Do We Have Or Need a Two Speed Europe?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East

Istanbul Papers Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East: A Transatlantic Strategy for Partnership The Istanbul Papers were presented at: Istanbul Paper #1 The Atlantic Alliance at a New Crossroads Istanbul, Turkey A conference of: June 25 – 27, 2004 TURKıSH ECONOMıC AND SOCıAL STUDıES FOUNDATıON Core sponsorship: Additional support from: The German Marshall Fund TESEV TURKıSH ECONOMıC AND of the United States Bankalar Cad. No:2 K:3 SOCıAL STUDıES 1744 R Street, NW 34420 Karaküy/Istanbul FOUNDATıON Washington, DC 20009 T 212 292 89 03 T 1 202 745 3950 F 212 292 90 45 F 1 202 265 1662 W www.tesev.org.tr E [email protected] W www.gmfus.org Democracy and Human Development in the Broader Middle East: A Transatlantic Strategy for Partnership Istanbul Paper #1 i ii Authors* Urban Ahlin, Member of the Swedish Parliament Mensur Akgün, Turkish Economic and Social Science Studies Foundation Gustavo de Aristegui, Member of the Spanish Parliament Ronald D. Asmus, The German Marshall Fund of the United States Daniel Byman, Georgetown University Larry Diamond, Hoover Institution Steven Everts, Centre for European Reform Ralf Fücks, Heinrich Böll Foundation Iris Glosemeyer, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik Jana Hybaskova, Czech Member of the European Parliament Thorsten Klassen, The German Marshall Fund of the United States Mark Leonard, Foreign Policy Centre Michael McFaul, Stanford University Thomas O. Melia, Georgetown University Michael Mertes, Dimap Consult Joshua Muravchik, American Enterprise Institute Kenneth M. Pollack, The Brookings Institution Karen Volker, Office of Senator Joe Lieberman Jennifer Windsor, Freedom House * The views expressed in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, the authors’ affiliation. -

Payments and Market Infrastructure Two Decades After the Start of the European Central Bank Editor: Daniela Russo

Payments and market infrastructure two decades after the start of the European Central Bank Editor: Daniela Russo July 2021 Contents Foreword 6 Acknowledgements 8 Introduction 9 Prepared by Daniela Russo Tommaso Padoa-Schioppa, a 21st century renaissance man 13 Prepared by Daniela Russo and Ignacio Terol Alberto Giovannini and the European Institutions 19 Prepared by John Berrigan, Mario Nava and Daniela Russo Global cooperation 22 Prepared by Daniela Russo and Takeshi Shirakami Part 1 The Eurosystem as operator: TARGET2, T2S and collateral management systems 31 Chapter 1 – TARGET 2 and the birth of the TARGET family 32 Prepared by Jochen Metzger Chapter 2 – TARGET 37 Prepared by Dieter Reichwein Chapter 3 – TARGET2 44 Prepared by Dieter Reichwein Chapter 4 – The Eurosystem collateral management 52 Prepared by Simone Maskens, Daniela Russo and Markus Mayers Chapter 5 – T2S: building the European securities market infrastructure 60 Prepared by Marc Bayle de Jessé Chapter 6 – The governance of TARGET2-Securities 63 Prepared by Cristina Mastropasqua and Flavia Perone Chapter 7 – Instant payments and TARGET Instant Payment Settlement (TIPS) 72 Prepared by Carlos Conesa Eurosystem-operated market infrastructure: key milestones 77 Part 2 The Eurosystem as a catalyst: retail payments 79 Chapter 1 – The Single Euro Payments Area (SEPA) revolution: how the vision turned into reality 80 Prepared by Gertrude Tumpel-Gugerell Contents 1 Chapter 2 – Legal and regulatory history of EU retail payments 87 Prepared by Maria Chiara Malaguti Chapter 3 – -

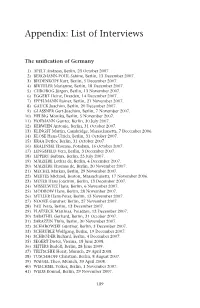

Appendix: List of Interviews

Appendix: List of Interviews The unification of Germany 1) APELT Andreas, Berlin, 23 October 2007. 2) BERGMANN-POHL Sabine, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 3) BIEDENKOPF Kurt, Berlin, 5 December 2007. 4) BIRTHLER Marianne, Berlin, 18 December 2007. 5) CHROBOG Jürgen, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 6) EGGERT Heinz, Dresden, 14 December 2007. 7) EPPELMANN Rainer, Berlin, 21 November 2007. 8) GAUCK Joachim, Berlin, 20 December 2007. 9) GLÄSSNER Gert-Joachim, Berlin, 7 November 2007. 10) HELBIG Monika, Berlin, 5 November 2007. 11) HOFMANN Gunter, Berlin, 30 July 2007. 12) KERWIEN Antonie, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 13) KLINGST Martin, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 7 December 2006. 14) KLOSE Hans-Ulrich, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 15) KRAA Detlev, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 16) KRALINSKI Thomas, Potsdam, 16 October 2007. 17) LENGSFELD Vera, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 18) LIPPERT Barbara, Berlin, 25 July 2007. 19) MAIZIÈRE Lothar de, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 20) MAIZIÈRE Thomas de, Berlin, 20 November 2007. 21) MECKEL Markus, Berlin, 29 November 2007. 22) MERTES Michael, Boston, Massachusetts, 17 November 2006. 23) MEYER Hans Joachim, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 24) MISSELWITZ Hans, Berlin, 6 November 2007. 25) MODROW Hans, Berlin, 28 November 2007. 26) MÜLLER Hans-Peter, Berlin, 13 November 2007. 27) NOOKE Günther, Berlin, 27 November 2007. 28) PAU Petra, Berlin, 13 December 2007. 29) PLATZECK Matthias, Potsdam, 12 December 2007. 30) SABATHIL Gerhard, Berlin, 31 October 2007. 31) SARAZZIN Thilo, Berlin, 30 November 2007. 32) SCHABOWSKI Günther, Berlin, 3 December 2007. 33) SCHÄUBLE Wolfgang, Berlin, 19 December 2007. 34) SCHRÖDER Richard, Berlin, 4 December 2007. 35) SEGERT Dieter, Vienna, 18 June 2008. -

Chapter 1 the Present and Future of the European Union, Between the Urgent Need for Democracy and Differentiated Integration

Chapter 1 The present and future of the European Union, between the urgent need for democracy and differentiated integration Mario Telò Introduction The European Union has experienced an unprecedented multi-dimensional and prolonged crisis, a crisis which cannot be understood in isolation from the international context, with major global economic changes to the detriment of the West. Opinions differ as to the overall outcome of the European policies adopted in recent years to tackle the crisis: these policies saved the single currency and allowed for moderate growth, but, combined with many other factors, they exacerbated the crisis of legitimacy. This explains the wave of anti-European sentiment in several Member States and the real danger that the European project will collapse completely. This chapter analyses the contradictory trends at play and examines more closely how to find a way out of this crisis – a way which must be built around the crucial role of the trade union movement, both in tackling Euroscepticism and in relaunching the EU. This drive to strengthen and enhance democracy in the euro area, and to create a stronger European pillar of social rights, will not be successful without new political momentum for the EU led by the most pro-European countries. The argument put forward in this chapter is that this new European project will once again only be possible using a method of differentiated integration. This paper starts with two sections juxtaposing two contradictory sets of data. On the one hand, we see the social and institutional achievements of the past 60 years: despite everything, the EU is the only tool available to the trade union movement which provides any hope of taming and mitigating globalisation (Section 1). -

The Jewish Contribution to the European Integration Project

The Jewish Contribution to the European Integration Project Centre for the Study of European Politics and Society Ben-Gurion University of the Negev May 7 2013 CONTENTS Welcoming Remarks………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………1 Dr. Sharon Pardo, Director Centre for the Study of European Politics and Society, Jean Monnet National Centre of Excellence at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev Walther Rathenau, Foreign Minister of Germany during the Weimar Republic and the Promotion of European Integration…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Dr. Hubertus von Morr, Ambassador (ret), Lecturer in International Law and Political Science, Bonn University Fritz Bauer's Contribution to the Re-establishment of the Rule of Law, a Democratic State, and the Promotion of European Integration …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………8 Mr. Franco Burgio, Programme Coordinator European Commission, Brussels Rising from the Ashes: the Shoah and the European Integration Project…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………13 Mr. Michael Mertes, Director Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, Israel Contributions of 'Sefarad' to Europe………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………21 Ambassador Alvaro Albacete, Envoy of the Spanish Government for Relations with the Jewish Community and Jewish Organisations The Cultural Dimension of Jewish European Identity………………………………………………………………………………….…26 Dr. Dov Maimon, Jewish People Policy Institute, Israel Anti-Semitism from a European Union Institutional Perspective………………………………………………………………34 -

Flexibility Within the Lisbon Treaty: Trademark Or Empty Promise?

EIPASCOPE 2008/1 Flexibility within the Lisbon Treaty Flexibility within the Lisbon Treaty: Trademark or Empty Promise? By Funda Tekin and Prof. Dr Wolfgang Wessels1 The concept of flexibility in the European integration process has been discussed in different ways since the 1970s. Some forms may be “upwardly oriented”, representing a driving force rather than a brake on the integration process. Others may weaken integration and have a “downsizing” effect. “Enhanced cooperation”, which was first introduced by the Amsterdam Treaty, aims to provide an attractive alternative to intergovernmental cooperation outside the treaty, and to allow a group of Member States to deepen integration in particular areas without 25 affecting either the interests of others or the overall construction of European integration. The Lisbon Treaty introduces changes at all stages of the cycle: preparatory stage, initiation, authorisation, implementation, accession and termination. The conditions for enhanced cooperation remain restrictive and other forms of flexibility may seem more attractive. Consequently the prospect is for flexibility to be an empty promise rather than a trademark of the new Treaty. Introduction ○○○○○○○○○○○ flexibility are analysed in the light of the decision-making dilemma in which procedures are revised between a The idea of flexibility in the integration process has long sovereignty-led veto reflex and a functional drive for efficiency been the subject of European debate. The best-known (Hofmann and Wessels 2008). Given the restricted -

Alois Mertes

ALOIS MERTES WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN Dr. Alois Mertes (1921–1985) war einer der profiliertestenaußenpolitischenDenkerundein bedeutenderVertreterdespolitischenKatholizis- HANNSJürgENKüStErS(HrSg.) musinderBundesrepublikDeutschland.Von 1952angehörteerdemAuswärtigenDienstder BundesrepublikDeutschlandan.Derprofunde KennerdersowjetischenAußen-undSicherheits- politikavanciertezudemzumaußenpolitischen Ratgeber der Unionsparteien. DieKonrad-Adenauer-Stiftunge.V.erinnerte am7.November2012miteinerVeranstaltung imWeltsaaldesAuswärtigenAmtesinBonn andiesenüberzeugtenEuropäerundPatrioten. DervorliegendeBandfasstdieimVerlaufder PräsentationgehaltenenAnsprachenzusammen. www.kas.de ALOIS MERTES – WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN REDEBEITRÄGE ANLÄSSLICH DER VERANSTALTUNG AM 7. NOVEMBER 2012 IM WELTSAAL DES AUSWÄRTIGEN AMTES IN BONN ALOIS MERTES – WÜRDIGUNG EINES CHRISTLICHEN DEMOKRATEN REDEBEITRÄGE ANLÄSSLICH DER VERANSTALTUNG AM 7. NOVEMBER 2012 IM WELTSAAL DES AUSWÄRTIGEN AMTES IN BONN HANNS JÜRGEN KÜSTERS (HRSG.) © 2013, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Sankt Augustin/Berlin Das Werk ist in allen seinen Teilen urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung ist ohne Zustimmung der Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V. unzulässig. Das gilt insbesondere für Vervielfältigungen, Übersetzungen, Mikroverfilmungen und die Einspeicherung in und Verarbeitung durch elektronische Systeme. www.kas.de Gestaltung: SWITSCH Kommunikationsdesign, Köln Umschlagfoto: Alois Mertes im -

The Memory of the Century

Institut für Spring 2001 die Wissenschaften vom Menschen Institute for Human Sciences A-1090 Wien Spittelauer Lände 3 Tel. (+431) 313 58-0 Fax (+431) 313 58-30 CONFERENCE The IWM’s first major conference of the year took place March [email protected] www.iwm.at 9th through the 11th at the Palais Ferstel in central Vienna. Scholars and public figures from around the world gathered to discuss the problem of historical memory, a problem that has moved into the center of political, social, and cultural debates in Contents many countries as they reflect upon the recent past. 9 Workshop Citizenship and Identity The Memory of the Century 11 Kolloquium Offene Seele – Harmonische Welt FRENCH PHILOSOPHER Paul Ricoeur opened the conference 12 Conference on Friday evening, March 9th with a public lecture on the When Globalization Fails... relation between memory and history. As in his main work, Temps et Récit, Ricoeur’s arguments in this keynote speech 15 Seminar with Slavenka Drakulic revolved around the presence of the absent in our imagina- The Politics of Truth and Justice tion, which he identified as the main problem of epistemo- logical and chronological reflection and hence of philoso- 25 Notes on Books phy and history in general. According to Ricoeur, the inter- Charles Taylor on Multiple secting lines of “actual presentation” and “representation of Modernities the past” constitute a riddle in the phenomenon of Sorin Antohi on Ioan Petru Culianu memory with respect to the question of truth. The talk’s three parts considered memory as the fundamental matrix, 26 Guest Contributions the external object, and the informed product of history, Michel Serres and Pierre Nora and addressed the paradoxes that result from these differ- on Memory ent functions. -

Grußwort JCPA-Europakonferenz P

Greetings to the Participants of the JCPA/KAS Israel Conference “Europe an Israel: A New Paradigm” by Michael Mertes, Director of KAS Israel Jerusalem, March 24th, 2014 On behalf of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung, I warmly welcome you to this very topical conference. I would also like to thank our tried-and-tested partner, the Jerusalem Center for Public Affairs, for the excellent cooperation in preparing today’s event. The Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung is a German political foundation dedicated to national as well as international think-tank work and dialogue. We are active around the globe with some 80 offices reaching out to more than 120 countries, and we have been working in Israel for more than 30 years. Let me just say a couple of words about the stake my organization has in this joint conference. Most importantly, it’s the legacy of Konrad Adenauer, the first Chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany. He was also one of the founding fathers of what is now the European Union. The friendship between him and David Ben-Gurion laid the foundation for the friendship uniting Germany and Israel today. We take great pride in bearing Konrad Adenauer’s name. We also take pride in carrying on the legacy of German Chancellor Ludwig Erhard, under whose leadership (and that of Israeli Prime Minister Levi Eshkol) diplomatic relations between Germany and Israel were established in 1965, almost 50 years ago. Today’s successor of Adenauer and Erhard, German Chancellor Angela Merkel, is a member of our foundation’s board. We fully support her clear stance on Israel: Germany will never be neutral on Israel, and Israel can be sure of German support when it comes to ensuring its security. -

Enhanced Cooperation and the Tension Between Unity and Asymmetry in the EU by Carlo Maria Cantore*

ISSN: 2036-5438 We're one, but we're not the same: Enhanced Cooperation and the Tension between Unity and Asymmetry in the EU by Carlo Maria Cantore* Perspectives on Federalism, Vol. 3, issue 3, 2011 Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 1 Abstract The aim of this article is to analyse one of the main features of asymmetry in the EU legal order: enhanced cooperation. After the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty, two enhanced cooperation schemes (on divorce and patent) have already seen the light of the day. The paper first focuses on the evolution of the rules on "closer cooperation"/"enhanced cooperation" from the Treaty of Amsterdam onwards, then it analyses the first two cases. Enhanced cooperation is a unique test to understand how the EU manages to balance unity and asymmetry, thus an analysis of the rules and the relevant practice is very useful to this extent. The last section of the paper compares asymmetric integration at the EU and the WTO level, in order to understand how different legal orders deal with sub-unions and what degree of asymmetry can a system tolerate. Key-words Enhanced Cooperation, Asymmetry, Lisbon Treaty, Preferential Trade Agreements Except where otherwise noted content on this site is licensed under a Creative Commons 2.5 Italy License E - 2 1. Introduction - Asymmetry: rule or exception? Over the last decades, an impressive number of scholars have investigated the issue of the nature of the European Union legal order (Weiler, 1991; Amato et al. -

A Multi-Speed Europe. a View from Romania

Research Paper Multi-speed Europe. A view from Romania Ist edition Mihai SEBE December 2019, Bucharest, Romania A Multi-speed Europe. View from Romaniai By Mihai SEBE, PhD Bucharest, Romania Abstract: The idea of a multi-speed Europe has become a topic of debate at the European level since the early 1990’s as our continent faced the enormous pressures of change induced by the collapse of the communist system in Eastern and Central Europe followed by the continuous reform of the European Communities and later on of the European Union and its process of eastward enlargement. This debate steamed up after the Brexit Referendum of 2016 as the multi-speed Europe appeared to be one of the solutions of coming up from the crisis. Following the Sibiu Declaration of 2019 that spoke of one Europe and the European Parliament elections, the topic seems to have become dormant for the time being as the political energies are focused upon solving more immediate issues. Keywords: Brexit; multi-speed Europe; Europe a la carte; Romania. Disclaimer: This publication is a working paper, and hence it represents research in progress and it received financial support from the European Parliament. Sole liability rests with the author alone and does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any organization he is connected to and the European Parliament is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information contained therein. With the financial support of the European Parliament 2 Contents A. What’s in a name? Multi-speed Europe. Conceptual history............................................... -

Meeting the Challenges of Globalisation Requires Enhanced Cooperation Between the ESS and the ESCB

Document IV/4 - Meeting the challenges of globalisation requires enhanced cooperation between the ESS and the ESCB Steven KEUNING, Director General Statistics, European Central Bank International cooperation in the area of statistics is crucial to face the challenges of an increasingly globalised world. Since a very large share of cross-border transactions of EU-countries occurs within the EU, the existing European statistical setting (EU and ECB legal acts, together with effective coordination bodies), clearly facilitates this cooperation. Furthermore, statistical authorities must strive to minimise the costs for respondents by sharing already existing information to the extent possible and by looking for new collaboration models to collect data from multinationals. This paper addresses some of these issues. 1. Introduction In his keynote speech at the third ECB Conference on Statistics “Financial Statistics for a global economy”, Nouriel Roubini[1] concluded that “There is a serious need for better financial statistics in an increasingly globalised world. There is a significant global public goods nature of such statistics in a world where cross- border financial transactions are becoming more and more important. Thus, there is a need for greater cooperation between national and international authorities that collect and compile such statistics; greater sharing of information is essential even if, often, national authorities are somehow territorial about sharing such economic and financial data and information with foreign and international authorities. There are also, of course, complex issues of the relative costs and benefits of greater financial statistics and who should be paying for such costs. But the need for better data to capture financial globalisation is undeniable and should be on the agenda of international economic and financial cooperation.” ECB President Trichet[1] also 1 noted, in his closing speech, that “… euro area statistics lie at the heart of the ECB’s monetary policy-making.