An Economic Analysis of the Prime Time Access Rule

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Ownership Chart

In 1983, 50 corporations controlled the vast majority of all news media in the U.S. At the time, Ben Bagdikian was called "alarmist" for pointing this out in his book, The Media Monopoly . In his 4th edition, published in 1992, he wrote "in the U.S., fewer than two dozen of these extraordinary creatures own and operate 90% of the mass media" -- controlling almost all of America's newspapers, magazines, TV and radio stations, books, records, movies, videos, wire services and photo agencies. He predicted then that eventually this number would fall to about half a dozen companies. This was greeted with skepticism at the time. When the 6th edition of The Media Monopoly was published in 2000, the number had fallen to six. Since then, there have been more mergers and the scope has expanded to include new media like the Internet market. More than 1 in 4 Internet users in the U.S. now log in with AOL Time-Warner, the world's largest media corporation. In 2004, Bagdikian's revised and expanded book, The New Media Monopoly , shows that only 5 huge corporations -- Time Warner, Disney, Murdoch's News Corporation, Bertelsmann of Germany, and Viacom (formerly CBS) -- now control most of the media industry in the U.S. General Electric's NBC is a close sixth. Who Controls the Media? Parent General Electric Time Warner The Walt Viacom News Company Disney Co. Corporation $100.5 billion $26.8 billion $18.9 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues $23 billion 1998 revenues $13 billion 1998 revenues 1998 revenues Background GE/NBC's ranks No. -

The 26Th Society for Animation Studies Annual Conference Toronto

Sheridan College SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence The Animator Conferences & Events 6-16-2014 The Animator: The 26th oS ciety for Animation Studies Annual Conference Toronto June 16 to 19, 2014 Society for Animation Studies Paul Ward Society for Animation Studies Tony Tarantini Sheridan College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://source.sheridancollege.ca/conferences_anim Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons SOURCE Citation Society for Animation Studies; Ward, Paul; and Tarantini, Tony, "The Animator: The 26th ocS iety for Animation Studies Annual Conference Toronto June 16 to 19, 2014" (2014). The Animator. 1. http://source.sheridancollege.ca/conferences_anim/1 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences & Events at SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Animator by an authorized administrator of SOURCE: Sheridan Scholarly Output, Research, and Creative Excellence. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THANK YOU TO OUR SPONSORS THE ANIMATOR THEThe 26th Society forANIMATOR Animation Studies Annual Conference TheToronto 26 Juneth Society 16 to 19, 2014 for www.theAnimation animator2014.com Studies @AnimatorSAS2014 Annual Conference Toronto June 16 to 19, 2014 • www.the animator2014.com • @AnimatorSAS2014 WELCOME Message from the President Animation is both an art and skill; it is a talent that is envied the world over. Having a hand in educating and nurturing some of the finest animators in the world is something for which Sheridan is exceptionally proud. -

FCC-06-11A1.Pdf

Federal Communications Commission FCC 06-11 Before the FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION WASHINGTON, D.C. 20554 In the Matter of ) ) Annual Assessment of the Status of Competition ) MB Docket No. 05-255 in the Market for the Delivery of Video ) Programming ) TWELFTH ANNUAL REPORT Adopted: February 10, 2006 Released: March 3, 2006 Comment Date: April 3, 2006 Reply Comment Date: April 18, 2006 By the Commission: Chairman Martin, Commissioners Copps, Adelstein, and Tate issuing separate statements. TABLE OF CONTENTS Heading Paragraph # I. INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................................. 1 A. Scope of this Report......................................................................................................................... 2 B. Summary.......................................................................................................................................... 4 1. The Current State of Competition: 2005 ................................................................................... 4 2. General Findings ....................................................................................................................... 6 3. Specific Findings....................................................................................................................... 8 II. COMPETITORS IN THE MARKET FOR THE DELIVERY OF VIDEO PROGRAMMING ......... 27 A. Cable Television Service .............................................................................................................. -

CLONES, BONES and TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING the DIGITAL PERSONA of the QUICK, the DEAD and the IMAGINARY by Josephj

CLONES, BONES AND TWILIGHT ZONES: PROTECTING THE DIGITAL PERSONA OF THE QUICK, THE DEAD AND THE IMAGINARY By JosephJ. Beard' ABSTRACT This article explores a developing technology-the creation of digi- tal replicas of individuals, both living and dead, as well as the creation of totally imaginary humans. The article examines the various laws, includ- ing copyright, sui generis, right of publicity and trademark, that may be employed to prevent the creation, duplication and exploitation of digital replicas of individuals as well as to prevent unauthorized alteration of ex- isting images of a person. With respect to totally imaginary digital hu- mans, the article addresses the issue of whether such virtual humans should be treated like real humans or simply as highly sophisticated forms of animated cartoon characters. TABLE OF CONTENTS I. IN TR O DU C T IO N ................................................................................................ 1166 II. CLONES: DIGITAL REPLICAS OF LIVING INDIVIDUALS ........................ 1171 A. Preventing the Unauthorized Creation or Duplication of a Digital Clone ...1171 1. PhysicalAppearance ............................................................................ 1172 a) The D irect A pproach ...................................................................... 1172 i) The T echnology ....................................................................... 1172 ii) Copyright ................................................................................. 1176 iii) Sui generis Protection -

Literariness.Org-Mareike-Jenner-Auth

Crime Files Series General Editor: Clive Bloom Since its invention in the nineteenth century, detective fiction has never been more pop- ular. In novels, short stories, films, radio, television and now in computer games, private detectives and psychopaths, prim poisoners and overworked cops, tommy gun gangsters and cocaine criminals are the very stuff of modern imagination, and their creators one mainstay of popular consciousness. Crime Files is a ground-breaking series offering scholars, students and discerning readers a comprehensive set of guides to the world of crime and detective fiction. Every aspect of crime writing, detective fiction, gangster movie, true-crime exposé, police procedural and post-colonial investigation is explored through clear and informative texts offering comprehensive coverage and theoretical sophistication. Titles include: Maurizio Ascari A COUNTER-HISTORY OF CRIME FICTION Supernatural, Gothic, Sensational Pamela Bedore DIME NOVELS AND THE ROOTS OF AMERICAN DETECTIVE FICTION Hans Bertens and Theo D’haen CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN CRIME FICTION Anita Biressi CRIME, FEAR AND THE LAW IN TRUE CRIME STORIES Clare Clarke LATE VICTORIAN CRIME FICTION IN THE SHADOWS OF SHERLOCK Paul Cobley THE AMERICAN THRILLER Generic Innovation and Social Change in the 1970s Michael Cook NARRATIVES OF ENCLOSURE IN DETECTIVE FICTION The Locked Room Mystery Michael Cook DETECTIVE FICTION AND THE GHOST STORY The Haunted Text Barry Forshaw DEATH IN A COLD CLIMATE A Guide to Scandinavian Crime Fiction Barry Forshaw BRITISH CRIME FILM Subverting -

Escuela Politécnica Nacional Facultad De Ingeniería Eléctrica Y Electrónica

ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA NACIONAL FACULTAD DE INGENIERÍA ELÉCTRICA Y ELECTRÓNICA DISEÑO DE LA CABECERA (HEAD END) DE UNA EMPRESA DE CATV PARA PROVEER TELEVISIÓN DE ALTA DEFINICIÓN (HDTV) EN LAS CIUDADES DE QUITO Y GUAYAQUIL UTILIZANDO UNA ARQUITECTURA REDUNDANTE PROYECTO PREVIO A LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE INGENIERO EN ELECTRÓNICA Y TELECOMUNICACIONES LOAIZA FREIRE ALBERTO GABINO [email protected] DIRECTOR: ING. FERNANDO FLORES [email protected] Quito, Noviembre 2011 DECLARACIÓN Yo Alberto Gabino Loaiza Freire, declaró bajo juramento que el trabajo aquí descrito es de mi autoría; que no ha sido previamente presentado para ningún grado o calificación profesional; y, que he consultado las referencias bibliográficas que se incluyen en este documento. A través de la presente declaración cedo mis derechos de propiedad intelectual correspondientes a este trabajo, a la Escuela Politécnica Nacional, según lo establecido por la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual, por su Reglamento y por la normatividad institucional vigente. Alberto Gabino Loaiza Freire CERTIFICACIÓN Certifico que el presente trabajo fue desarrollado por ALBERTO GABINO LOAIZA FREIRE, bajo mi supervisión. Ing. Fernando Flores DIRECTOR DE PROYECTO AGRADECIMIENTO A mi Esposa Daisy Elena por su ayuda y apoyo incondicional. Al Ing. Pablo Vega por su colaboración desinteresada para el desarrollo de este proyecto. Al Ing. Fernando Flores por su acertada guía durante la elaboración de este proyecto. A Grupo TVCable por el auspicio y el apoyo brindado en la realización de este proyecto. DEDICATORIA Se lo dedico muy especialmente al amor de mi vida, a la compañera de mi vida, a mi esposa Daisy Elena. Se lo dedico también a mi familia: a mi Madre que ha sido un ejemplo de vida, a mis hermanas Alex y Carla por el apoyo incondicional en todo momento, y a mi Padre por creer y confiar siempre en mí. -

The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television

UC Santa Barbara Global Societies Journal Title The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/13s698mx Journal Global Societies Journal, 1(1) Author Elouardaoui, Ouidyane Publication Date 2013 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television | 100 The Crisis of Contemporary Arab Television: Has the Move towards Transnationalism and Privatization in Arab Television Affected Democratization and Social Development in the Arab World? By: Ouidyane Elouardaoui ABSTRACT Arab media has experienced a radical shift starting in the 1990s with the emergence of a wide range of private satellite TV channels. These new TV channels, such as MBC (Middle East Broadcasting Center) and Aljazeera have rapidly become the leading Arab channels in the realms of entertainment and news broadcasting. These transnational channels are believed by many scholars to have challenged the traditional approach of their government–owned counterparts. Alternatively, other scholars argue that despite the easy flow of capital and images in present Arab television, having access to trustworthy information still poses a challenge due to the governments’ grip on the production and distribution of visual media. This paper brings together these contrasting perspectives, arguing that despite the unifying role of satellite Arab TV channels, in which national challenges are cast as common regional worries, democratization and social development have suffered. One primary factor is the presence of relationships forged between television broadcasters with influential government figures nationally and regionally within the Arab world. -

25C Strong Winds Befall 36Th St. Tree

\ * i. I I III- I •• I , 25C HCAG a SONS* 30OK DIAPER SPR1NGPORT, MICHIGAN 49284 The Lowell Olume 14. Issue 10 Serving Lowell Area Readers Since 1893 Wednesday, January 17, 1990 Along Main Street City Council accepts substation explanation. J-'l rr In a letter to the Lowell City Council, the Lowell Light * I. Proximity to existing overhead distribution lines. - 'T^T i i and Power Board stated that it reviewed and approved the * 2. Proximity to Bowes Street. v-sn - i.—^ yi K j •' * , jr*. t 1 l\ relocation of the Bowes Road substation without any inten- * 3. Undergmund electric circuits. f tional or malicious intent. 4. Overhead line maintenance. fc L wl i 'V^yv^ The Council received and reviewed the letter and accepted * 5. Vandalism. the explanation," Lowell City Manager Dave Pasquale said. To avoid similar problems in the future, the Lowell Light Under the initial survey reviewed by the council in January and Power Board said it is committed to improving communi- of 1989. it was determined by the Lowell Light and Power cations with the City Council, and furtherrecommended tha t ATTENTION! AREA RECYCLERS! engineer that the substation could not be located under the the City subject all future Light and Power construction sites power lines and would have to be moved back. to the same review process that it would apply to any other The rccyclc station in the FckxI City parking lot (1335 At the time. Williams and Works was instructed to re-survey construction in the City, including site plans, permits, and W. -

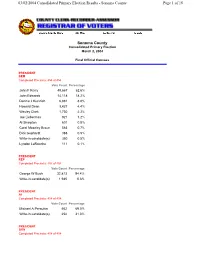

Consolidated Primary Election Results Summary

03/02/2004 Consolidated Primary Election Results - Sonoma County Page 1 of 18 Sonoma County Consolidated Primary Election March 2, 2004 Final Official Canvass PRESIDENT DEM Completed Precincts: 454 of 454 Vote Count Percentage John F Kerry 48,667 62.6% John Edwards 14,118 18.2% Dennis J Kucinich 6,881 8.8% Howard Dean 3,427 4.4% Wesley Clark 1,730 2.2% Joe Lieberman 921 1.2% Al Sharpton 601 0.8% Carol Moseley Braun 583 0.7% Dick Gephardt 388 0.5% Write-in candidate(s) 350 0.5% Lyndon LaRouche 111 0.1% PRESIDENT REP Completed Precincts: 454 of 454 Vote Count Percentage George W Bush 32,813 94.4% Write-in candidate(s) 1,945 5.6% PRESIDENT AI Completed Precincts: 454 of 454 Vote Count Percentage Michael A Peroutka 562 69.0% Write-in candidate(s) 252 31.0% PRESIDENT GRN Completed Precincts: 454 of 454 03/02/2004 Consolidated Primary Election Results - Sonoma County Page 2 of 18 Vote Count Percentage Peter Miguel Camejo 2,087 73.8% Lorna Salzman 307 10.9% Write-in candidate(s) 203 7.2% David Cobb 197 7.0% Kent Mesplay 34 1.2% PRESIDENT LIB Completed Precincts: 454 of 454 Vote Count Percentage Gary Nolan 330 54.0% Aaron Russo 141 23.1% Michael Badnarik 101 16.5% Write-in candidate(s) 39 6.4% PRESIDENT NAT Completed Precincts: 454 of 454 Vote Count Percentage Write-in candidate(s) 25 100.0% NO CANDIDATE HAS FILED 0 0.0% PRESIDENT PF Completed Precincts: 454 of 454 Vote Count Percentage Leonard Peltier 147 62.8% Walter F Brown 67 28.6% Write-in candidate(s) 20 8.5% PRESIDENT DEM DTS Completed Precincts: 454 of 454 Vote Count Percentage John F -

Ida Documentary Awards

IDA DOCUMENTARY international documentary AWARDS12 association 28th DEC 7.2012 DEC ANNUAL Guild Directors America of CONGRATULATIONS TO ALL THE NOMINEES OF THE 2012 IDA DOCUMENTARY AWARDS A&E INDIEFILMS IS PROUD TO SUPPORT THE INTERNATIONAL DOCUMENTARY ASSOCIATION. IDA DOCUMENTARY AWARDS12 sponsors LUMINARY SPONSORS GOLD SPONSORS SILVER SPONSORS 3 IDA DOCUMENTARY AWARDS12 28th Annual IDA Documentary Awards December 7, 2012 6:30 PM PRIVATE RECEPTION HONORING ARNOLD SHAPIRO Sponsored by A&E LOCATION: DGA Atrium Awards Ceremony HOST: Penn Jillette 8:00 PM AWARDS CEREMONY • Year In Review LOCATION: DGA Theater 1 • ABCNEWS VideoSource Award 9:30 PM • Best Limited Series Award AFTER PARTY • Pare Lorentz Award Sponsored by Canon LOCATION: DGA Grand Lobby • David L. Wolper Student Documentary Award • Creative Recognition Awards: Best Cinematography Best Editing Best Music Best Writing • Jacqueline Donnet Emerging Documentary Filmmaker Award • Pioneer Award • Best Continuing Series Award • HUMANITAS Documentary Award • Career Achievement Award • Best Short Award • Best Feature Award 5 CONGRATULATIONS! ABCNEWS VIDEOSOURCE FINALISTS AND THE NOMINEES & HONOREES OF THE 28TH ANNUAL IDA DOCUMENTARY AWARDS IN RECOGNITION OF YOUR EXTRAORDINARY WORK www.abcnewssource.com IDA DOCUMENTARY AWARDS12 nominees & honorees ABCNEWS VIDEOSOURCE BEST LIMITED SERIES AWARD NOMINEES AWARD NOMINEES BOOKER’S PLACE: A MISSISSIPPI STORY BOMB PATROL: AFGHANISTAN DIRECTOR: Raymond De Felitta EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS: Dan Cesareo, Doug DePriest, PRODUCER: David Zellerford Vince DiPersio, Laura Civiello, Tim Rummel EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS: Lynn Roer, Steven Beer SERIES PRODUCERS: Kathryn Gilbert, Joe Venafro, Keith Saunders Eyepatch Productions/Ogilvy, PRODUCERS/SHOOTERS: Joe Venafro, Christopher Whiteneck, Hangover Lounge, Tribeca Film David D’Angelo, Scott Stoneback Big Fish Entertainment for NBC/G4 Media, Inc. -

2017 Institutional Master Plan

2017 InstItutIonal Master Plan 2017 InstItutIonal Master Plan Table of Contents I. Introduction 3 II. Executive Summary 4 III. Academy of Art University Overview 10 Mission 10 Commitment to an Urban Campus 11 History of the Academy of Art University 11 IV. Academic Departments and Curricula 12 Online Students 12 Alignment of Degree Programs Online/Onsite 12 Online Course Approval 13 Accreditation 13 Academy Programs 14 Classic Automobile Collection 17 Academy of Art University Athletics 17 V. City and Neighborhood Benefits and Impacts 18 Benefits Overview 18 Security and Maintenance 20 Addressing Neighborhood Needs 20 Scholarships for San Francisco and Bay Area Residents 21 Active Engagement in Community Programs 21 Pro-Bono Design Work and Other Academy Civic Engagement 22 VI. Students, Faculty and Staff 31 Enrollment 31 Enrollment Trends 32 Diversity 34 Student Housing 34 Cost of Attendance & Financial Aid 35 Faculty and Staff 37 The Academy’s Equal Employment Policy 37 VII. Existing Facilities 38 Neighborhood Context and Land Use Requirements 38 Policy of Adaptive Re-Use 41 Campus Safety 41 VIII. Current and Future Needs 45 10-yr Plan: Consolidate and Centralize the Campus 45 Near Term Plan: Proposed Changes to the Academy Campus 46 Transportation: Changes and Improvements Affecting the Shuttle Program 50 Student Housing and Metering Relationship to Enrollment 52 IX. Environmental Impact Report and the Existing Sites Technical Memorandum 53 Historic Preservation 53 X. General Plan Consistency 54 San Francisco Priority Policies 54 Consistency of General Plan Elements 56 Relevant Area Plans 61 XI. Attachments 64 Attachment 1: Employers 64 Attachment 2: Neighborhood Context Groups 76 Attachment 3: Existing Institutional and Residential Sites 77 Attachment 4: Study Areas 78 Attachment 5: Shuttle Systems: Current and Proposed/Future Shuttle Map 79 2 2017 Institutional Master Plan VIII. -

Grizzly Si Plifies Complex Obstacles Gets More Time to Gather Facts

_ II~ range: TA 250 instructors help them- Volume 9 Number 10 Published in the interest of the personnel at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri Thursday, March 7, 1996 Home on the - ------------------ selves to a new shelter. See page 3A ----------------- -- BRAC on track Luncheon features Ann Crossley Q Maneuver Support struction facilities, NCO academy The Officers and Civilians Center transformation accommodations, range modifica- Women's Club luncheon fea- tions and housing conversions. turing Ann Crossley, author of proceeding smoothly "We're adequately funded for the 'Army Wives Handbook," the design of all projects and have is on March 21, 11:30 a.m., By Jacqueline Guthrie been approved for construction," not March 12 as previously pub- ESSAYONS Staff he added. Contractors will start lished. See complete story on breaking ground early next year. page lB. Fort Leonard Wood is well on "We also have a very solid start- its way to becoming the Maneuver up on the environmental impact Joint Endeavor troops Support Center as the Base Re- statement," Johnson said. This get tax extension alignment and Closure statement is part of the legal re- The Internal Revenue Ser- Commission transition office here quirements of the National vice has granted an automatic celebrate its one-year anniversary. Environmental Policy Act of 1969 extension to Dec. 15 to file The BRAC team has the job of that requires all federal agencies 1995 Federal Income Tax Re- moving of the Military Police and to complete one for activities that turns to soldiers serving in Chemical Schools from Fort could affect the environment. Operation Joint Endeavor on McClellan, Ala., to Fort Leonard Officials began preparing the in- or after March 15.