Disc Cussio on Pl Latfo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East

Istanbul Papers Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East: A Transatlantic Strategy for Partnership The Istanbul Papers were presented at: Istanbul Paper #1 The Atlantic Alliance at a New Crossroads Istanbul, Turkey A conference of: June 25 – 27, 2004 TURKıSH ECONOMıC AND SOCıAL STUDıES FOUNDATıON Core sponsorship: Additional support from: The German Marshall Fund TESEV TURKıSH ECONOMıC AND of the United States Bankalar Cad. No:2 K:3 SOCıAL STUDıES 1744 R Street, NW 34420 Karaküy/Istanbul FOUNDATıON Washington, DC 20009 T 212 292 89 03 T 1 202 745 3950 F 212 292 90 45 F 1 202 265 1662 W www.tesev.org.tr E [email protected] W www.gmfus.org Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East: A Transatlantic Strategy for Partnership Istanbul Paper #1 i ii Authors* Urban Ahlin, Member of the Swedish Parliament Mensur Akgün, Turkish Economic and Social Science Studies Foundation Gustavo de Aristegui, Member of the Spanish Parliament Ronald D. Asmus, The German Marshall Fund of the United States Daniel Byman, Georgetown University Larry Diamond, Hoover Institution Steven Everts, Centre for European Reform Ralf Fücks, Heinrich Böll Foundation Iris Glosemeyer, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik Jana Hybaskova, Czech Member of the European Parliament Thorsten Klassen, The German Marshall Fund of the United States Mark Leonard, Foreign Policy Centre Michael McFaul, Stanford University Thomas O. Melia, Georgetown University Michael Mertes, Dimap Consult Joshua Muravchik, American Enterprise Institute Kenneth M. Pollack, The Brookings Institution Karen Volker, Office of Senator Joe Lieberman Jennifer Windsor, Freedom House * The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the authors’ affiliation. -

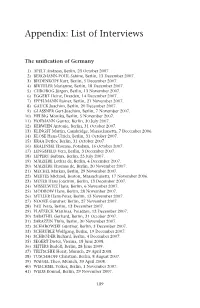

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

The Jewish Contribution to the European Integration Project

The Jewish Contribution to the European Integration Project Centre for the Study of European Politics and Society Ben-Gurion University of the Negev May 7 2013 CONTENTS Welcoming Remarks………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Dr. Sharon Pardo, Director Centre for the Study of European Politics and Society, Jean Monnet National Centre of Excellence at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Walther Rathenau, Foreign Minister of Germany during the Weimar Republic and the Promotion of European Integration…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Dr. Hubertus von Morr, Ambassador (ret), Lecturer in International Law and Political Science, Bonn University Fritz Bauer's Contribution to the Re-establishment of the Rule of Law, a Democratic State, and the Promotion of European Integration …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Mr. Franco Burgio, Programme Coordinator European Commission, Brussels Rising from the Ashes: the Shoah and the European Integration Project…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Mr. Michael Mertes, Director Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Israel Contributions of 'Sefarad' to Europe………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………21 Ambassador Alvaro Albacete, Envoy of the Spanish Government for Relations with the Jewish Community and Jewish Organisations The Cultural Dimension of Jewish European Identity………………………………………………………………………………….…26 Dr. Dov Maimon, Jewish People Policy Institute, Israel Anti-Semitism from a European Union Institutional Perspective………………………………………………………………34 -

View / Open Final Thesis-Hauth Q

HOW MIGRATION HAS CONTRIBUTED THE RISE OF THE FAR-RIGHT IN GERMANY by QUINNE HAUTH A THESIS Presented to the Department of International Studies and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2019 An Abstract of the Thesis of Quinne Hauth for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in the Department of International Studies to be taken June 2019 Title: How Migration Has Contributed to the Rise of the Far-Right in Germany Approved: _______________________________________ Angela Joya Increased migration into Europe in the summer of 2015 signified a shift in how the European Union responds to migration, and now more so than in Germany, which has opened its doors to about 1.5 million migrants as of 2018. While Chancellor Angela Merkel’s welcome helped alleviate the burden placed on countries that bordered the east as well as the Mediterranean, it has been the subject of a lot of controversy over the last three years within Germany itself. Drawing on this controversy, this study explores how migration has affected Germany’s migration policies, and the extent to which it has affected a shift towards the right within the government. I conclude that Germany’s relationship with migration has been complicated since its genesis, and that ultimately Merkel’s welcome was the exception to decades of policy, not the rule. Thus, as tensions increase between migrants and citizens, and policy fails to adapt to benefit both parties, Germany’s politicians will advocate to close the state from migrants more and more. -

Alois Mertes

ALOIS MERTES WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN Dr. Alois Mertes (1921–1985) war einer der profiliertestenaußenpolitischenDenkerundein bedeutenderVertreterdespolitischenKatholizis- HANNSJürgENKüStErS(HrSg.) musinderBundesrepublikDeutschland.Von 1952angehörteerdemAuswärtigenDienstder BundesrepublikDeutschlandan.Derprofunde KennerdersowjetischenAußen-undSicherheits- politikavanciertezudemzumaußenpolitischen Ratgeber der Unionsparteien. DieKonrad-Adenauer-Stiftunge.V.erinnerte am7.November2012miteinerVeranstaltung imWeltsaaldesAuswärtigenAmtesinBonn andiesenüberzeugtenEuropäerundPatrioten. DervorliegendeBandfasstdieimVerlaufder PräsentationgehaltenenAnsprachenzusammen. www.kas.de ALOIS MERTES – WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN REDEBEITRÄGE ANLÄSSLICH DER VERANSTALTUNG AM 7. NOVEMBER 2012 IM WELTSAAL DES AUSWÄRTIGEN AMTES IN BONN ALOIS MERTES – WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN REDEBEITRÄGE ANLÄSSLICH DER VERANSTALTUNG AM 7. NOVEMBER 2012 IM WELTSAAL DES AUSWÄRTIGEN AMTES IN BONN HANNS JÜRGEN KÜSTERS (HRSG.) © 2013, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. www.kas.de Gestaltung: SWITSCH Kommunikationsdesign, Köln Umschlagfoto: Alois Mertes im -

The Memory of the Century

Institut für Spring 2001 die Wissenschaften vom Menschen Institute for Human Sciences A-1090 Wien Spittelauer Lände 3 Tel. (+431) 313 58-0 Fax (+431) 313 58-30 CONFERENCE The IWM’s first major conference of the year took place March [email protected] www.iwm.at 9th through the 11th at the Palais Ferstel in central Vienna. Scholars and public figures from around the world gathered to discuss the problem of historical memory, a problem that has moved into the center of political, social, and cultural debates in Contents many countries as they reflect upon the recent past. 9 Workshop Citizenship and Identity The Memory of the Century 11 Kolloquium Offene Seele – Harmonische Welt FRENCH PHILOSOPHER Paul Ricoeur opened the conference 12 Conference on Friday evening, March 9th with a public lecture on the When Globalization Fails... relation between memory and history. As in his main work, Temps et Récit, Ricoeur’s arguments in this keynote speech 15 Seminar with Slavenka Drakulic revolved around the presence of the absent in our imagina- The Politics of Truth and Justice tion, which he identified as the main problem of epistemo- logical and chronological reflection and hence of philoso- 25 Notes on Books phy and history in general. According to Ricoeur, the inter- Charles Taylor on Multiple secting lines of “actual presentation” and “representation of Modernities the past” constitute a riddle in the phenomenon of Sorin Antohi on Ioan Petru Culianu memory with respect to the question of truth. The talk’s three parts considered memory as the fundamental matrix, 26 Guest Contributions the external object, and the informed product of history, Michel Serres and Pierre Nora and addressed the paradoxes that result from these differ- on Memory ent functions. -

Grußwort JCPA-Europakonferenz P

Greetings to the Participants of the JCPA/KAS Israel Conference “Europe an Israel: A New Paradigm” by Michael Mertes, Director of KAS Israel Jerusalem, March 24th, 2014 On behalf of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, I warmly welcome you to this very topical conference. I would also like to thank our tried-and-tested partner, the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, for the excellent cooperation in preparing today’s event. The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung is a German political foundation dedicated to national as well as international think-tank work and dialogue. We are active around the globe with some 80 offices reaching out to more than 120 countries, and we have been working in Israel for more than 30 years. Let me just say a couple of words about the stake my organization has in this joint conference. Most importantly, it’s the legacy of Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. He was also one of the founding fathers of what is now the European Union. The friendship between him and David Ben-Gurion laid the foundation for the friendship uniting Germany and Israel today. We take great pride in bearing Konrad Adenauer’s name. We also take pride in carrying on the legacy of German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard, under whose leadership (and that of Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol) diplomatic relations between Germany and Israel were established in 1965, almost 50 years ago. Today’s successor of Adenauer and Erhard, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, is a member of our foundation’s board. We fully support her clear stance on Israel: Germany will never be neutral on Israel, and Israel can be sure of German support when it comes to ensuring its security. -

Lloyd George Street 6 P. O. Box 8348 Jerusalem 91082 Israel Phone +

MICHAEL MERTES Lloyd George Street 6 RESIDENT REPRESENTATIVE TO ISRAEL P. O. Box 8348 KONRAD -ADENAUER -STIFTUNG Jerusalem 91082 Israel Phone +972-2-567 18 30 Fax +972-2-567 18 31 June 2012 CURRICULUM VITAE Born 26 March 1953 in Bonn Childhood (1955-1966) in Marseille, Paris and Moscow Married to Barbara Rembser-Mertes (mathematics and physics teacher) Four children (1980, 1984, 1987, 1990) Education 1972 Graduation from high school (Abitur, classical languages): Aloisiuskolleg, Bonn 1972-1974 Military service, reserve officer training 1974-1980 Law studies at Bonn and Tübingen Universities and at the London School of Economics and Political Science (with a focus on Public International Law, Philosophy of Law, Philosophy of Science) Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung scholarship (1975-1980) 1981/83 First/Second State Examination in Law Career 1981 Parliamentary Assistant to Carl Otto Lenz MP 1984 Federal Ministry of Defense: Counsellor, Contracts Department at the Federal Office of Defense Technology and Procurement 1984-1985 Federal Chancellery: Counsellor, Personnel Section 1985-1986 Federal Chancellery: Deputy Head, Cultural and State-Church Affairs Section 1986-1987 Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety: Bureau Chief, Minister’s Office 1987-1993 Federal Chancellery: Head, Speech Writing Section 1993-1995 Federal Chancellery: Director, Policy Planning 1995-1998 Federal Chancellery: Director-General, Policy Planning and Cultural Affairs 1998 Interim retirement after change of government 1998-2002 Weekly “Rheinischer -

Forty Years of the Grundgesetz (Basic Law)

German Historical Institute Washington, D.C. Occasional Paper No. 1 Forty Years of the Grundgesetz (Basic Law) The Basic Law — Response to the Past or Design for the Future? Peter Graf Kielmansegg Democratic Progress and SHadows of the Past Gordon A. Craig German Historical Institute Washington, D.C. Occasional Paper No. 1 Forty Years of the Grundgesetz (Basic Law) The Basic Law—Response to the Past or Design for the Future? Peter Graf Kielmansegg University of Mannheim Democratic Progress and Shadows of the Past Gordon A. Craig Stanford University 2 Edited by Prof. Dr. Hartmut Lehmann and Dr. Kenneth F. Ledford, in conjunction with the Research Fellows of the Institute © German Historical Institute, 1990 MACentire Graphics Published by the German Historical Institute Washington, DC 1759 R Street, N.W. Suite 400 Washington, D.C. 20009 Tel.: (202) 387–3355 3 Preface Nineteen eighty-nine is a year of many anniversaries. The city of Bonn celebrates its two-thousandth birthday, and the city of Hamburg invites us to celebrate the eight hundredth birthday of Hamburg harbor. Nineteen eighty-nine also marks the two-hundredth anniversary of the French Revolution, and it was 200 years ago that George Washington began his first presidency. Considering these historic dates, one may wonder why the German Historical Institute arranged two lectures marking the fortieth anniversary of the day on which the Basic Law of the Federal Republic of Germany was signed. In my view, this made sense. When the Federal Republic of Germany was founded forty years ago, memories of the Nazi terror were fresh in the minds of those who drew up the constitution for a new and better Germany. -

Selling the Economic Miracle Economic Reconstruction and Politics in West Germany, 1949-1957 Monograph Mark E

MONOGRAPHS IN GERMAN HISTORY VOLUME 18 MONOGRAPHS Selling the Economic Miracle Economic the Selling IN GERMAN HISTORY Selling The Economic Miracle VOLUME 18 Economic Reconstruction and Politics in West Germany, 1949-1957 Mark E. Spicka The origins and nature of the “economic miracle” in Germany in the 1950s continue to attract great interest from historians, economists, and political scientists. Examining election campaign propaganda and various public relations campaigns during this period, the author explores ways that conservative political and economic groups sought to construct and Selling the sell a political meaning of the Social Market Economy and the Economic Miracle, which contributed to conservative electoral success, constructed a Economic new understanding of economics by West German society, and provided legitimacy for the new Federal Republic Germany. In particular, the Miracle author focuses on the Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union’s (CDU/CSU) approach to electoral politics, which represented the creation of a more “Americanized” political culture reflected in the Economic Reconstruction borrowing of many techniques in electioneering from the United States, and Politics in West such as public opinion polling and advertising techniques. Germany, 1949-1957 Mark E. Spicka is Associate Professor of History at Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania. He received his Ph.D. from the Ohio State University in 2000 and was a Fulbright Scholar in Germany in 1996/1997. He has published a number of articles that have appeared in German Politics and Society, German Studies Review, and The Historian. Spicka E. Mark Cover Image: “Erhard keeps his promises: Prosperity for all through the social market economy” 1957 Bundestag election poster by Die Waage, Plakatsammlung, BA Koblenz. -

Randauszaehlungbrdkohlband

Gefördert durch: Randauszählungen zu Elitestudien des Fachgebiets Public Management der Universität Kassel Band 21 Die Politisch-Administrative Elite der BRD unter Helmut Kohl (1982 – 1998) Bastian Strobel Simon Scholz-Paulus Stefanie Vedder Sylvia Veit Die Datenerhebung erfolgte im Rahmen des von der Bundesbeauftragten für Kultur und Medien geförderten Forschungsprojektes „Neue Eliten – etabliertes Personal? (Dis-)Kontinuitäten deut- scher Ministerien in Systemtransformationen“. Zitation: Strobel, Bastian/Scholz-Paulus, Simon/Vedder, Stefanie/Veit, Sylvia (2021): Die Poli- tisch-Administrative Elite der BRD unter Helmut Kohl (1982-1998). Randauszählungen zu Elite- studien des Fachgebiets Public Management der Universität Kassel, Band 21. Kassel. DOI: 10.17170/kobra-202102193307. Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Einleitung ...................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Personenliste ................................................................................................................................ 4 3 Sozialstruktur .............................................................................................................................. 12 4 Bildung ........................................................................................................................................ 16 5 Karriere ....................................................................................................................................... 22 6 Parteipolitisches -

Pledge Fulfillment in Germany

PLEDGE FULFILLMENT IN GERMANY: AN EXAMINATION OF THE SCHRÖDER II AND MERKEL I GOVERNMENTS by MARK JOSEPH FERGUSON TERRY J. ROYED, COMMITTEE CHAIR BARBARA A. CHOTINER STEPHEN BORRELLI HARVY F. KLINE DANIEL RICHES A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Political Science in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Mark J. Ferguson 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Past scholarly research has indicated that campaign pledges are important. This research has led scholars to examine the various institutional differences between states. For instance, single-party majoritarian system, the British Westminster (UK), the American federal system for pledge fulfillment, coalition and minority systems, e.g., Ireland, Spain, Italy, France, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway and Sweden have been examined and compared. Combined, these scholars have presented academia compelling evidence that the rates of pledge fulfillment are a function of the individual institutional designs of the states examined. This dissertation expands on existing research by including the German system to the expanding understanding of pledge fulfillment and institutional design. This work examines the Schröder II (2002-2005) and Merkel (2005-2009) governments. I argue that there are several substantial questions that need to be addressed in relationship to Germany and pledge fulfillment. First, to what extent does the mandate model apply to Germany? Second, to what extent do parties in a grand coalition fulfill pledges, compared to normal coalition governments? Lastly, to what extent does the German case compare to previous research? I argue that pledge fulfillment under German coalition governments should be consistent with existing research; pledge fulfillment under grand coalition governments should be lower than previous research.