Module 1 Dance in India Today an Overview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How Modern India Reinvented Classical Dance

ESSAY espite considerable material progress, they have had to dispense with many aspects of the the world still views India as an glorious tradition that had been built up over several ancient land steeped in spirituality, centuries. The arrival of the Western proscenium stage with a culture that stretches back to in India and the setting up of modern auditoria altered a hoary, unfathomable past. Indians, the landscape of the performing arts so radically that too, subscribe to this glorification of all forms had to revamp their presentation protocols to its timelessness and have been encouraged, especially survive. The stone or tiled floor of temples and palaces Din the last few years, to take an obsessive pride in this was, for instance, replaced by the wooden floor of tryst with eternity. Thus, we can hardly be faulted in the proscenium stage, and those that had an element subscribing to very marketable propositions, like the of cushioning gave an ‘extra bounce’, which dancers one that claims our classical dance forms represent learnt to utilise. Dancers also had to reorient their steps an unbroken tradition for several millennia and all of and postures as their audience was no more seated all them go back to the venerable sage, Bharata Muni, who around them, as in temples or palaces of the past, but in composed Natyashastra. No one, however, is sure when front, in much larger numbers than ever before. Similarly, he lived or wrote this treatise on dance and theatre. while microphones and better acoustics management, Estimates range from 500 BC to 500 AD, which is a coupled with new lighting technologies, did help rather long stretch of time, though pragmatists often classical music and dance a lot, they also demanded re- settle for a shorter time band, 200 BC to 200 AD. -

Indian Cultural Troupes As Part of Namaste Russia 2019

Jawaharlal Nehru Cultural Center Embassy of India Moscow – 2019 – With a view to promote and further strengthen cultural ties between India and Russia, cultural troupes of both countries visited each others’ country for performances. In 2018, three groups from Russia – ‘Reverse’ Musical theater production by Moscow Musical Theater, Quintet ‘Timofei Dokshizer New Life Brass’ and Vainakh Chechen State Dance Ensemble – visited India. These groups gave enthralling performances in New Delhi, Chennai, Jaipur, Chandigarh, Kolkata and Hyderabad. People of India got the opportunity to witness their performances. Similarly, four Indian groups - ‘Drishtikon’. a Kathak Dance Group, Hindustani Kalari Sangam, a martial art group, Bollywood Dance Group and Shehnai Group visited Russia. These groups performed in Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, Veliky Novgorod, Saint Petersburg, Moscow, Sochi, Krasnodar, Gelendzhik, Yessentuki and Kislovodsk. Indian groups gave spectacular performances that were highly appreciated by the Russian audiences. ***** Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company – the Drishtikon Dance Foundation, a group of Indian Classical Dance and Contemporary dance based on Kathak, was established with a vision to look at tradition with a modern mind, to explore the past to create a new imaginative future. The dance company aims to achieve excellence and virtuosity in the rich classical Indian dance form of kathak, as well as encourage the spirit of innovation. In doing so, Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company seeks to challenge established norms and develop the courage to dance their own dance, while at the same time being informed about the heritage, cultures, influences and language of other dance styles and forms, viewpoints and ideas. Aditi Mangaldas is a leading dancer and choreographer in the classical Indian dance form of Kathak. -

Part 05.Indd

PART MISCELLANEOUS 5 TOPICS Awards and Honours Y NATIONAL AWARDS NATIONAL COMMUNAL Mohd. Hanif Khan Shastri and the HARMONY AWARDS 2009 Center for Human Rights and Social (announced in January 2010) Welfare, Rajasthan MOORTI DEVI AWARD Union law Minister Verrappa Moily KOYA NATIONAL JOURNALISM A G Noorani and NDTV Group AWARD 2009 Editor Barkha Dutt. LAL BAHADUR SHASTRI Sunil Mittal AWARD 2009 KALINGA PRIZE (UNESCO’S) Renowned scientist Yash Pal jointly with Prof Trinh Xuan Thuan of Vietnam RAJIV GANDHI NATIONAL GAIL (India) for the large scale QUALITY AWARD manufacturing industries category OLOF PLAME PRIZE 2009 Carsten Jensen NAYUDAMMA AWARD 2009 V. K. Saraswat MALCOLM ADISESHIAH Dr C.P. Chandrasekhar of Centre AWARD 2009 for Economic Studies and Planning, School of Social Sciences, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi. INDU SHARMA KATHA SAMMAN Mr Mohan Rana and Mr Bhagwan AWARD 2009 Dass Morwal PHALKE RATAN AWARD 2009 Actor Manoj Kumar SHANTI SWARUP BHATNAGAR Charusita Chakravarti – IIT Delhi, AWARDS 2008-2009 Santosh G. Honavar – L.V. Prasad Eye Institute; S.K. Satheesh –Indian Institute of Science; Amitabh Joshi and Bhaskar Shah – Biological Science; Giridhar Madras and Jayant Ramaswamy Harsita – Eengineering Science; R. Gopakumar and A. Dhar- Physical Science; Narayanswamy Jayraman – Chemical Science, and Verapally Suresh – Mathematical Science. NATIONAL MINORITY RIGHTS MM Tirmizi, advocate – Gujarat AWARD 2009 High Court 55th Filmfare Awards Best Actor (Male) Amitabh Bachchan–Paa; (Female) Vidya Balan–Paa Best Film 3 Idiots; Best Director Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots; Best Story Abhijat Joshi, Rajkumar Hirani–3 Idiots Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Male) Boman Irani–3 Idiots; (Female) Kalki Koechlin–Dev D Best Screenplay Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra, Abhijat Joshi–3 Idiots; Best Choreography Bosco-Caesar–Chor Bazaari Love Aaj Kal Best Dialogue Rajkumar Hirani, Vidhu Vinod Chopra–3 idiots Best Cinematography Rajeev Rai–Dev D Life- time Achievement Award Shashi Kapoor–Khayyam R D Burman Music Award Amit Tivedi. -

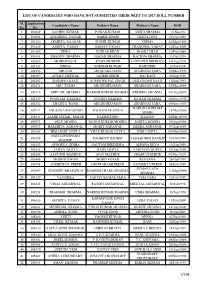

List of Candidates Who Have Not Submitted Their Neet Ug 2017 Roll Number

LIST OF CANDIDATES WHO HAVE NOT SUBMITTED THEIR NEET UG 2017 ROLL NUMBER Sl. Application Candidate's Name Father's Name Mother's Name DOB No. No. 1 100249 SACHIN KUMAR PAWAN KUMAR ANITA SHARMA 15.Nov.93 2 100808 ANUSHEEL NAGAR OMBIR SINGH GEETA DEVI 07/Oct/1998 3 101222 AKSHITA DAAGAR SUSHIL KUMAR SEEMA 24/May/1999 4 101469 ANKITA YADAV SANJAY YADAV CHANCHAL YADAV 31/Dec/1999 5 101593 ZEWA NAWAB KHAN NOOR JAHAN 10/Feb/1999 6 101814 SHAGUN SHARMA GAGAN SHARMA RACHNA SHARMA 13/Oct/1998 7 102087 MOHD FAISAL SHAHABUDDIN JANNATUL FIRDOUS 14/Aug/1998 8 102121 SNEHA SOBODH KUMAR RAJENDRI 20/Jul/1998 9 102256 ABUZAR MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 10 102397 ANJALI DESWAL JAGBIR SINGH RAJ RANI 05/Sep/1998 11 102402 RASMEET KAUR SURINDER PAL SINGH GURVINDER KAUR 11/Sep/1997 12 102474 ABU TALHA MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 25/Mar/1999 13 102515 SHIVANI SHARMA RAKESH KUMAR SHARMA KRISHNA SHARMA 01/Aug/2000 14 102529 POONAM SHARMA GOVIND SHARMA RAJESH SHARMA 04/Nov/1998 15 102532 SHAISTA BANO MD SHAHZAMAN SHABNAM SABA 09/Nov/1997 KARUNA KUMARI 16 102711 ANUSHKA RAJ SINGH RAJ KUMAR SINGH 12/Mar/2000 SINGH 17 102841 AAMIR SUHAIL MALIK NASIMUDDIN SHANNO 26/May/1996 18 102971 ABLE MOGHA MANOJ KUMAR MOGHA SARITA MOGHA 19/Aug/1998 19 103053 HARSHITA AGRAWAL MOHIT AGRAWAL MEERA AGRAWAL 07/Sep/1999 20 103245 HIMANSHI GUPTA VIJAY KUMAR GUPTA INDU GUPTA 09/May/2000 NGULLIENTHANG 21 103428 PAOKHUP HAOKIP VANKHOMOI HAOKIP 03/Oct/1998 HAOKIP 22 103433 APOORVA SINHA GAUTAM BIRENDRA ALPANA DEVA 12/Sep/1999 23 103518 TANYA GUPTA RAJIV GUPTA VANDANA GUPTA 29/Apr/1999 -

Odissi Dance

ORISSA REFERENCE ANNUAL - 2005 ODISSI DANCE Photo Courtesy : Introduction : KNM Foundation, BBSR Odissi dance got its recognition as a classical dance, after Bharat Natyam, Kathak & Kathakali in the year 1958, although it had a glorious past. The temple like Konark have kept alive this ancient forms of dance in the stone-carved damsels with their unique lusture, posture and gesture. In the temple of Lord Jagannath it is the devadasis, who were performing this dance regularly before Lord Jagannath, the Lord of the Universe. After the introduction of the Gita Govinda, the love theme of Lordess Radha and Lord Krishna, the devadasis performed abhinaya with different Bhavas & Rasas. The Gotipua system of dance was performed by young boys dressed as girls. During the period of Ray Ramananda, the Governor of Raj Mahendri the Gotipua style was kept alive and attained popularity. The different items of the Odissi dance style are Mangalacharan, Batu Nrutya or Sthayi Nrutya, Pallavi, Abhinaya & Mokhya. Starting from Mangalacharan, it ends in Mokhya. The songs are based upon the writings of poets who adored Lordess Radha and Krishna, as their ISTHADEVA & DEVIS, above all KRUSHNA LILA or ŎRASALILAŏ are Banamali, Upendra Bhanja, Kabi Surya Baladev Rath, Gopal Krishna, Jayadev & Vidagdha Kavi Abhimanyu Samant Singhar. ODISSI DANCE RECOGNISED AS ONE OF THE CLASSICAL DANCE FORM Press Comments :±08-04-58 STATESMAN őIt was fit occasion for Mrs. Indrani Rehman to dance on the very day on which the Sangeet Natak Akademy officially recognised Orissi dancing -

Odisha Review

ODISHA REVIEW VOL. LXXI NO. 2-3 SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER - 2014 MADHUSUDAN PADHI, I.A.S. Commissioner-cum-Secretary BHAGABAN NANDA, O.A.S, ( SAG) Special Secretary DR. LENIN MOHANTY Editor Editorial Assistance Production Assistance Bibhu Chandra Mishra Debasis Pattnaik Bikram Maharana Sadhana Mishra Cover Design & Illustration D.T.P. & Design Manas Ranjan Nayak Hemanta Kumar Sahoo Photo Raju Singh Manoranjan Mohanty The Odisha Review aims at disseminating knowledge and information concerning Odisha’s socio-economic development, art and culture. Views, records, statistics and information published in the Odisha Review are not necessarily those of the Government of Odisha. Published by Information & Public Relations Department, Government of Odisha, Bhubaneswar - 751001 and Printed at Odisha Government Press, Cuttack - 753010. For subscription and trade inquiry, please contact : Manager, Publications, Information & Public Relations Department, Loksampark Bhawan, Bhubaneswar - 751001. Five Rupees / Copy E-mail : [email protected] Visit : http://odisha.gov.in Contact : 9937057528(M) CONTENTS Nabakalebar Bhagaban Mahapatra ... 1 Good Governance ... 5 The Concept of Sakti and Its Appearance in Odisha Sanjaya Kumar Mahapatra ... 8 Siva and Shakti Cult in Parlakhemundi : Some Reflections Dr. N.P. Panigrahi ... 11 Durga Temple at Ambapara : A Study on Art and Architecture Dr. Ratnakar Mohapatra ... 20 Perspective of a Teacher as Nation Builder Dr. Manoranjan Pradhan ... 22 A Macroscopic View of Indian Education System Lopamudra Pradhan ... 27 Abhaya Kumar Panda The Immortal Star of Suando Parikshit Mishra ... 42 Consumer is the King Under the Consumer Protection Law Prof. Hrudaya Ballav Das ... 45 Paradigm of Socio-Economic-Cultural Notion in Colonial Odisha : Contemplation of Gopabandhu Das Snigdha Acharya ... 48 Raghunath Panigrahy : The Genius Bhaskar Parichha .. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Current Awareness Bulletin

No.1 January 2016 Current Awareness Bulletin Centre for Women’s Development Studies 25, Bhai Vir Singh Marg (Gole Market), New Delhi-110001, India. Ph.: 011-32226930, 32226931 Fax: 91-23346044 E-mail: [email protected] | URL: www.cwds.ac.in/library/library.htm i CONTENTS Section 1: Journals/ Periodicals/ Newsletters Articles Arts .................................................................................. 001 Child Abuse ..................................................................... 002-004 Child Labour .................................................................... 005 Child Marriage ................................................................. 006- 007 Children ........................................................................... 008-024 Children’s Rights ............................................................. 025-026 Crimes ............................................................................. 027 Demography .................................................................... 028-037 Education ......................................................................... 038-040 Employment ..................................................................... 041-048 Family .............................................................................. 049 Family Planning ............................................................... 050-051 Feminism ......................................................................... 052 Gender Studies ................................................................ -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

10U/111121 (To Bejilled up by the Candidate by Blue/Black Ball-Point Pen)

Question Booklet No. 10U/111121 (To bejilled up by the candidate by blue/black ball-point pen) Roll No. LI_..L._.L..._L.-..JL--'_....l._....L_.J Roll No. (Write the digits in words) ............................................................................................... .. Serial No. of Answer Sheet .............................................. D~'y and Date ................................................................... ( Signature of Invigilator) INSTRUCTIONS TO CANDIDATES (Use only bluelblack ball-point pen in the space above and on both sides of the Answer Sheet) 1. Within 10 minutes of the issue of the Question Booklet, check the Question Booklet to ensure that it contains all the pages in correct sequence and that no page/question is missing. In case of faulty Question Booklet bring it to the notice oflhe Superintendentllnvigilators immediately to obtain a fresh Question Booklet. 2. Do not bring any loose paper, written or blank, inside the Examination Hall except the Admit Card without its envelope, .\. A separate Answer Sheet b,' given. It !J'hould not he folded or mutilated A second Answer Sheet shall not be provided. Only the Answer Sheet will be evaluated 4. Write your Roll Number and Serial Number oflhe Answer Sheet by pen in the space prvided above. 5. On the front page ofthe Answer Sheet, write hy pen your Roll Numher in the space provided at the top and hy darkening the circles at the bottom. AI!J'o, wherever applicahle, write the Question Booklet Numher and the Set Numher in appropriate places. 6. No overwriting is allowed in the entries of Roll No., Question Booklet no. and Set no. (if any) on OMR sheet and Roll No. -

Name of the Artist & Contact Details Links Grading

MINISTRY OF CULTURE FESTIVAL OF INDIA CELL PANEL OF ARTISTS/GROUPS FOR PARTICIPATION IN FESTIVALS OF INDIA ABROAD (O - OUTSTANDING, P- PROMISING, W- WAITING) Kathak S.NO Name of the Artist & contact Details Links Grading 1. Arijeet Mukherjee Business Development and Events Coordinator https://vimeo.com/151495589 Aditi Mangaldas Dance Company - The Drishtikon Dance Foundation Password: within123 O ADD: N-75/4/2, Sainik Farms South Lane - W 17 (Main) New Delhi-110080 MOB: 0 93111 57771 | 0 98105 66044 http://vimeo.com/aditimangaldasdance/ WEB: www.aditimangaldasdance.com Email: unchartedseas [email protected] Password: AMDC-US 2 Shovana Narayan IA&AS retd https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hha O Kathak Guru(Padmashri& central Sangeet Natak Akademi awardee) Mq0Nxg5s T2-LL-103, Commonwealth Games Village, Delhi-110092 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eOD Cell:+919811173734+919810725340 RnwLc9Mg Email:[email protected] or [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAw Padmashree Awardee (1996) jM9ggTh8 SNA Awardee (1999-2000) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lsUd IJI0yn8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aR W89rFJ6dc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KAw jM9ggTh8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UN A_4Cf1taQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4Ax MxNkuxvw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RhL 6wQ1Y-WA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7A3 dh8pBElg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8Xe RJqb65e4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjsl5 Rq3HVo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJQ pWVKMTJI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xjsl5 Rq3HVo https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5Uf sLeqIYhY https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o- ftl8rIjnc https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jrnt MQy2320 https://i.ytimg.com/vi/IMKCvbQ7cUk/mq default.jpg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MS wixkNxubg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oO1 -WsLotZg https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gZrd 14SjJkA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RJq PTQTD-Zs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=PG5 -DTTykdk https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VW Fuv9mBUQI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1UY NfMqZ9aQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SDq xUHbTLHw 3. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ