Glasgow Cathedral Statement of Significance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talking Gothic! What Do We Mean by Gothic Architecture and How Can We Identify It?

Talking Gothic! What do we mean by Gothic architecture and how can we identify it? ‘Gothic’ is the name we give to a style of architecture from the Middle Ages. It is usually thought to have begun near Paris in the middle of the 1100s and, from there, it spread throughout Europe and continued into the 16th century. There are many marvellous examples of Gothic buildings throughout Scotland: from Elgin Cathedral in Moray, through amazing buildings like Glasgow Cathedral, Paisley Abbey and Edinburgh St Giles, down to Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders. All of these, and more, are well worth a visit! Gothic architecture developed from an earlier style we call Romanesque. Buildings made in the Romanesque style often have rounded arches on their (usually comparatively small) windows and doors, thick columns and walls, lots of ornamental patterns, and shorter structures than the buildings which came later. Dunfermline Abbey is a great example of a Romanesque building in Scotland. The people who paid for the earliest Gothic buildings expressed a wish to transport worshippers to a kind of Heaven on Earth by building higher and brighter churches. What emerged is what we now describe as Gothic. Fashions changed throughout the time that Gothic was the predominant style, and it also varied from place to place. However, the Classical revival made popular as part of the Italian Renaissance largely replaced the Gothic style, and it wasn’t fashionable again until the 19th century. During the Romantic Movement Medieval literature, arts and crafts enjoyed renewed popularity. As a result, Glasgow Cathedral was begun in the Gothic elements can be seen today in the churches, public buildings, and late 12th century and was at the hub of the Medieval city. -

Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained a Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D

Welcome to OUR 4th VIRTUAL GSP class. Church Building Terms What Do Narthex and Nave Mean? Our Church Building Terms Explained A Virtual Class Prepared by Charles E.DICKSON,Ph.D. Lord Jesus Christ, may our church be a temple of your presence and a house of prayer. Be always near us when we seek you in this place. Draw us to you, when we come alone and when we come with others, to find comfort and wisdom, to be supported and strengthened, to rejoice and give thanks. May it be here, Lord Christ, that we are made one with you and with one another, so that our lives are sustained and sanctified for your service. Amen. HISTORY OF CHURCH BUILDINGS The Bible's authors never thought of the church as a building. To early Christians the word “church” referred to the act of assembling together rather than to the building itself. As long as the Roman government did not did not recognize and protect Christian places of worship, Christians of the first centuries met in Jewish places of worship, in privately owned houses, at grave sites of saints and loved ones, and even outdoors. In Rome, there are indications that early Christians met in other public spaces such as warehouses or apartment buildings. The domus ecclesiae or house church was a large private house--not just the home of an extended family, its slaves, and employees--but also the household’s place of business. Such a house could accommodate congregations of about 100-150 people. 3rd-century house church in Dura-Europos, in what is now Syria CHURCH BUILDINGS In the second half of the 3rd century, Christians began to construct their first halls for worship (aula ecclesiae). -

Gothic Beyond Architecture: Manchester’S Collegiate Church

Gothic beyond Architecture: Manchester’s Collegiate Church My previous posts for Visit Manchester have concentrated exclusively upon buildings. In the medieval period—the time when the Gothic style developed in buildings such as the basilica of Saint-Denis on the outskirts of Paris, Île-de-France (Figs 1–2), under the direction of Abbot Suger (1081–1151)—the style was known as either simply ‘new’, or opus francigenum (literally translates as ‘French work’). The style became known as Gothic in the sixteenth century because certain high-profile figures in the Italian Renaissance railed against the architecture and connected what they perceived to be its crude forms with the Goths that sacked Rome and ‘destroyed’ Classical architecture. During the nineteenth century, critics applied Gothic to more than architecture; they located all types of art under the Gothic label. This broad application of the term wasn’t especially helpful and it is no-longer used. Gothic design, nevertheless, was applied to more than architecture in the medieval period. Applied arts, such as furniture and metalwork, were influenced by, and followed and incorporated the decorative and ornament aspects of Gothic architecture. This post assesses the range of influences that Gothic had upon furniture, in particular by exploring Manchester Cathedral’s woodwork, some of which are the most important examples of surviving medieval woodwork in the North of England. Manchester Cathedral, formerly the Collegiate Church of the City (Fig.3), see here, was ascribed Cathedral status in 1847, and it is grade I listed (Historic England listing number 1218041, see here). It is medieval in foundation, with parts dating to between c.1422 and 1520, however it was restored and rebuilt numerous times in the nineteenth century, and it was notably hit by a shell during WWII; the shell failed to explode. -

GPR Survey: the Nave

The Ground Penetrating Radar survey in the Nave of Reading Abbey Church John Mullaney (December 2016) The West End The anomalous GPR lines at the west end of the nave of the Abbey church. When we first saw the GPR findings we were surprised to see the results at the west end of the nave (in the Forbury) which Stratascan classified as probably archaeology feature(s) –possibly related to the Abbey. — light blue on the map. I have marked these with two black arrows. probably archaeology feature –possibly related to the Abbey First of all it should be noted that these may be connected with some features totally unrelated to the Abbey. For instance they could be part of the defence system constructed during the 17th century Civil War. They may be footings of one of the walls that we know surrounded the late 18th century school next to the Inner Gateway (Jane Austen’s school). It is possible that they are part of the foundations for some buildings, such as the greenhouses, that appear to have been erected in the Forbury botanic gardens during the second half of the 19th century. However I have looked into the possibility that they may in fact be related to the Abbey; in other words whether there may be some explanation for their existence as part of the Abbey. I must emphasise that any one, or none, of the above may be the explanation and without intrusive archaeology or the discovery of some documentation relating to them, it is unlikely that we will ever know what they truly represent. -

Aberdeen History Trail the City Through Its Historical Times

Aberdeen History Trail The city through its historical times #aberdeentrails #aberdeentrails Aberdeen is bursting full of history! From its ancient origins to medieval burghs and King Robert The Bruce, from the Jacobite connections to the expansion in the Edwardian and Victorian times, the ‘Silver City by the Golden Sands’ has a long, important, and interesting history with many of its people contributing to the wider world. The city started out as three separate royal burghs – Old Aberdeen, New Aberdeen and Torry plus the parish of Woodside – which expanded and merged together to form the city as a whole. There was a major expansion in the Georgian, Edwardian and Victorian eras as the city made its first fortunes based on fishing, granite quarrying and shipbuilding and many of the grand buildings were built during these times. It also included the main thoroughfare, Union Street, which was raised up away from the mud and dirt and built on a series of bridges – it was such a major project it almost bankrupted the city! Enjoy exploring our beautiful city and finding out about its history! Picture Credits All images © Aberdeen City Council unless otherwise stated Introduction and all entries: This trail is extensively illustrated by period pictures from the Silver City Vault. The majority are from this source and we’re very grateful for their use and the help from this service. They are all used courtesy of Aberdeen City Libraries/Silver City Vault www.silvercityvault.org.uk 4: Used courtesy of the photographer © Roddy Millar. 14: Thomas Blake Glover courtesy Nagasaki Museum of History and Culture Left, New & Old Aberdeen maps: Details from Parson Gordon’s map of 1661. -

Scotland ; Picturesque, Historical, Descriptive

250 SCOTLAND DELINEATED. the very name of Macgregor, and rendering the meeting of four of them together at one time a capital crime. Other enactments against them were occasionally renewed, and those proscriptions were in force until the eighteenth century. In 1715 occurred the "Loch Lomond Expedition," against the Macgregors, who, in defiance of the laws against them continued their marauding expeditions under the celebrated Rob Roy Macgregor, and were in reality public robbers. They had seized all the boats on the lake, invaded the island of Inch- Murrin, killed many of the deer belonging to the Duke of Montrose, and committed other excesses. A strong force of volunteers from towns in the counties of Renfrew and Ayr was sent against them to recover the boats, assisted by about one hundred seamen from the ships of war in the Clyde, commanded by seven officers. They sailed up the Leven, and were drawn three miles 4n the course by horses. The contemporary account quaintly states that when " the pinnaces and boats within the mouth of the Loch had spread their sails, and the men on the shore had ranged themselves in order, marching along the side of the Loch for scouring the coast, they made altogether so very fine an appearance as had never been seen in that place before, and might have gratified even a curious person." The Macgregors, however, had disappeared, and the volunteers returned to Dunbarton, after securing the captured booty, without any demonstration of their courage. The Leven is the discharge from Loch Lomond, and traverses the beautiful vale nearly six miles to the Clyde at Dunbarton Castle. -

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack

Blackadder Goes Forth Audition Pack Key Dates Audition Dates: • Tuesday 8 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 12 th May – 10.30am – 5.00pm • Sunday 13 th May – 10:00am – 3.00pm Recalls (if required): • Friday 18 th May – 6:00 – 10:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) • Saturday 19 th May – 10:00am – 1:00pm (Everyman Clubroom) Actors who are successfully cast need to understand that they MUST be available for all the following key dates • Technical Rehearsal: Sunday 11 th November (cast need to be available all day) • Dress Rehearsal: Monday 12 th November (evening) • Performance Dates: Tuesday 13 th – Saturday 17 th November; Evening Performances at 7.30pm, Saturday matinee at 2.30pm Rehearsal Nights Rehearsals will begin w/c Monday 3 rd September. Exact rehearsal nights will be confirmed nearer the time but are quite likely to be Tuesdays, Thursdays and Sundays. Not all cast will be required for every rehearsal. Plot Blackadder Goes Forth is set in 1917 on the Western Front in the trenches of World War I. Captain Edmund Blackadder is a professional soldier in the British Army who, until the outbreak of the Great War, has enjoyed a relatively danger-free existence fighting natives who were usually "two feet tall and armed with dried grass". Finding himself trapped in the trenches with another "big push" planned, his concern is to avoid being sent over the top to certain death. The show thus chronicles Blackadder's attempts to escape the trenches through various schemes, most of which fail due to bad fortune, misunderstandings and the general incompetence of his comrades. -

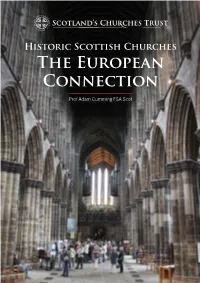

The European Connection

Historic Scottish Churches The European Connection Prof Adam Cumming FSA Scot Adam Cumming Talk “It is often assumed that Scotland took its architectural lead from England, but this is not completely true, Scotland had its own links across Europe, and these developed and changed with time.” cotland has many medieval Glasgow Cathedral which can be churches though not all are shown to have architectural links well known. They deserve across Europe. Sgreater awareness. Many The early Scottish church, that of are ruined but many are not, and Ninian and Columba (as well as many others often survive in some form in others), was part of the early church adapted buildings. before the great schism 1054. It was It is often assumed that Scotland organised a little like the Orthodox took its architectural lead from Churches now. The church below is England, but this is not completely that of Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, an true, Scotland had its own links Orthodox community and similar in across Europe, and these developed plan to early Scottish ones with the and changed with time. The changes church in the centre of the complex. were usually a response to politics It is often described as Celtic and trade. This is of course reflected which is a later description but does in the buildings across Scotland. emphasise a common base with It can be argued that these form a Ireland and Wales etc. There was distinctive part of European culture a great deal of movement across with regional variations. Right is northern Europe and it retained close links with Ireland and elsewhere via ‘Schottenkloster’ and other mission centres. -

Old West Kirk of Greenock 15911591----18981898

The Story of The Old West Kirk Of Greenock 15911591----18981898 by Ninian Hill Greenock James McKelvie & Sons 1898 TO THE MEMORY OF CAPTAIN CHARLES M'BRIDE AND 22 OFFICERS AND MEN OF MY SHIP THE "ATALANTA” OF GREENOCK, 1,693 TONS REGISTER , WHO PERISHED OFF ALSEYA BAY , OREGON , ON THE 17TH NOVEMBER , 1898, WHILE THESE PAGES ARE GOING THROUGH THE PRESS , I DEDICATE THIS VOLUME IN MUCH SORROW , ADMIRATION , AND RESPECT . NINIAN HILL. PREFACE. My object in issuing this volume is to present in a handy form the various matters of interest clustering around the only historic building in our midst, and thereby to endeavour to supply the want, which has sometimes been expressed, of a guide book to the Old West Kirk. In doing so I have not thought it necessary to burden my story with continual references to authorities, but I desire to acknowledge here my indebtedness to the histories of Crawfurd, Weir, and Mr. George Williamson. My heartiest thanks are due to many friends for the assistance and information they have so readily given me, and specially to the Rev. William Wilson, Bailie John Black, Councillor A. J. Black, Captain William Orr, Messrs. James Black, John P. Fyfe, John Jamieson, and Allan Park Paton. NINIAN HILL. 57 Union Street, November, 1898. The Story of The Old West Kirk The Church In a quiet corner at the foot of Nicholson Street, out of sight and mind of the busy throng that passes along the main street of our town, hidden amidst high tenements and warehouses, and overshadowed at times by a great steamship building in the adjoining yard, is to be found the Old West Kirk. -

Genealogical History of the House of Wishart

MEMOIR OF GEORGE WISHART. 329 GENEALOGICAL HISTORY OF THE HOUSE OF WISHART. NlSBET's statement as to the family of Wishart having derived descent from Robert, an illegitimate son of David, Earl of Huntingdon, who was styled Guishart on account of his heavy slaughter of the Saracens, is an evident fiction.* The name Guiscard, or Wiscard, a Norman epithet used to designate an adroit or cunning person, was conferred on Robert Guiscard, son of Tancrede de Hauterville of Nor- mandy, afterwards Duke of Calabria, who founded the king- dom of Sicily. This noted warrior died on the 27th July 1085. His surname was adopted by a branch of his House, and the name became common in Normandy and throughout France. Guiscard was the surname of the Norman kings of Apulia in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. John Wychard is mentioned as a small landowner in the Hundred de la Mewe, Buckinghamshire, in the reign of Henry III. (I2i6-i272)/1- During the same reign and that of Edward I. (1272-1307), are named as landowners, Baldwin Wyschard or Wistchart, in Shropshire; Nicholas Wychard, in Warwickshire ; Hugh Wischard, in Essex; and William Wischard, in Bucks.j In the reign of Edward I. Julian Wye- chard is named as occupier of a house in the county of Oxford.§ A branch of the House of Wischard obtained lands in Scotland some time prior to the thirteenth century. John Wischard was sheriff of Kincardineshire in the reign of Alexander II. (1214-1249). In an undated charter of this monarch, Walter of Lundyn, and Christian his wife, grant to the monks of Arbroath a chalder of grain, " pro sua frater- nitate," the witnesses being John Wischard, " vicecomes de • Nisbet's System of Heraldry, Edin., 1816, folio, vol. -

Modern Alternative Popes*

Modern Alternative Popes* Magnus Lundberg Uppsala University The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) is arguably the most important event in modern Catholicism, and a major act on the twentieth-century religious scene at large. On several points, the conciliar fathers made changes in how the Catholic Church perceived the modern world. The language in the decrees was different from earlier councils’, and the bishops opened up for ecumenism and interreligious dialogue, seeing at least “seeds of truth” in other religious traditions. The conciliar fathers also voted in favour of liberty of religion, as meaning something more than the right to practise Catholic faith. A very concrete effect of the Council was the introduction of the New Mass Order (Novus Ordo Missae) in 1969 that replaced the traditional Roman rite, decreed by Pius V in 1570. Apart from changes in content, under normal circumstances, the new mass should be read in the vernacular, not in Latin as before. Though many Catholics welcomed the reforms of Vatican II, many did not. In the period just after the end of the Council, large numbers of priests and nuns were laicized, few new priest candidates entered the seminaries, and many laypeople did not recognize the church and the liturgy, which they had grown up with. In the post- conciliar era, there developed several traditionalist groups that criticized the reforms and in particular the introduction of the Novus Ordo. Their criticism could be more or less radical, and more or less activist. Many stayed in their parishes and attended mass there, but remained faithful to traditional forms of devotions and paid much attention to modern Marian apparitions. -

F 1 ¥ IMTIIA LBM Im S I- Li II I; • J .Ij M {;'11**Fi,*' •> {- Wy

■j XNIClpTS || J'OjGCM C»F ■ 1 ¥ IMTIIA LBM im S i- li II 11 I; • j .ij M {;' **f i,*’ •> {- wy -fag ScS. SKS 155 SCOTTISH HISTORY SOCIETY FOURTH SERIES VOLUME 19 The Knights of St John of Jerusalem in Scotland THE KNIGHTS OF ST JOHN OF JERUSALEM IN SCOTLAND edited by Ian B. Cowan, ph.d. P. H. R. Mackay, ph.d. and Alan Macquarrie, ph.d. ★ ★ EDINBURGH printed for the Scottish History Society by CLARK CONSTABLE (1982) LTD 1983 Scottish History Society 1983 ISBN o 906245 03 6 Printed in Great Britain 1 L i. B " ^l PREFACE What probably began for Angus Macdonald as a boyhood interest in the choir at Torphichen developed into a persistent desire to write the history of the Knights Hospitallers in Scotland. For upwards of thirty years he collected material - references in printed volumes of public and family records, writings of other scholars, and a collection of photostats of original documents gathered from a wide variety of sources. In an unpublished essay he made a first attempt to set out in order the principal fruits of his research to date, but, being far from satisfied with the result, he projected a book which would give scope for much more detailed treatment. Work on this was interrupted by Dr Macdonald’s sudden death in September 1966. His papers were deposited with the Scottish History Society by his executors and were transferred for safe- keeping to the Scottish Record Office. A thorough examination of the papers has revealed a wealth of material illustrative of every aspect of the activity of the Knights Hospitallers in Scotland, abundant evidence of Dr Macdonald’s activity in collecting and annotating, but of his own writing there remains only the typescript of the essay and a second and much shorter typescript of a paper read to the West Lothian History Society.