Smit, Alexia Jayne (2010) Broadcasting the Body: Affect, Embodiment and Bodily Excess on Contemporary Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STEPHEN MARK, ACE Editor

STEPHEN MARK, ACE Editor Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. DELILAH (series) Various OWN / Warner Bros. Television EP: Craig Wright, Oprah Winfrey, Charles Randolph-Wright NEXT (series) Various Fox / 20th Century Fox Television EP: Manny Coto, Charlie Gogolak, Glenn Ficarra, John Requa SNEAKY PETE (series) Various Amazon / Sony Pictures Television EP: Blake Masters, Bryan Cranston, Jon Avnet, James Degus GREENLEAF (series) Various OWN / Lionsgate Television EP: Oprah Winfrey, Clement Virgo, Craig Wright HELL ON WHEELS (series) Various AMC / Entertainment One Television EP: Mark Richard, John Wirth, Jeremy Gold BLACK SAILS (series) Various Starz / Platinum Dunes EP: Michael Bay, Jonathan Steinberg, Robert Levine, Dan Shotz LEGENDS (pilot)* David Semel TNT / Fox 21 Prod: Howard Gordon, Jonathan Levin, Cyrus Voris, Ethan Reiff DEFIANCE (series) Various Syfy / Universal Cable Productions Prod: Kevin Murphy GAME OF THRONES** (season 2, ep.10) Alan Taylor HBO EP: Devid Benioff, D.B. Weiss BOSS (pilot* + series) Various Starz / Lionsgate Television EP: Farhad Safinia, Gus Van Sant, THE LINE (pilot) Michael Dinner CBS / CBS Television Studios EP: Carl Beverly, Sarah Timberman CANE (series) Various CBS / ABC Studios Prod: Jimmy Smits, Cynthia Cidre, MASTERS OF SCIENCE FICTION (anthology series) Michael Tolkin ABC / IDT Entertainment Jonathan Frakes Prod: Keith Addis, Sam Egan 3 LBS. (series) Various CBS / The Levinson-Fontana Company Prod: Peter Ocko DEADWOOD (series) Various HBO 2007 ACE Eddie Award Nominee | 2006 ACE Eddie Award Winner Prod: David Milch, Gregg Fienberg, Davis Guggenheim 2005 Emmy Nomination WITHOUT A TRACE (pilot) David Nutter CBS / Warner Bros. Television / Jerry Bruckheimer TV Prod: Jerry Bruckheimer, Hank Steinberg SMALLVILLE (pilot + series) David Nutter (pilot) CW / Warner Bros. -

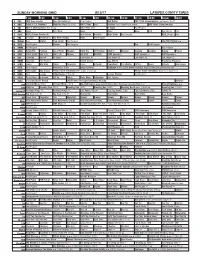

Sunday Morning Grid 8/13/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 8/13/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Bull Riding 2017 PGA Championship Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Triathlon From Kailua-Kona, Hawaii. IAAF World Championships 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid Eye on L.A. Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX In Touch Invitation to Fox News Sunday News Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program The Pink Panther ›› 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program The Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVG) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ KCET Special Å KCET Special Å KCET Special Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI Law Order: CI 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Central Liga MX (N) República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Recuerda y Gana Juego Estrellas Gladiator ››› (2000, Drama Histórico) Russell Crowe, Joaquin Phoenix. -

Printer Friendly Version

RAY COLCORD COMPOSER SELECTED FILMOGRAPHY THE KING'S GUARD – Jonathan Tydor, Director-Shoreline Entertainment Starring Eric Roberts, Ron Perlman and Lesley-Anne Down HEARTWOOD – Lanny Cotler, Director – Porchlight Entertainment/ Lions Gate Releasing Starring Jason Robards and Hilary Swank THE PAPER BRIGADE – Blair Treu, Director -Leucadia Films / Walt Disney Company Starring Kyle Howard, Robert Englund and Bibi Osterwald WISH UPON A STAR – Blair Treu, Director - Leucadia Films / The Walt Disney Company Starring Katherine Heigl and Danielle Harris AMITYVILLE DOLLHOUSE – Steve White, Director -Spectacor Films/ Promark/ Republic Pictures Starring Robin Thomas and Allen Cutler THE SLEEPING CAR – Douglas Curtis - Vidmark Entertainment Starring David Naughton and Kevin McCarthy SONGS ALL DOGS GO TO HEAVEN II (animated film) – Larry Leker and Paul Sabella, Directors -MGM Featuring the voices of Bebe Neuwirth and Charlie Sheen BABES IN TOYLAND (animated film) – Paul Sabella, Director - MGM Featuring the voices of Lacey Chabert, James Belushi and Christopher Plummer EARTH GIRLS ARE EASY (songs) – Julien Temple, Director-Warner Bros. Starring Geena Davis, Jeff Goldblum, Julie Brown and Jim Carrey ("Big & Stupid", "Homecoming Queen's Got A Gun") ADDITIONAL MUSIC LARA CROFT TOMB RAIDER II - Jan de Bont, Director - Paramount Pictures / Mutual Film Company THE GENERAL'S DAUGHTER – Simon West, Director - Paramount Starring John Travolta, Madeleine Stowe, James Cromwell, James Woods and Clarence Williams III DUMB & DUMBER - Peter Farrelly, Director- -

When Victims Rule

1 24 JEWISH INFLUENCE IN THE MASS MEDIA, Part II In 1985 Laurence Tisch, Chairman of the Board of New York University, former President of the Greater New York United Jewish Appeal, an active supporter of Israel, and a man of many other roles, started buying stock in the CBStelevision network through his company, the Loews Corporation. The Tisch family, worth an estimated 4 billion dollars, has major interests in hotels, an insurance company, Bulova, movie theatres, and Loliards, the nation's fourth largest tobacco company (Kent, Newport, True cigarettes). Brother Andrew Tisch has served as a Vice-President for the UJA-Federation, and as a member of the United Jewish Appeal national youth leadership cabinet, the American Jewish Committee, and the American Israel Political Action Committee, among other Jewish organizations. By September of 1986 Tisch's company owned 25% of the stock of CBS and he became the company's president. And Tisch -- now the most powerful man at CBS -- had strong feelings about television, Jews, and Israel. The CBS news department began to live in fear of being compromised by their boss -- overtly, or, more likely, by intimidation towards self-censorship -- concerning these issues. "There have been rumors in New York for years," says J. J. Goldberg, "that Tisch took over CBS in 1986 at least partly out of a desire to do something about media bias against Israel." [GOLDBERG, p. 297] The powerful President of a major American television network dare not publicize his own active bias in favor of another country, of course. That would look bad, going against the grain of the democratic traditions, free speech, and a presumed "fair" mass media. -

The Reel Latina/O Soldier in American War Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-26-2012 12:00 AM The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema Felipe Q. Quintanilla The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Dr. Rafael Montano The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Felipe Q. Quintanilla 2012 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Quintanilla, Felipe Q., "The Reel Latina/o Soldier in American War Cinema" (2012). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 928. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/928 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE REEL LATINA/O SOLDIER IN AMERICAN WAR CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla Graduate Program in Hispanic Studies A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Hispanic Studies The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Felipe Quetzalcoatl Quintanilla 2012 THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies CERTIFICATE OF EXAMINATION Supervisor Examiners ______________________________ -

A Textual Analysis of the Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21St Century Television

A TEXTUAL ANALYSIS OF THE CLOSER AND SAVING GRACE: FEMINIST AND GENRE THEORY IN 21ST CENTURY TELEVISION Lelia M. Stone, B.A., M.P.A. Thesis Prepared for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS December 2013 APPROVED: Harry Benshoff, Committee Chair George Larke-Walsh, Committee Member Sandra Spencer, Committee Member Albert Albarran, Chair of the Department of Radio, Television and Film Art Goven, Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Stone, Lelia M. A Textual Analysis of The Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21st Century Television. Master of Arts (Radio, Television and Film), December 2013, 89 pp., references 82 titles. Television is a universally popular medium that offers a myriad of choices to viewers around the world. American programs both reflect and influence the culture of the times. Two dramatic series, The Closer and Saving Grace, were presented on the same cable network and shared genre and design. Both featured female police detectives and demonstrated an acute awareness of postmodern feminism. The Closer was very successful, yet Saving Grace, was cancelled midway through the third season. A close study of plot lines and character development in the shows will elucidate their fundamental differences that serve to explain their widely disparate reception by the viewing public. Copyright 2013 by Lelia M. Stone ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapters Page 1 INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................. -

NEW RESUME Current-9(5)

DEEDEE BRADLEY CASTING DIRECTOR [email protected] 818-980-9803 X2 TELEVISION PILOTS * Denotes picked up for series SWITCHED AT BIRTH* One hour pilot for ABC Family 2010 Executive Producers: Lizzy Weiss, Paul Stupin Director: Steve Miner BEING HUMAN* One hour pilot for Muse Ent./SyFy 2010 Executive Producers: Jeremy Carver, Anna Fricke, Michael Prupas Director: Adam Kane UNTITLED JUSTIN ADLER PILOT Half hour pilot for Sony/NBC 2009 Executive Producers: Eric Tannenbaum, Kim Tannenbaum, Mitch Hurwitz, Joe Russo, Anthony Russo, Justin Adler, David Guarascio, Moses Port Directors: Joe Russo and Anthony Russo PARTY DOWN * Half hour pilot for STARZ Network 2008 Executive Producers: Rob Thomas, Paul Rudd Director: Rob Thomas BEVERLY HILLS 90210* One hour pilot for CBS/Paramount and CW Network. Executive Producers: Gabe Sachs, Jeff Judah, Mark Piznarski, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski MERCY REEF aka AQUAMAN One hour pilot for Warner Bros./CW 2006 Executive Producers: Miles Millar, Al Gough, Greg Beeman Director : Greg Beeman Shared casting..Joanne Koehler VERONICA MARS* One hour pilot for Stu Segall Productions/UPN 2004 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski SAVING JASON Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./WBN 2003 Executive Producer: Winifred Hervey Director: Stan Lathan NEWTON One hour pilot for Warner Bros/UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Gregory Noveck, Craig Silverstein Director: Lesli Linka Glatter ROCK ME BABY* Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Tony Krantz, Tim Kelleher -

Masterarbeit / Master's Thesis

MASTERARBEIT / MASTER’S THESIS Titel der Masterarbeit / Title of the Master‘s Thesis „Eat the Rude. Serielle Verfahren und die Ästhetisierung kannibalistischer Gewalt in der TV-Serie Hannibal“ verfasst von / submitted by Kristina Höch, BA angestrebter akademischer Grad / in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (MA) Wien, 2016 / Vienna 2016 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt / A 066 582 degree programme code as it appears on the student record sheet: Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt / Masterstudium Theater-, Film- und Medientheorie degree programme as it appears on the student record sheet: Betreut von / Supervisor: Mag. Dr. habil. Ramón Reichert 1 Für meine Eltern. Ihr habt es erst möglich gemacht. Danke für absolut alles! Ihr seid die Besten! Danke Dani, dass du all die Jahre immer für mich da warst. Für all die Zeit, die du in wirre Schachtelsätze investiert hast, für deine aufmunternden Worte und die vielen Care Pakete mit Nervenfutter. Danke Andre, dass du meine Launen ertragen hast und immer an meiner Seite warst, vor allem dann, wenn mich Laptop und Drucker fast in den Wahnsinn getrieben hätten. Danke Johnny, dass du mir bei vielen Kinobesuchen und guten Gesprächen neue Perspektiven eröffnet hast. Ein großer Dank gilt auch Herrn Mag. Dr. habil. Ramón Reichert, der mich durch den Schreibprozess begleitet und mit hilfreichen Tipps und konstruktiver Kritik unterstützt hat. 2 3 Eidesstattliche Erklärung Ich erkläre hiermit an Eides Statt, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne Benutzung anderer als der angegebenen Hilfsmittel angefertigt habe. Die aus fremden Quellen direkt oder indirekt übernommenen Gedanken sind als solche kenntlich gemacht. -

Women Defenders on Television: Representing Suspects and the Racial Politics of Retribution

Women Defenders on Television: Representing Suspects and the Racial Politics of Retribution Joan W. Howarth* I. INTRODUCTION This Essay is about Ellenor Frutt, Annie Dornell, Joyce Davenport, and other women criminal defense attorneys of prime time television. It examines how high-stakes network television presents sympathetic stories about women working as criminal defense attorneys while simultaneously supporting the popular thirst for the harshest criminal penalties. Real women who choose to represent criminal defendants are fundamentally out of step with angry and unforgiving attitudes toward crime and criminals. Indeed, women defenders' have chosen work that puts them in direct opposition to the widespread public willingness to incarcerate record numbers of Americans, often young African- American and Latino men, for longer and longer sentences.2 Their prime time counterparts, however, are creatures of popular taste and conventional ideology, and therefore, perhaps inevitably, readily reinforce rather than resist the popular punitive and racialized incarceration policies. Even the most heroic of the television women defenders support and ratify the dominant public perception of a frightening and irredeemable criminal class-mainly young African-American and Latino men-that requires the harshest and most vengeful sanctions. * Professor of Law, Golden Gate University. I thank the organizers of and participants in this Symposium, and the editors of The Journalof Gender, Race & Justice, especially Amy Weismann. I am very grateful to the various women defenders, friends and strangers, who agreed to tell me about their work. I am especially appreciative of the help I received from Terry Diggs, Kendall Goh, Elizabeth Grossman, Isabelle Gunning, Susan Rutberg, Susan Ten Kwan, Robin Kalman, and Ruth Spear. -

State University of New York at New Paltz Breaking Bad and the Intersection of Critical Theory at Race, Disability, and Gender

Breaking Bad and the intersection of critical theory at race, disability, and gender Item Type Honor's Project Authors McDonough, Matthew Rights Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Download date 01/10/2021 02:24:17 Item License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12648/1578 State University of New York at New Paltz Breaking Bad and the Intersection of Critical Theory at Race, Disability, and Gender Matthew McDonough Independent Study Honors 495-06 Professor Sarah Wyman 8 December 2020 Thesis Abstract: The television series Breaking Bad (created by Vince Gilligan) is considered by audience and critics alike as one of the greatest television series ever made. It tells the story of the rise and fall of Walter White (Bryan Cranston), a mild-mannered chemistry teacher turned meth kingpin. He turns to a life of crime after having been diagnosed with terminal cancer, and he sees meth manufacturing as the most lucrative way to provide for his family. It has been nearly a decade since the series finale, yet it endures through sequel films, spin-offs, and online streaming. My thesis investigates the series’ staying power, and I would argue that lies in its thematic content. Breaking Bad is not just a straightforward story of one man’s descent into a life of crime, but it is also a mediation on dominant, repressive power structures. The series offers a look at these structures through the lens of race, gender, and disability through the actions of characters and their interactions with one another. -

If AJ Liebling Is Correct That

COMMENTS OF THE WRITERS GUILD OF AMERICA REGARDING HARMFUL VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION IN THE TELEVISION INDUSTRY Relating To: CS Docket 98-82: Implementation of Section 11 of the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act of 1992; and CS Docket 96-85: Implementation of the Cable Act Reform Provisions of the Telecommunications Act of 1996; and MM Docket 92-264: The Commission’s Cable Horizontal and Vertical Ownership Limits and Attribution Rules; and MM Docket 94-150: Review of the Commission’s Regulations Governing Attribution of Broadcast and Cable/MDS Interests; and MM Docket 92-51: Review of the Commission’s Regulations and Policies Affecting Investment In the Broadcast Industry; and MM Docket 87-154: Reexamination of the Commission’s Cross-Interest Policy Filed By Charles B. Slocum, January 4, 2002 on behalf of Writers Guild of America, west, Inc. 7000 West Third Street Los Angeles, CA 90048 and Writers Guild of America, East, Inc. 555 West 57th Street New York, NY 10019 If A.J. Liebling is correct that “freedom of the press belongs to the man who owns one” then we have big problems in television… WGA COMMENTS REGARDING HARMFUL VERTICAL AND HORIZONTAL INTEGRATION IN TELEVISION PAGE 1 Vertical and Horizontal Concentration in Television Have Limited Diversity and Creativity The Commission Must Act to Understand the Lack of Competition in the Video Program Market and to Ensure Diversity is Established in the Future Since its creation in 1934, the Federal Communications Commission has been charged with protecting the public interest by regulating the technologies which make mass communications possible. -

Jews and Hollywood

From Shtetl to Stardom: Jews and Hollywood The Jewish Role in American Life An Annual Review of the Casden Institute for the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life From Shtetl to Stardom: Jews and Hollywood The Jewish Role in American Life An Annual Review of the Casden Institute for the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life Volume 14 Steven J. Ross, Editor Michael Renov and Vincent Brook, Guest Editors Lisa Ansell, Associate Editor Published by the Purdue University Press for the USC Casden Institute for the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life © 2017 University of Southern California Casden Institute for the Study of the Jewish Role in American Life. All rights reserved. Production Editor, Marilyn Lundberg Cover photo supplied by Thomas Wolf, www.foto.tw.de, as found on Wikimedia Commons. Front cover vector art supplied by aarows/iStock/Thinkstock. Cloth ISBN: 978-1-55753-763-8 ePDF ISBN: 978-1-61249-478-4 ePUB ISBN: 978-1-61249-479-1 KU ISBN: 978-1-55753-788-1 Published by Purdue University Press West Lafayette, Indiana www.thepress.purdue.edu [email protected] Printed in the United States of America. For subscription information, call 1-800-247-6553 Contents FOREWORD vii EDITORIAL INTRODUCTION ix Michael Renov and Vincent Brook, Guest Editors PART 1: HISTORIES CHAPTER 1 3 Vincent Brook Still an Empire of Their Own: How Jews Remain Atop a Reinvented Hollywood CHAPTER 2 23 Lawrence Baron and Joel Rosenberg, with a Coda by Vincent Brook The Ben Urwand Controversy: Exploring the Hollywood-Hitler Relationship PART 2: CASE STUDIES CHAPTER 3 49 Shaina Hammerman Dirty Jews: Amy Schumer and Other Vulgar Jewesses CHAPTER 4 73 Joshua Louis Moss “The Woman Thing and the Jew Thing”: Transsexuality, Transcomedy, and the Legacy of Subversive Jewishness in Transparent CHAPTER 5 99 Howard A.