Mensch Speech Final P PDF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East

Istanbul Papers Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East: A Transatlantic Strategy for Partnership The Istanbul Papers were presented at: Istanbul Paper #1 The Atlantic Alliance at a New Crossroads Istanbul, Turkey A conference of: June 25 – 27, 2004 TURKıSH ECONOMıC AND SOCıAL STUDıES FOUNDATıON Core sponsorship: Additional support from: The German Marshall Fund TESEV TURKıSH ECONOMıC AND of the United States Bankalar Cad. No:2 K:3 SOCıAL STUDıES 1744 R Street, NW 34420 Karaküy/Istanbul FOUNDATıON Washington, DC 20009 T 212 292 89 03 T 1 202 745 3950 F 212 292 90 45 F 1 202 265 1662 W www.tesev.org.tr E [email protected] W www.gmfus.org Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East: A Transatlantic Strategy for Partnership Istanbul Paper #1 i ii Authors* Urban Ahlin, Member of the Swedish Parliament Mensur Akgün, Turkish Economic and Social Science Studies Foundation Gustavo de Aristegui, Member of the Spanish Parliament Ronald D. Asmus, The German Marshall Fund of the United States Daniel Byman, Georgetown University Larry Diamond, Hoover Institution Steven Everts, Centre for European Reform Ralf Fücks, Heinrich Böll Foundation Iris Glosemeyer, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik Jana Hybaskova, Czech Member of the European Parliament Thorsten Klassen, The German Marshall Fund of the United States Mark Leonard, Foreign Policy Centre Michael McFaul, Stanford University Thomas O. Melia, Georgetown University Michael Mertes, Dimap Consult Joshua Muravchik, American Enterprise Institute Kenneth M. Pollack, The Brookings Institution Karen Volker, Office of Senator Joe Lieberman Jennifer Windsor, Freedom House * The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the authors’ affiliation. -

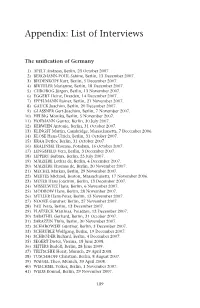

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

The Jewish Contribution to the European Integration Project

The Jewish Contribution to the European Integration Project Centre for the Study of European Politics and Society Ben-Gurion University of the Negev May 7 2013 CONTENTS Welcoming Remarks………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Dr. Sharon Pardo, Director Centre for the Study of European Politics and Society, Jean Monnet National Centre of Excellence at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Walther Rathenau, Foreign Minister of Germany during the Weimar Republic and the Promotion of European Integration…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Dr. Hubertus von Morr, Ambassador (ret), Lecturer in International Law and Political Science, Bonn University Fritz Bauer's Contribution to the Re-establishment of the Rule of Law, a Democratic State, and the Promotion of European Integration …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Mr. Franco Burgio, Programme Coordinator European Commission, Brussels Rising from the Ashes: the Shoah and the European Integration Project…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Mr. Michael Mertes, Director Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Israel Contributions of 'Sefarad' to Europe………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………21 Ambassador Alvaro Albacete, Envoy of the Spanish Government for Relations with the Jewish Community and Jewish Organisations The Cultural Dimension of Jewish European Identity………………………………………………………………………………….…26 Dr. Dov Maimon, Jewish People Policy Institute, Israel Anti-Semitism from a European Union Institutional Perspective………………………………………………………………34 -

Alois Mertes

ALOIS MERTES WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN Dr. Alois Mertes (1921–1985) war einer der profiliertestenaußenpolitischenDenkerundein bedeutenderVertreterdespolitischenKatholizis- HANNSJürgENKüStErS(HrSg.) musinderBundesrepublikDeutschland.Von 1952angehörteerdemAuswärtigenDienstder BundesrepublikDeutschlandan.Derprofunde KennerdersowjetischenAußen-undSicherheits- politikavanciertezudemzumaußenpolitischen Ratgeber der Unionsparteien. DieKonrad-Adenauer-Stiftunge.V.erinnerte am7.November2012miteinerVeranstaltung imWeltsaaldesAuswärtigenAmtesinBonn andiesenüberzeugtenEuropäerundPatrioten. DervorliegendeBandfasstdieimVerlaufder PräsentationgehaltenenAnsprachenzusammen. www.kas.de ALOIS MERTES – WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN REDEBEITRÄGE ANLÄSSLICH DER VERANSTALTUNG AM 7. NOVEMBER 2012 IM WELTSAAL DES AUSWÄRTIGEN AMTES IN BONN ALOIS MERTES – WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN REDEBEITRÄGE ANLÄSSLICH DER VERANSTALTUNG AM 7. NOVEMBER 2012 IM WELTSAAL DES AUSWÄRTIGEN AMTES IN BONN HANNS JÜRGEN KÜSTERS (HRSG.) © 2013, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. www.kas.de Gestaltung: SWITSCH Kommunikationsdesign, Köln Umschlagfoto: Alois Mertes im -

The Memory of the Century

Institut für Spring 2001 die Wissenschaften vom Menschen Institute for Human Sciences A-1090 Wien Spittelauer Lände 3 Tel. (+431) 313 58-0 Fax (+431) 313 58-30 CONFERENCE The IWM’s first major conference of the year took place March [email protected] www.iwm.at 9th through the 11th at the Palais Ferstel in central Vienna. Scholars and public figures from around the world gathered to discuss the problem of historical memory, a problem that has moved into the center of political, social, and cultural debates in Contents many countries as they reflect upon the recent past. 9 Workshop Citizenship and Identity The Memory of the Century 11 Kolloquium Offene Seele – Harmonische Welt FRENCH PHILOSOPHER Paul Ricoeur opened the conference 12 Conference on Friday evening, March 9th with a public lecture on the When Globalization Fails... relation between memory and history. As in his main work, Temps et Récit, Ricoeur’s arguments in this keynote speech 15 Seminar with Slavenka Drakulic revolved around the presence of the absent in our imagina- The Politics of Truth and Justice tion, which he identified as the main problem of epistemo- logical and chronological reflection and hence of philoso- 25 Notes on Books phy and history in general. According to Ricoeur, the inter- Charles Taylor on Multiple secting lines of “actual presentation” and “representation of Modernities the past” constitute a riddle in the phenomenon of Sorin Antohi on Ioan Petru Culianu memory with respect to the question of truth. The talk’s three parts considered memory as the fundamental matrix, 26 Guest Contributions the external object, and the informed product of history, Michel Serres and Pierre Nora and addressed the paradoxes that result from these differ- on Memory ent functions. -

Grußwort JCPA-Europakonferenz P

Greetings to the Participants of the JCPA/KAS Israel Conference “Europe an Israel: A New Paradigm” by Michael Mertes, Director of KAS Israel Jerusalem, March 24th, 2014 On behalf of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, I warmly welcome you to this very topical conference. I would also like to thank our tried-and-tested partner, the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, for the excellent cooperation in preparing today’s event. The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung is a German political foundation dedicated to national as well as international think-tank work and dialogue. We are active around the globe with some 80 offices reaching out to more than 120 countries, and we have been working in Israel for more than 30 years. Let me just say a couple of words about the stake my organization has in this joint conference. Most importantly, it’s the legacy of Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. He was also one of the founding fathers of what is now the European Union. The friendship between him and David Ben-Gurion laid the foundation for the friendship uniting Germany and Israel today. We take great pride in bearing Konrad Adenauer’s name. We also take pride in carrying on the legacy of German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard, under whose leadership (and that of Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol) diplomatic relations between Germany and Israel were established in 1965, almost 50 years ago. Today’s successor of Adenauer and Erhard, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, is a member of our foundation’s board. We fully support her clear stance on Israel: Germany will never be neutral on Israel, and Israel can be sure of German support when it comes to ensuring its security. -

Lloyd George Street 6 P. O. Box 8348 Jerusalem 91082 Israel Phone +

MICHAEL MERTES Lloyd George Street 6 RESIDENT REPRESENTATIVE TO ISRAEL P. O. Box 8348 KONRAD -ADENAUER -STIFTUNG Jerusalem 91082 Israel Phone +972-2-567 18 30 Fax +972-2-567 18 31 June 2012 CURRICULUM VITAE Born 26 March 1953 in Bonn Childhood (1955-1966) in Marseille, Paris and Moscow Married to Barbara Rembser-Mertes (mathematics and physics teacher) Four children (1980, 1984, 1987, 1990) Education 1972 Graduation from high school (Abitur, classical languages): Aloisiuskolleg, Bonn 1972-1974 Military service, reserve officer training 1974-1980 Law studies at Bonn and Tübingen Universities and at the London School of Economics and Political Science (with a focus on Public International Law, Philosophy of Law, Philosophy of Science) Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung scholarship (1975-1980) 1981/83 First/Second State Examination in Law Career 1981 Parliamentary Assistant to Carl Otto Lenz MP 1984 Federal Ministry of Defense: Counsellor, Contracts Department at the Federal Office of Defense Technology and Procurement 1984-1985 Federal Chancellery: Counsellor, Personnel Section 1985-1986 Federal Chancellery: Deputy Head, Cultural and State-Church Affairs Section 1986-1987 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety: Bureau Chief, Minister’s Office 1987-1993 Federal Chancellery: Head, Speech Writing Section 1993-1995 Federal Chancellery: Director, Policy Planning 1995-1998 Federal Chancellery: Director-General, Policy Planning and Cultural Affairs 1998 Interim retirement after change of government 1998-2002 Weekly “Rheinischer -

Mertes 02/09 Q

ESSAYS Ein „deutsches Europa“ Nachruf auf ein Schreckgespenst von Michael Mertes mühen der Bundesregierung, Nach- m 13. Februar 1990 rief barn und Partner davon zu überzeu- der damalige Bundesaußen- gen, das vereinte Deutschland werde Aminister Hans-Dietrich Gen- keine hegemonialen Absichten ver- scher vor den Teilnehmern der „Open folgen, sondern sich harmonisch in Skies“-Konferenz in Ottawa aus: „Ich seine europäische Umgebung ein- bekräftige, was Thomas Mann schon fügen, ja geradezu – in den Worten 1952 erklärte:Wir wollen ein europäi- des ehemaligen Bundeskanzlers Hel- sches Deutschland, nicht ein deut- mut Kohl – „ein Gewinn für das im- sches Europa.“1 Manns Hinweis auf mer mehr zusammenwachsende Eu- die „Furcht anderer Völker vor ropa sein“.4 Deutschland und vor hegemonialen Bereits Ende Oktober 1989, also Plänen, die seine vitale Tüchtigkeit noch vor dem Fall der Mauer, war in ihm eingeben mag“, hatte nach dem Bonner Amtsstuben ein Beitrag in der Fall der Mauer neue Aktualität er- Londoner Times aus der Feder von langt. Seine Absage an ein „deutsches Conor Cruise O’Brien5 wie eine Europa“, verbunden mit dem Be- Bombe eingeschlagen.Der Autor – ein kenntnis zu einem „europäischen angesehener Historiker, einst irischer Deutschland“, avancierte deshalb Diplomat und dann Mitarbeiter des zum Mantra2 der Bonner politischen früheren UN-Generalsekretärs Dag Rhetorik im Jahr der deutschen Ein- Hammarskjöld – wandte sich pole- heit. Sie wurde, wie Timothy Garton misch gegen die positive Stellungnah- Ash später mit leisem Spott notierte, me des damaligen amerikanischen „immer wieder,wie ein Segen oder ein Präsidenten George Bush zur Per- Gebet, zur Geburt des vereinten spektive einer deutschen Einheit und Deutschland intoniert“.3 warnte eindringlich vor der Geburt Den Bonner Akteuren war in der eines „Vierten Reiches“. -

Academy 2007

ZEI Academy in Comparative Regional Integration, 9 - 22 September 2007 ZEI Academy in Comparative Regional Integration 2007 Participants from Africa with Prof. Dr. Hans-Gert Pöttering, Participants, Ruth Hieronymi (MEP), President of the European Parliament Prof. Dr. Matthias Winiger (Rector of Bonn University) and Prof. Dr. Ludger Kühnhardt (ZEI-Director) Lectures, Workshops, Group and Panel Discussions, Simulation Politics Economics Law The Current State of the European Union Economic Principles of Regional The European Union as a Community Prof. Dr. Hans-Gert Pöttering, MEP, Integration of Values President of the European Parliament Prof. Dr. Simona Beretta, ASERI, Dr. Thilo Rensmann, University of Bonn Ruth Hieronymi, Member of the Catholic University Milan European Parliament (MEP-EPP), The Primacy Matter – National vs. Brussels Regional Asymmetries and Protectionist European Law Pressures Prof. Dr. Andreas Haratsch, University The Role of Regions in European Prof. Dr. Simona Beretta of Distant Learning, Hagen Integration Michael Mertes, State Secretary for Managing a Common Currency Acquis Communautaire and the Federal and European Affairs, North Prof. Dr. Simona Beretta Common Market Rhine-Westphalia, Düsseldorf Karlis Svikis, ZEI Winners and Losers of Regional Hans H. Stein, Representative of the Integration Acquis Communautaire and National State of North Rhine-Westphalia in Prof. Dr. Simona Beretta Law Brussels Karlis Svikis, ZEI Measuring Regional Integration The European Parliament in EU Prof. Dr. Philippe de Lombaerde, Acquis -

Israel As a Jewish and Democratic State

3|2012 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 21 Israel as a JewIsh and democratIc state an old Issue Becomes a new challenge Michael Mertes / Christiane Reves The Declaration of Independence of 14 May 1948 defines Israel as a “Jewish State” established in the “Land of Israel” (Eretz Israel). Although the new State is not expressly described as “democratic”, its charter specifies that Israel will ensure “complete equality of social and political rights to all its inhabitants irrespective of religion, race or sex”. It also appeals to the “Arab inhabitants of the State of Israel to participate in the upbuilding of the State on the Michael Mertes is Resi- basis of full and equal citizenship and due representation dent Representative of the Konrad-Adenauer- in all its provisional and permanent institutions”. An Israeli Stiftung in Jerusalem. constitution was to be adopted by an elected Constituent Assembly “not later than 1st October 1948”. A written constitution as envisaged in 1948 does not yet exist, at least not in the form of a coherent document. The Constituent Assembly failed to adopt a constitution in 1949, not least because of disagreement over whether the State of Israel should be a secular democratic state, or one based on the principles of the Halacha.1 Over time, several “Basic Dr. Christiane Reves is a member of the Laws” were adopted which, together with the principles Center for Austrian and laid out in the Declaration of Independence, established German Studies at the state practices and adjudications by the Supreme Court, Ben Gurion University in Be’er Sheva. coalesced into a kind of unwritten constitution.2 1 | Halacha is used to describe Jewish law with all its traditional oral and written commandments and rules. -

ECOWAS-ZEI Academy in Comparative Regional Integration, 16 – 27 March 2009

ECOWAS-ZEI Academy in Comparative Regional Integration, 16 – 27 March 2009 ECOWAS ZEI Academy in Comparative Regional Simulating EU Negotiations Integration 2009 Matthias Vogl (ZEI Program Coordinator) with Dr. Jonas Participants, Alexander Count Lambsdorff (MEP), Prof. Hemou (Director External Relations ECOWAS Commission), Dr. Matthias Winiger (Rector of Bonn University), Monika Dr. Abdel Dansoko (ECOWAS Parliament) and Dr. Daouda Pottgiesser (GTZ Program Coordinator), Prof. Dr. Paul Fall (ECOWAS Court of Justice) Vlek (Director ZEF) and Prof. Dr. Ludger Kühnhardt (Director ZEI) Lectures, Workshops, Excursions, Group and Panel Discussions, Simulation Politics Economics Law The Current Situation in the European Regional Asymmetries and Protectionist The Primacy of Law – National vs. Union Pressures European Law Alexander Count Lambsdorff, Member of Prof. Dr. Simona Beretta, ASERI, Prof. Dr. Andreas Haratsch, University European Parliament (MEP-Group of the Catholic University Milan of Distant Learning of Hagen Alliance of Liberals and Democrats in Europe) Winners and Losers of Integration: The Current State of Affairs of the Exchanging experiences Prof. Dr. ECOWAS Court of Justice Dr. Daouda The Role of Regions in the European Simona Beretta Fall – Director of Research and Union Michael Mertes, State Secretary, Documentation, ECOWAS Court of Ministry for Federal and European Managing a Common Currency – The Justice Affairs, North Rhine-Westphalia EURO Experience and the ECOWAS Perspective Challenges of EC Competition Law Hans H. Stein, Representative of the Prof. Dr. Simona Beretta Robert Klotz, Hunton & Williams LLP, State of North Rhine-Westphalia in Brussels Brussels Regional Integration in Africa: Assessing the Experiencing of Bi- Acquis Communautaire and the Regional Trade Negotiations Petra Common Market Multilevel Governance: The European Pongracz, German Development Karlis Svikis, ZEI Experience Prof. -

Annual Report 2008

Rep_2008_txtN3.qxp 1/3/2010 2:06 PM Page 1 ANNUAL REPORT OF THE MOSCOW SCHOOL OF POLITICAL STUDIES 2008 (Sixteenth Academic Year) Rep_2008_txtN3.qxp 1/3/2010 2:06 PM Page 2 To the Staff and Alumni of the Moscow School of Political Studies Dear Friends, I congratulate you all on the 10th anniversary of the Moscow School of Polit- ical Studies. The School is well known in Russia and abroad for its active work in pro- moting civil society, and as a forum which brings together young politicians, journalists and businessmen from the very varied regions of Russia. Here in the School these young people have the opportunity to listen to world class experts, and to engage in free-ranging discussion with them about the most pressing problems of political and economic life. All who participate in the School's programmes acquire not only knowledge, but new and reliable friends as well. Today, the School is a centre for mutual enlightenment, for strengthening the values of democracy and public service, for nourishing respect for the law, and for developing new ideas. I wish the staff and alumni of the School the best of health and prosperity, and I look forward to the further successful development of the School itself. President of the Russian Federation Vladimir Putin 31st October, 2003 Page 2 ANNUAL REPORT Rep_2008_txtN3.qxp 1/3/2010 2:07 PM Page 3 Letter from Russian President Vladimir Putin to the staff and alumni of the Moscow School of Political Studies on the occasion of the Tenth anniversary of the founding of the School.