Voting" À La Carte": Electoral Support for the Radical Right in the 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bulgaria – the Difficult “Return to Europe”

European Democracy in Action BULGARIA – THE DIFFICULT “RETURN TO EUROPE” TAMARA BUSCHEK Against the background of the EU accession of Bulgaria on 1st January 2007 and the first Bulgarian elections for the European Parliament on 20th May 2007, Tamara Buschek takes a closer look at Bulgaria’s uneven political and economic transition – at its difficult “return to Europe”. Graduated from Graz University (Austria) in 2003 with a Masters in Law [magistra juris] after finishing her studies in European and international law. After gaining a grant from the Chamber of Commerce in 2000 to complete an internship at the Austrian Embassy in London, she carried out research for her dissertation in criminal law – “The Prevention of Sexual Child Abuse – Austria/Great Britain” - in 2001 at the London School of Economics. She studied European and administrative law in Paris from 2001 to 2002 as part of an Erasmus year. She is quadrilingual (German, Bulgarian, English and French). « BULGARIA – THE DIFFICULT RETURN TO EUROPE » MAY 2007 Table of Contents Introduction P. 1 2.3 The current governmental coalition, 2005-2007 and the P. 21 presidential election in 2006 I – Background Information P. 3 III - The first European Parliament elections, 20 May 2007 P. 25 1.1 Hopes and Fears P. 3 Conclusion P. 30 1.2 Ethnic Minorities P. 5 1.3 Economic Facts P. 7 Annex P. 32 II – Political Situation- a difficult path towards stability P. 9 Annex 1: Key facts P. 32 2.1 The transition from 1989 till 2001 P. 9 Annex 2: Economic Profile P. 33 2.1.1 The legislative elections of 1990 and the first P. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Is left/right still the ‘super glue’? The role of left/right ideology and issues in electoral politics in Western and East Central Europe Walczak, A. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Walczak, A. (2012). Is left/right still the ‘super glue’? The role of left/right ideology and issues in electoral politics in Western and East Central Europe. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:28 Sep 2021 Appendices 113 .3 .3 R² R² .27 .27 .37 .37 .33 .35 .35 .33 .35 .35 .29 .29 n .3 .83 .32 .59 .46 .55 .45 .47 .26 EU 1.04) (-.12, (.14, .5) .5) (.14, (.1, .42) (.41, .76) (.23, .87) (.19, .72) (.21, .73) (.05, .55) (.48, 1.19) Integratio .2 .3 .86 .86 .27 .27 .12 .12 .22 .22 .27 .27 .34 .34 -.06 (.52, 1.2) (.13, .41) (.06, .34) (.06, .53) (.09, .54) (.15, .39) (-.51, .39) (-.09, .77) (-.13, .37) Decrease of Immigration Immigration age regression forvoters .2 of .58 .28 .23 .35 .24 .16 .48 .002 .002 (.2, .96) (.15, .8) (.04, .36) (.07, .49) (.04, .29) (-.41, .41) (-.08, .55) (-.19, .89) (-.46, .94) Immigrants Immigrants ountry were regressed on voters’ voters’ regressed on were ountry s, religion, education and age. -

List of Political Parties

Manifesto Project Dataset Political Parties in the Manifesto Project Dataset [email protected] Website: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/ Version 2015a from May 22, 2015 Manifesto Project Dataset Political Parties in the Manifesto Project Dataset Version 2015a 1 Coverage of the Dataset including Party Splits and Merges The following list documents the parties that were coded at a specific election. The list includes the party’s or alliance’s name in the original language and in English, the party/alliance abbreviation as well as the corresponding party identification number. In case of an alliance, it also documents the member parties. Within the list of alliance members, parties are represented only by their id and abbreviation if they are also part of the general party list by themselves. If the composition of an alliance changed between different elections, this change is covered as well. Furthermore, the list records renames of parties and alliances. It shows whether a party was a split from another party or a merger of a number of other parties and indicates the name (and if existing the id) of this split or merger parties. In the past there have been a few cases where an alliance manifesto was coded instead of a party manifesto but without assigning the alliance a new party id. Instead, the alliance manifesto appeared under the party id of the main party within that alliance. In such cases the list displays the information for which election an alliance manifesto was coded as well as the name and members of this alliance. 1.1 Albania ID Covering Abbrev Parties No. -

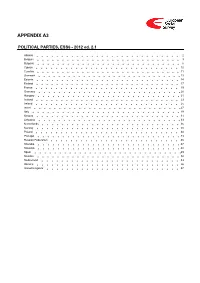

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

The Salience of European Integration to Party Competition: Western And

EEPXXX10.1177/0888325414567128East European Politics and SocietiesWhitefield and Rohrschneider / Salience of European Integration 567128research-article2015 East European Politics and Societies and Cultures Volume XX Number X Month 201X 1 –28 © 2015 SAGE Publications The Salience of European 10.1177/0888325414567128 http://eeps.sagepub.com hosted at Integration to Party http://online.sagepub.com Competition: Western and Eastern Europe Compared Stephen Whitefield Department of Politics and International Relations and Pembroke College, Oxford University Robert Rohrschneider Department of Political Science, The University of Kansas This article seeks to contribute to the burgeoning literature on how parties assign sali- ence to their issue stances. With regard to European integration, recent research has pointed not only to growing public Euro-scepticism but also to an increase in the importance that the public assigns to European issues. But are parties matching this shift with appropriate salience shifts of their own? The existing literature points to important constraints on parties achieving such salience representation that arise from the nature of inherited issue ownership and the nature of political cleavages. There are also reasons to expect important differences between Western European and Central European parties in the extent to which such constraints apply. We investigate these issues using data from expert surveys conducted in twenty-four European countries at two time points, 2007–2008 and 2013, that provide measures of the salience of European integration to parties along with other indicators that are used as predictors of salience. The results do not suggest that CEE parties assign salience in ways that differ substantially from their counterparts in Western Europe. -

The Party System in Bulgaria

ANALYSE DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN RIGHTS The second party system after 1989 (2001-2009) turns out THE PARTY SYSTEM to have been subjected to new turmoil after the Nation- IN BULGARIA al Assembly elections in 2009. 2009-2019 In 2009, GERB took over the government of the country on their own, and their leader Bor- isov was elected prime minister. Prof. Georgi Karasimeonov October 2019 Political parties are a key factor in the consolidation of the democratic political system. FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG – THE PARTY SYSTEM IN BULGARIA DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN RIGHTS THE PARTY SYSTEM IN BULGARIA 2009-2019 CONTENTS Contents 1. INTRODUCTION 2 2. THE ASSERTION OF GERB AS A PARTY OF POWER AND THE COLLAPSE OF THE COALITION OF BSP AND MRF 3 3. THE GOVERNMENT OF THE „BROAD SPECTRUM (MULTI-PARTY) COALITION“ AND THE IMPLICATIONS FOR THE PARTY SYSTEM (2014-2017) 9 4. POLITICAL PARTIES IN THE CONTEXT OF SEMI-CONSOLIDATED DEMOCRACY 13 5. CONCLUSION 15 1 FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG – THE PARTY SYSTEM IN BULGARIA 1 INTRODUCTION The second party system after 1989 (2001-2009) was sub- which have become part of European party families. In a ject to new changes after the elections for the National series of reports of the European Union, following the ac- Assembly in 2009. Its lability and ongoing transformation, cession of Bulgaria, harsh criticism has been levied, mainly and a growing crisis of trust among the citizens regarding against unsubjugated corruption and the ineffective judi- the parties, was evident. Apart from objective reasons con- ciary, which undermines not only the confidence of citi- nected with the legacy of the transition from the totalitar- zens in political institutions, but also hinders the effective ian socialist system to democracy and a market economy, use of EU funds in the interest of the socio-economic de- key causes of the crisis of trust in political parties were velopment of the country. -

Bulgaria – 1991 Parliamentary Elections

Bulgaria – 1991 Parliamentary elections CONST constituency 1 Blagoevgrad 2 Burgas 3 Varna 4 Veliko Turnovo 5 Vidin 6 Vratsa 7 Grabrovo 8 Dobrych 9 Kurdzhali 10 Kyustendil 11 Lovech 12 Montana 13 Pazardzhik 14 Pernik 15 Pleven 16 Plovdiv grad 17 Plovdivokrug 18 Razgrad 19 Ruse 20 Silistra 21 Sliven 22 Smolyan 23 Sofia 1 24 Sofia 2 25 Sofia 3 26 Sofia okrug 27 Stara Zagora 28 Turgovishche 29 Khaskovo 30 Shumen 31 Yambol PARTY nominating party 0 Independents 1 BBB - Bulgarian Business Block (Bulgarski Biznes Blok) 2 BBP - Bulgarian Business Party (Bulgarska biznes partiya) 3 BDP - Bulgarian Democratic Party (Bulgarska democraticheska partiya) 4 BDPESShch - Bulgarian Democratic Party for European and World States (Bulgarska demokraticheska partiya za evropeiski e svetovni shchati) 5 BKP - Bulgarian Communist Party (Bulgarska komunisticheska partiya) 6 BKP(m) - Bulgarian Communist Party - Marxist (Bulgarska komunisticheska partiya - marksisti) 7 BNDP Bulgarian National Democratic Party (Bulgarska natsionalna demokratichna partiya) 8 BNRP - Bulgarian National Radical Party (Bulgarska natsionalna radikalna partiya) 9 BNS - Coalition of the Bulgarian National Union - Bulgarian Fatherland Party and New Democracy Bulgarian National Union (Koalitsiya Bulgarski natisionalen suyuz - Bulgarska otechestvena partiya i Bulgarski natisionalen suyuz 'Nova Demokratsiya') 10 BPSDP - Bulgarian Workers' Social-Democratic Party (Bulgarska rabotnicheska sotsialdemokraticheska partiya) 11 BRMP Bulgarian Revolutionary Party of Youth - Varna (Bulgarska revolyutsionna -

Poldem – Protest Dataset 30 European Countries

PolDem – Protest Dataset 30 European countries - Version 1 - poldem-protest_30 Please cite as: Kriesi, Hanspeter, Wüest, Bruno, Lorenzini, Jasmine, Makarov, Peter, Enggist, Matthias, Rothenhäusler, Klaus, Kurer, Thomas, Häusermann, Silja, Patrice Wangen, Altiparmakis, Argyrios, Borbáth, Endre, Bremer, Björn, Gessler, Theresa, Hunger, Sophia, Hutter, Swen, Schulte-Cloos, Julia, and Wang, Chendi. 2020. PolDem-Protest Dataset 30 European Countries, Version 1. Short version for in-text citations & references: Kriesi, Hanspeter et al. 2020. PolDem-Protest Dataset 30 European Countries, Version 1. www.poldem.eu 1 Overview This document contains (1) information on the variables included in the protest event data compiled by the POLCON and Years-of-Turmoil research teams. The data collection relies on a semi- automated coding of newswire reports and covers 30 European countries and the time period from 2000 until 2015. The dataset is currently updated. (2) A detailed documentation of the data collection process (p. 12ff.) 2 Commented list of indicators Files: PEA30sixteen_Events_12042018.dta and PEA30sixteen_Events_12042018.csv N observations: 30,852 N variables: 53 Variable name Values Description id_doc 1…18222 document identifier (unambiguously describes a single document) id_coder 1…34 coder identifier (anonymized) event identifier (unambiguously describes one protest event, i.e. a unique combination of date, id_event 1…30852 action and location) entry_time "2016-05-03 19:59:46" … date and time of event annotation 1 = "austria" doc_country -

National Influences on Volt's First Election Campaign

Same same but different: National influences on Volt’s first election campaign Master Thesis In the field of European Union Studies For obtaining the academic degree of Master of Arts European Union Studies Submitted to the Faculty of Cultural and Social Sciences of the Paris-Lodron-University Salzburg And For obtaining the academic degree of Magister of European Studies with a Focus on European Law Submitted to the Faculty of Law of the Palacký University Olomouc Submitted by Johanna Klein, B.A. Matriculation Number: 11730677 Supervisors: Assoz.-Prof. Dr. Eric Miklin Department: Political Sciences / Centre of European Union Studies JUDr. Mag. iur. Michal Malacka, Ph.D., MBA Department: International and European Law Salzburg, Olomouc, July 2020 Acknowledgements Many thanks to all the members of Volt who were indirectly and directly involved in this project. A big thank you is directed to my supervisor Eric Miklin, who always actively supported me, no matter if I was in the Czech Republic, Belgium, Germany or Austria. Moreover, I would also like to thank my Co-Supervisor Michal Malacka. Thank you to my professors from the SCEUS and the Palacký University – you have broadened my horizon of knowledge. Special thanks to Miriam, you are the compass of the SCEUS. Danke an meine Lieben: Die, die mich auf die Idee gebracht haben dieses Studium zu beginnen und die, die mich auf meinem Weg begleiten. Danke fürs Zuhören, Diskutieren, gemeinsame Lernen. Danke an Lotti, besonders für die gemeinsamen Vormittage daheim. Danke an Papa für deine stetige und prägende Unterstützung, sowohl in akademischer als auch in ideeller Hinsicht. -

List of Political Parties

Manifesto Project Dataset List of Political Parties [email protected] Website: https://manifesto-project.wzb.eu/ Version 2017a from July 27, 2017 Manifesto Project Dataset - List of Political Parties Version 2017a 1 Coverage of the Dataset including Party Splits and Merges The following list documents the parties that were coded at a specific election. The list includes the name of the party or alliance in the original language and in English, the party/alliance abbreviation as well as the corresponding party identification number. In the case of an alliance, it also documents the member parties it comprises. Within the list of alliance members, parties are represented only by their id and abbreviation if they are also part of the general party list. If the composition of an alliance has changed between elections this change is reported as well. Furthermore, the list records renames of parties and alliances. It shows whether a party has split from another party or a number of parties has merged and indicates the name (and if existing the id) of this split or merger parties. In the past there have been a few cases where an alliance manifesto was coded instead of a party manifesto but without assigning the alliance a new party id. Instead, the alliance manifesto appeared under the party id of the main party within that alliance. In such cases the list displays the information for which election an alliance manifesto was coded as well as the name and members of this alliance. 2 Albania ID Covering Abbrev Parties No. Elections -

Republic of Bulgaria

Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 4 April 2021 ODIHR NEEDS ASSESSMENT MISSION REPORT 14-18 December 2020 Warsaw 28 January 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 1 II. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 1 III. FINDINGS ................................................................................................................................... 3 A. BACKGROUND AND POLITICAL CONTEXT .................................................................................. 3 B. LEGAL FRAMEWORK AND ELECTORAL SYSTEM ........................................................................ 4 C. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION ...................................................................................................... 5 D. VOTING TECHNOLOGIES ............................................................................................................. 6 E. VOTER REGISTRATION ................................................................................................................ 7 F. CANDIDATE AND PARTY REGISTRATION .................................................................................... 7 G. ELECTION CAMPAIGN ................................................................................................................. 8 H. CAMPAIGN FINANCE ..................................................................................................................