Respondeat Superior - Master's Liability to Third Persons Injured As a Result of Accepting an Unauthorized Invitation from the Servant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Morality of Strict Liability

THE MORALITY OF STRICT TORT LIABILITY JULES L. COLEMAN* Accidents occur; personal property is damaged and sometimes is lost altogether. Accident victims are likely to suffer anything from mere bruises and headaches to temporary or permanent disability to death. The personal and social costs of accidents are staggering. Yet the question of who should bear these costs has turned the heads of few philosophers and has occasioned surprisingly little philo- sophic discussion. Perhaps that is because the answer has seemed so obvious; accident costs, at least the nontrivial ones, ought to be borne by those at fault in causing them.' The requirement of fault at one time appeared to be so deeply rooted in the concept of per- sonal responsibility that in the famous Ives2 case, Judge Werner was moved to argue that liability without fault was not only immoral, but also an unconstitutional violation of due process of law. Al- * Ph.D., The Rockefeller University; M.S.L., Yale Law School. Associate Professor of Philosophy, The University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. The author wishes to acknowledge the enormous impact that Joel Feinberg and Guido Calabresi have had on the philosophic and legal ideas set forth in this Article, and to express appreciation to Mitchell Polinsky, Bruce Ackerman, and Robert Prichard for their valuable assistance. This Article constitutes part of the author's forthcoming book, RESPONSIBIITY AND Loss ALLOCATION OF THE LAW OF TORTS (Ed.). 1. The term "fault" takes on different shades of meaning, depending upon the legal context in which it is used. For example, the liability of an intentional or reckless tortfeasor is determined differently from that of a negligent tortfeasor. -

The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: an Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 1987 The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: An Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines Alan O. Sykes Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Alan O. Sykes, "The Boundaries of Vicarious Liability: An Economic Analysis of the Scope of Employment Rule and Related Legal Doctrines," 101 Harvard Law Review 563 (1987). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 101 JANUARY 1988 NUMBER 3 HARVARD LAW REVIEW1 ARTICLES THE BOUNDARIES OF VICARIOUS LIABILITY: AN ECONOMIC ANALYSIS OF THE SCOPE OF EMPLOYMENT RULE AND RELATED LEGAL DOCTRINES Alan 0. Sykes* 441TICARIOUS liability" may be defined as the imposition of lia- V bility upon one party for a wrong committed by another party.1 One of its most common forms is the imposition of liability on an employer for the wrong of an employee or agent. The imposition of vicarious liability usually depends in part upon the nature of the activity in which the wrong arises. For example, if an employee (or "servant") commits a tort within the ordinary course of business, the employer (or "master") normally incurs vicarious lia- bility under principles of respondeat superior. If the tort arises outside the "scope of employment," however, the employer does not incur liability, absent special circumstances. -

Slip and Fall.Pdf

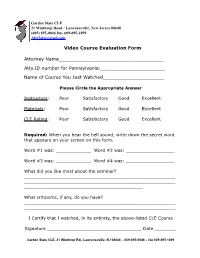

Garden State CLE 21 Winthrop Road • Lawrenceville, New Jersey 08648 (609) 895-0046 fax- 609-895-1899 [email protected] Video Course Evaluation Form Attorney Name____________________________________ Atty ID number for Pennsylvania:______________________ Name of Course You Just Watched_____________________ ! ! Please Circle the Appropriate Answer !Instructors: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent !Materials: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent CLE Rating: Poor Satisfactory Good Excellent ! Required: When you hear the bell sound, write down the secret word that appears on your screen on this form. ! Word #1 was: _____________ Word #2 was: __________________ ! Word #3 was: _____________ Word #4 was: __________________ ! What did you like most about the seminar? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ____________________________________________ ! What criticisms, if any, do you have? ________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________ ! I Certify that I watched, in its entirety, the above-listed CLE Course Signature ___________________________________ Date ________ Garden State CLE, 21 Winthrop Rd., Lawrenceville, NJ 08648 – 609-895-0046 – fax 609-895-1899 GARDEN STATE CLE LESSON PLAN A 1.0 credit course FREE DOWNLOAD LESSON PLAN AND EVALUATION WATCH OUT: REPRESENTING A SLIP AND FALL CLIENT Featuring Robert Ramsey Garden State CLE Senior Instructor And Robert W. Rubinstein Certified Civil Trial Attorney Program -

Damien A. Macias V. Summit Management, No

Damien A. Macias v. Summit Management, No. 1130, Sept. Term, 2018 Opinion by Leahy, J. Motion for Summary Judgment > Scope of Review Maryland premises-liability law allows disposition on summary judgment when the pertinent historical facts are not in dispute. See Hansberger v. Smith, 229 Md. App. 1, 13, 21-24 (2016); see also Richardson v. Nwadiuko, 184 Md. App. 481, 483-84 (2009). Negligence > Premises Liability >Foreseeability Foreseeability—the principal consideration in actionable negligence—is not confined to the proximate cause analysis. See Kennedy Krieger Institute, Inc. v. Partlow, 460 Md. 607, 633-34 (2018); Valentine v. On Target, Inc., 112 Md. App. 679, 683-84 (1996), aff'd, 353 Md. 544 (1999). Negligence > Premises Liability >Duty The status of an entrant, and the legal duty owed thereto, are questions of law informed by the historical facts of the case. See Troxel v. Iguana Cantina, LLC, 201 Md. App. 476, 495 (2011). Negligence > Duty to Invitees > Condominium Associations Condominium unit owners and their guests occupy the legal status of invitee when they are in the common areas of the complex over which the condominium association maintains control. Barring any agreements or waivers to the contrary, the condominium association is bound to exercise “reasonable and ordinary care” to keep the premises safe for the invitee and to “protect the invitee from injury caused by an unreasonable risk which the invitee, by exercising ordinary care for his [or her] own safety, will not discover.” See Bramble v. Thompson, 264 Md. 518, 521 (1972). Negligence > Premises Liability >Legal Status An entrant’s legal status is not static and may change through the passage of time or through a change in location. -

State of Delaware Retail Compendium of Law

STATE OF DELAWARE RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Updated in 2017 by Cooch and Taylor 1000 N. West St., 10th Floor Wilmington, DE 19801 Phone: (302) 984-3800 www.coochtaylor.com 2017 USLAW Retail Compendium of Law TABLE OF CONTENTS The Delaware State Court System ............................................................................... 2-3 Trial Courts ................................................................................................................................................. 2-3 The Justice of the Peace Court .................................................................................................................. 2 The Court of Common Pleas ..................................................................................................................... 2 The Superior Court .................................................................................................................................... 2 The Family Court ....................................................................................................................................... 3 The Chancery Court ................................................................................................................................... 3 Appellate Court ............................................................................................................................................. 3 The Supreme Court of the State of Delaware ........................................................................................... 3 General -

Around Frolic and Detour, a Persistent Problem on the Highway of Torts William A

Campbell Law Review Volume 19 Article 4 Issue 1 Fall 1996 January 1996 Automobile Insurance Policies Build "Write-Away" Around Frolic and Detour, a Persistent Problem on the Highway of Torts William A. Wines Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.campbell.edu/clr Part of the Insurance Law Commons Recommended Citation William A. Wines, Automobile Insurance Policies Build "Write-Away" Around Frolic and Detour, a Persistent Problem on the Highway of Torts, 19 Campbell L. Rev. 85 (1996). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Campbell Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Repository @ Campbell University School of Law. Wines: Automobile Insurance Policies Build "Write-Away" Around Frolic an AUTOMOBILE INSURANCE POLICIES BUILD "WRITE-AWAY" AROUND FROLIC AND DETOUR, A PERSISTENT PROBLEM ON THE HIGHWAY OF TORTS WILLIAM A. WINESt Historians trace the origin of the doctrine of frolic and detour to the pronouncement of Baron Parke in 1834.1 The debate over the wisdom and the theoretical underpinnings of the doctrine seems to have erupted not long after the birth of the doctrine. No less a scholar than Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., questioned whether the doctrine was contrary to common sense.2 This doc- trine continued to attract legal scholars who were still debating the underlying policy premises as the doctrine celebrated its ses- quicentennial and headed toward the second century mark.3 However, the main source of cases which test the doctrine, namely automobile accidents, has started to decline, at least insofar as it involves "frolic and detour" questions and thus the impact of this doctrine may becoming minimized.4 t William A. -

Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt

South Carolina Law Review Volume 57 Issue 2 Article 6 Winter 2005 Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murraywood Swim & (and) Racquet Club and Goode v. St. Stephens United Methodist Church Matthew D. Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Lincoln, Matthew D. (2005) "Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murraywood Swim & (and) Racquet Club and Goode v. St. Stephens United Methodist Church," South Carolina Law Review: Vol. 57 : Iss. 2 , Article 6. Available at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr/vol57/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lincoln: Landowners' Duty to Guests of Invitees and Tenants: Vogt. v. Murr LANDOWNERS' DUTY TO GUESTS OF INVITEES AND TENANTS: VOGT V. MURRAYWOOD SWIM & RACQUET CLUB AND GOODE V. ST. STEPHENS UNITED METHODIST CHURCH I. SOUTH CAROLINA ENCOUNTERS THE GUEST ISSUE South Carolina follows traditional premises liability law and defines the duty of care owed by the owner or controller of the premises by reference to categories of entrants, such as invitee and licensee.' A current issue in South Carolina courts is the classification of, and the duty of care owed to, guests of invitees or tenants vis-i-vis the landowner. The issue has presented itself in two scenarios: first, when the guest of a private club member is injured on the club's premises; and second, when the guest of a tenant is injured in the common area of the leased premises. -

Premises Liability - Defense Perspective

PREMISES LIABILITY - DEFENSE PERSPECTIVE Carol Ann Murphy HARRISBURG OFFICE CENTRAL PA OFFICE 3510 Trindle Road MARGOLIS P.O. Box 628 Camp Hill, PA 17011 Hollidaysburg, PA 16648 717-975-8114 EDELSTEIN 814-695-5064 Carol Ann Murphy, Esquire PITTSBURGH OFFICE The Curtis Center, Suite 400E SOUTH JERSEY OFFICE 525 William Penn Place 100 Century Parkway Suite 3300 170 South independence Mall West Suite 200 Pittsburgh, PA 15219 Philadelphia, PA 19106-3337 Mount Laurel, NJ 08054 412-281-4256 215-931-5881 856-727-6000 FAX (215) 922-1772 WESTERN PA OFFICE: NORTH JERSEY OFFICE [email protected] 983 Third Street Connell Corporate Center Beaver, PA 15009 400 Connell Drive 724-774-6000 Suite 5400 Berkeley Heights, NJ 07922 SCRANTON OFFICE 908-790-1401 220 Penn Avenue Suite 305 DELAWARE OFFICE: Scranton, PA 18503 750 Shipyard Drive 570-342-4231 Suite 102 Wilmington, DE 19806 302-888-1112 www.margolisedelstein.com PREMISES LIABILITY - DEFENSE PERSPECTIVE In evaluating a case from a defense perspective one must review several issues in determining whether the potential for liability exists. I. STATUS OF CLAIMANT In reviewing a premises liability case, one must determine the status of the claimant. That is, under Pennsylvania law, the determination of the duty of possessor of land toward a third party entering the land depends on whether the entrant is a trespasser, licensee or invitee. Updyke v. BP Oil Company, 717 A.2d 546, 548 (Pa. Super. 1998). A. Trespassers The Restatement (Second) of Torts defined a trespasser as "a person who enters or remains upon land in the possession of another without the privilege to do so created by the possessor's consent or otherwise." Restatement (Second) of Torts § 329. -

Employer Liability for Employee Actions: Derivative Negligence Claims in New Mexico Timothy C. Holm Matthew W. Park Modrall, Sp

Employer Liability for Employee Actions: Derivative Negligence Claims in New Mexico Timothy C. Holm Matthew W. Park Modrall, Sperling, Roehl, Harris & Sisk, P.A. Post Office Box 2168 Bank of America Centre 500 Fourth Street NW, Suite 1000 Albuquerque, New Mexico 87103-2168 Telephone: 505.848.1800 Email: [email protected] Every employer is concerned about potential liability for the tortious actions of its employees. Simply stated: Where does an employer’s responsibility for its employee’s actions end, the employee’s personal responsibility begin, and to what extent does accountability overlap? This article is intended to detail the various derivative negligence claims recognized in New Mexico that may impute liability to an employer for its employee’s actions, the elements of each claim, and possible defenses. This subject matter is of particular importance to New Mexico employers generally and transportation employers specifically. A. Elements of Proof for the Derivative Negligent Claim of Negligent Entrustment, Hiring/Retention and Supervision In New Mexico, there are four distinct theories by which an employer might be held to have derivative or dependent liability for the conduct of an employee.1 The definition of derivative or dependent liability is that the employer can be held liable for the fault of the employee in causing to a third party. 1. Respondeat Superior a. What are the elements necessary to establish liability under a theory of Respondeat Superior? An employer is responsible for injury to a third party when its employee commits negligence while acting within the course and scope of his or employment. See McCauley v. -

Duty of Landowner Or Occupier to Firemen Discharging Their Duties

DePaul Law Review Volume 6 Issue 1 Fall-Winter 1956 Article 7 Duty of Landowner or Occupier to Firemen Discharging their Duties DePaul College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review Recommended Citation DePaul College of Law, Duty of Landowner or Occupier to Firemen Discharging their Duties, 6 DePaul L. Rev. 97 (1956) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/law-review/vol6/iss1/7 This Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Law Review by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. COMMENTS DUTY OF LANDOWNER OR OCCUPIER TO FIREMEN DISCHARGING THEIR DUTIES The law places those who come upon the premises of another in three classes: invitees, licensees and trespassers. Upon such classification depends the degree of care that must be exercised toward each by the landowner or occupier.' In the majority of jurisdictions, the rule is that in the absence of a statute or municipal ordinance, a member of a public fire department who, in an emergency, enters a building in the exercise of his duties is a mere licensee under a permission to enter given by law.2 However, there is authority to the effect that a fireman, under certain circumstances, may be considered an invitee.3 As a general rule, a person is a "licensee," as that term is used in the law of negligence, where his entry or use of the premises is permitted, expressly or impliedly, by the owner or person in control thereof.4 The licensee takes the premises as he finds them and the possessor is under no obligation to make the premises safe for his reception. -

In the United States District Court for the Northern District of Ohio Eastern Division

Case: 1:19-cv-00803-PAB Doc #: 31 Filed: 03/29/21 1 of 18. PageID #: <pageID> IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF OHIO EASTERN DIVISION CALVIN ADKINS, et al., Case No. 1:19-cv-803 Plaintiff, -vs- JUDGE PAMELA A. BARKER UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, MEMORANDUM OPINION AND Defendants ORDER Currently pending is the Motion for Summary Judgment filed by Defendant United States of America (“the Government”). (Doc. No. 26.) Plaintiff Calvin Adkins (“Adkins”) filed a Memorandum in Opposition, to which the Government replied. (Doc. Nos. 28, 29.) Adkins, with leave of Court, filed a surreply. (Doc. No. 30.) For the following reasons, the Government’s Motion for Summary Judgment is DENIED. I. Background This matter stems from an accident at the Akron, Ohio United States Postal Service (“USPS”) facility on May 8, 2016. (Doc. No. 28, PageID# 803.) Plaintiff Calvin Adkins was employed as a truck driver for Thunder Ridge Trucking and transported mail as an independent contractor for the USPS throughout the state of Ohio. (Id.; see also Doc. No. 29, PageID# 827.) Early in the morning on May 8, 2016, Adkins drove to the Akron USPS facility to drop off and pick up mail. (Id.) Adkins waited in the Akron facility near his truck while a USPS employee, Roger Polk (“Polk”), loaded Adkins’s trailer with mail via a forklift. (Doc. No. 26-1, PageID# 108.) According to Adkins, Polk was rushing to load boxes of mail into Adkins’s truck, inadvertently putting the fork through the cardboard boxes of mail as he loaded them. -

State of Arkansas Retail Compendium of Law

STATE OF ARKANSAS RETAIL COMPENDIUM OF LAW Prepared by Thomas G. Williams Quattlebaum, Grooms, Tull & Burrow PLLC 111 Center Street Little Rock, AR 72201 Tel: (501) 379-1700 Email: [email protected] www.qgtb.com 2014 USLAW Retail Compendium Of Law TABLE OF CONTENTS THE ARKANSAS JUDICIAL SYSTEM A. Arkansas State Courts 1. Supreme Court 2. Court of Appeals 3. Circuit Courts B. District Courts 1. State District Courts 2. Local District Courts C. Arkansas Federal Courts D. Arkansas State Court Venue Rules 1. Real Property 2. Cause a. Recovery of Fines, Penalties, or Forfeitures b. Actions Against Public Officers c. Actions Upon Official Bonds of Public Officers 3. Government Entities or Officers a. Actions on Behalf of the State b. Actions Involving State Boards, State Commissioners, or State Officers c. Actions Against the State, State Boards, State Commissioners, or State Officers d. Other Actions 4. Actions Against Turnpike Road Companies 5. Contract Actions Against Non-resident Prime Contractors or Subcontractors 6. Actions Against Domestic or Foreign Sureties 7. Medical Injuries 8. All Remaining Civil Actions E. Arkansas Civil Procedure 1. State Court Rules a. No Pre-suit Notice Requirement b. Arkansas Rules of Civil Procedure c. Service of Summons 2. Federal Court Rules a. Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and Local Rules b. Service of Process c. Filing and Serving Documents d. Motion Requirements F. Statute of Limitations and Repose 1. Statute of Limitations a. Action in Contract b. Action in Tort, Personal Injury c. Action in Tort, Wrongful Death d. Actions to Enforce Written Contracts 2 e. Actions to Enforce Unwritten Contracts f.