Casebook on the Roman Law of Contracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Frequently Asked Questions About Emergency Order 2020-1 and 2020-2

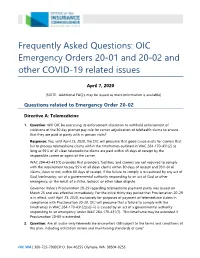

OFFICE of the INSURANCE COMMISSIONER WASHINGTON STATE Frequently Asked Questions: OIC Emergency Orders 20-01 and 20-02 and other COVID-19 related issues April 7, 2020 (NOTE: Additional FAQ’s may be issued as more information is available) Questions related to Emergency Order 20-02 Directive A: Telemedicine 1. Question: Will OIC be exercising its enforcement discretion to withhold enforcement of violations of the 30 day prompt pay rule for carrier adjudication of telehealth claims to ensure that they are paid at parity with in-person visits? Response: Yes, until April 25, 2020, the OIC will presume that good cause exists for carriers that fail to process telemedicine claims within the timeframes outlined in WAC 284-170-431(2) as long as 95% of all clean telemedicine claims are paid within 45 days of receipt by the responsible carrier or agent of the carrier. WAC 284-43-431(7) provides that providers, facilities, and carriers are not required to comply with the requirement to pay 95% of all clean claims within 30 days of receipt and 95% of all claims, clean or not, within 60 days of receipt, if the failure to comply is occasioned by any act of God, bankruptcy, act of a governmental authority responding to an act of God or other emergency, or the result of a strike, lockout, or other labor dispute. Governor Inslee’s Proclamation 20-29 regarding telemedicine payment parity was issued on March 25 and was effective immediately. For the initial thirty day period that Proclamation 20-29 is in effect, until April 25, 2020, exclusively for purposes of payment of telemedicine claims in compliance with Proclamation 20-29, OIC will presume that a failure to comply with the timeframes in WAC 284-170-431(2)(a)(i-ii) is caused by an act of a governmental authority responding to an emergency under WAC 284-170-431(7). -

Is COVID-19 an Act of God And/Or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi

ALERT Corporate Practice MAY 2020 Is COVID-19 an Act of God and/or Will COVID-19 Be a Defense Against Failure to Perform? Swata Gandhi This is the second in a series of alerts on Force Majeure and Common Law Defenses against failure to perform contracts. In our first alert, we discussed the elements of a force majeure clause and looked at how various states have interpreted force majeure clauses. We focused on how most states take a narrow view of these provisions and they adhere to the plain meaning of the force majeure provisions. This alert takes a look at one event often listed in force majeure clauses – Acts of God. As discussed in our previous alert, some courts will excuse performance of a contract only if the event causing the breach is actually listed in the force majeure clause. Among the list of events that would most likely excuse a failure to perform under a contract due to COVID-19 would be if the force majeure provision listed pandemics, epidemic, health emergencies or government orders or regulations. While your contract may not list these events, most force majeure provisions do include an Act of God. In this alert we look at whether it is likely that courts will find that COVID-19 is an Act of God and if such consideration will actually be a defense against performance of a contract. In general, courts have found that an Act of God is a natural event that would not occur by the intervention of man, but proceeds from physical causes. -

Force Majeure and COVID-19

Force Majeure and COVID-19 Not all “Acts of God” are Created Equal Alec W. Farr 1 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Civil law concept written into contracts. • A “force majeure” is an adverse event outside the control of the parties that prevents a party from fulfilling a contract. – Also called an “Act of God” clause • Purpose: to limit damages in a case where the reasonable expectation of the parties and the performance of the contract have been frustrated by circumstances beyond the parties’ control. • Generally only excuses performance if it renders performance impossible, not merely harder or more expensive. • Highly dependent on the specific language of the contract and the circumstances of the case -- one size does not fit all. 2 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Primary issue in determining whether a force majeure clause is applicable: does it list the specific type of event claimed, i.e. a “pandemic” or “epidemic”, as a force majeure event? • Force majeure clauses are interpreted narrowly. • Force majeure event must be the proximate cause of a party’s inability to perform. • The party seeking to invoke force majeure usually must show that it tried to perform. 3 Force Majeure Clauses Generally • Most clauses include a general reference to “Acts of God” • What is an “Act of God”? • Usually means an event outside human control that is so extraordinary and unprecedented as to be unforeseeable. • Most often invoked in cases of natural disasters -- earthquakes, floods, extraordinary weather events, etc. • But not all “Acts of God” are necessarily unforeseeable events that will excuse performance of the contract. -

Cargo Insurance What You Need to Know

Cargo Insurance What You Need to Know Making it easier for you Making it easier for you. Is Your Company Exposed? The rigors of international transit can expose your freight to a number of perils. Fires, collisions, storms, accidents, theft, quarantine, civil unrest and many other factors can result in lost or damaged freight and lead to major financial losses for your company. Reilly International wants you to know the risks and the liabilities, so you can make an informed decision about protecting your freight and safeguarding your company’s financial health. The Limits of Carrier Liability The “General Average” Loss It may surprise you to learn that carriers are not In some situations, you may be financially responsible even necessarily liable for your freight while it is in their if your freight was not lost or damaged. General Average possession. Whether ocean, air, truck or rail, there are refers to a partial ocean marine loss. It is determined when myriad situations where carriers can, and do, deny there is a voluntary sacrifice, e.g. jettisoning cargo or liability. At best, without insurance, you’re in for a long extinguishing a fire, in order to save cargo, vessel or life. and complicated legal process. In many cases, the carrier In a General Average, the loss to vessel and freight is will claim no responsibility and your company will have to identified. The financial burden is then divided between all cover the entire loss. the cargo owners. Your cargo is seized until your company Even if the carrier is found to be negligent, the maximum posts a General Average guarantee. -

Pakistan Overwhelmed by Quake Crisis

ITIJITIJ Page 22 Page 26 Page 28 Page 30 International Travel Insurance Journal ISSUE 58 • NOVEMBER 2005 ESSENTIAL READING FOR TRAVEL INSURANCE INDUSTRY PROFESSIONALS Europe panics at Pakistan overwhelmed by quake crisis avian flu threat On 8 October, a massive earthquake rocked Pakistan and northern India, The deadly strain of bird flu that has killed resulting in the extensive destruction of approximately 60 people in Asia has spread to property and the loss of thousands of Europe and the continent is in panic. Leonie lives. Initial estimates suggested that at Bennett reports on what is being done to stem the least 33,000 persons perished, now it spread of the virus seems this number is more likely to be around 80,000. Leonie Bennett reports On 13 October, scientists confirmed that the bird flu virus was found in poultry in Turkey, the first time Most of the casualties from the that the virus has been found outside Asia, marking earthquake, which measured 7.6 on the a new phase in the virus’s spread across the globe. Richter scale, were from Pakistan. The Then, on the 17 October, it was established that epicentre of the quake, which lasted for the virus had infected Romanian birds. It was over a minute, was near Muzzaffarabad, confirmed as the H5N1 strain that it is feared can capital of Pakistan-occupied Kashmir, at mutate into a human disease, potentially spiralling 9:20 a.m. Indian Standard Time. Tremors out of control and threatening the lives of millions of were reported in Delhi, Punjab, Jammu, people worldwide. -

PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Radboud Repository PDF hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen The following full text is a publisher's version. For additional information about this publication click this link. http://hdl.handle.net/2066/157883 Please be advised that this information was generated on 2017-12-05 and may be subject to change. Accidental Harm Under (Roman) Civil Law Corjo Jansen Abstract A leading idea under Roman private law and nearly all European legal systems is that an owner has to bear the risk of an accidental loss (casus). An accident is a circumstance for which a third party cannot be blamed (culpa or fault). A person suffering damage from an accident had to bear that damage himself. This idea has been subject to attack throughout history. Every once in a while, it is said that ‘bad luck must be righted’ (‘pech moet weg’). This position has not become the prevailing viewpoint among lawyers. Although it does not seem very realistic, ‘bad luck must be righted’ did form the basis of social security policies of the Netherlands and some other western countries after World War II: social security ‘from womb to tomb’. The scope of social security benefits has been reduced in many countries in the last decades of the twentieth century, because the costs were no longer affordable. The idea that a owner has to bear the risk of casus has withstood the test of time quite well. That accidental harm must be borne by the one suffering it, is legally and morally justifiable. -

What Is Marine Cargo Insurance?

Trade Risk Guaranty Presents WHAT IS CARGO INSURANCE? The Basics WHAT IS CARGO INSURANCE? | THE BASICS TABLE OF CONTENTS History of Marine Cargo Insurance 3 What is Marine Cargo Insurance? 5 Types of Marine Cargo Insurance 7 All Risk – A Clauses 8 Named Perils – B/C Clauses 10 Types of Marine Cargo Insurance Premium 11 Adjustments Open (Rated) 12 Flat Annual 13 Types of Marine Cargo Insurance Risk 14 Management Options Shipment-by-Shipment 15 CIF 16 Annual 17 Carrier Limit of Liability 18 General Average 19 About Trade Risk Guaranty 21 2 HISTORY OF MARINE CARGO INSURANCE 3000 B.C. Marine cargo insurance has existed in various forms dating back to 3000 BC. The earliest record of cargo insurance is referred to as "bottomry." Bottomry is the advance of money on the security of a vessel to protect against the loss of cargo and was usually set at 20 percent. Bottomry protected traders from debt in the event that cargo was lost. 500 A.D. A marine insurance term that can be traced back to ancient times is General Average. Greek, Phoenician, and Indian traders said, "Let that which has been jettisoned on behalf of all be restored by the contribution of all." and "A collection of the contributions for jettison shall be made when the ship is saved." Justinian, the Eastern Roman emperor, included the following regarding General Average: "When a ship is sunk or wrecked, whatever of his property each owner may have saved, he shall keep it for himself." This concept was widely used throughout the early civilizations. -

'Act of God' Defense?

State Bar of Texas Volume 30, Number 2 December 2005 OFFIC ERS: Brian R. Sullivan, Chairman 1201 Spy glass Road, Suite 200 OIL, GAS AND Austin, Texas 78746 (512) 32 7-8111 Arnold J . Johnson, Chairman-Elect 350 Glenborough Drive, Suite 100 ENERGY Houston , Texas 77067 (281) 87 2-3352 Richard D. Watt, Vice Chairman 1010 Lam ar, Suite 1600 RESOURCES Houston , Texas 77002 (713) 650-8100 Michael P. Pearson, Secretary 1401 McKinney Street, Suite 1900 Houston, Texas 77010 (713) 752-4311 Norma Rosner Iacovo, Treasurer 1701 E. Lamar Blvd., Suite 100 Arlington, Texas 76006 (817) 462-1507 Laura H. Burney, Immediate Past Chairman 7801 Broadway, Suite 200 San Antonio, Texas 78209 (210) 821-3377 COUNCIL: TERM EXPIRES 2006 Rod Wetsel, Sweetwater Jay G. Martin, Houston Fabene Welch, Houston TERM EXPIRES 2007 William B. Burford, Midland Tim George, Austin David Roth, San Antonio TERM EXPIRES 2008 Timothy Brown, Houston Michael E. Curry, Midland Jolisa M elton Dobbs, Dallas NEWSLETTER EDITOR: SECTION REPORT Jay G. M artin 3900 Essex Lane Houston, Texas 77027 (713) 439-8439 OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF THE OIL, GAS AND ENERGY RESOURCES LAW SECTION OF THE STATE BAR OF TEXAS COVER PHOTO PROVIDED BY WILL HURRICANE KATRINA FURTHER counter-clockwise winds pushed Lake DEFINE THE “ACT OF GOD” DEFENSE? Pontchartrain's waters southward toward New Orleans. By: Michael Chernekoff and Amy Cowley 1 The levees surrounding New Orleans Jones Walker breached or failed, flooding approximately eighty percent of the city with flood waters I. Introduction up to twenty feet deep.3 Southeast Louisiana and southern Mississippi suffered Hurricane Katrina was perhaps the widespread catastrophic damage. -

Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts and Business Interruption Insurance1 2 3

Chicago-Area Small Business Information on COVID-19: Force Majeure Clauses in Contracts and Business Interruption Insurance1 2 3 Businesses across the Chicago area have had their normal operations disrupted by the COVID-19 (coronavirus) pandemic. Illinois is just one of many states that has issued a “stay at home” order, forcing all “non-essential” businesses to close their physical offices.4 While some businesses have been able to continue operating with their employees working remotely, others have been forced to completely or partially suspend operations. The current situation has made it difficult, if not impossible, for many small businesses to meet all of their contractual obligations. This has led some business owners to question whether the COVID-19 pandemic can legally excuse them from performing under these contracts, either temporarily or permanently. This is a complicated legal question with no easy answers, but this handout is intended to serve as a guide to what are known as “force majeure” clauses in contracts. This handout will also briefly discuss whether the COVID-19 pandemic is covered under commonly-held business interruption insurance policies. I. What is Force Majeure? Force majeure is a French term that translates as “superior force.” In the context of contract law, a force majeure clause is a contractually defined event, beyond the control of both parties, which prevents a party from performing under the contract and legally excuses their obligation to perform.5 Depending on the language of the contract and the specific event, a party can be temporarily or permanently excused from performing. Some laypeople colloquially refer to these clauses as “Act of God” provisions. -

Falling Trees, Flying Limbs & Loud Neighbors

3.0 FALLING TREES, FLYING LIMBS & LOUD NEIGHBORS 3.1 Overview Disaster damage from the heavy rains, ferociously high winds, and flooding manifests in a number of ways. Not uncommonly, objects such as furniture or heavy tree limbs go flying, or trees are uprooted by the storm. This chapter addresses questions regarding those situations in which high winds, heavy rains, or flooding cause uprooted trees, tree limbs, and other like objects to damage persons or property. 3.2 Most Common Issues/Questions • My neighbor’s tree fell into my yard during the disaster. It smashed my fence and took out my landscaping. Can I make my neighbor pay for the fence repairs and landscaping? • What if my neighbor’s tree hits my house? • No trees came down during the disaster, but I’m sick of picking up limbs out of my yard from my neighbor’s tree. I’m worried about the next storm; that tree looks awful. What can I do? • Can I make my neighbor trim the tree branches that hang onto my property? • My neighbors are freaking out after the disaster and want to cut down all their trees. They provide the only shade in my yard. Can I stop my neighbors? • My neighbors had a lot of trees fall on their property. They keep running a chainsaw long after I’ve put my kids to bed. Can I stop them? • The fence between my property and my neighbor’s property is down. Who has to pay to replace it? 3.3 Summary of the Law As a general rule, compensation may not be obtained for losses, damage, or harm suffered as a result of an act of God, which means an occurrence due directly and exclusively to natural causes without human intervention and which no amount of foresight, pain, or care, reasonably exercised, could have prevented. -

The Importance of Cargo Insurance Are You Covered Properly?

Premier Provider of Innovative Insurance and Surety Solutions The importance of Cargo Insurance Are you covered properly? ATLANTA | BOSTON | CHARLESTON | CHICAGO | HOUSTON | LOS ANGELES | MIAMI | NEW YORK | SAN FRANCISCO | SEATTLE | TORONTO “Avalon Risk Management is the officially endorsed provider of Cargo Insurance for the SCTC “ -Special Pricing for Members -Avalon partnering with Great American to provide reliable and comprehensive coverage -All-Risk coverage -Avalon has the authority to handle claims. About Avalon Seattle Toronto Boston Chicago San Francisco New York Los Angeles Atlanta Charleston Houston Miami • Mid-sized insurance broker owned by founding management. • Eleven regional offices located in major North American ports. • Transportation insurance specialists. What you will learn • History and Overview • Need for Insurance • General Average • Basics: Different coverage types • Insuring shipments and Avalon technology • Claims © Avalon Risk Management History & Overview • Traces of Cargo Insurance were found as early as 3000 B.C. – Piracy was also a common event. • By the 17th Century, London was the hub of Cargo Insurance. – Edward Lloyd founded a coffee shop where underwriters and traders discussed insurance transactions. – Underwriters formed “Lloyd’s of London.” © Avalon Risk Management The need for cargo insurance Why Insure? • Rigors of shipping – Loss, damage and theft – General Average (ocean) • Carriers’ liability – Carriers only pay claims when liable – Liability is often limited – Often have improper insurance or insufficient funds • Usually in trucking or warehousing © Avalon Risk Management Ocean shipments Ocean Shipments • In the United States, the Carriage of Goods by Sea Act (COGSA) governs liability for ocean cargo. – Limits recovery to $500 per package or customary freight unit (CFU) when the carrier/NVOCC is negligent. -

Force Majeure

Inside 3Q2020 2......How.In-house.Leaders.Can.Use.Technology.to.Better. Prepare.for.the.Next.Crisis 3......ACC.News 4......Force Majeure:.How.COVID-19.is.Impacting.Contract. Considerations.in.Maryland 7......COBRA.Notice.Litigation:.Heightened.Scrutiny.Likely. in.Troubling.Times 8......Protecting.Your.Trade.Secrets.in.the.COVID-19.Era 9......Board.Leadership FOCUS President’s Message Larry Venturelli Greetings and We hope you were able to take advantage If.you.ever.want.to.share.any. welcome to the of the three series webinar last month- ideas.or.comments.with.the. Q3 2020 newslet- Leveraging LinkedIn to Advance Your board,.here.is.the.current.list. ter! It is hard to Career: A Three-Part Career Development of.officers.and.directors: believe that by Series. The series featured Chris Batz, a the time all of Legal Recruiter of the Lion Group, who Larry.Venturelli—President you are reading provided insightful principles on how Board Members: this newsletter to best showcase your experience on summer will be coming to a close and LinkedIn, how to make the LinkedIn Dan.Smith. President.elect.and.Treasurer the fall season will be upon us. If you are Algorithm work for you and four steps to like me, you continue to work from home LinkedIn Visibility. Many thanks to Chris Kimberly.Neal—Secretary with little travel to the office, along with Batz for providing such great content and Cory.Blumberg gearing up for a virtual start to my kids’ to past Board Member, Ed Paulis, for put- Taren.Butcher. school year. ting us in contact with Chris.