Athenian Anarchists & Anti-Authoritarians

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\Users\Mark\Documents\RWORKER\Rw Sept-Oct

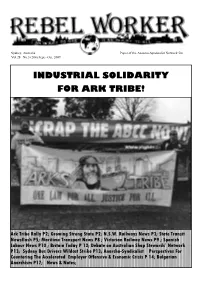

Sydney, Australia Paper of the Anarcho-Syndicalist Network 50c Vol.28 No.3 (204) Sept.- Oct. 2009 INDUSTRIAL SOLIDARITY FOR ARK TRIBE! Ark Tribe Rally P2; Growing Strong State P2; N.S.W. Railways News P3; State Transit Newsflash P5; Maritime Transport News P8 ; Victorian Railway News P9 ; Spanish Labour News P10 ; Britain Today P 12; Debate on Australian Shop Stewards’ Network P13; Sydney Bus Drivers Wildcat Strike P13; Anarcho-Syndicalist Perspectives For Countering The Accelerated Employer Offensive & Economic Crisis P 14; Bulgarian Anarchism P17; News & Notes; 2 Rebel Worker suburbs in Adelaide. 200 people I think, destroying rights for the rest of us. The Rebel Worker is the bi-monthly maybe nearing 300? Judging by us having only time I felt like heckling was “like Paper of the A.S.N. for the propo- given out 50 leaflets to less than a quarter Ned Kelly, he’s been pushed around, gation of anarcho-syndicalism in of the crowd in about 2 minutes.5 political forced to do things he shouldn’t have to..” Australia. forces made an appearance, including the where I was too shy to heckle with “but he greens, democrats, an independent, ‘free still hasn’t shot any cops!” Unless otherwise stated, signed Australia party’(newly formed party of Would have got a laugh or two, especially Articles do not necessarily represent ‘motorcycle enthusiasts’(for anyone inter- from the “motorcycle enthusiasts”. Any- the position of the A.S.N. as a whole. nationally, bikers have been targeted by way.. to my understanding a motion was Any contributions, criticisms, letters absurd state powers recently, and have passed at the ACTU (Australian Council or formed a political party) and Socialist Al- of Trade Unions) (amazingly..) congress, Comments are welcome. -

The May 1968 Archives: a Presentation of the Anti- Technocratic Struggle in May 1968

The May 1968 Archives: A Presentation of the Anti- Technocratic Struggle in May 1968 ANDREW FEENBERG The beginning of the May ’68 events coincided with a United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) conference on Marx. This conference brought together Marx scholars from all over the world to Paris, where they could witness the first stirrings of a revolution while debating the continuing validity of Marx’s work. I recall meeting one of these scholars, a prominent Italian Marxist, in the courtyard of the Sorbonne. He recognized me from my association with Herbert Marcuse, who was also at the UNESCO conference. I expected him to be enthusiastic in his support for the extraordinary movement unfolding around us, but on the contrary, he ridiculed the students. Their movement, he said, was a carnival, not a real revolution. How many serious-minded people of both the left and the right have echoed these sentiments until they have taken on the air of common sense! The May ’68 events, we are supposed to believe, were not real, were a mere pantomime. And worse yet, La pensée ’68 is blamed for much that is wrong with France today. I consider such views of the May ’68 events profoundly wrong. What they ignore is the political content of the movement. This was not just a vastly overblown student prank. I believe the mainstream of the movement had a political conception, one that was perhaps not realistic in terms of power politics, but significant for establishing the horizon of progressive politics since PhaenEx 4, no. -

Though Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

Volume X, Issue 14 uJuly 12, 2012 IN THIS ISSUE: briefs...............................................................................................................1 Crisis in Greece: Anarchists in the Birthplace of Democracy By George papadopoulos .....................................................................................4 From Pakistan to Yemen: Adapting the U.S. Drone Strategy Amir Mokhtar Belmokhtar By Brian Glyn Williams ........................................................................................7 Holier Than Thou: Rival Clerics in the Syrian Jihad By Aron Lund .........................................................................................................9 Terrorism Monitor is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation. The Terrorism Monitor is designed to be read by policy- makers and other specialists yet WAS AL-QAEDA’S SAHARAN AMIR MOKHTAR BELMOKHTAR KILLED IN THE be accessible to the general public. BATTLE FOR GAO? The opinions expressed within are solely those of the authors and do Though al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) continues to deny the death of one not necessarily reflect those of of its leading amirs in the late June battle for the northern Malian city of Gao, the The Jamestown Foundation. movement has yet to provide any evidence of the survival of Mokhtar Belmokhtar (a.k.a. Khalid Abu al-Abbas), the amir of AQIM’s Sahara/Sahel-based al-Mulathamin Unauthorized reproduction Brigade. [1] or redistribution of this or any Jamestown publication is strictly Belmokhtar and his AQIM fighters -

The Evolution of Terrorism in Greece from 1975 to 2009

Research Paper No. 158 Georgia Chantzi (Associate in the International Centre for Black Sea Studies, ICBSS) THE EVOLUTION OF TERRORISM IN GREECE FROM 1975 TO 2009 Copyright: University of Coventry, (Dissertation in the Humanities and Social Science), UK. PS. Mrs. Georgia Chantzi permitted RIEAS to publish her Research Thesis (MA). RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR EUROPEAN AND AMERICAN STUDIES (RIEAS) # 1, Kalavryton Street, Alimos, Athens, 17456, Greece RIEAS URL:http://www.rieas.gr 1 RIEAS MISSION STATEMENT Objective The objective of the Research Institute for European and American Studies (RIEAS) is to promote the understanding of international affairs. Special attention is devoted to transatlantic relations, intelligence studies and terrorism, European integration, international security, Balkan and Mediterranean studies, Russian foreign policy as well as policy making on national and international markets. Activities The Research Institute for European and American Studies seeks to achieve this objective through research, by publishing its research papers on international politics and intelligence studies, organizing seminars, as well as providing analyses via its web site. The Institute maintains a library and documentation center. RIEAS is an institute with an international focus. Young analysts, journalists, military personnel as well as academicians are frequently invited to give lectures and to take part in seminars. RIEAS maintains regular contact with other major research institutes throughout Europe and the United States and, together with similar institutes in Western Europe, Middle East, Russia and Southeast Asia. Status The Research Institute for European and American Studies is a non-profit research institute established under Greek law. RIEAS‟s budget is generated by membership subscriptions, donations from individuals and foundations, as well as from various research projects. -

LONDON Book Fair 2018 Rights List

LONDON Book Fair 2018 Rights List Éditions Calmann-Lévy 21, rue du Montparnasse 75006 Paris FRANCE www.calmann-levy.fr Rights Department Patricia Roussel Rights Director [email protected] +33 (0)1 49 54 36 49 Julia Balcells Foreign & Subsidiary Rights [email protected] +33 (0)1 49 54 36 48 Table of contents Highlights Fiction & Non Fiction • Highlights Fiction Camille Anseaume - Four Walls and a Roof - Quatre murs et un toit •6 Sylvie Baron - Rendezvous in Bélinay - Rendez-vous à Bélinay •7 Boris Bergmann - Apnea - Nage libre •8 Roxane Dambre - An Almost Perfect Karma - Un karma presque parfait •9 Marie-Bernadette Dupuy - Amelia, a Heart in Exile - Amélia, un coeur en exil •10 Johann Guillaud-Bachet - Drowned Alive - Noyé vif •11 Érik L’Homme - Tearing the Shadows - Déchirer les ombres •12 Karine Lambert - Once Upon a Tree - Un arbre, un jour •13 Hélène Legrais - The Angels of Beau-Rivage - Les anges de Beau-Rivage •14 Alfred Lenglet - Hearts of Glass - Coeurs de glace •15 Antonin Malroux- The Straw-made Bread - Le pain de paille •16 Éric Le Nabour - Back to Glenmoran - Retour à Glenmoran •17 Florence Roche - Philomena and her kin - Philomène et les siens •18 Julien Sandrel - The Room of Wonders - La Chambre des merveilles •19 Jean Siccardi - Stepping Stone Inn - L’auberge du Gué •20 Laurence Peyrin - The Virgins’ Wing - L’aile des vierges •21 Pascal Voisine - My Kid - Mon Gamin •22 • Highlights Suspense Fiction Jérôme Loubry - The Hounds of Detroit - Les chiens de Detroit •24 Philippe Lyon -The Black Piece - L’oeuvre noire -

Athens Strikes & Protests Survival Guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the Crisis Day Trip Delphi, the Navel of the World Ski Around Athens Yes You Can!

Hotels Restaurants Cafés Nightlife Sightseeing Events Maps ATHENS Strikes & Protests Survival guide Budget Athens Winter 2011 - 2012 Beat the crisis Day trip Delphi, the Navel of the world Ski around Athens Yes you can! N°21 - €2 inyourpocket.com CONTENTS CONTENTS 3 ESSENTIAL CITY GUIDES Contents The Basics Facts, habits, attitudes 6 History A few thousand years in two pages 10 Districts of Athens Be seen in the right places 12 Budget Athens What crisis? 14 Strikes & Protests A survival guide 15 Day trip Antique shop Spend a day at the Navel of the world 16 Dining & Nightlife Ski time Restaurants Best resorts around Athens 17 How to avoid eating like a ‘tourist’ 23 Cafés Where to stay Join the ‘frappé’ nation 28 5* or hostels, the best is here for you 18 Nightlife One of the main reasons you’re here! 30 Gay Athens 34 Sightseeing Monuments and Archaeological Sites 36 Acropolis Museum 40 Museums 42 Historic Buildings 46 Getting Around Airplanes, boats and trains 49 Shopping 53 Directory 56 Maps & Index Metro map 59 City map 60 Index 66 A pleasant but rare Athenian view athens.inyourpocket.com Winter 2011 - 2012 4 FOREWORD ARRIVING IN ATHENS he financial avalanche that started two years ago Tfrom Greece and has now spread all over Europe, Europe In Your Pocket has left the country and its citizens on their knees. The population has already gone through the stages of denial and anger and is slowly coming to terms with the idea that their life is never going to be the same again. -

Daniel Theodor Danielsen

Across Oceans, Across Time ® … Stories from the Family History & Genealogy Center … Daniel Theodore Danielsen was born on November 8, 1842 in Næstved to carpenter Niels Christian Danielsen and his wife, Johanne Kirstine Andersen. At the age of one his family moved to Copenhagen, locating near Rosenborg Castle. In later years Daniel recounted that his childhood playmates included two children of Christian IX, George – later King George I of Greece – and Alexandra, who became the wife of the future Edward VII of England. In April 1865 Daniel left his homeland for the U.S. After clerking in a grocery store in Chicago he worked his way eastward for two years, intending to return to Denmark and settle down. Upon hearing, however, that there was a need for immigrant labor in the South, he decided to investigate, and found employment at a sawmill in Edgefield (now Saluda) Co., where he settled and spent the rest of his life. In 1870 he married P. Bethany Salter, with whom he had six children: Christian, August, Johanna, Christina, Elizabeth, and John. After his first wife’s death, he married Mrs. Mary Elizabeth Davenport and Effie Wilson. The former playmate of royalty, immigrant Daniel integrated well into his new life in the post-bellum South. He became a member of the Sardis Baptist Church in 1872, later moving his membership to the West End Baptist Church in Newberry, where he served in several official capacities. He was also a member of several fraternal organizations. He farmed and was employed at several sawmills, including the Newberry Cotton Mill, where he was night watchman for 28 years until his death in 1916. -

Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature

i “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair Professor Naomi Seidman Professor Nathaniel Deutsch Professor Juana María Rodríguez Summer 2016 ii “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature Copyright © 2016 by Anna Elena Torres 1 Abstract “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature by Anna Elena Torres Joint Doctor of Philosophy with the Graduate Theological Union in Jewish Studies and the Designated Emphasis in Women, Gender and Sexuality University of California, Berkeley Professor Chana Kronfeld, Chair “Any Minute Now the World’s Overflowing Its Border”: Anarchist Modernism and Yiddish Literature examines the intertwined worlds of Yiddish modernist writing and anarchist politics and culture. Bringing together original historical research on the radical press and close readings of Yiddish avant-garde poetry by Moyshe-Leyb Halpern, Peretz Markish, Yankev Glatshteyn, and others, I show that the development of anarchist modernism was both a transnational literary trend and a complex worldview. My research draws from hitherto unread material in international archives to document the world of the Yiddish anarchist press and assess the scope of its literary influence. The dissertation’s theoretical framework is informed by diaspora studies, gender studies, and translation theory, to which I introduce anarchist diasporism as a new term. -

The Case of Athens

Uniconflicts 61 05 Crisis ridden space, knowledge production and social struggles: The case of Athens Stefania Gyftopoulou PhD Candidate in Geography, Harokopio University e-mail: [email protected] Asimina Paraskevopoulou PhD Candidate in Development Planning, University College London e-mail: [email protected] 1. CRISIS 1.1. ‘Crisis’ as critique and knowledge The word, ‘crisis’ comes from the Greek verb ‘Krinein’ which means to judge, to form an opinion, to criticize. Crisis does not predefine a specific response. It is the act and the outcome of the critique; the mental act that leads to a response. Accordingly, cri- tique comes from the Greek noun ‘kritiki’. ‘Kritiki’ is carried out in order for ‘krinein’ to take place. Thus, crisis cannot truly exist without the act of critique. Roitman (2011: para 6) provides an enlightening explanation of “how crisis is constructed as an object of knowledge”. It is a 62 Crisis ridden space means to think of history as a narrative of events, politics, culture, relationships and even individual behaviours and norms. It works as a means to judge the past and learn from the past. But when she speaks of judging the past, is she not referring to the act of critique? Foucault asks for a critique that does not plainly evalu- ate whether the object is good or bad, correct or wrong. He speaks of a critique as a practice, producing along this process, different realities - values and truths - hence, a new ‘normalcy’. Thus, crisis is about becoming. 1.2. Crisis as subject formation and governmentality Through the production of ‘truths’ and ‘normalcy’ crisis influenc- es our understanding not only of ourselves but also of the posi- tion we hold in our societies. -

Airburshed from History?

8May68_Template.qxd 07/06/2018 10:12 Page 88 Airbrushed As the May 68 media and nostalgia machines got under way, occasional from history? references were made to the UK’s student revolt and its organisation RSSF, the Revolutionary Socialist Students A Note on RSSF Federation. This Note draws together a & May 68 varied assortment of sources to assess what is known about what happened, suggesting that the British student rebellion of the 1968 period has largely been airbrushed out of modern history as ephemeral and implicitly Ruth Watson a minor British copycat phenomenon in & Greg Anscombe comparison to French, German and Italian and other European movements, and, of course, the various movements in the Unite States. The impressive scale of recent student support for the campaign against the reduction of comprehensive pensions for university teachers is a reminder that, as a body, students have had, and can have a distinct role in progressive politics, nothwithstanding the careerism and elitism which has characterised official National Union of Student (NUS) associated politics at various — too many — periods. Remember the long marches Mature reflections after 50 years have their value, but one thematic ingredient, if not an actual material outcome — a piece of real history making — must be the long marches through the institutions taken by many from that generation of students. While there are many who have travelled outside the red lines of left activism and socialism, it is arguable that the collective march has sustained and enriched subsequent political life. It was, in this 8May68_Template.qxd 07/06/2018 10:12 Page 89 Airbrushed from history? 89 sense, not just student ferment and unrest: it was a rebellion, with honourable echoes in history and notable advances of ideology. -

Cesifo Working Paper No. 3789 Category 2: Public Choice April 2012

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Brockhoff, Sarah; Krieger, Tim; Meierrieks, Daniel Working Paper Looking back on anger: Explaining the social origins of left-wing and nationalist-separatist terrorism in Western Europe, 1970-2007 CESifo Working Paper, No. 3789 Provided in Cooperation with: Ifo Institute – Leibniz Institute for Economic Research at the University of Munich Suggested Citation: Brockhoff, Sarah; Krieger, Tim; Meierrieks, Daniel (2012) : Looking back on anger: Explaining the social origins of left-wing and nationalist-separatist terrorism in Western Europe, 1970-2007, CESifo Working Paper, No. 3789, Center for Economic Studies and ifo Institute (CESifo), Munich This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/57943 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. may exercise further usage rights as specified in the indicated licence. -

Balkan Wars Between the Lines: Violence and Civilians in Macedonia, 1912-1918

ABSTRACT Title of Document: BALKAN WARS BETWEEN THE LINES: VIOLENCE AND CIVILIANS IN MACEDONIA, 1912-1918 Stefan Sotiris Papaioannou, Ph.D., 2012 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe, Department of History This dissertation challenges the widely held view that there is something morbidly distinctive about violence in the Balkans. It subjects this notion to scrutiny by examining how inhabitants of the embattled region of Macedonia endured a particularly violent set of events: the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War. Making use of a variety of sources including archives located in the three countries that today share the region of Macedonia, the study reveals that members of this majority-Orthodox Christian civilian population were not inclined to perpetrate wartime violence against one another. Though they often identified with rival national camps, inhabitants of Macedonia were typically willing neither to kill their neighbors nor to die over those differences. They preferred to pursue priorities they considered more important, including economic advancement, education, and security of their properties, all of which were likely to be undermined by internecine violence. National armies from Balkan countries then adjacent to geographic Macedonia (Bulgaria, Greece, and Serbia) and their associated paramilitary forces were instead the perpetrators of violence against civilians. In these violent activities they were joined by armies from Western and Central Europe during the First World War. Contrary to existing military and diplomatic histories that emphasize continuities between the Balkan Wars of 1912-1913 and the First World War, this primarily social history reveals that the nature of abuses committed against civilians changed rapidly during this six-year period.