Church and Community in Later Medieval Glasgow: an Introductory Essay*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Galloway's Bishop-Elect in Prayer Call

Year for CAMPAIGN LIFE SUPREME KNIGHT CONSECRATED 2017 launched honour LIFE begins at ladies returns to on Sunday. pro-life lunch. Glasgow. Page 3 Page 2 Page 8 No 5597 BLESSINGS ON THE FEAST OF ST ANDREW ON NOVEMBER 30 Friday November 28 2014 | £1 EUROPE TOLD BY POPE FRANCIS TO RESPECT LIFE By Ian Dunn POPE Francis told members of the European Parliament on Tuesday that they must end the treatment of ‘the unborn, terminally ill, and the elderly’ as objects and embrace a new fairer immigration policy of acceptance. In a second speech the same day, the Pope also told the Council of Europe that human trafficking was the new slavery of our age, depriving its victims of all dignity. The Holy Father was speaking at the European Parliament in Strasbourg during a brief visit meant to highlight his vision for Europe a quarter-century after St John Paul II travelled there to address a continent still divided by the Iron Curtain. “Despite talk of human rights, too many people are treated as objects in Europe: unborn, terminally ill, and the elderly,” the Pope told MEPs. “We’re too tempted to throwaway lives we don’t see as ‘useful.’ Upholding the dignity of the person means acknowledging the value of the gift of human life.” He said that ‘killing [children]… before they’re born is the great mistake that happens when technology is allowed to take over’ and is ‘the Pope Francis shakes hands with Martin Schulz, inevitable consequence of a throwaway culture.’ president of the European Parliament, while visiting the European Parliament in Strasbourg I Continued on page 6 Galloway’s bishop-elect in prayer call I Fr William Nolan, ‘gobsmacked’ over Pope Francis’ appointment, asks for parishioners to pray for him By Ian Dunn seeds of Faith so long ago,” The new bishop added that his experience in many pastoral situations, He said he was glad that his ordination parishioners were delighted for him. -

Talking Gothic! What Do We Mean by Gothic Architecture and How Can We Identify It?

Talking Gothic! What do we mean by Gothic architecture and how can we identify it? ‘Gothic’ is the name we give to a style of architecture from the Middle Ages. It is usually thought to have begun near Paris in the middle of the 1100s and, from there, it spread throughout Europe and continued into the 16th century. There are many marvellous examples of Gothic buildings throughout Scotland: from Elgin Cathedral in Moray, through amazing buildings like Glasgow Cathedral, Paisley Abbey and Edinburgh St Giles, down to Melrose Abbey in the Scottish Borders. All of these, and more, are well worth a visit! Gothic architecture developed from an earlier style we call Romanesque. Buildings made in the Romanesque style often have rounded arches on their (usually comparatively small) windows and doors, thick columns and walls, lots of ornamental patterns, and shorter structures than the buildings which came later. Dunfermline Abbey is a great example of a Romanesque building in Scotland. The people who paid for the earliest Gothic buildings expressed a wish to transport worshippers to a kind of Heaven on Earth by building higher and brighter churches. What emerged is what we now describe as Gothic. Fashions changed throughout the time that Gothic was the predominant style, and it also varied from place to place. However, the Classical revival made popular as part of the Italian Renaissance largely replaced the Gothic style, and it wasn’t fashionable again until the 19th century. During the Romantic Movement Medieval literature, arts and crafts enjoyed renewed popularity. As a result, Glasgow Cathedral was begun in the Gothic elements can be seen today in the churches, public buildings, and late 12th century and was at the hub of the Medieval city. -

Green Light Signals Quest for Auxiliary

Lord, Let Glasgow Flourish by the preaching of Thy Word and the praising of Thy Name JULY 2015 JOURNAL OF THE ARCHDIOCESE OF GLASGOW 70p Joie de vivre! A SPIRIT of joy filled St Andrew’s Cathedral as children and young people with additional support needs joined Archbishop Philip Tartaglia for Mass. The theme ‘Rejoice’ reflected the Gospel passage of Mary’s visit to her cousin Elizabeth – whose child in her womb leapt for joy. The Archbishop spoke of the gifts of life and love and the great joy which the births of John the Baptist and Jesus brought to the world. He encouraged the young people to rejoice and reflect that joy in caring for others and looking after the world. Glasgow Lord Provost Sadie Docherty joined in the celebrations. Picture by Paul McSherry Green light Caritas Glasgow to get signals quest Award another bishop for auxiliary Pope Francis has agreed diocesan bishop’s closest col - with Bishop Joseph Devine the green light to his request, By Vincent Toal laborator, he is expected to be who moved to Motherwell in Archbishop Tartaglia has in - to provide an auxiliary involved in all pastoral proj - 1983. Bishop John Mone then vited people to write to him by bishop for the Arch- an auxiliary following his ects, decisions and diocesan served as auxiliary for four 15 August with preferred pages diocese of Glasgow fol - health scare at the beginning initiatives. years before his appointment names. lowing a request from of the year. With Glasgow embarked on to Paisley in 1988. He will then make a formal 6,7,10,11 Archbishop Philip In an ad clerum letter, sent a wide-ranging review of Although usually chosen submission to the Apostolic out this week, he stated: “I am parish pastoral provision, the from among the diocesan Nuncio who conducts a Tartaglia. -

Scotland ; Picturesque, Historical, Descriptive

250 SCOTLAND DELINEATED. the very name of Macgregor, and rendering the meeting of four of them together at one time a capital crime. Other enactments against them were occasionally renewed, and those proscriptions were in force until the eighteenth century. In 1715 occurred the "Loch Lomond Expedition," against the Macgregors, who, in defiance of the laws against them continued their marauding expeditions under the celebrated Rob Roy Macgregor, and were in reality public robbers. They had seized all the boats on the lake, invaded the island of Inch- Murrin, killed many of the deer belonging to the Duke of Montrose, and committed other excesses. A strong force of volunteers from towns in the counties of Renfrew and Ayr was sent against them to recover the boats, assisted by about one hundred seamen from the ships of war in the Clyde, commanded by seven officers. They sailed up the Leven, and were drawn three miles 4n the course by horses. The contemporary account quaintly states that when " the pinnaces and boats within the mouth of the Loch had spread their sails, and the men on the shore had ranged themselves in order, marching along the side of the Loch for scouring the coast, they made altogether so very fine an appearance as had never been seen in that place before, and might have gratified even a curious person." The Macgregors, however, had disappeared, and the volunteers returned to Dunbarton, after securing the captured booty, without any demonstration of their courage. The Leven is the discharge from Loch Lomond, and traverses the beautiful vale nearly six miles to the Clyde at Dunbarton Castle. -

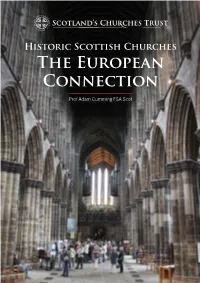

The European Connection

Historic Scottish Churches The European Connection Prof Adam Cumming FSA Scot Adam Cumming Talk “It is often assumed that Scotland took its architectural lead from England, but this is not completely true, Scotland had its own links across Europe, and these developed and changed with time.” cotland has many medieval Glasgow Cathedral which can be churches though not all are shown to have architectural links well known. They deserve across Europe. Sgreater awareness. Many The early Scottish church, that of are ruined but many are not, and Ninian and Columba (as well as many others often survive in some form in others), was part of the early church adapted buildings. before the great schism 1054. It was It is often assumed that Scotland organised a little like the Orthodox took its architectural lead from Churches now. The church below is England, but this is not completely that of Rila Monastery in Bulgaria, an true, Scotland had its own links Orthodox community and similar in across Europe, and these developed plan to early Scottish ones with the and changed with time. The changes church in the centre of the complex. were usually a response to politics It is often described as Celtic and trade. This is of course reflected which is a later description but does in the buildings across Scotland. emphasise a common base with It can be argued that these form a Ireland and Wales etc. There was distinctive part of European culture a great deal of movement across with regional variations. Right is northern Europe and it retained close links with Ireland and elsewhere via ‘Schottenkloster’ and other mission centres. -

Old West Kirk of Greenock 15911591----18981898

The Story of The Old West Kirk Of Greenock 15911591----18981898 by Ninian Hill Greenock James McKelvie & Sons 1898 TO THE MEMORY OF CAPTAIN CHARLES M'BRIDE AND 22 OFFICERS AND MEN OF MY SHIP THE "ATALANTA” OF GREENOCK, 1,693 TONS REGISTER , WHO PERISHED OFF ALSEYA BAY , OREGON , ON THE 17TH NOVEMBER , 1898, WHILE THESE PAGES ARE GOING THROUGH THE PRESS , I DEDICATE THIS VOLUME IN MUCH SORROW , ADMIRATION , AND RESPECT . NINIAN HILL. PREFACE. My object in issuing this volume is to present in a handy form the various matters of interest clustering around the only historic building in our midst, and thereby to endeavour to supply the want, which has sometimes been expressed, of a guide book to the Old West Kirk. In doing so I have not thought it necessary to burden my story with continual references to authorities, but I desire to acknowledge here my indebtedness to the histories of Crawfurd, Weir, and Mr. George Williamson. My heartiest thanks are due to many friends for the assistance and information they have so readily given me, and specially to the Rev. William Wilson, Bailie John Black, Councillor A. J. Black, Captain William Orr, Messrs. James Black, John P. Fyfe, John Jamieson, and Allan Park Paton. NINIAN HILL. 57 Union Street, November, 1898. The Story of The Old West Kirk The Church In a quiet corner at the foot of Nicholson Street, out of sight and mind of the busy throng that passes along the main street of our town, hidden amidst high tenements and warehouses, and overshadowed at times by a great steamship building in the adjoining yard, is to be found the Old West Kirk. -

Modern Alternative Popes*

Modern Alternative Popes* Magnus Lundberg Uppsala University The Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) is arguably the most important event in modern Catholicism, and a major act on the twentieth-century religious scene at large. On several points, the conciliar fathers made changes in how the Catholic Church perceived the modern world. The language in the decrees was different from earlier councils’, and the bishops opened up for ecumenism and interreligious dialogue, seeing at least “seeds of truth” in other religious traditions. The conciliar fathers also voted in favour of liberty of religion, as meaning something more than the right to practise Catholic faith. A very concrete effect of the Council was the introduction of the New Mass Order (Novus Ordo Missae) in 1969 that replaced the traditional Roman rite, decreed by Pius V in 1570. Apart from changes in content, under normal circumstances, the new mass should be read in the vernacular, not in Latin as before. Though many Catholics welcomed the reforms of Vatican II, many did not. In the period just after the end of the Council, large numbers of priests and nuns were laicized, few new priest candidates entered the seminaries, and many laypeople did not recognize the church and the liturgy, which they had grown up with. In the post- conciliar era, there developed several traditionalist groups that criticized the reforms and in particular the introduction of the Novus Ordo. Their criticism could be more or less radical, and more or less activist. Many stayed in their parishes and attended mass there, but remained faithful to traditional forms of devotions and paid much attention to modern Marian apparitions. -

St Machar's Cathedral Transepts

Property in Care (PIC)ID: PIC 265 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90001) Taken into State care: 1911 (Guardianship) Last reviewed: 2014 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE ST MACHAR’S CATHEDRAL TRANSEPTS We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2019 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3/ or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH ST MACHAR'S CATHEDRAL TRANSEPTS SYNOPSIS The property in care comprises the two ruined transepts lying to the east of the roofed nave of Aberdeen (St Machar’s) Cathedral. -

List of Abbots of Dunfermline

LIST OF ABBOTS DUNFERMLINE ABBEY Ebenezer Henderson. Annals of Dunfermline. Glasgow, 1879. From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline By Rev. Peter Chalmers And Biographical Notices or Memoranda of the preceding Abbots. LIST OF ABBOTS DUNFERMLINE ABBEY Ebenezer Henderson. Annals of Dunfermline. Glasgow, 1879. From Historical and Statistical Account Of Dunfermline By Rev. Peter Chalmers Vol. I P.176- In Steven‟s History of the ancient Abbeys, Monasteries, &c. of England, vol. i. fol. 1722, there is a Life of St Benedict, and an account of that order, and its rules, from which it appears that there were connected with the order as members of it, not less than 48 popes from St Boniface IV to Gregory XII inclusive; 11 emperors, who resigned their dignity, and became of the order of St Benedict, from the year 725 to 1039; 9 empresses; 10 queens, one of whom was Maud, Queen of England, grandchild of Malcolm Canmore; 20 kings (besides 11 others, an emperors, who submitted to the rule); 8 princes, sons of do; 15 dukes of Venice, Italy &c.; 13 earls, besides many other persons of different ranks. There are inserted in the column also two bulls in favour of the order, one by Pope Gregory, and the other, its confirmation by Pope Zachary I. 2 The monastery of Dunfermline is generally thought to have been ony a Priory till the reign of David I, and to have been raised by him to the rank of an Abbey, on the occasion of his bringing thirteen monks from Canterbury; which, on the supposition of the previous occupants being Culdees, was intended to reconcile them to the new order of things. -

Life of George Wishart, the Scottish Martyr

: LIFE OF GEORGE WISHART THE SCOTTISH MARTYR WITH HIS TRANSLATION OF THE HELVETIAN CONFESSION AND A GENEALOGICAL HISTORY OF THE FAMILY OF WISHART REV. CHARLES ROGERS, LLD. HISTORIOGRAPHER TO THE ROYAL HISTORICAL SOCIETY, FELLOW OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES OF SCOTLAND, AND CORRESPONDING MEMBER OF THE HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF NEW ENGLAND '•Jltbrary^') EDINBURGH WILLIAM PATERSON, PRINCES STREET 1876 EDINBURGH : PRINTED BY M'FARLANE AND ERSKINE, ST JAMES SQUARE. 4f' nyt^^^cti^.u*^ cctCvMM«<^in i^- ^^%^ ^^yry^""^^ ^it^^^i^^^ <^i4§;w«.-m From the Mayor's Calendar Bristol PREFACE. An inquiry into the life of George Wishart presented few attractions. Believing that he claimed the gift of prophecy, Mr Hill Burton * describes him as " a visionary." Mr Froudef charges him with preaching without authority and with illegally assuming the priestly office. Professor Lorimer| alleges that, in his early ministry, he denied the doctrine of the Atonement. Mr Tytler§ has sought to prove that he intended murder, by conspiring against the life of Cardinal Beaton. Having ventured on the elucidation of his history, I have investigated the charges brought against him, with care and, I trust, impartiality. The result will be found in these pages. Meanwhile I may summarise my deductions, and say that the martyr has, from the inquiry, come forth unstained. He did not claim prophetic powers ; he preached with canonical sanction ; he did not act as a priest or ordained clergyman ; he taught the doctrine of the Atonement through- out his whole ministry ; he did not conspire against Beaton, and if he knew of the conspiracy he condemned it. -

Index of People

Last Name First Name Description of Article Year of Issue Page No Abel Christian Doune school prize-winner 1934 140 Abel Mary (sp Chapin) East Kilmadock Church wedding for Doune woman 1942 69 Abercrombie Catherine Dux of Strathblane School 1959 39 Abercrombie James (sp Newton) Bannockburn soldier weds in Bishop Auckland 1955 78 Abercromby Elizabeth A. (sp Macgregor) August wedding 1967 96 Abercromby Irene (sp McBryde) Ladywell Church wedding 1959 119 Abercromby John Exchange official retires 1968 17 Abercromby Moira (sp Strachan) Erskine-Marykirk wedding 1952 116 Abercromby Thomas S. (sp MacDonald St Ninians Old Parish Church wedding 1960 44 Abernethy Thomas (sp Ensell) Dunblane Hydro wedding 1939 22 Abernethy Margo J. (sp King) Dunblane Cathedral wedding 1965 49 Abernethy Walter M. (sp Yule) Kippen wedding 1968 103 Adam Douglas (Sp Campbell) Callander wedding 1930 28 Adam George BB Award winner 1934 113 Adam George China Merchant, Stirling 1916 27 Adam George Riverside School dux 1932 65 Adam Isabel Doctor weds at Holy Rude 1934 11 Adam Jack (sp Kennedy) Stirling Baptist Church wedding 1939 19 Adam James Cambusbarron minister retires 1930 108 Adam James Denny Show President 1933 163 Adam James (Reverend) Jubilee of Cambusbarron minister 1936 105 Adam James (sp Wilson) Station Hotel wedding for Stirling couple 1939 18 Adam Mary Ann (sp Muirhead) Golden Lion Hotel wedding 1939 18 Adam Thomas Local farmers at ploughing match 1933 123 Adam Thomas St Ninians School dux 1932 65 Adam Thomas Stirling High School scholarship winner 1938 124 Adam -

Clan WISHART

Clan WISHART ARMS Argent, three piles meeting in point Gules CREST A demi eagle with wings expanded Proper MOTTO Mercy is my desire SUPPORTERS Two horses Argent, saddled and bridled Gules Guishard in old French means ‘prudent’ or ‘wise’. The name being descriptive of a personal quality, the identity of the first person to bear it must be largely a matter of conjecture. Nesbit states that Robert, a natural son of David, Earl of Huntington, was a valiant crusader and was known by such an epithet. William Wishard witnessed a grant in favor of the Abbey of Cambuskenneth around 1200. John Wishard was a witness to the marking of the boundaries between the lands of Conon and Tulloch. William Wischard was a monk at St Andrews n 1250. Lands were granted to Adam Wishart of Logie by the Earl of Angus around 1272. The family also acquired the lands of Pitarro. James Wishart of Pitarro was a judge in the reign of James V. His son, George born around 1513, was to become one of the first Protestant martyrs in Scotland. He was educated at the University of Aberdeen and on completing his studies, he traveled in France and Germany. He quickly absorbed the new Protestant theology and when he returned to Scotland he soon found himself at odds with the authorities. He was summoned before the Bishop of Brehin to answer a charge of heresy but he elected to withdraw to England instead. He returned to Scotland in 1543 and began to preach publicly at Montrose and Dundee. He then removed to the west of Scotland, preaching around the town of Ayr.