The Trinity of Odissi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

View Entire Book

ORISSA REVIEW VOL. LXI NO. 12 JULY 2005 DIGAMBAR MOHANTY, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary BAISHNAB PRASAD MOHANTY Director-cum-Joint Secretary SASANKA SEKHAR PANDA Joint Director-cum-Deputy Secretary Editor BIBEKANANDA BISWAL Associate Editor Sadhana Mishra Editorial Assistance Manas R. Nayak Cover Design & Illustration Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Manoj Kumar Patro D.T.P. & Design The Orissa Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Orissa’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Orissa Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Orissa. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Orissa, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Orissa Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. E-mail : [email protected] Five Rupees / Copy Visit : www.orissagov.nic.in Fifty Rupees / Yearly Contact : Ph. 0674-2411839 CONTENTS Editorial Landlord Sri Jagannath Mahaprabhu Bije Puri Dr. Chitrasen Pasayat ... 1 Jamesvara Temple at Puri Ratnakar Mohapatra ... 6 Vedic Background of Jagannath Cult Dr. Bidyut Lata Ray ... 15 Orissan Vaisnavism Under Jagannath Cult Dr. Braja Kishore Swain ... 18 Bhakta Kabi Sri Bhakta Charan Das and His Work Somanath Jena ... 23 'Manobodha Chautisa' The Essence of Patriotism in Temple Multiplication - Dr. Braja Kishore Padhi ... 26 Kulada Jagannath Rani Suryamani Patamahadei : An Extraordinary Lady in Puri Temple Administration Prof. Jagannath Mohanty ... 30 Sri Ratnabhandar of Srimandir Dr. Janmejaya Choudhury ... 32 Lord Jagannath of Jaguleipatna Braja Paikray ... 34 Jainism and Buddhism in Jagannath Culture Pabitra Mohan Barik ... 36 Balabhadra Upasana and Tulasi Kshetra Er. -

Odissi Dance

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2005 ODISSI DANCE Photo Courtesy : Introduction : KNM Foundation, BBSR Odissi dance got its recognition as a classical dance, after Bharat Natyam, Kathak & Kathakali in the year 1958, although it had a glorious past. The temple like Konark have kept alive this ancient forms of dance in the stone-carved damsels with their unique lusture, posture and gesture. In the temple of Lord Jagannath it is the devadasis, who were performing this dance regularly before Lord Jagannath, the Lord of the Universe. After the introduction of the Gita Govinda, the love theme of Lordess Radha and Lord Krishna, the devadasis performed abhinaya with different Bhavas & Rasas. The Gotipua system of dance was performed by young boys dressed as girls. During the period of Ray Ramananda, the Governor of Raj Mahendri the Gotipua style was kept alive and attained popularity. The different items of the Odissi dance style are Mangalacharan, Batu Nrutya or Sthayi Nrutya, Pallavi, Abhinaya & Mokhya. Starting from Mangalacharan, it ends in Mokhya. The songs are based upon the writings of poets who adored Lordess Radha and Krishna, as their ISTHADEVA & DEVIS, above all KRUSHNA LILA or ŎRASALILAŏ are Banamali, Upendra Bhanja, Kabi Surya Baladev Rath, Gopal Krishna, Jayadev & Vidagdha Kavi Abhimanyu Samant Singhar. ODISSI DANCE RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE CLASSICAL DANCE FORM Press Comments :±08-04-58 STATESMAN őIt was fit occasion for Mrs. Indrani Rehman to dance on the very day on which the Sangeet Natak Akademy officially recognised Orissi dancing -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

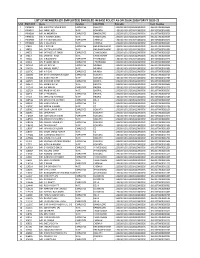

List of Members (Ex-Employee) Enrolled in Base Policy As on 11.05.2020 for Fy 2020-21

LIST OF MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEE) ENROLLED IN BASE POLICY AS ON 11.05.2020 FOR FY 2020-21 Sr. EMP No. LOCATION CODE Insured name Relation PolicyNo Card_Number 1 CO 00016G MS. REENA JHINGAN WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000103 2 CO 00016G MR. K K JHINGAN EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000126 3 DELHI 00030B MS. PRITPAL KAUR VIJ WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000203 4 DELHI 00030B MR. ANOOP SINGH VIJ EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000226 5 DELHI 00037K MS. ASHA RANI PURI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000303 6 DELHI 00037K MR. D D PURI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000326 7 DELHI 00041H MS. VIDYAWATI RANGRA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000403 8 DELHI 00041H MR. BIDHU RAM RANGRA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000426 9 AHMEDABAD 00042A MS. CHANDER TANEJA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000503 10 AHMEDABAD 00042A MR. VAS DEV TANEJA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000526 11 CO 00043D MS. LALTHANZAUVI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000603 12 CO 00043D MR. SAJEEVAN LAL EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000626 13 DELHI 00045L MR. SRI KRISHAN GANDHI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000726 14 CO 00050G MS. KANAK CHAUHAN WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000803 15 CO 00050G MR. K S CHAUHAN EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000826 16 DELHI 00051E MR. K K SACHDEVA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000000926 17 DELHI 00055H MS. SAROJ BALA NAGPAL WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001003 18 DELHI 00055H MR. VINOD KUMAR NAGPAL EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001026 19 CHANDIGARH 00064G MS. VEENA PURI WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001103 20 CHANDIGARH 00064G MR. V K PURI EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001126 21 CO 00065E MS. KAMLESH SHARMA WIFE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001203 22 CO 00065E MR. BADRI NATH SHARMA EMPLOYEE 130200/130132028120000030 0611070000001226 23 DELHI 00069H MS. -

LIST of MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEES) ENROLLED in BASE POLICY AS on 20.04.2020 for FY 2020-21 S.NO EMPCODE Name Relation LOCATION Policyno Card Number 1 PRMB22 MR

LIST OF MEMBERS (EX-EMPLOYEES) ENROLLED IN BASE POLICY AS ON 20.04.2020 FOR FY 2020-21 S.NO EMPCODE Name Relation LOCATION PolicyNo Card_Number 1 PRMB22 MR. SWAPAN KUMAR ROY EMPLOYEE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283626 2 PRMB22 MS. DIPALI ROY WIFE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283603 3 PRMB19 MR. M AKBARSHA EMPLOYEE BANGALORE :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283526 4 PRMB19 MS. A HAMIDA BANU WIFE BANGALORE :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283503 5 PRMB09 MR. T S VIJAYAKUMAR EMPLOYEE CHENNAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283426 6 PRMB09 MS. V KALAIVANI WIFE CHENNAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283403 7 14819J MR. P N PATRI EMPLOYEE BHUBANESHWAR :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283326 8 14819J MS. GEETANJALI PATRI WIFE BHUBANESHWAR :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283303 9 14027J MR. JATINDERJIT SINGH EMPLOYEE CHANDIGARH :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283226 10 14027J MS. JASWANT KAUR WIFE CHANDIGARH :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283203 11 13346J MS. D RAMADEVI EMPLOYEE HYDERABAD :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283126 12 13314L MS. P SABIRUNNISA EMPLOYEE HYDERABAD :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000283026 13 12435D MR. H C RAJPUT EMPLOYEE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282926 14 12435D MS. MANJU RAJPUT WIFE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282903 15 12363C MR. N R DAS EMPLOYEE MUMBAI :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282826 16 12358G MR. BHIM CHANDRA HALDER EMPLOYEE KOLKATA :130200/130132028120000030 :0611070000282726 -

International Journal of Scientific Research

ORIGINAL RESEARCH PAPER Volume-8 | Issue-6 | June-2019 | PRINT ISSN No. 2277 - 8179 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH USE AND APPLICATION OF ODISSI MUSIC IN GOTIPUA TRADITION Arts Bishnu Mohan Research Scholar, Utkal University Of Culture, Bhubaneswar Kabi ABSTRACT Odissi music is a unique style of Indian traditional music with all the modules of Indian classical form as like Carnatic and Hindustani. It is necessary to make this form of Indian music to prosper through proper study, revival, propagation, etc. This traditional style of music form is still survived through Odissi and Gotipua dance etc. The traditional music movement of Odisha has taken special drive for reaching at the zenith as like other traditional Indian classical music with traditional Odissi and Gotipua dance. Odissi music involves several genres of songs as well as performances that are structured and composed in different ways depending on the context and function of the performance. The Odissi music of today has evolved from the style of Gotipua music. It retains elements of both Mahari and Gotipua dance and also incorporates the allied art forms of Odisha closely associated with the great Jagannath cult. KEYWORDS GOTIPUA, DANCE, ODISSI, MUSIC Odissi as we know today reects a process of reconstruction that began musical ethos and bestow this rich legacy of Odissi classical music to after Independence. There are a number of musical instruments used to our successors. More seminars and workshops should be conducted accompany the Gotipua dance form of Odissi dance. As mentioned, emphasizing on the classicism of Odissi vocal and instrumental music . originally Odissi was sung to the dance of the Mahari/Devadasis at the The Odissi music is the characteristics of Udramagadhi style, one of Jagannath Temple, and was later sung to the dances by young boys, the signicant branches among Indian classical music forms. -

4.2.5 Saivism 90 Xn

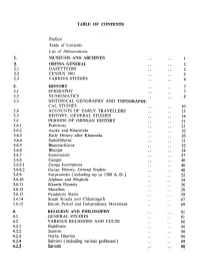

TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Table of Contents List of Abbreviations 1. MUSEUMS AND ARCHIVES 2. ORISSA, GENERAL 2 2.1 GAZETTEERS 2 2.2 CENSUS 1961 3 2.3 VARIOUS STUDIES 4 3. HISTORY 7 3.1 EPIGRAPHY 7 3.2 NUMISMATICS 8 3.3 HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY AND TOPOGRAPHI- CAL STUDIES 10 3.4 ACCOUNTS OF EARLY TRAVELLERS 13 3.5 HISTORY, GENERAL STUDIES 14 3.6 PERIODS OF ORISSAN HISTORY 21 3.6.1 Prehistory 21 3.6.2 Asoka and Kharavela 22 3.6.3 Early History after Kharavela 26 3.6.4 Sailodbhavas 31 3.6.5 Bhauma-Karas 32 3.6.6 Bhanjas 34 3.6.7 Somavamsis 37 3.6.8 Gangas 40 3.6.8.1 Ganga Inscriptions 40 3.6.8.2 Ganga History, General Studies 48 3.6.9 Suryavamsis (including up to 1568 A. D.) 52 3.6.10 Afghans and Moghuls 54 3.6.11 Khurda Dynasty 56 3.6.12 Marathas 58 3.6.13 Feudatory States 59 3.6.14 South Kosala and Chhattisgarh 67 3.6.15 British Period and Independence Movement 69 4. RELIGION AND PHILOSOPHY 81 4.1 GENERAL STUDIES 81 4.2 VARIOUS RELIGIONS AND CULTS 86 4.2.1 Buddhism 86 4.2.2 Jainism 4.2.3 Natha Dharma 4.2.4 Saktism (including various goddesses) 89 4.2.5 Saivism 90 xn 4.2.6 Surya Cult 91 4.2.7 Vaisnavism 92 4.2.8 Jagannatha Cult 94 4.2.9 Mahima Dharma 103 5. ART 104 5.1 GENERAL STUDIES 104 5.2 ARCHAEOLOGY ( Excavations ) 107 5.3 MONUMENTS, ARCHITECTURE 110 5.4 PLASTIC ART AND ICONOGRAPHY 118 5.5 PAINTING 122 5.6 INDUSTRIAL ART AND APPLIED ART 123 5.7 FOLK ART 124 5.8 DANCE AND MUSIC 125 6. -

Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty

Classical Status to Odia Language Odisha Review Medieval Odia Literature and Bhanja Dynasty Dr. Sarat Chandra Rath Medieval Odia literature is dated between 1650- as the thrill of divine laughter. Swami 1850. Akbar the Mughal emperor conquered Prangyanananda opined in his book ‘Historical Odisha in 1592. The suffering of the people during Development of Indian Music’ that music can be Aurangzeb (1658-1707) was intolerable. The said to be the sweet and soothing sounds that most sensitive issue was the destruction. Common vibrate and create an aesthetic feeling and beauties people were morally depressed, economically of the nature. Also he added ‘Music is recognized ruined and politically disturbed. After 1761, the as the greatest and finest art that brings permanent Bengal Nawabs ruled a portion of Odisha, but peace and solace to the human world’1. The poets the major part passed to the Marathas. Odisha of the medieval age could realize and recognize was occupied by the British in 1803. During this their poetic creation in the same vibrancy. Such period Odisha lost its freedom in the sphere of creation in Odisha carried a specific importance art and culture. At this juncture the Odia literature due to its musical excellency, which was hardly was in trauma. During this period extraordinary found at that time in any other neighbouring poets were Dinakrushna Das, Upendra Bhanja, language literature of Indo-Aryan family such as Bhupati Pandit Lokanath Bidyadhara. However Bengali and Assamese etc. at that time. This in the present context the literary contribution of implied the interest of people in music and song Bhanjasa, Balbhadra, Tribikram, Ghana, Upendra for their common entertainment. -

Odissi Dance) 2020 THREE YEAR FULL TIME PROGRAMME

Learning Outcome based Curriculum Framework (LOCF) For Undergraduate Programme B.P.A. (Odissi Dance) 2020 THREE YEAR FULL TIME PROGRAMME Syllabus and Scheme of Examination This shall be applicable for students seeking admission in B.P.A. Odissi Dance Programme in 2020-2021 DEPARTMENT OF PERFORMING ARTS Faculty of Indic Studies Sri Sri University DPA-B.P.A. (O.D.) Page 0 Introduction – The proposed programme shall be conducted and supervised by the Faculty of Indic Studies, Department of Performing Arts, Sri Sri University, Cuttack (Odisha). This programme has been designed on the Learning Outcomes Curriculum Framework (LOCF) under UGC guidelines, offers flexibility within the structure of the programme while ensuring the strong foundation and in-depth knowledge of the discipline. The learning outcome-based curriculum ensures its suitability in the present day needs of the student towards higher education and employment. The Department of Performing Arts at Sri Sri University is now offering bachelor degree program with specialization in Performing Arts (Odissi Dance and Hindustani Vocal Music) Vision – The Department of Performing Arts aims to impart holistic education to equip future artistes to achieve the highest levels of professional ability, in a learning atmosphere that fosters universal human values through the Performing Arts. To preserve, perpetuate and monumentalize through the Guru-Sishya Parampara (teacher-disciple tradition) the classical performing arts in their essence of beauty, harmony and spiritual evolution, giving scope for innovation and continuity with change to suit modern ethos. Mission : To be a center of excellence in performing arts by harnessing puritan skills from Vedic days to modern times and creating artistic expressions through learned human ingenuity of emerging times for furtherance of societal interest in the visual & performing arts. -

Minutes of 32Nd Meeting of the Cultural

1 F.No. 9-1/2016-S&F Government of India Ministry of Culture **** Puratatav Bhavan, 2nd Floor ‘D’ Block, GPO Complex, INA, New Delhi-110023 Dated: 30.11.2016 MINUTES OF 32nd MEETING OF CULTURAL FUNCTIONS AND PRODUCTION GRANT SCHEME (CFPGS) HELD ON 7TH AND 8TH MAY, 2016 (INDIVIDUALS CAPACITY) and 26TH TO 28TH AUGUST, 2016 AT NCZCC, ALLAHABAD Under CFPGS Scheme Financial Assistance is given to ‘Not-for-Profit’ Organisations, NGOs includ ing Soc iet ies, T rust, Univ ersit ies and Ind iv id ua ls for ho ld ing Conferences, Seminar, Workshops, Festivals, Exhibitions, Production of Dance, Drama-Theatre, Music and undertaking small research projects etc. on any art forms/important cultural matters relating to different aspects of Indian Culture. The quantum of assistance is restricted to 75% of the project cost subject to maximum of Rs. 5 Lakhs per project as recommend by the Expert Committee. In exceptional circumstances Financial Assistance may be given upto Rs. 20 Lakhs with the approval of Hon’ble Minister of Culture. CASE – I: 1. A meeting of CFPGS was held on 7 th and 8th May, 2016 under the Chairmanship of Shri K. K. Mittal, Additional Secretary to consider the individual proposals for financial assistance by the Expert Committee. 2. The Expert Committee meeting was attended by the following:- (i) Shri K.K. Mittal, Additional Secretary, Chairman (ii) Shri M.L. Srivastava, Joint Secretary, Member (iii) Shri G.K. Bansal, Director, NCZCC, Allahabad, Member (iv ) Dr. Om Prakash Bharti, Director, EZCC, Kolkata, Member, (v) Dr. Sajith E.N., Director, SZCC, Thanjavur, Member (v i) Shri Babu Rajan, DS , Sahitya Akademi , Member (v ii) Shri Santanu Bose, Dean, NSD, Member (viii) Shri Rajesh Sharma, Supervisor, LKA, Member (ix ) Shri Pradeep Kumar, Director, MOC, Member- Secretary 3. -

A Musical Fair

- J 2 . T was no different from other music MUSIC FESTIVAL people realised the benefits of punc festivals that Bombay is treated to tuality.” It was decided that those who during the peak music season, except I came first would get the better seats in that it was organised by Protima Bedi, A their block. “I wanted to train the and her Odissi Dance Centre students. audience to be on time,” explains Pro And since Protima is a commercial Musical tima. Unfortunately, the earliest arriv- password when it comes to all things ers took to the first few rows, which cultural, the festival drew to its had been reserved for VIPs—like V.P. charmed circle, big names. As a result, Fair Sathe, Minister of Information & contrary to a few thousand rupees that Broadcasting, Frank Simoes, who in a more modest organisation would cidentally took a load off the organis collect on such an occasion, Protima’s ers’ shoulders by collecting all the rough estimate stood at Rs 2 lakh. “We advertisements for the brochure and had aimed at about Rs 5 lakh. Let’s surprisingly enough, Kabir Bedi. Bedi, see—maybe some more contributions who sat in the third row, was easily one will come in,” says a disappointed head taller than the rest of the audience Protima. forcing the luckless spectators behind The proceeds are to go towards the him to crane their necks. At the end Odissi Dance Centre, initiated two everyone had been seated to his years ago to “celebrate, preserve and satisfaction and the session was 45 perpetuate” Odissi, which as a dance minutes behind schedule.