CONTENTS Number 1 ARRTICLESTICLES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certamen Coral De Tolosa 2017

Antolatzailea Organizador Tolosako Ekinbide Etxea Centro de Iniciativas de Tolosa Babesleak Patrocinadores Laguntzaile bereziak Ohorezko lehendakaria Excmo.Sr.D. Iñigo Urkullu Colaboradores especiales Presidente de honor Eusko jaurlaritzako lehendakaria Ohorezko batzordea Excmo. Sr. D. Markel Olano Comité de honor Gipuzkoako foru aldundiko aldun nagusia Excmo. Sr. D. Bingen Zupiria Eusko jaurlaritzako kultura kontseilaria Ilmo. Sra. Dña. Olatz Peon Tolosako alkatea Laguntzaileak Agua de Insalus Colaboradores Colegio Hirrikide Jesuitinak Comunidad Convento Santa Clara Distribuciones Mendieta Batzorde exekutiboa D. Julián Lacunza Euskalherriko abesbatzen elkartea Comité ejecutivo D. Luis Miguel Espinosa Harizpe D. Xabier Ormazabal 4 5 Kaiz Lorategia Dña. Idoya Otegui P.P. Franciscanos Sociedades populares de tolosa Udaberri dantza taldea Batzorde teknikoa D. Enrique Azurza Comité técnico D. Jon Bagües D. Javier Busto D. José Antonio Sainz Alfaro D. Xabier Sarasola tolosako abesbatza lehiaketa · certamen coral de tolosa · concours choral de tolosa · tolosa choral contest tolosako abesbatza lehiaketa · certamen coral de tolosa · concours choral de tolosa · tolosa choral contest Lehiaketako batzordeak / Comités del certamen Batzorde artistikoa Luis Miguel Espinosa Musika artxiboa Zerkausiko bazkariak Mónica Alfaro Abesbatza laguntzaileak Imanol Aramendi Xabier Ormazabal Comité artístico (Director) Archivo musical Comidas Zerkausi José Luis García Acompañantes coros Raquel Etxabe Xabier Ormazabal Janariak S.A. Aitor Imaz CD-aren edizioa Aitor -

MUSICA MUNDI WORLD RANKING LIST - TOP 1000 Choirs 1 / 38

MUSICA MUNDI WORLD RANKING LIST - TOP 1000 Choirs 1 / 38 Position Choir Conductor Country Points 1 Jauniešu Koris KAMER.. Maris Sirmais Latvia 1221 2 University of Louisville Cardinal Singers Kent Hatteberg USA 1173 3 Guangdong Experimental Middle School Choir Ming Jing Xie China 1131 4 Stellenbosch University Choir André van der Merwe South Africa 1118 4 Elfa's Singers Elfa Secioria Indonesia 1118 6 Stellenberg Girls Choir André van der Merwe South Africa 1113 7 Victoria Junior College Choir Nelson Kwei Singapore 1104 8 Hwa Chong Choir Ai Hooi Lim Singapore 1102 9 Mansfield University Choir Peggy Dettwiler USA 1095 10 Magnificat Gyermekkar Budapest Valéria Szebellédi Hungary 1093 11 Coro Polifonico di Ruda Fabiana Noro Italy 1081 12 Ars Nova Vocal Ensemble Katalin Kiss Hungary 1078 13 Shtshedrik Marianna Sablina Ukraine 1071 14 Coral San Justo Silvia Francese Argentina 1065 Swingly Sondak & Stevine 15 Manado State University Choir (MSUC) Indonesia 1064 Tamahiwu 16 VICTORIA CHORALE Singapore Nelson Kwei Singapore 1060 17 Kearsney College Choir Angela Stevens South Africa 1051 18 Damenes Aften Erland Dalen Norway 1049 19 CÄCILIA Lindenholzhausen Matthias Schmidt Germany 1043 20 Kamerny Khor Lipetsk Igor Tsilin Russia 1042 20 Korallerna Eva Svanholm Bohlin Sweden 1042 22 Pilgrim Mission Choir Jae-Joon Lee Republic of Korea 1037 23 Gyeong Ju YWCA Children's Choir In Ju Kim Republic of Korea 1035 24 Kammerkoret Hymnia Flemming Windekilde Denmark 1034 Elfa Secioria & Paulus Henky 25 Elfa's Singers Indonesia 1033 Yoedianto 26 Music Project Altmark West Sebastian Klopp Germany 1032 27 Cantamus Girls' Choir Pamela Cook Great Britain 1028 28 AUP Ambassadors Chorale Arts Society Ramon Molina Lijauco Jr. -

Classical New Release

harmonia mundi UK JUNE 30 2014 Classical new release Maria Joao Pires joins Onyx available 30th June & July 14, call-off 20th June BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE, CHOICES July Naïve V5344 Mister Paganini: Laurent Korcia Glossa GCD922803 Gesualdo Responsoria: La Compagnia del Madrigale GRAMOPHONE, EDITOR’S CHOICE, July Orfeo C878141A Strauss Also sprach, Don Juan, Till Eulenspiegel: CBSO, Andris Nelsons IRR OUTSTANDING, June BBC MUSIC MAGAZINE CHOICE June Opera Magazine, DISC OF THE MONTH Signum SIGCD372 Bartok Bluebeard’s Castle: Sir John Tomlinson, Philharmonia, Esa-Pekka Salonen IRR OUTSTANDING, June Pan Classics PC10305 C.P.E. Bach Works for Keyboard & Violin: Leila Schayegh ALBUM OF THE WEEK, Sunday Times, 11th May GLOSSA GCD921119 Mozart The Last Three Symphonies: Orchestra of the 18th Century, Frans Brüggen BBC RADIO 3, CD OF THE WEEK, CD REVIEW Naive V5373 Handel Tamerlano / Sabata, Cencic, Minasi DISTRIBUTED LABELS: ACCENT RECORDS, ACTES SUD, AGOGIQUE, ALIA VOX, AMBRONAY, APARTE, ARTE VERUM, AUDITE, BEL AIR, THE CHOIR OF KINGS COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE, CONVIVIUM, CHRISTOPHORUS, CSO RESOUND, DELPHIAN, DUCALE, EDITION CLASSICS, FLORA, FRA MUSICA, GLOSSA, harmonia mundi, HAT[NOW]ART, LA DOLCE VOLTA, LES ARTS FLORISSANTS EDITIONS, LSO LIVE, MARIINSKY, MIRARE, MODE, MUSO, MYRIOS, NAÏVE, ONYX, OPELLA NOVA, ORFEO, PAN CLASSICS, PRADIZO, PARATY, PEARL, PHILHARMONIA BAROQUE, PHIL.HARMONIE, PRAGA DIGITALS, RADIO FRANCE, RAM, REAL COMPAÑIA ÓPERA DE CÁMARA, RCO LIVE, SFZ MUSIC, SIGNUM, STRADIVARIUS, UNITED ARCHIVES, WAHOO, WALHALL ETERNITY, WERGO, WIGMORE HALL LIVE, WINTER & WINTER, YSAYE RELEASE DATE 14TH JULY 2014 LISZT: Sonata in B minor, Late pieces Paul Lewis Editor’s Choice, Gramophone *****, The Guardian Radio 3 Disc of the Week Gramophone Critics’ Choice Pianist Recommended "The poetry and grandeur of his playing put Paul Lewis's Liszt among the Greats…even in a crowded market place (where Horowitz, Gilels, Richter, Argerich, Brendel and Pollini, etc, jostle for attention) Paul Lewis's recording stands out for its breadth, mastery and shining musicianship. -

Sing It Like a Native Latin-American and Caribbean Choral Music

June/July 2014 CONTENTS Vol. 54 • no 11 Giving Patient Hope ŅŠ Jean Gilles’s Messe des Morts: to the Exile: A Study in Contextual Rethinking KASPARS PUTNI Period Performance Brahms’s Requiem A VISION OF DIVERSITY 8 18 32 ARTICLES INSIDE 8 Jean Gilles’s Messe des Morts: A Study in Contextual Period Performance 2 From the Executive Director 4 From the President by Mark Ardrey-Graves 5 From the Editor 6 Letters to the Editor 18 Giving Patient Hope: Rethinking Brahms’s Requiem 42 International Conductor Exchange Application by Jeffrey J. Faux and David C. Rayl 54 2015 National Honor Choir Information 56 2015 National Conference Information 32 Kaspars Putninš:, A Vision of Diversity 60 Brock Student Composing Competition 65 Herford Prize Call for Papers by Vance Wolverton 67 In Memoriam 80 Index for Volume 54 47 On the Voice edited by Sharon Hansen 92 Advertisers’ Index Choral Directors Are from Mars and Voice Teachers Are from Venus: “Sing from the Diaphram” and Other Vocal Mistructions, Part 2 The Choral Journal is the official publication of The American by Sharon Hansen, Allen Henderson, Scott McCoy, Choral Directors Association (ACDA). ACDA is a nonprofit professional organization of choral directors from schools, Donald Simonson, and Brenda Smith colleges, and universities; community, church, and profes- sional choral ensembles; and industry and institutional organizations. Choral Journal circulation: 19,000. Annual dues (includes subscription to the Choral Journal): COLUMNS Active $95, Industry $135, Institutional $110, Retired $45, and Student $35. One-year membership begins on date of dues acceptance. Library annual subscription rates: U.S. -

Fall 2016 Concert Program

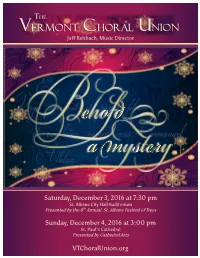

Jeff Rehbach, Music Director Saturday, December 3, 2016 at 7:30 pm St. Albans City Hall Auditorium Presented by the 8th Annual St. Albans Festival of Trees Sunday, December 4, 2016 at 3:00 pm St. Paul’s Cathedral Presented by Cathedral Arts VTChoralUnion.org The Vermont Choral Union, Fall 2016 Soprano Tenor Celia K. Asbell Burlington Mark Kuprych Burlington Ellen Bosworth Shelburne Rob Liotard Starksboro Mary Dietrich Essex Junction Jack McCormack Burlington Megumi Esselstrom Essex Junction Pete Sandon Essex Ann K. Larson* Essex Junction Paul Schmidt Bristol Kathleen Messier Essex Junction James Turner St. Albans Kayla Tornello Essex Junction Maarten van Ryckevorsel* Winooski Lindsay Westley Hinesburg Gail Whitehouse* Burlington Bass Martha Whitfield Charlotte James Barickman Underhill Douglass Bell* St. Albans Alto Jim Bentlage Jericho Clara Cavitt Jericho Jonathan Bond Burlington Michele Grimm* Burlington Joe Comeau Alburgh Mary Ellen Jolley* St. Albans Robert Drawbaugh Essex Junction Terry Lawrence Burlington John Houston Lisa Raatikainen Burlington Larry Keyes* Colchester Charlotte Reed Underhill Richard Reed Morrisville Lynn Ryan Colchester Dan Velleman Burlington Maureen Sandon Essex * Board members Karen Speidel Charlotte About the Vermont Choral Union Originally called the University of Vermont Choral Union, the ensemble was founded in 1967 by James G. Chapman, Professor of Music at the University of Vermont, who directed the choir until his retirement in 2004. Music educator and singer Gary Moreau then served as director through 2010. Carol Reichard, director of the Colchester Community Chorus, served as the Choral Union's guest conductor in Spring 2011. The Vermont Choral Union welcomed Jeff Rehbach as its music director in Fall 2011. -

3Rd CHOIR OLYMPICS

3rd CHOIR OLYMPICS 2004 Bremen, Germany Results Choir-Olympic Qualifying Competition Category 1: Children’s Choirs name of the choir Country Code Conductor Points Diploma Kamerton Russia RUS Lilia Sapryga 25,23 GOLD V Oakville Children's Choir Canada CAN Glenda Crawford 24,83 GOLD V Radost Russia RUS Tatyana Zhdanova 24,44 GOLD IV CCC Kei Wan School Choir China PRC On-Lai Anne Chu 23,64 GOLD IV & Yin-Ping Sinlia Siu Dhetsky Khor "Rhapsodia" Russia RUS Irina Kachkalova 23,56 GOLD IV Dhetsky Khor "Harmonia" Russia RUS Ludmila Shevchenko 23,55 GOLD IV Guang Xi Shao Er Guang Bo He Chang Tuan China PRC Shan Hua 23,54 GOLD IV Dalian Youth Palace Choir China PRC Xiu Xua Gong 22,49 GOLD II Rassvet Russia RUS Galina Potopyak 22,33 GOLD II Taipei Hua-Shin Children's Chorus Chinese Taipei ROC Yun-Hung Chen 21,89 GOLD II Cantilena Russia RUS Alfred Prinz 21,33 GOLD I & Margarita Skatshkova Shkolny korabl Ukraine UA Galina Voytsekhivska 21,30 GOLD I & Olga Polishtshuk Gene Louw Children's Choir South Africa RSA Marietjie Martinson 21,25 GOLD I & Estelle Brand MEZ - Dhetsky Khor Krasnodar Russia RUS Evgenia Zhukova 21,09 GOLD I & Margarita Ambartsumyan Corul de copii JUNIOR V.I.P Romania RO Anca-Mona Marias 20,54 GOLD I & Mihael Corneliu Bacalu Berkshire Girls' Choir Great Britain GB Gillian Dibden 20,53 GOLD I & Mark Griffiths Beijing International Children's Choir China PRC Qun Chen 20,46 SILVER X Sinaya Ptitsa Russia RUS Petr Voronov 20,45 SILVER X Phoenix Children's Chorus - Concert Choir USA USA Ron Carptenter 20,44 SILVER X Rainbow Children's -

Pod Pokroviteljstvom Evropske Komisarke Ge. Androulle Vassilliou Under the Patronage of Mrs Androulla Vassiliou, Member of the E

Pod pokroviteljstvom evropske komisarke ge. Androulle Vassilliou Under the patronage of Mrs Androulla Vassiliou, Member of the European Commission EGP_knjižica012.indd 1 12.4.12 9:54 Javni sklad RS za kulturne Organizatorji Organizacijski odbor dejavnosti z območno izpostavo Maribor Organisers Organising Committee Organizacijski odbor tekmovanja Predsednik Mestna občina Maribor President Javni sklad RS za kulturne dejavnosti Franc Kangler in Območna izpostava Maribor župan mestne občine Maribor Zveza kulturnih društev Slovenije Zveza kulturnih društev Maribor Mestna občina Maribor Člani Organising Committee of the Competition Members Municipal Community Maribor Maja Čepin Čander Republic of Slovenia Public Fund Urška Čop Šmajgert for Cultural Activities Mihela Jagodic and it’s Regional Office in Maribor mag. Franci Pivec Union of Cultural Societies of Slovenia Jože Protner Zveza kulturnih društev Union of Cultural Societies of Maribor Marjan Pungartnik Maribor Brigita Rovšek Daniel Sajko mag. Igor Teršar Matija Varl Zveza kulturnih društev Slovenije 2 EGP_knjižica012.indd 2 12.4.12 9:54 European Grand Prix for Choral Singing Association www.gpeuropa.org Tekmovanje za veliko zborovsko nagrado Evrope (European Grad Prix for The European Grand Prix for Choral Singing is an annual choral competition Choral Singing) je vsakoletno tekmovanje zmagovalcev šestih zelo zahtevnih between the winners of six European choral competitions of very high artistic evropskih zborovskih tekmovanj, združenih v zvezo za veliko nagrado quality. Evrope. It was created in 1988 through the initiative of the competitions Concorso To so leta 1988 ustanovila tekmovanja Concorso Polifonico Guido d’ Arezzo, Polifonico Guido d’ Arezzo, Arezzo (Italy), Béla Bartók International Choir Arezzo (Italija), Béla Bartók International Choir Competition Debrecen Competition Debrecen (Hungary), Concorso C. -

Œdipus Rex / Symphonie De Psaumes Igor Stravinski

Œdipus Rex / Symphonie de Psaumes Igor StravInSkI 1 Les êtres passent, le Festival avance Selon le mot de Jean de La Fontaine, « toute puissance est faible, à moins que d’être unie ». Si nous Le 68e Festival d’Aix sera le premier sans Edmonde Charles-Roux, l’une de ses fondatrices, disparue au pouvons nous réjouir aujourd’hui de cette 68ème édition du Festival d’Aix-en-Provence, il nous faut printemps. Nul doute que son souvenir hantera les représentations de cet été. Elle avait été l’une des rendre hommage à la collaboration exemplaire qui unit dans cet édifice l’ensemble des équipes du personnes qui avaient porté le Festival sur les fonts baptismaux, en 1948, avec la comtesse Lily Pastré Festival, artistes, techniciens du spectacle, partenaires et mécènes de tous horizons. Année après et Gabriel Dussurget. année, la participation active d’acteurs multiples garantit la bonne santé et la vitalité du Festival, qui se tourne encore un peu plus vers l’international, à travers un partenariat ambitieux avec le Beijing Gabriel Dussurget, lui, nous a quittés en 1996, voici tout juste vingt ans. Le Musée du Palais de Music Festival. l’Archevêché – anciennement Musée des Tapisseries – et le conservatoire Darius-Milhaud ont décidé de lui rendre hommage, le premier à travers une exposition, le second avec un concert. Sûr de ses forces, le Festival poursuit son ouverture au monde que je salue, comme en atteste la création mondiale de Kalîla wa Dimna de Moneim Adwan, qui mélange de façon inédite les langues Les êtres passent, le Festival demeure, et avance. -

Lotta Wennäkoski at 50 Focus on Carl Unander-Scharin

NORDIC HIGHLIGHTS 4/2019 NEWSLETTER FROM GEHRMANS MUSIKFÖRLAG & FENNICA GEHRMAN Lotta Wennäkoski at 50 Focus on Carl Unander-Scharin NEWS Fennica takes over Warner’s Rautavaara’s Vigiliagilia light catalogue Einojuhani Rautavaarara’s’s All-Night Vigil (Vigilia)a) As of 1 January 2020, Fennica Gehrman will Ondine Records Photo: Photo: Elin, Model House Elin, Photo: be acting as agent for the orchestral material is a new release on the BIBISS of Warner/Chappell Music Finland. Under label. Nils Schweckendiekdiek the new agreement, nearly 300 works, mainly conducts the Helsinki light-orchestra arrangements, will from then on- Chamber Choir, and wards be distributed by Fennica. Th e bulk will the soloists are Niall consist of works by George de Godzinsky, Rau- Chorell, tenor and no Lehtinen, Toivo Kärki and Unto Mononen, Tuukka Haapaniemi, among others. Many of them are in versions bass. made by diff erent arrangers. In 1971-72 Rau- tavaara composed a Finnish Orthodox church service similar to that of Rach- Photo: Camilla Svensk Camilla Photo: maninov, comprising Vespers as well as Matins. He then reshaped the music into what we now Tebogo Monnakgotla know as Vigilia, Monnakgotla’s Un clin d’oeil a concert version forming a musical entity. Th e 70-minute work Tebogo Monnakgotla’s acclaimed song cycle Albert Schnelzer is in 34 sections and features prominent parts Un Clin d’oeil to poems by the Madagascan poet for a bass and a tenor soloist. Jean-Joseph Rabearivelo, will be heard again in spring 2020. Baritone Luthando Qave will be Swedish MPA Award to Schnelzer soloist with the Norrköping Symphony under Albert Schnelzer has been awarded the Swed- Heino Kaski piano album Marc Soustrot on 29 February, and Anja Bihl- ish Music Publishers’ Prize 2019 for his Piano Fennica Gehrman has published a treasure maier will lead the Nordic Chamber Orchestra Concerto – Th is is Your Kingdom . -

July 2014 List Blu-Ray New Releases

BLU-RAY NEW RELEASES Arthaus 108 111 Gluck 300 Years - Alceste, Iphigenie en Tauride, Orfeo ed Euridice (all on one disc) Carydis;Christie;Haenchen £49.95 C Major Entertainment 716 804 Verdi & Wagner The Odeonsplatz Concert with Rolando Villazon and Thomas Hampson Bavarian Radio SO;Nezet-Seguin £29.95 717 004 El Sistema at the Salzburg Festival Mahler, Gershwin, Ginastera etc National Children's SO of Venezuela;Rattle £29.95 Dreyer Guido DVDDG BR21081 Respighi Belkis, Queen of Sheba (concert performance) Doufexis;Moratzaliev;Stuttgart PO;Feltz £24.95 Euroarts 207 2184 Karl Bohm in rehearsal and performance of Richard Strauss' Don Juan VPO £24.95 207 2674 Haydn The Seasons Roschmann;Schade;Boesch;VPO;Harnoncourt £29.95 Opus Arte OABD 7145 D Strauss, R Ariadne auf Naxos (Glyndebourne 2013) Isokoski;Lindsey;Claycomb;Skorokhodov;Allen;LPO;Jurowski £29.95 OABD 7147 D Wagner Der fliegende Hollander (Bayreuth 2013) Youn;Selig;Merbeth;Muzek;Mayer;Gloger £29.95 OABD 7150 D Rameau Hippolyte et Aricie (Glyndebourne 2013) Lyon;Karg;Connolly;Degout;OAE;Christie £24.95 Sony 88843 070999 Summer Night Concert 2014 Works by Berlioz, Liszt, J Strauss II and R Strauss Lang Lang;VPO;Eschenbach £16.95 88843 005739 Mozart Die Zauberflote 2DVD Richter;Kleiter;Fredrich;Zeppenfeld;Concentus Musicus Wien;Harnoncourt £16.95 88843 005759 Strauss, R Ariadne auf Naxos 2DVD Kaufmann;Magee;Mosuc;VPO;Harding £16.95 Dear Customer, As we now head into the summer months, new releases start to get slightly thinner on the ground, but thankfully there are still some titles we can get excited about. Some of you may remember a thrilling Prom concert last year that featured French orchestra Les Siecles performing tel 0115 982 7500 fax 0115 982 7020 Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring on instruments that would have been used at the first performance in 1913. -

30 September 2016 Page 1 of 12

Radio 3 Listings for 24 – 30 September 2016 Page 1 of 12 SATURDAY 24 SEPTEMBER 2016 5:11 AM 10.35am Kathleen Ferrier and the Year 1946 Alpaerts, Flor (1876-1954) Kathleen Ferrier©s 1946 recording of Gluck©s ©What is Life?© (`Che SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b07vwsmc) Avondmuziek farò senza Euridice' from Orfeo ed Euridice). Hilary Finch looks Bach, Vivaldi and Piazzolla from Richard Galliano with Solistes I Solisti del Vento, Ivo Hadermann (conductor) at a recording which seemed to hold within it the hopes, fears, Europeens, Luxembourg 5:20 AM and lingering grief of its day - and it became an icon of its time. Britten, Benjamin (1913-1976) Accordion player Richard Galliano features in a programme of Hymn to St Cecilia for chorus (Op.27) Kathleen Ferrier: The Complete Decca Recordings Bach, Vivaldi & Piazzolla with Solistes Européens, Luxembourg BBC Singers, David Hill (conductor) DECCA 4783589 (14CD) and conductor Christoph König. With Jonathan Swain. 5:31 AM 1:01 AM Hess, Willy (1906-1997) 10.50am Recordings of music from 1946 Bach, Johann Sebastian [1685-1750] Suite in B flat major for piano solo (Op.45) Mark Lowther joins Andrew to look at recordings of music Concerto no. 1 in A minor BWV.1041 for violin and string Desmond Wright (Piano) premiered in 1946 by composers including Richard Strauss, orchestra, arranged for accordion 5:42 AM Aaron Copland and Charles Ives. Together they compare Richard Galliano (accordion), Solistes Européens, Luxembourg, Kodaly, Zoltán (1882-1967) recordings by artists associated with the works© premieres with Christoph König (conductor) Adagio more recent versions. -

Critic's Pick 1

Critic’s Pick …1 A Spotless Rose (FOOTPRINT Records FRCD-060) Sofi a Vokalensemble, Bengt Ollén conductor 99 any of you, I hope, share my enthusiasm for this year’s Olympic Games. I was particularly struck this year by the men and women’s gymnastics, where the competitors are evaluated not only on the difficulty of their individual routines, but Malso on the elegance with which they execute their routine. One of the things I most admire about these performances is the level of gracefulness that the judges expect of their final landing. Gymnasts, after performing their myriad jumps, leaps, and flips, are then required to land without faltering! The descents between moves, and particularly the final landing, are critical to a successful performance. This same gracefulness is expected of choral groups, but instead of landings, we call them cadences. The Sofia Vokalensemble masters such acrobatic routines, and performs with a level of sophistication, elegance, and nuance that make things sound easy to the listener. Furthermore, they have a superior understanding of phrasing and pitch-perfect cadences. Reviewed by The recording ‘A Spotless Rose’, features mainly a cappella works for the Advent season, featuring soprano Jeanette Kohn, violinist Bartoscz Cajier, and organist Henrik Ariestrand. Jonathan Slawson Founder and conductor Bengt Ollén leads the internally acclaimed ensemble, recipient of the 2012 Journalist European Grand Prix for Choral Singing, the 2009 Grand Prix at the International Choral Festival in Norway, and the 2008 Grand Prix in Italian Gorizia, among many others. In simple terms, I offer my highest praise for this recording.