. No. 28, PageID# 803.) Plaintiff Calvin Adkins was employed as a truck driver for Thunder Ridge Trucking and transported mail as an independent contractor for the USPS throughout the state of Ohio. (Id.; see also Doc. No. 29, PageID# 827.) Early in the morning on May 8, 2016, Adkins drove to the Akron USPS facility to drop off and pick up mail. (Id.) Adkins waited in the Akron facility near his truck while a USPS employee, Roger Polk (“Polk”), loaded Adkins’s trailer with mail via a forklift. (Doc. No. 26-1, PageID# 108.) According to Adkins, Polk was rushing to load boxes of mail into Adkins’s truck, inadvertently putting the fork through the cardboard boxes of mail as he loaded them. -

State of Arkansas Retail Compendium of Law

STATE OF ARKANSAS RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Prepared by Thomas G. Williams Quattlebaum, Grooms, Tull & Burrow PLLC 111 Center Street Little Rock, AR 72201 Tel: (501) 379-1700 Email: [email protected] www.qgtb.com 2014 USLAW Retail Compendium Of Law TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ARKANSAS JUDICIAL SYSTEM A. Arkansas State Courts 1. Supreme Court 2. Court of Appeals 3. Circuit Courts B. District Courts 1. State District Courts 2. Local District Courts C. Arkansas Federal Courts D. Arkansas State Court Venue Rules 1. Real Property 2. Cause a. Recovery of Fines, Penalties, or Forfeitures b. Actions Against Public Officers c. Actions Upon Official Bonds of Public Officers 3. Government Entities or Officers a. Actions on Behalf of the State b. Actions Involving State Boards, State Commissioners, or State Officers c. Actions Against the State, State Boards, State Commissioners, or State Officers d. Other Actions 4. Actions Against Turnpike Road Companies 5. Contract Actions Against Non-resident Prime Contractors or Subcontractors 6. Actions Against Domestic or Foreign Sureties 7. Medical Injuries 8. All Remaining Civil Actions E. Arkansas Civil Procedure 1. State Court Rules a. No Pre-suit Notice Requirement b. Arkansas Rules of Civil Procedure c. Service of Summons 2. Federal Court Rules a. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Local Rules b. Service of Process c. Filing and Serving Documents d. Motion Requirements F. Statute of Limitations and Repose 1. Statute of Limitations a. Action in Contract b. Action in Tort, Personal Injury c. Action in Tort, Wrongful Death d. Actions to Enforce Written Contracts 2 e. Actions to Enforce Unwritten Contracts f.