A Textual Analysis of the Closer and Saving Grace: Feminist and Genre Theory in 21St Century Television

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hampe, George 1-29

GEORGE HAMPE THEATRE Romeo and Juliet Romeo Huntington Theater, Dir. Peter DuBois Dead Metaphor (World Prem.) Dean Trusk A.C.T., Dir. Irene Lewis Arcadia Valentine (u/s) Yale Rep, Dir. James Bundy Regrets Caleb/Hanratty (u/s) Manhattan Theatre Club, Dir. Carolyn Cantor Another Day, Another Dream (World Prem.) Jack Pittsburgh Irish & Classical Theatre, Dir. Stephanie Riso Much Ado About Nothing Claudio Pittsburgh Shakespeare in the Parks Geography of a Horse Dreamer The Waiter Pittsburgh Irish & Classical Theatre YALE SCHOOL OF DRAMA Tis Pity She’s a Whore Soranzo Dir. Jess Rasmussen Tiny Neil Dir. Kevin Hourigan Mrs. Galveston Jim Dir. Rachel Carpman (Yale Cabaret) The Three Sisters Tusenbach Dir. Joan MacIntosh Clybourne Park Jim/Tom/Kenneth Dir. Joan MacIntosh Merchant of Venice Gratiano/Aragon Dir. Kevin Hourigan Othello Brabantio/Montano Dir. Beth Dinkova UBU ROI Company Dir. Christopher Bayes Measure for Measure Duke Ensemble TELEVISION AND FILM The Chaperone Supporting Lead Masterpiece/ Michael Engler Madam Secretary Co-Star CBS/ Rob Greenlea The Good Fight Co-Star CBS/ Michael Zinberg Unforgettable Co-Star CBS/ Matt Earl Beasley Blue Bloods Co-Star CBS/ Martha Mitchell One Tree Hill Co-Star WB/ Austin Nichols Wicked Attraction Guest Star The Discovery Channel TRAINING MFA - Yale School of Drama Ron Van Lieu, Evan Yionoulis, Robert Woodruff, Peter Francis James, Steven Skybell, James Bundy, Beth McGuire, Ron Carlos, Christopher Bayes, Glenn Allen, Anne Tofflemire, Rick Sordelet, Michael Rossmy, Jessica Wolf, Bill Connington. Stella Adler Studio of Acting: Antonio Merenda, Jon Korkes, Joanne Edelmann Upright Citizen’s Brigade (101, 201): Patrick Clair, Kevin Hines, Molly Thomas Special Skills: Improvisation, Ukulele, Guitar, Horseback Riding, Singing (Tenor/Baritone) MANAGER: Kate Moran / Untitled Ent. -

Latino Representation on Primetime Television in English and Spanish Media: a Framing Analysis

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Master's Theses Master's Theses and Graduate Research Spring 2017 Latino Representation On Primetime Television In English and Spanish Media: A Framing Analysis Gabriela Arellano San Jose State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses Recommended Citation Arellano, Gabriela, "Latino Representation On Primetime Television In English and Spanish Media: A Framing Analysis" (2017). Master's Theses. 4785. DOI: https://doi.org/10.31979/etd.2wvs-3sd3 https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/4785 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Master's Theses and Graduate Research at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Journalism and Mass Communications San José State University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science by Gabriela Arellano May 2017 © 2017 Gabriela Arellano ALL RIGHTS RESERVED The Designated Thesis Committee Approves the Thesis Titled LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS by Gabriela Arellano APPROVED FOR THE SCHOOL OF JOURNALISM AND MASS COMMUNICATIONS SAN JOSÉ STATE UNIVERSITY May 2017 Dr. Diana Stover School of Journalism and Mass Communications Dr. William Tillinghast School of Journalism and Mass Communications Professor John Delacruz School of Journalism and Mass Communications ABSTRACT LATINO REPRESENTATION ON PRIMETIME TELEVISION IN ENGLISH AND SPANISH MEDIA: A FRAMING ANALYSIS by Gabriela Arellano The purpose of this study was to provide updated data on the Latino portrayals on primetime English and Spanish-language television. -

Games+Production.Pdf

This may be the author’s version of a work that was submitted/accepted for publication in the following source: Banks, John& Cunningham, Stuart (2016) Games production in Australia: Adapting to precariousness. In Curtin, M & Sanson, K (Eds.) Precarious creativity: Global media, local labor. University of California Press, United States of America, pp. 186-199. This file was downloaded from: https://eprints.qut.edu.au/87501/ c c 2016 by The Regents of the University of California This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC-BY license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses. License: Creative Commons: Attribution 4.0 Notice: Please note that this document may not be the Version of Record (i.e. published version) of the work. Author manuscript versions (as Sub- mitted for peer review or as Accepted for publication after peer review) can be identified by an absence of publisher branding and/or typeset appear- ance. If there is any doubt, please refer to the published source. http:// www.ucpress.edu/ book.php?isbn=9780520290853 CURTIN & SANSON | PRECARIOUS CREATIVITY Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserving and rein- vigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org Precarious Creativity Precarious Creativity Global Media, Local Labor Edited by Michael Curtin and Kevin Sanson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advanc- ing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. -

The Madison Square Garden Company Announces Bob Saget

January 24, 2017 The Madison Square Garden Company Announces Bob Saget Has Been Added to the All- Star Lineup of Garden of Laughs, Presented by Delta Air Lines, to Benefit The Garden of Dreams Foundation SAGET JOINS LESLIE JONES, SEBASTIAN MANISCALCO, TRACY MORGAN, JOHN OLIVER AND CHRIS ROCK FOR A NIGHT OF STAND-UP COMEDY HOSTED BY STEVE SCHIRRIPA AT THE THEATER AT MADISON SQUARE GARDEN ON TUESDAY, MARCH 28 AT 8:00 PM Already Confirmed Celebrity Appearances By Adam Graves, Matt Lauer, Spike Lee, Darryl "DMC" McDaniels, Mark Messier, John Starks and Justin Tuck With Additional Celebrity Presenters To Be Announced Garden_of_Laughs Logo.jpg NEW YORK, Jan. 24, 2017 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- The Madison Square Garden Company (NYSE:MSG) and The Garden of Dreams Foundation is pleased to announce that Grammy Award-nominated comedian and the star of two of the most successful network TV shows ever produced, Bob Saget, has joined the Garden of Laughs presented by Delta Air Lines. The bi-annual all-star comedy benefit will take place at The Theater at Madison Square Garden on Tuesday, March 28, 2017 at 8:00 p.m., with all net proceeds going directly to Garden of Dreams. As previously announced, Jerry Seinfeld will now be unable to attend the Garden of Laughs fundraiser as was previously scheduled. Instead, Seinfeld announced that he would donate the proceeds from an upcoming 2017 show at the Beacon Theatre to the Foundation. Saget is perhaps best known for his work as the star of two of the most family-friendly shows network TV has ever produced ("Full House" and "Americas Funniest Home Videos") but he's also been an out-of- his-mind standup comedian for over thirty years. -

An Open Letter to President Biden and Vice President Harris

An Open Letter to President Biden and Vice President Harris Dear President Biden and Vice President Harris, We, the undersigned, are writing to urge your administration to reconsider the United States Army Corps of Engineers’ use of Nationwide Permit 12 (NWP12) to construct large fossil fuel pipelines. In Memphis, Tennessee, this “fast-tracked” permitting process has given the green light to the Byhalia pipeline, despite the process wholly ignoring significant environmental justice issues and the threat the project potentially poses to a local aquifer which provides drinking water to one million people. The pipeline route cuts through a resilient, low-wealth Black community, which has already been burdened by seventeen toxic release inventory facilities. The community suffers cancer rates four times higher than the national average. Subjecting this Black community to the possible health effects of more environmental degradation is wrong. Because your administration has prioritized the creation of environmental justice, we knew knowledge of this project would resonate with you. The pipeline would also cross through a municipal well field that provides the communities drinking water. To add insult to injury, this area poses the highest seismic hazard in the Southeastern United States. The Corps purports to have satisfied all public participation obligations for use of NWP 12 on the Byhalia pipeline in 2016 – years before the pipeline was proposed. We must provide forums where communities in the path of industrial projects across the country can be heard. Neighborhoods like Boxtown and Westwood in Memphis have a right to participate in the creation of their own destinies and should never be ignored. -

2010 16Th Annual SAG AWARDS

CATEGORIA CINEMA Melhor ator JEFF BRIDGES / Bad Blake - "CRAZY HEART" (Fox Searchlight Pictures) GEORGE CLOONEY / Ryan Bingham - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) COLIN FIRTH / George Falconer - "A SINGLE MAN" (The Weinstein Company) MORGAN FREEMAN / Nelson Mandela - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) JEREMY RENNER / Staff Sgt. William James - "THE HURT LOCKER" (Summit Entertainment) Melhor atriz SANDRA BULLOCK / Leigh Anne Tuohy - "THE BLIND SIDE" (Warner Bros. Pictures) HELEN MIRREN / Sofya - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny - "AN EDUCATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) GABOUREY SIDIBE / Precious - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) MERYL STREEP / Julia Child - "JULIE & JULIA" (Columbia Pictures) Melhor ator coadjuvante MATT DAMON / Francois Pienaar - "INVICTUS" (Warner Bros. Pictures) WOODY HARRELSON / Captain Tony Stone - "THE MESSENGER" (Oscilloscope Laboratories) CHRISTOPHER PLUMMER / Tolstoy - "THE LAST STATION" (Sony Pictures Classics) STANLEY TUCCI / George Harvey – “UM OLHAR NO PARAÍSO” ("THE LOVELY BONES") (Paramount Pictures) CHRISTOPH WALTZ / Col. Hans Landa – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) Melhor atriz coadjuvante PENÉLOPE CRUZ / Carla - "NINE" (The Weinstein Company) VERA FARMIGA / Alex Goran - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) ANNA KENDRICK / Natalie Keener - "UP IN THE AIR" (Paramount Pictures) DIANE KRUGER / Bridget Von Hammersmark – “BASTARDOS INGLÓRIOS” ("INGLOURIOUS BASTERDS") (The Weinstein Company/Universal Pictures) MO’NIQUE / Mary - "PRECIOUS: BASED ON THE NOVEL ‘PUSH’ BY SAPPHIRE" (Lionsgate) Melhor elenco AN EDUCATION (Sony Pictures Classics) DOMINIC COOPER / Danny ALFRED MOLINA / Jack CAREY MULLIGAN / Jenny ROSAMUND PIKE / Helen PETER SARSGAARD / David EMMA THOMPSON / Headmistress OLIVIA WILLIAMS / Miss Stubbs THE HURT LOCKER (Summit Entertainment) CHRISTIAN CAMARGO / Col. John Cambridge BRIAN GERAGHTY / Specialist Owen Eldridge EVANGELINE LILLY / Connie James ANTHONY MACKIE / Sgt. -

ALEX NEPOMNIASCHY, ASC Director of Photography Alexnepomniaschy.Com

ALEX NEPOMNIASCHY, ASC Director of Photography alexnepomniaschy.com PROJECTS Partial List DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS THE MARVELOUS MRS. MAISEL Daniel Palladino AMAZON STUDIOS / Nick Thomason Season 4 Amy Sherman-Palladino MIXTAPE Ti West ANNAPURNA PICTURES Series NETFLIX / Chip Vucelich, Josh Safran L.A.’S FINEST Eagle Egilsson SONY PICTURES TELEVISION Series Mark Tonderai Scott White, Jerry Bruckheimer WISDOM OF THE CROWD Adam Davidson CBS Series Jon Amiel Ted Humphrey, Vahan Moosekian Milan Cheylov Adam Davidson GILMORE GIRLS: A YEAR IN THE LIFE Amy Sherman- WARNER BROS. TV / NETFLIX Mini-series Palladino Daniel Palladino Daniel Palladino Amy Sherman-Palladino THE AMERICANS Thomas Schlamme DREAMWORKS / FX Season 4 Chris Long Mary Rae Thewlis, Chris Long Daniel Sackheim Joe Weisberg, Joel Fields THE MENTALIST Chris Long WARNER BROS. / CBS Season 7 Simon Baker Matthew Carlisle, Bruno Heller Nina Lopez-Corrado Chris Long STANDING UP D.J. Caruso ALDAMISA Janet Wattles, Jim Brubaker Ken Aguado, John McAdams BLUE BLOODS David Barrett CBS Seasons 4 & 5 John Behring Jane Raab, Kevin Wade Alex Chapple Eric Laneuville I AM NUMBER FOUR D.J. Caruso DREAMWORKS Add’l Photography Sue McNamara, Michael Bay BIG LOVE Daniel Attias HBO Season 4 David Petrarca Bernie Caulfield THE EDUCATION OF CHARLIE BANKS Fred Durst Marisa Polvino, Declan Baldwin TAKE THE LEAD Liz Friedlander NEW LINE Diane Nabatoff, Michelle Grace CRIMINAL MINDS Pilot Richard Shepherd CBS / Peter McIntosh NARC Joe Carnahan PARAMOUNT PICTURES Nomination, Best Cinematography – Ind. Spirit -

COLEMAN, ROSALYN 2020 Resume

ROSALYNFilm COLEMAN THE IMMORTAL JELLYFISH Dusty Bias MISS VIRGINIA R.J. Daniel Hanna EVOLUTION OF A CRIMINAL Darious Clarke Monroe/Spike Lee Producer IT’S KIND OF A FUNNY STORY Ryan Fleck & Ana Bolden TWELVE Joel Schumacher FRANKIE & ALICE (w/Halle Berry) Geoffrey Sax BROOKLYN’S FINEST Antwoine Fuqua/Warner Bros. BROWN SUGAR (w/Taye Diggs) Rick Famuyiwa/20th Century Fox VANILLA SKY (w/Tom Cruise) Cameron Crowe/ Artisan OUR SONG (w/Kerry Washington) Jim McKay/Stepping Pictures MUSIC OF THE HEART (w/Meryl Streep) Wes Craven/Miramax MIXING NIA Alison Swan/Independent PERSONALS Mike Sargent/Independent Television JESSICA JONES Netflix BULL CBS MADAM SECRETARY CBS BLUE BLOODS CBS ELEMENTARY CBS WHITE COLLAR USA SPRING/FALL (Pilot) HBO Pilot NURSE JACKIE Showtime MERCY (Pilot) NBC NEW AMSTERDAM FOX KIDNAPPED (recurring) NBC LAW & ORDER SVU & CI NBC/Jim McKay/Michael Zinberg DEADLINE NBC OZ (recurring) HBO/Alex Zakrzewski D.C. (recurring) WB/Dick Wolf producer THE PIANO LESSON Lloyd Richards/Hallmark Hall of Fame THE DITCHDIGGER’S DAUGHTERS Johnny Jensen/Family Channel Broadway TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD Bartlett Shear TRAVESTIES us Patrick Marber/Roundabout Theatre Co. THE MOUNTAINTOP us Kenny Leon RADIO GOLF us Kenny Leon SEVEN GUITARS Lloyd Richards THE PIANO LESSON Lloyd Richards MULE BONE Michael Shultz Off Broadway NATIVE SON Acting Company/Yale Rep/ Seret Scott SCHOOL GIRLS OR THE AFRICAN MEAN GIRLS PLAY us MCC /Rebecca Taichman PIPELINE us Lincoln Center Theatre/Lileana Blain-Cruz BREAKFAST WITH MUGABE Signature Theater/David Shookov ZOOMAN & THE SIGN Signature Theatre/Steven Henderson WAR Rattlestick Theatre/Anders Cato THE SIN EATER 59 E. -

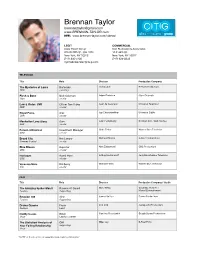

Brennan Taylor [email protected] REEL

Brennan Taylor [email protected] www.BRENNAN-TAYLOR.com REEL www.brennan-taylor.com/videos/ LEGIT COMMERCIAL Clear Talent Group Don Buchwald & Associates 325 W 38th St., Ste 1203 10 E 44th St. New York, NY 10018 New York, NY 10017 (212) 840-4100 (212) 634-8348 [email protected] TELEVISION Title Role Director Production Company The Mysteries of Laura Bartender Randy Zisk Berlanti Productions NBC recurring Flesh & Bone Nick Coleman Adam Davidson Starz Originals Starz co-star Law & Order: SVU Officer Tom Haley Jean de Segonzac Universal Television NBC co-star Royal Pains Alex Jay Chandrasekhar Universal Cable USA co-star Manhattan Love Story Sam John Fortenberry Brillstein Ent. / ABC Studios ABC co-star Person of Interest Investment Manager Chris Fisher Warner Bros Television CBS co-star Broad City Hot Lawyer Michael Blieden 3 Arts Entertainment Comedy Central co-star Blue Bloods Reporter Alex Zakrzewski CBS Productions CBS co-star Hostages Agent Horn Jeffrey Nachmanoff Jerry Bruckheimer Television CBS co-star Veronica Mars RA Gerry Michael Fields Warner Bros Television CW co-star FILM Title Role Director Production Company / Studio The Amazing Spider-Man II Ravencroft Guard Marc Webb Columbia Pictures / Feature Supporting Marvel Entertainment Reunion 108 Allen James Suttles Carms Productions Feature Supporting Drama Queens Frank Levi Lieb Juxtaposed Productions Feature Lead Daddy Issues Dillon Carolina Roca-Smith Grizzly Bunny Productions Short Lead & co-writer The Statistical Analysis of Cliff Miles Jay B-Reel Films Your Failing Relationship Supporting Short *A PDF of this is online at: www.brennan-taylor.com/resume/. -

Speed Kills / Hannibal Production in Association with Saban Films, the Pimienta Film Company and Blue Rider Pictures

HANNIBAL CLASSICS PRESENTS A SPEED KILLS / HANNIBAL PRODUCTION IN ASSOCIATION WITH SABAN FILMS, THE PIMIENTA FILM COMPANY AND BLUE RIDER PICTURES JOHN TRAVOLTA SPEED KILLS KATHERYN WINNICK JENNIFER ESPOSITO MICHAEL WESTON JORDI MOLLA AMAURY NOLASCO MATTHEW MODINE With James Remar And Kellan Lutz Directed by Jodi Scurfield Story by Paul Castro and David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Screenplay by David Aaron Cohen & John Luessenhop Based upon the book “Speed Kills” by Arthur J. Harris Produced by RICHARD RIONDA DEL CASTRO, pga LUILLO RUIZ OSCAR GENERALE Executive Producers PATRICIA EBERLE RENE BESSON CAM CANNON MOSHE DIAMANT LUIS A. REIFKOHL WALTER JOSTEN ALASTAIR BURLINGHAM CHARLIE DOMBECK WAYNE MARC GODFREY ROBERT JONES ANSON DOWNES LINDA FAVILA LINDSEY ROTH FAROUK HADEF JOE LEMMON MARTIN J. BARAB WILLIAM V. BROMILEY JR NESS SABAN SHANAN BECKER JAMAL SANNAN VLADIMIRE FERNANDES CLAITON FERNANDES EUZEBIO MUNHOZ JR. BALAN MELARKODE RANDALL EMMETT GEORGE FURLA GRACE COLLINS GUY GRIFFITHE ROBERT A. FERRETTI SILVIO SARDI “SPEED KILLS” SYNOPSIS When he is forced to suddenly retire from the construction business in the early 1960s, Ben Aronoff immediately leaves the harsh winters of New Jersey behind and settles his family in sunny Miami Beach, Florida. Once there, he falls in love with the intense sport of off-shore powerboat racing. He not only races boats and wins multiple championship, he builds the boats and sells them to high-powered clientele. But his long-established mob ties catch up with him when Meyer Lansky forces him to build boats for his drug-running operations. Ben lives a double life, rubbing shoulders with kings and politicians while at the same time laundering money for the mob through his legitimate business. -

Weather Has the Bill Has Matter

T H U R S D A Y 161st YEAR • NO. 227 JANUARY 21, 2016 CLEVELAND, TN 16 PAGES • 50¢ A year of project completions ‘State of the City’ eyes present, future By JOYANNA LOVE spur even more economic growth a step closer toward the Spring Banner Senior Staff Writer FIRST OF 2 PARTS along the APD 40 corridor,” Rowland Branch Industrial Park becoming a said. reality. Celebrating the completion of some today. The City Council recently thanked “A conceptual master plan was long-term projects for the city was a He said the successes of the past state Rep. Kevin Brooks for his work revealed last summer, prepared by highlight of Cleveland Mayor Tom year were a result of hard work by city promoting the need for the project on TVA and the Bradley/Cleveland Rowland’s State of the City address. staff and the Cleveland City Council. the state level by asking that the Industrial Development Board,” “Our city achieved several long- The mayor said, “Exit 20 is one of Legislature name the interchange for Rowland said. term goals the past year, making 2015 our most visible missions accom- him. The interchange being constructed an exciting time,” Rowland said. “But plished in 2015. Our thanks go to the “The wider turn spaces will benefit to give access to the new industrial just as exciting, Cleveland is setting Tennessee Department of trucks serving our existing park has been named for Rowland. new goals and continues to move for- Transportation and its contractors for Cleveland/Bradley County Industrial “I was proud and humbled when I ward, looking to the future for growth a dramatic overhaul of this important Park and the future Spring Branch learned this year the new access was and development.” interchange. -

The Influence of Media on Views of Gender

Article 7 Gendered Media: The Influence of Media on Views of Gender Julia T. Wood Department of Communication, University of North times more often than ones about women (“Study Re- Carolina at Chapel Hill ports Sex Bias,” 1989), media misrepresent actual pro- portions of men and women in the population. This constant distortion tempts us to believe that there really THEMES IN MEDIA are more men than women and, further, that men are the cultural standard. Of the many influences on how we view men and women, media are the most pervasive and one of the most powerful. Woven throughout our daily lives, media insinuate their messages into our consciousness at every MEDIA’S MISREPRESENTATION OF turn. All forms of media communicate images of the sexes, many of which perpetuate unrealistic, stereotypi- AMERICAN LIFE cal, and limiting perceptions. Three themes describe how media represent gender. First, women are underrepre- The media present a distorted version of cultural life sented, which falsely implies that men are the cultural in our country. According to media portrayals: standard and women are unimportant or invisible. Sec- ond, men and women are portrayed in stereotypical White males make up two-thirds of the popula- ways that reflect and sustain socially endorsed views of tion. The women are less in number, perhaps be- cause fewer than 10% live beyond 35. Those who gender. Third, depictions of relationships between men do, like their younger and male counterparts, are and women emphasize traditional roles and normalize nearly all white and heterosexual. In addition to violence against women. We will consider each of these being young, the majority of women are beauti- themes in this section.