St Machar's Cathedral Transepts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Talking Gothic! What Do We Mean by Gothic Architecture and How Can We Identify It?

Talking Gothic! What do we mean by Gothic architecture and how can we identify it? ‘Gothic’ is the name we give to a style of architecture from the Middle Ages. It is usually thought to have begun near Paris in the middle of the 1100s and, from there, it spread throughout Europe and continued into the 16th century. There are many marvellous examples of Gothic buildings throughout Scotland: from Elgin Cathedral in Moray, through amazing buildings like Glasgow Cathedral, Paisley Abbey and Edinburgh St Giles, down to Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders. All of these, and more, are well worth a visit! Gothic architecture developed from an earlier style we call Romanesque. Buildings made in the Romanesque style often have rounded arches on their (usually comparatively small) windows and doors, thick columns and walls, lots of ornamental patterns, and shorter structures than the buildings which came later. Dunfermline Abbey is a great example of a Romanesque building in Scotland. The people who paid for the earliest Gothic buildings expressed a wish to transport worshippers to a kind of Heaven on Earth by building higher and brighter churches. What emerged is what we now describe as Gothic. Fashions changed throughout the time that Gothic was the predominant style, and it also varied from place to place. However, the Classical revival made popular as part of the Italian Renaissance largely replaced the Gothic style, and it wasn’t fashionable again until the 19th century. During the Romantic Movement Medieval literature, arts and crafts enjoyed renewed popularity. As a result, Glasgow Cathedral was begun in the Gothic elements can be seen today in the churches, public buildings, and late 12th century and was at the hub of the Medieval city. -

ASCI Newsl Oct 2017

+ Scotland! BOARD MEMBERS ASCI Newsletter President Karon Korp Vice President October 2017 Secretary Alice Keller Promoting International Partnerships Treasurer Jackie Craig Past President Andrew Craig Membership Bunny Cabaniss Social Chair Jacquie Nightingale Special Projects Gwen Hughes, Ken Richards Search Russ Martin Newsletter Jerry Plotkin Publicity / Public Relations Jeremy Carter Fund Development Marjorie McGuirk Giving Society Gwen Hughes George Keller Vladikavkaz, Russia Constance Richards San Cristóbal de las Casas, Mexico Lori Davis Saumur, France Jessica Coffield Karpenisi, Greece Sophie Mills, Andrew Craig New Scottish sister city! Valladolid, Mexico Sybil Argintar A hug to seal the deal! Osogbo, Nigeria Sandra Frempong Katie Ryan Follow ASCI activities on the web! Dunkeld-Birnam Rick Lutovsky, Doug Orr http://ashevillesistercities.org Honorary Chairman Mayor Esther Manheimer Like us on Facebook – keep up with ASCI news. Mission Statement: Asheville Sister Cities, Inc. promotes peace, understanding, cooperation and sustainable partnerships through formalized agreements between International cities and the City of Asheville, North Carolina. Website: www.ashevillesistercities.org ASHEVILLE SISTER CITIES NEWSLETTER – OCTOBER 2017 page 2 On the cover: Surrounded by friends, Birnam-Dunkeld Committee Chair for Asheville Fiona Ritchie celebrates their new sister city with Asheville Mayor Esther Manheimer. Message from the President by Karon Korp What an exciting Fall line-up we have, on the heels of a very busy summer! Our group from Asheville was warmly received by our new sister cities of Dunkeld and Birnam, Scotland in August. The celebration and signing event we held in September at Highland Brewing gave everyone a taste of the wonderful friendships now formed as we hosted our Scottish guests. -

The Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517

Cochran-Yu, David Kyle (2016) A keystone of contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/7242/ Copyright and moral rights for this thesis are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Glasgow Theses Service http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] A Keystone of Contention: the Earldom of Ross, 1215-1517 David Kyle Cochran-Yu B.S M.Litt Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Ph.D. School of Humanities College of Arts University of Glasgow September 2015 © David Kyle Cochran-Yu September 2015 2 Abstract The earldom of Ross was a dominant force in medieval Scotland. This was primarily due to its strategic importance as the northern gateway into the Hebrides to the west, and Caithness and Sutherland to the north. The power derived from the earldom’s strategic situation was enhanced by the status of its earls. From 1215 to 1372 the earldom was ruled by an uninterrupted MacTaggart comital dynasty which was able to capitalise on this longevity to establish itself as an indispensable authority in Scotland north of the Forth. -

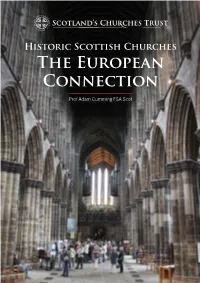

The European Connection

Historic Scottish Churches The European Connection Prof Adam Cumming FSA Scot Adam Cumming Talk “It is often assumed that Scotland took its architectural lead from England, but this is not completely true, Scotland had its own links across Europe, and these developed and changed with time.” cotland has many medieval Glasgow Cathedral which can be churches though not all are shown to have architectural links well known. They deserve across Europe. Sgreater awareness. Many The early Scottish church, that of are ruined but many are not, and Ninian and Columba (as well as many others often survive in some form in others), was part of the early church adapted buildings. before the great schism 1054. It was It is often assumed that Scotland organised a little like the Orthodox took its architectural lead from Churches now. The church below is England, but this is not completely that of Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, an true, Scotland had its own links Orthodox community and similar in across Europe, and these developed plan to early Scottish ones with the and changed with time. The changes church in the centre of the complex. were usually a response to politics It is often described as Celtic and trade. This is of course reflected which is a later description but does in the buildings across Scotland. emphasise a common base with It can be argued that these form a Ireland and Wales etc. There was distinctive part of European culture a great deal of movement across with regional variations. Right is northern Europe and it retained close links with Ireland and elsewhere via ‘Schottenkloster’ and other mission centres. -

Old West Kirk of Greenock 15911591----18981898

The Story of The Old West Kirk Of Greenock 15911591----18981898 by Ninian Hill Greenock James McKelvie & Sons 1898 TO THE MEMORY OF CAPTAIN CHARLES M'BRIDE AND 22 OFFICERS AND MEN OF MY SHIP THE "ATALANTA” OF GREENOCK, 1,693 TONS REGISTER , WHO PERISHED OFF ALSEYA BAY , OREGON , ON THE 17TH NOVEMBER , 1898, WHILE THESE PAGES ARE GOING THROUGH THE PRESS , I DEDICATE THIS VOLUME IN MUCH SORROW , ADMIRATION , AND RESPECT . NINIAN HILL. PREFACE. My object in issuing this volume is to present in a handy form the various matters of interest clustering around the only historic building in our midst, and thereby to endeavour to supply the want, which has sometimes been expressed, of a guide book to the Old West Kirk. In doing so I have not thought it necessary to burden my story with continual references to authorities, but I desire to acknowledge here my indebtedness to the histories of Crawfurd, Weir, and Mr. George Williamson. My heartiest thanks are due to many friends for the assistance and information they have so readily given me, and specially to the Rev. William Wilson, Bailie John Black, Councillor A. J. Black, Captain William Orr, Messrs. James Black, John P. Fyfe, John Jamieson, and Allan Park Paton. NINIAN HILL. 57 Union Street, November, 1898. The Story of The Old West Kirk The Church In a quiet corner at the foot of Nicholson Street, out of sight and mind of the busy throng that passes along the main street of our town, hidden amidst high tenements and warehouses, and overshadowed at times by a great steamship building in the adjoining yard, is to be found the Old West Kirk. -

Church and Community in Later Medieval Glasgow: an Introductory Essay*

Church and Community in Later Medieval Glasgow: An Introductory Essay* by John Nelson MINER** Later medieval Glasgow has not yet found its place in urban history, mainly because most writers have concentrated on the modern, industrial period and those historians who have devoted attention to the pre-industrial city have failed to reach any consensus as to the extent of its modest expansion in the period circa 1450 to 1550 or the reasons behind it. In this study, the specific point is made that it is the ecclesiastical structure of Glasgow that will best serve towards an appreciation of the total urban community. This central point has not so far been developed even in the use of the published sources, which have to be looked at afresh in the above context. L'histoire urbaine ne s'est pas jusqu'ii maintenant penchee sur Ia situation de Glasgow au bas moyen age; en effet, Ia plupart des travaux s'interessent avant tout au Glasgow industriel et les historiens qui ont etudie Ia ville preindustrielle n' ont pu s' entendre sur l'ampleur et les raisons de sa modeste expansion entre 1450 et 1550 environ. Nous af firmons ici que ce sont les structures ecc/esiastiques presentes ii Glasgow qui autorisent /'evaluation Ia plus juste de Ia collectivite urbaine dans son ensemble. Cette dimension pri mordiale n'a pas meme ete degagee du materiel contenu dans les sources imprimees, qu'il faut reexaminer en consequence. Modem Glasgow reveals as little of its medieval past to the visitor as it does to its own inhabitants. -

Macg 1975Pilgrim Web.Pdf

-P L L eN cc J {!6 ''1 { N1 ( . ~ 11,t; . MACGRl!OOR BICENTDmIAL PILGRIMAGE TO SCOTLAND October 4-18, 197.5 sponsored by '!'he American Clan Gregor Society, Inc. HIS'lORICAL HIGHLIGHTS ABO ITINERARY by Dr. Charles G. Kurz and Claire MacGregor sessford Kurz , Art work by Sue S. Macgregor under direction of R. James Macgregor, Chairman MacGregor Bicentennial Pilgrimage booklets courtesy of W. William Struck, President Ambassador Travel Service Bethesda, Md • . _:.I ., (JUI lm{; OJ. >-. 8IaIYAt~~ ~~~~ " ~~f. ~ - ~ ~~.......... .,.; .... -~ - 5 ~Mll~~~. -....... r :I'~ ~--f--- ' ~ f 1 F £' A:t::~"r:: ~ 1I~ ~ IftlC.OW )yo X, 1.. 0 GLASGOw' FOREWORD '!hese notes were prepared with primary emphasis on MaoGregor and Magruder names and sites and their role in Soottish history. Secondary emphasis is on giving a broad soope of Soottish history from the Celtio past, inoluding some of the prominent names and plaoes that are "musts" in touring Sootland. '!he sequenoe follows the Pilgrimage itinerary developed by R. James Maogregor and SUe S. Maogregor. Tour schedule time will lim t , the number of visiting stops. Notes on many by-passed plaoes are information for enroute reading ani stimulation, of disoussion with your A.C.G.S. tour bus eaptain. ' As it is not possible to oompletely cover the span of Scottish history and romance, it is expected that MacGregor Pilgrims will supplement this material with souvenir books. However. these notes attempt to correct errors about the MaoGregors that many tour books include as romantic gloss. October 1975 C.G.K. HIGlU.IGHTS MACGREGOR BICmTENNIAL PILGRIMAGE TO SCOTLAND OCTOBER 4-18, 1975 Sunday, October 5, 1975 Prestwick Airport Gateway to the Scottish Lowlands, to Ayrshire and the country of Robert Burns. -

Download Download

THE MONUMENTAL EFFIGIES OF SCOTLAND. 329 VI. THE MONUMENTAL EFFIGIES OF SCOTLAND, FROM THE THIRTEENTH TO THE FIFTEENTH CENTURY. BY ROBERT BRYDALL, F.S.A. SOOT. The custom of carving monumental effigies in full relief does not seem to have come into vogue in Scotland till the thirteenth century—this being also the case in England. From the beginning of that period the art of the sculptor had made great progress both in Britain and on the Continent. At the close of the twelfth century, artists were beginning to depart from the servile imitation of the work of earlier carvers, to think more for themselves, and to direct their attention to nature ; more ease began to appear in rendering the human figure; form was more gracefully expressed, and drapery was treated with much greater freedom. When the fourteenth century drew towards its end, design in sculpture began to lose something of the purity of its style, more attention being given to detail than to general effect; and at the dawn of the sixteenth century, the sculptor, in Scotland, began to degenerate into a mere carver. The incised slab was the earliest form of the sculptured effigy, a treat- ment of the figure in flat relief intervening. The incised slabs, as well as those in flat relief, which were usually formed as coffin-lids, did not, however, entirely disappear on the introduction of the figure in full relief, examples of both being at Dundrennan Abbey and Aberdalgie, as well as elsewhere. An interesting example of the incised slab was discovered at Creich in Fife in 1839, while digging a grave in the old church; on this slab two figures under tabernacle-work are incised, with two shields bearing the Barclay and Douglas arms : hollows have been sunk for the faces and hands, which were probably of a different material; and the well cut inscription identifies the figures as those of David Barclay, who died in 1400, and his wife Helena Douglas, who died in 1421. -

Lives of Eminent Men of Aberdeen

NYPL RESEARCH LIBRARIES 3 3433 08253730 3 - - j : EMINENT MEN OF ABERDEEN. ABERDEEN: PRINTED AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS, BY D. CHALMERS AND CO. LIVES OF EMINENT MEN OF ABERDEEN. BY JAMES BRUCE ABERDEEN : L. D. WYLLIE & SON S. MACLEAN ; W. COLLIE ; SMITH ; ; AND J. STRACHAN. W. RUSSEL ; W. LAURIE ; EDINBURGH: WILLIAM TAIT ; GLASGOW: DAVID ROBERTSON; LONDON : SMITH, ELDER, & CO. MDCCCXLI. THE NEW r TILDEN FOUr R 1, TO THOMAS BLAIKIE, ESQ., LORD PROVOST OF ABERDEEN, i's Folum? IS INSCRIBED, WITH THE HIGHEST RESPECT AND ESTEEM FOR HIS PUBLIC AND PRIVATE CHARACTER, AND FROM A SENSE OF THE INTEREST WHICH HE TAKES IN EVERY THING THAT CONCERNS THE HONOUR AND WELFARE OF HIS NATIVE CITY, BY HIS MUCH OBLIGED AND MOST OBEDIENT SERVANT, JAMES BRUCE. A 2 CONTENTS PAGE. ( JOHN BARBOU'R . 1 BISHOP ELPHINSTONE 22 BISHOP GAVIN DUXBAR . .57 DR. THOMAS MORISON . 76 GILBERT GRAY . 81 BISHOP PATRICK FORBES . 88 DR. DUNCAN LIDDEL . .115 GEORGE JAMIESON . 130 BISHOP WILLIAM FORBES . 152 DR. ARTHUR JOHNSTON . 171 EDWARD RABAN ... .193 DR. WILLIAM GUILD . 197 ALEXANDER ROSS . 225 GEORGE DALGARNO . 252 JOHN SPALDING . .202 HENRY SCOUGAL . 270 ROBERT GORDON . 289 PRINCIPAL BLACKWELL 303 ELIZABETH BLACKWELL . 307 DR. CAMPBELL . .319 DR. BEATTIE . 305 DR. HAMILTON . 3*1 DR. BROWN . 393 PREFACE IN offering this volume to the public, the writer trusts, that, with all its imperfections, it will be found not uninteresting to his townsmen, or, perhaps, to the general reader. At least it had frequently occurred to him, that an amusing and instructive book might be made on the subject which he has handled. -

St Columba Poetry

ntroduction The 7th December 2020 marked the 1,500th anniversary of the birth of St Columba, or Colmcille. A self-imposed exile from Ireland, Columba was a key figure in the early Christianity of the Scottish mainland and western isles and left an indelible mark on the landscape. From the founding of Iona Abbey to one of the earliest sightings of the Loch Ness Monster, his legacy is both physical and cultural. Fleeing Ireland after a dispute regarding religious texts, Columba was known as a scribe and has been linked (although likely erroneously) to one of the earliest illuminated manuscripts of Ireland. He was also a protector of poets and as the Patron Saint of Poetry, what better way to celebrate his varied impact than with the creation of poetry that explores his connection to Scotland and its historic environment. Poet in Residence Alex Aldred spent twenty weeks with us, exploring Columba’s relationship to our sites and the Scottish landscape in order to create a new body of works in response to Columba’s Scotland. We hope that these works inspire you to create your own responses to the historic environment and to refect upon the ways that landscape, heritage and the arts intertwine. lex Aldred Alex Aldred lives and writes in Edinburgh, Scotland. He has an MA in creative writing from Lancaster University, and is currently working towards a PhD in creative writing at the University of Edinburgh inspired by and responding to maps of the City of Edinburgh. Alex’s residency was generously funded by the Scottish Graduate School of Arts and Humanities. -

Churches & Places of Worship in Scotland Aberdeen Unitarian Church

Churches & Places of Worship in Scotland Aberdeen Unitarian Church - t. 01224 644597 43a Skene Terrace, Aberdeen, Aberdeenshire, AB10 1RN, Scotland Aberfoyle Church of Scotland - t. 01877 382391 Lochard Road, Aberfoyle near Stirling, Stirlingshire, FK8 3SZ, Scotland All Saints Episcopal Church - t. 01334 473193 North Castle Street, St Andrews, Fife, KY16 9AQ, Scotland Allan Park South Church - t. 01786 471998 Dumbarton Road, Stirling, Stirlingshire, FK8 2LQ, Scotland Almond Vineyard Church - t. 0131 476 6640 Craigs Road, Edinburgh, Midlothian, EH12 8NH, Scotland Alyth Parish Church - t. 01828 632104 Bamff Road, Alyth near Blairgowrie, Perthshire, PH11 8DS, Scotland Anstruther Parish Church School Green, Anstruther, Fife, KY10 3HF, Scotland Archdiocese of Glasgow - t. 0141 226 5898 196 Clyde Street, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, G1 4JY, Scotland Augustine United Church - t. 0131 220 1677 41 George IV Bridge, Edinburgh, Midlothian, EH1 1EL, Scotland Bible Baptist Church - t. 01738 451313 4 Weir Place, Perth, Perthshire, PH1 3GP, Scotland Broom Church - t. 0141 639 3528 Mearns Road, Newton Mearns, Renfrewshire, G77 5EX, Scotland Broxburn Baptist Church - t. 01506 209921 Freeland Avenue, Broxburn, West Lothian, EH52 6EG, Scotland Broxburn Catholic Church - t. 01506 852040 34 West Main Street, Broxburn, West Lothian, EH52 5RJ, Scotland The Bruce Memorial Church - t. 01786 450579 St Ninians Road, Cambusbarron near Stirling, Stirlingshire, FK7 9NU, Scotland Cairns Church of Scotland - t. 0141 956 4868 11 Buchanan Street, Milngavie, Dunbartonshire, G62 8AW, Scotland Calvary Chapel Edinburgh - t. 0131 660 4535 Danderhall Community Centre, Newton Church Road, Danderhall near Dalkeith, Midlothian, EH22 1LU, Scotland Calvary Chapel Stirling - t. 07940 979503 2-4 Bow Street, Stirling, Stirlingshire, FK8 1BS, Scotland Catholic Church of the Sacred Heart - t. -

Involvement in the 1715 Jacobite Rebellion /11

VOLUME 9 ISSUE 1 WINTER 2017 clan STRACHAN Clachnaben! involvement in the 1715 Jacobite rebellion /11 Highland News & bagpipes / 5 Notes / 19 The Wolf of Shetland ponies Badenoch / 8 / 21 NEWSLETTER FOR THE CLAN STRACHAN SCOTTISH HERITAGE SOCIETY, INC. NON TIMEO SED CAVEO clan STRACHAN Clachnaben! President’s address Newsletter for the Hello the Clan, Clan Strachan Scottish Heritage Another year has come and gone and I hope that all is well with each of Society, Inc. you. I, for one, look forward to 2017. 30730 San Pascual Road We tried to hold our annual meeting in December but time and events Temecula, CA 92591 got in the way. We will try to get it done early in the year. One of those United States of America reasons was Jim’s daughter, Alicia, was married to a fine young Marine named Aaron . it was a great wedding and I know we all wish the happy Phone: 951-760-8575 couple a grand life together. Email: [email protected] After a long wait, we finally got our parade We’re on the web! banners completed and www.clanstrachan.org mailed out to those who requested them Incorporated in 2008, the Clan Strachan Scottish Heritage Society, Inc. was orga- . see the picture nized for exclusively charitable, educa- tional and scientific purposes within the provided here . they meaning of Section 501(c)(3) of the Internal came out looking good Revenue Code of 1986, or the correspond- ing provision of any future United States and will be a splash of Internal Revenue Law, including, for such purposes, the making of distributions to color for Clan Parades.