Paper 18 History of Odisha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bargarh District

Orissa Review (Census Special) BARGARH DISTRICT Bargarh is a district on the Western border of The district of Bargarh is one of the newly Orissa. Prior to 1992, it was a subdivision of created districts carved out of the old Sambalpur Sambalpur district. Bargarh has been named after district. It has a population of 13.5 lakh of which the headquarters town Bargarh situated on the 50.62 percent are males and 49.38 percent left bank of the Jira river. The town is on the females. The area of the district is 5837 sq. Km National Highway No.6 and located at 59 km to and thus density is 231 per sq.km. The population the west of Sambalpur district. It is also served growth is 1.15 annually averaged over the decade by the D.B.K railway running from Jharsuguda of 1991-2001. Urban population of the district to Titlagarh. The railway station is about 3 kms constitute 7.69 percent of total population. The off the town. A meter gauge railway line connects Scheduled Caste population is 19.37 percent of Bargarh with the limestone quarry at Dunguri. The total population and major caste group are Ganda main Hirakud canal passes through the town and (54.82), Dewar (17.08) and Dhoba etc. (6.43 is known as the Bargarh canal. percent) among the Scheduled Castes. Similarly The District of Bargarh lies between the Scheduled Tribe population is 19.36 percent 200 45’ N to 210 45’N latitude and 820 40’E to of total and major Tribes groups of the total Tribes 830 50’E longitude. -

Q U Alificatio N C O Lleg E U N Iversity Year D Esig N Atio N D Ep Artmen T N Ame O F Th E in Stitu Tio N F Ro M D D /MM/Y Y

Faculty Profile, MKCG Medical College & Hospital, Berhampur Details of teaching experience (designations / Promotions / Transfers / Qualification Resignations / Joining) Name Sl. No. Sl. As ……… As year Department College University Institution Department Name of theof Name Designation Qualification Present DesignationPresent Present DesignationPresent Date of Joiningofthe in Date Joiningofthe in Date ToDD/MM/YYY FromDD/MM/YYY Present institution ………institution Present yearsand months Totalexperience in Name of the Department : ANAESTHESIOLOGY SCB MC, SCB MC, Utkal Anaesthesi Cuttack 14.12.1995 26.10.1998 M.B.B.S. 1987 Tutor / Lecturer 7 Years Cuttack University ology SVPPGIP, 27.10.1998 27.08.2002 Cuttack SCB MC, Cuttack 28.08.2002 04.06.2004 SCB MC, Utkal Assistant Anaesthesi M.D. / M.S. ( ) 1993 VSS MC, 08.09.2004 10.10.2006 6 Years Cuttack University Professor ology Burla Anaesthesi 28.12.2016 as 11.10.2006 24.07.2008 1 Dr. Laxmidhar Dash Professor 14.12.2012 SCB MC, ology Professor Cuttack Associate Anaesthesi SCB MC, D.M / M.Ch 25.07.2008 13.12.2012 4 Years Professor ology Cuttack VSS MC, Burla 14.12.2012 10.07.2015 Anaesthesi 5 Years 7 Professor SCB MC, 11.07.2015 25.02.2016 ology Months Cuttack 28.12.2016 Continuing MKCG MC, Bam VSS MC, Burla 21.12.1995 12.01.1999 SCB MC, Utkal Anaesthesi 7 Years 3 M.B.B.S. 1989 Tutor / Lecturer SCB MC, 19.01.1999 16.09.2002 Cuttack University ology Months Cuttack 17.09.2002 22.06.2005 SVPPGIP, Cuttack Anaesthesi 11.11.2016 as SCB MC, Utkal Assistant Anaesthesi SCB MC, 6 Years 3 2 Dr. -

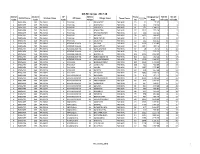

6Th MI Census 2017-18

6th MI Census 2017-18 District Stratum GP EARAS Thana Geographical 5th MI 6th MI District Name Stratum Name GP Name Village Name Thana Name H_S_No Code Code Code Village No Area Vill Code Vill Code 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 1 PAIKMAL 1 DANDAPAT PAIKMAL 59 29 72.39 1 1 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 1 PAIKMAL 2 DURGAPALI PAIKMAL 60 125 192.01 2 2 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 1 PAIKMAL 3 JARJAGAD PAIKMAL 61 672 1398.14 3 3 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 1 PAIKMAL 4 KOKANORA PAIKMAL 57 1313 993.26 5 5 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 1 PAIKMAL 5 KHANDIJHARAN PAIKMAL 62 456 515.25 6 6 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 1 PAIKMAL 6 PAIKMAL PAIKMAL 58 1052 889.95 9 9 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 1 PAIKMAL 7 RANJITAPUR PAIKMAL 74 621 1492.32 10 10 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 1 PAIKMAL 8 SALHEPALI PAIKMAL 63 665 831.65 11 11 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 2 KEREMELIBAHAL 9 BIJADIHI PAIKMAL 96 1403 1353.89 12 12 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 2 KEREMELIBAHAL 10 BHAGATPUR PAIKMAL 101 1051 908.14 13 13 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 2 KEREMELIBAHAL 11 DENGLIKENDU PAIKMAL 97 68 70.72 14 14 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 2 KEREMELIBAHAL 12 GANDAPALI PAIKMAL 99 721 592.24 15 15 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 2 KEREMELIBAHAL 13 HARIDATAL PAIKMAL 104 1389 2454.20 16 16 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 2 KEREMELIBAHAL 14 KEREMELIBAHAL PAIKMAL 103 621 362.21 17 17 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 2 KEREMELIBAHAL 15 KHANDASIBANJHI PAIKMAL 98 1348 1046.42 18 18 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 3 PALSADA 16 BUDHASAMBAR PAIKMAL 102 1244 1728.40 19 19 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 3 PALSADA 17 GOIBAHALI PAIKMAL 100 420 432.69 20 20 4 BARGARH 269 PAIKMAL 3 PALSADA 18 KHAIRA PAIKMAL 95 1687 1375.88 21 21 4 BARGARH -

Details of Para Legal Volunteers of District Legal Services Authority, Angul

DETAILS OF PARA LEGAL VOLUNTEERS OF DISTRICT LEGAL SERVICES AUTHORITY, ANGUL Sl No. Name of the PLV Age Gender Mobile Number Date of Empanelled in empanelment DLSA/ TLSC 1 Kausalya Muduli 38 Years Female 8658299890 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 2 Abanti Muduli 31 Years Female 8018391319 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 3 Jhunubala Sahu 38 Years Female 8018850439 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 4 Bijayeeni Sahu 44 Years Female 8658918552 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul Sarmistha Biswal 38 Years Female 9776454333 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 5 Sanghamitra Naik 23 Years Female 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 6 9556512700 Bikash Sasmal 23 Years Male 7077020304 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 7 Subhadra Sethi 29 Years Female 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 8 9348910431 9 Bibhu Charan Sahoo 40 Years Male 7894478755 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 10 Dipun Kumar Barik 25 Years Male 9938689679 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 11 Gopabandhu Naik 23 Years Male 7894548938 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 12 Puspanjali Pal 44 Years Female 9438072036 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul Jagannath Sahoo, Jagyaseni 45 Years Transgender 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 13 7894323217 Kinar 14 Kunirani Roul 58 Years Female 9078128575 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 15 Jhilli Behera 38 Years Female 9777916411 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 16 Bharati Garanaik 54 Years Female 9556529612 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul Dr. Satya Narayan Singh 60 Years Male 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 17 9853163931 Samant 18 Manasi Samal 37 Years Female 7504852540 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 19 Alekha Pradhan 36 Years Male 9337192960 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 20 Sita Pradhan 39 Years Female 9178409067 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 21 Puspalata Pradhan 34 Years Female 9078491627 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 22 Santilata Sahu 58 Years Female 9438327375 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul Askara sahoo 45 Years Female 8280417749 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 23 24 Bisikesan Naik 48 Years Male 8658400859 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 25 Ashok Kumar Pradhan 41 Years Male 9439349301 01.01.2021 DLSA, Angul 26 Prafulla Ch. -

Citizen Forum of WODC

DATA WODC SINCE INCEPTION TILL 05.08.2016 Project Released Sl No ID DISTRICT Executing Agency Name of the Project Amount Year Completion of Bauribandha Check Dam & Retaining Wall B.D.O., at Angapada, Angapada G.P. of 1 20350 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bridge Between Budiabahal to Majurkachheni, B.D.O., Kadalimunda G.P. of 2 20238 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Constn. of Main Building Ambapal Homeopathy B.D.O., Dispensary, Ambapal G. P. of 3 20345 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 500000 2014-2015 Completion of Addl. Class Room of Lunahandi High School Building, Lunahandi 4 19664 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. G.P. of Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Constn. of Gudighara Bhagabat Tungi at Tentheipali, Kudagaon G.P. of 5 19264 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Constn. of Kothaghara at Tentheipali, Kudagaon G.P. of 6 19265 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. Athmallik Block 300000 2014-2015 Completion of Building and Water Supply to Radhakrishna High School, B.D.O., Pursmala, Urukula G.P. of 7 19020 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 700000 2014-2015 Completion of Pitabaligorada B.D.O., Bridge, Urukula G.P. of 8 19019 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Kishorenagar Block 900000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bridge at Ghaginallah in between Ghanpur Serenda Road, B.D.O., Urukula G.P. of Kishorenagar 9 19018 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR. Block 1000000 2014-2015 Completion of Kalyan Mandap at Routpada, Kandhapada G.P. 10 19656 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. of Athmallik Block 200000 2014-2015 Constn. of Bhoga Mandap inside Maheswari Temple of 11 19659 ANGUL B.D.O., ATHMALLIK. -

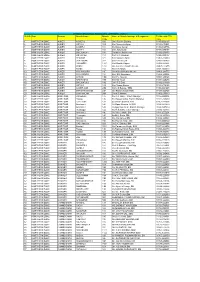

BO GRO LIST UPDATED 20-21-Without Email Id.Xlsx

BRANCH GRIEVANCE REDRESSAL OFFICERS : 2020-21 SL NO Zone Division Branch Name Branch Name of Branch Incharge & Designation Tel No. with STD Code code 1 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER AJMER-2 106 Shri Rajeev Sharma 0145-2662465 2 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KOTA-2 109 Shri Prameet billiyan 0744-2473051 3 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER AJMER-1 181 Sh. Manoj Kumar 0145-2429756 4 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KOTA-1 182 Shri Ajay Goyal 0744-2390457 5 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BHILWARA-1 198 Shri khem Raj Meena 01482-239838 6 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KOTA-CAB 313 Shri K C Mahavar 0744-2390797 7 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BEAWAR 321 Shri Kailash Chand 01462-225039 8 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER JHALAWAR 322 Shri B R Meena 07432-232433 9 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER LAKHAERI 1201 Shri Manish Kapoor 07438-261681 10 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KEKRI 1202 SH. Suresh Chandra Meena 01467-222475 11 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BUNDI 18A Shri V D Singh 0747-2456620 12 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KISHANGARH 18F Shri Kailash Kumar Meena 01463-246775 13 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER SHAHAPURA 18J Shri S K Srivastava 01482-223564 14 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BARAN 18M Shri P L Meena 07453-230165 15 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER NASIRABAD 18N Shri AD Tiwari 01491-220273 16 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BHILWARA-2 18U Shri R D Dad 01482-243199 17 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER KOTA-3 18X Shri Pawan Kumar 0744-2472423 18 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER AJMER CAB 29N Shri J N Bairwa / SBM 0145-2664665 19 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BHAWANI MANDI 29P shri Rajesh Kumar Rathi 07433-222725 20 NORTHERN ZONE AJMER BIJAYNAGAR 29R Shri K.S.Meena 01462-230149 21 NORTHERN ZONE AMRITSAR Pathankot-I 135 Sh. -

ODISHA:CUTTACK NOTIFICATION No:-444(Syllabus)/ Date:-14.07.2017

OFFICE OF THE BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION :ODISHA:CUTTACK NOTIFICATION No:-444(syllabus)/ Date:-14.07.2017 IV-B/35/2017 In pursuance of the Notification No-19724/SME, Dated-28.09.2016 of the Govt. of Odisha, School & Mass Education Deptt. & Letter No-1038/Plg, Dated-19.06.2017 of the State Project Director, OMSM/RMSA, the Vocational Education Course under RMSA at Secondary School Level in Trades i.e. 1.IT & ITES, 2.Travel & Tourism , 3.Retail & 4.BFSI will be introduced for Class-X(Level-2) from the Academic Session-2017-18 as compulsory subject in the following 208 selected Schools (Subject mentioned against each).The above subjects shall be the alternative of the existing 3rd language subjects . The students may Opt. either one of the Third Languages or Vocational subject as per their choice. The period of distribution shall be as that of Third Language Subjects i.e. 04 period per week so as to complete 200 hours of course of Level-2. The course curriculum shall be at par with the curriculum offered by PSSCIVE, Bhopal . List of 208 schools (178 + 30) approved under Vocational Education (2017-18) under RMSA . Sl. Name of the Approval Name of Schools UDISE Code Trade 1 Trade 2 No. District Phase PANCHAGARH BIJAY K. HS, 1 ANGUL 21150303103 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism BANARPAL 2 ANGUL CHHENDIPADA High School 21150405104 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 3 ANGUL KISHORENAGAR High School 21150606501 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism MAHENDRA High School, 4 ANGUL 21151001201 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism ATHAMALLIK 5 ANGUL MAHATAB High School 21150718201 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 6 ANGUL PABITRA MOHAN High School 21150516502 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 7 ANGUL JUBARAJ High School 21151101303 Phase II IT/ITeS Travel & Tourism 8 ANGUL Anugul High School 21150902201 Phase I IT/ITeS 9 BALANGIR GOVT. -

Odisha Review Dr

Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 Index of Orissa Review (April-1948 to May -2013) Sl. Title of the Article Name of the Author Page No. No April - 1948 1. The Country Side : Its Needs, Drawbacks and Opportunities (Extracts from Speeches of H.E. Dr. K.N. Katju ) ... 1 2. Gur from Palm-Juice ... 5 3. Facilities and Amenities ... 6 4. Departmental Tit-Bits ... 8 5. In State Areas ... 12 6. Development Notes ... 13 7. Food News ... 17 8. The Draft Constitution of India ... 20 9. The Honourable Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru's Visit to Orissa ... 22 10. New Capital for Orissa ... 33 11. The Hirakud Project ... 34 12. Fuller Report of Speeches ... 37 May - 1948 1. Opportunities of United Development ... 43 2. Implication of the Union (Speeches of Hon'ble Prime Minister) ... 47 3. The Orissa State's Assembly ... 49 4. Policies and Decisions ... 50 5. Implications of a Secular State ... 52 6. Laws Passed or Proposed ... 54 7. Facilities & Amenities ... 61 8. Our Tourists' Corner ... 61 9. States the Area Budget, January to March, 1948 ... 63 10. Doings in Other Provinces ... 67 1 Orissa Review * Index-1948-2013 11. All India Affairs ... 68 12. Relief & Rehabilitation ... 69 13. Coming Events of Interests ... 70 14. Medical Notes ... 70 15. Gandhi Memorial Fund ... 72 16. Development Schemes in Orissa ... 73 17. Our Distinguished Visitors ... 75 18. Development Notes ... 77 19. Policies and Decisions ... 80 20. Food Notes ... 81 21. Our Tourists Corner ... 83 22. Notice and Announcement ... 91 23. In State Areas ... 91 24. Doings of Other Provinces ... 92 25. Separation of the Judiciary from the Executive .. -

List of Engineering Colleges Under Bput Odisha

LIST OF ENGINEERING COLLEGES UNDER BPUT ODISHA SN NAME OF THE COLLEGE Category Address-I Address-II Address-III Dist PIN Name of the Trust Chairman Principal/Director Contact No. e-mail ID 1 ADARSHA COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING, Private Saradhapur Kumurisingha Angul 759122 Adarsha Educational Trust Mr. Mahesh Chandra Dhal Dr. Akshaya Kumar Singh 7751809969 [email protected] ANGUL 2 AJAY BINAY INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY, Private Plot No.-11/1/A Sector-1 CDA Cuttack 753014 Ajay Binay Institute of Technology- Dr. K. B. Mohapatra Dr. Leena Samantaray 9861181558 [email protected] CUTTACK Piloo Mody College of Achitecture 3 APEX INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & Private On NH-5 Pahala Bhubaneswar Khurda 752101 S.J.Charitable Trust Smt. Janaki Mudali Dr. Ashok Kumar Das 9437011165 MANAGEMENT, PAHALA 4 ARYAN INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING & Private Barakuda Panchagaon Bhubaneswar Khurda 752050 Aryan Educational Trust Dr. Madhumita Parida Prof.9Dr.) Sudhansu Sekhar 9437499464 [email protected] TECHNOLOGY, BHUBANESWAR Khuntia 5 BALASORE COLLEGE OF ENGINEERING & Private Sergarh Balasore 756060 Fakirmohan Educational & Charitable Mr. Manmath Kumar Biswal Prof. (Dr) Abhay Kumar 9437103129 [email protected] TECHNOLOGY, BALASSORE Trust Panda 6 BHADRAK INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING Private Barapada Bhadrak 756113 Barapada School of Engineering & Sri Laxmi Narayan Mishra Prof.(Dr.) Mohan Charan 9556041223 [email protected] AND TECHNOLOGY, BHADRAK Technology Society Panda 7 BHUBANESWAR COLLEGE OF Private Khajuria Jankia Khurda Oneness Eductationa & Charitable -

Gandhiji's Visit to Indupur - Dhumat

Orissa Review * August - 2004 Gandhiji's Visit to Indupur - Dhumat Sukadev Sahu Translated by Marina Priyadarshinee Mohapatra In 1933, the British Administration in India Veda, from Veda to Laksmanpur, Laksmanpur tried for a complete division of the Hindu to Gopinathpur, Bahukuda - Siswa - Patapur - society by according special voting rights to Nischinta Koili-Kalatia-Salar-Bhagawatipur- the untouchables. Gandhiji started hunger strike Kendrapada-Barimula-Indupur. Amidst many in Yaraveda jail opposing this people Jadumani Mangaraj, dangerous move of the British Gopabandhu Chaudhury, Administration and their anti- Narayan Birbar Samanta, Indian attitude. He came out Rajkrishna Bose, Rama Devi, successful in this attempt. Then Binod Kanungo, Annapurna started the movement against Maharana and others untouchability all over India. accompanied him. The people This was the first of its kind in of Dhumat-Indupur including India as prior to that there was the untouchables covered a no such movement against distance of three miles to untouchability. welcome Gandhiji. Being Orissa was fortunate overwhelmed by hearing the enough to become the centre- Bhajans sung by the stage of this movement. In untouchables Gandhiji told that 1934 Gandhiji started his long all his fatigue went away journey on foot from Puri, the listening to such melodious abode of Lord Jagannath. During his journey songs, the recital of Harinam-Kirtan by his on foot Gandhiji went to Patna for a few days Harijan bretherns. That was 31st of May, 1934. after covering some places in Cuttack District. A wonderful commotion was in the air of the Again he resumed his journey from Bairi after entire village. -

Review of Research

Review Of ReseaRch impact factOR : 5.7631(Uif) UGc appROved JOURnal nO. 48514 issn: 2249-894X vOlUme - 8 | issUe - 7 | apRil - 2019 __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ PICTURE OF ODISHA AS PROJECTED IN THE AKBAR NAMAH OF ABUL FAZL: A REAPPRAISAL Dr. Bhagabana Sahu Former Professor & Head , Department of History , Berhampur University, Berhampur, Ganjam (Odisha). ABSTRACT: Abul Fazl, the court historian of Akbar (author of Akbar-namah) was one of the greatest historians of medieval India. He was not only an exalted and trusted courtier, but also a friend, adviser, minister, diplomat and military commander of Akbar. It is divided into 3 parts. The first volume of this gigantic work contains the history of the reign of Babar to Humayun. Second volume is devoted to the detailed history of nearly 46 years of the reign of Akbar. The third and the concluding volume known as Ain-i-Akbari is an administrative report. It provides a complete picture of different provinces of the Mughal empire during the time of Akbar. An attempt has been made in this paper to present the picture of Orissa as gleaned in the Akbar-namah. KEYWORDS: Abul Fazl , greatest historians , Mughal empire. INTRODUCTION: Abul Fazl was one of the greatest historians of medieval India. He was born at Agra on 14th January, 1551 AD.1 He was not only an exalted and trusted courtier, but also a friend, adviser, minister, diplomat and military commander of Akbar. Abul Fazl began the work of Akbar-namah in 1595 completed and submitted it to Akbar in 1602. Akbar-namah is by far the greatest work in the whole series of Mahammadan histories of India.2 It is divided into 3 parts. -

Sl. No Name of the Employee with Designation Date of Joining in Present College Detail History of Posting Date of Retirement

Status of Employee-in-Position (Teaching) in Government Colleges College Name: Bhadrak Autonomous College, Bhadrak Sl. Name of the Employee with Designation Date of joining in Detail History of Posting Date of Remarks No Present college Retirement 1 Sri Parshuram Jena , Lecturer in English 21.10.11 Govt. Even. College, Rourkela 31.05.28 Rourkela Jr. College. Rourkela Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak 2 Sri Manmath Ku. Majhi, Lect. in Eng. 24.10.11 V. Deb College, Jaypur 30.04.30 V. Deb Jr. College, Jaypur Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak 3 Ms. Lopamudra Pattnaik ,Jr. Lect. in Eng. 2.11.11 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak 31.07.30 4 Smt. Mousumi Mahakul, Jr. Lect. in Eng. 26.6.14 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak N.A. Adhoc 5 Sri Bablu Sardar, Jr. Lect. In Odia 1.11.11 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak 30.6.33 6 Smt. Jyotsna Rani Kar, Jr. Lect. in Odia 5.8.14 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak N.A. Adhoc 7 Smt. Subhashree Nayak , Jr. Lect. In Odia 12.8.14 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak N.A. Adhoc 8 Sri Dharmendra Das,Jr. Lect. In Sans. 24.12.13 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak 31.5.44 9 sri Nrusingha Behera , Jr. Lect. In Hn. 26.6.14 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak N.A. Adhoc 10 Dr. Salman Raghib , Lect. In Urdu 17.2.2001 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak 31.10.25 11 Sri Ajay kumar Sethi , Lect. In Eco. 28.2.13 V. Deb. Jr. College, Jaypur 31.05.32 Bhadrak Junior College, Bhadrak 12 Sri khirod Kumar Choudhury , Jr.