Jihad Instead of Democracy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PHOTOJOURNALISM EDITORIAL Can There Be Too Much Coverage of a Conflict? the Question May Seem Disrespectful, but It Still Needs to Be Asked, and Answered

ASSOCIATION VISA POUR L’IMAGE - PERPIGNAN © LAURENT VAN DER STOCKT Couvent des Minimes, 24, rue Rabelais, 66000 Perpignan FOR LE MONDE/ Getty ImaGeS ReportaGe SEPTEMBER 2 Tel: +33 (0)4 68 62 38 00 Mosul, Iraq, March 19, 2017 e-mail: [email protected] - www.visapourlimage.com FB Visa pour l’Image - Perpignan TO 17, 2017 @Visapourlimage PRESIDENT JEAN-PAUL GRIOLET VICE-PRESIDENT / TREASURER PIERRE BRANLE COORDINATION ARNAUD FÉLICI ASSISTANTS (COORDINATION) ANAÏS MONTELS & JÉRÉMY TABARDIN PRESS / PUBLIC RELATIONS 2E BUREAU 18, rue Portefoin - 75003 Paris Tel: +33 (0)1 42 33 93 18 e-mail: [email protected] www.2e-bureau.com DIRECTOR SYLVIE GRUMBACH MANAGEMENT / ACCREDITATIONS VALÉRIE BOURGOIS PRESS MARTIAL HOBENICHE, CLÉMENCE ANEZOT TATIANA FOKINA, CAMILLE GRENARD, DANIELA JACQUET FESTIVAL MANAGEMENT IMAGES EVIDENCE 4, rue Chapon - Bâtiment B 75003 Paris Tel : +33 (0)1 44 78 66 80 e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] FB Jean Francois Leroy Twitter @jf_leroy Instagram @visapourlimage DIRECTOR GENERAL JEAN-FRANÇOIS LEROY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DELPHINE LELU COORDINATION CHRISTINE TERNEAU ASSISTANT LOUIS MARTINEZ SENIOR ADVISOR JEAN LELIÈVRE SENIOR ADVISOR – USA ELIANE LAFFONT SUPERINTENDANCE ALAIN TOURNAILLE TEXTS FOR EVENING SHOWS, EVENING PRESENTATIONS & RECORDED VOICE SONIA CHIRONI EVENING PRESENTATIONS PAULINE CAZAUBON “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR CAROLINE LAURENT-SIMON PROOFREADING OF FRENCH TEXTS & CAPTIONS BÉATRICE LEROY BLOG & “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR VINCENT JOLLY COMMUNITY MANAGER KYLA WOODS -

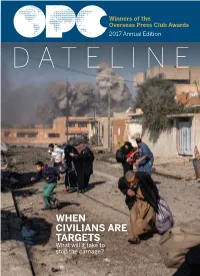

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

STRATEGIC TRENDS 2010 Is the First Issue of the Strategic Trends Series

Center for Security Studies STRATEGIC CSS ETH Zurich TRENDS 2010 STRATEGIC TRENDS offers a concise annual analysis of major developments in world affairs, with a primary focus on international security. Providing succinct Key Developments in Global Affairs interpretations of key trends rather than a comprehensive survey of events, this publication will appeal to analysts, policy-makers, academics, the media, and the interested public alike. It is produced by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. Strategic Trends is available both as an e-publication (www. sta.ethz.ch) and as a paperback book. STRATEGIC TRENDS 2010 is the first issue of the Strategic Trends series. Published in February 2010, it contains a global overview as well as chapters on the financial crisis, US foreign policy, non-proliferation and disarmament, resource nationalism, and crisis management. These have been identified by the Center for Security Studies as the main strategic trends in 2010. The Center for Security Studies (www.css.ethz.ch) at ETH Zurich specialises in research, teaching, and the provision of electronic services in international and Swiss security policy. An academic institute with a major think-tank capacity, it has a wide network of partners. The CSS is part of the Center for Comparative and International Studies (CIS), which includes the political science chairs of ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich. 2010 CSS ETH Zurich STRATEGIC TRENDS ST-2010-Cover.indd 1 25.01.2010 13:28:07 STRATEGIC TRENDS 2010 is also available electronically on the Strategic Trends Analysis website at: www.sta.ethz.ch Editor STRATEGIC TRENDS 2010: Daniel Möckli Series Editors STRATEGIC TRENDS: Andreas Wenger and Victor Mauer Contact: Center for Security Studies ETH Zurich Seilergraben 45–49 CH-8092 Zurich Switzerland This publication covers events up to 18 January 2010. -

Democracy and Tunisia

Democracy and Tunisia 27 August 2021 Image 1: Fethih Belaid/AFP via Getty Images. A protester lifts a Tunisian national flag during an anti-government rally in front of the parliament in Tunis, Tunisia, on 25 July 2021 Introduction President Kais Saied decided to enact Article 80 of the constitution on 25 July. Some Tunisians hailed it as a necessary intervention into a broken and stagnant political system. Others called it a coup, signifying the possible end of Tunisian democracy. Saied invoked emergency powers and suspended parliament for 30 days, a deadline which has since passed. He dismissed the prime minister, Hichem Mechichi, the defence and justice ministers. Saied called in the military, who surrounded the parliament. COVID-19 restrictions were extended, a nighttime curfew continued, and Saied reinforced a long-existing rule whereby gatherings of more than three people are not permitted. The president's move followed months of deadlock and disputes pitting him against prime minister Hichem Mechichi and a fragmented parliament as Tunisia sank into an economic crisis worsened by one of Africa's worst 1 Democracy and Tunisia COVID-19 outbreaks. This situation resulted in Saied claiming control over the executive, legislative and judicial branches of the government. Parts of the population drew together in large crowds and took to the streets once more to support Saeid's decision. This reaction reflects some Tunisian's anger towards the moderate Islamist Ennahda, the biggest party in parliament, and the government over political paralysis, economic stagnation, and the pandemic response. Initially, parliament speaker Rached Ghannouchi, the historical head of Ennahda, condemned Saied’s actions as an assault on democracy and urged Tunisians to take to the streets in opposition; he and the party swiftly changed their stance and called for communication rather than confrontation. -

Internal Displacementmonitoringcentre

Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2009 and Developments Trends of Global Overview Internal Displacement Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre Norwegian Refugee Council Internal Displacement Chemin de Balexert 7-9 CH-1219 Châtelaine (Geneva) Tel.: +41 22 799 07 00, Fax: +41 22 799 07 01 Global Overview of Trends and www.internal-displacement.org Developments in 2009 Internally displaced people worldwide December 2009 Turkey 954,000–1,201,000 Russian Federation Armenia Azerbaijan Uzbekistan 80,000 8,400 586,000 FYR Macedonia 3,400 Serbia 650 Turkmenistan 225,000– Undetermined 230,000 Georgia Kosovo At least Afghanistan 19,700 230,000 At least 297,000 Croatia 2,400 Bosnia & Herz. 114,000 Cyprus Up to 201,000 Pakistan 1,230,000 Israel Undetermined Nepal 50,000–70,000 Occupied Palestinian Territory At least 160,000 India Algeria At least 500,000 Undetermined Chad 168,000 Bangladesh Senegal Iraq 60,000–500,000 24,000–40,000 2,764,000 Mexico The Philippines 5,000–8,000 Liberia Sri Lanka 125,000–188,000 Undetermined Syria 433,000 400,000 Côte d´Ivoire Lebanon Undetermined 90,000–390,000 Guatemala Togo Yemen Myanmar Undetermined Undetermined At least 175,000 At least 470,000 Indonesia Eritrea 70,000–120,000 Timor-Leste Niger 10,000 Colombia 6,500 400 3,300,000–4,900,000 Ethiopia Nigeria 300,000– Undetermined CAR 350,000 162,000 Peru Sudan Somalia 150,000 4,900,000 1,500,000 Congo Kenya 7,800 Undetermined DRC Uganda 1,900,000 At least 437,000 Angola Rwanda Undetermined Burundi Undetermined 100,000 Zimbabwe 570,000–1,000,000 Internal Displacement Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2009 May 2010 Internally displaced children shell their family’s monthly ten-kilogramme ration of beans inside their home at Buhimbe Camp near Goma in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. -

Internal Displacement: Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2009

Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2009 and Developments Trends of Global Overview Internal Displacement Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre Norwegian Refugee Council Internal Displacement Chemin de Balexert 7-9 CH-1219 Châtelaine (Geneva) Tel.: +41 22 799 07 00, Fax: +41 22 799 07 01 Global Overview of Trends and www.internal-displacement.org Developments in 2009 Internally displaced people worldwide December 2009 Turkey 954,000–1,201,000 Russian Federation Armenia Azerbaijan Uzbekistan 80,000 8,400 586,000 FYR Macedonia 3,400 Serbia 650 Turkmenistan 225,000– Undetermined 230,000 Georgia Kosovo At least Afghanistan 19,700 230,000 At least 297,000 Croatia 2,400 Bosnia & Herz. 114,000 Cyprus Up to 201,000 Pakistan 1,230,000 Israel Undetermined Nepal 50,000–70,000 Occupied Palestinian Territory At least 160,000 India Algeria At least 500,000 Undetermined Chad 168,000 Bangladesh Senegal Iraq 60,000–500,000 24,000–40,000 2,764,000 Mexico The Philippines 5,000–8,000 Liberia Sri Lanka 125,000–188,000 Undetermined Syria 433,000 400,000 Côte d´Ivoire Lebanon Undetermined 90,000–390,000 Guatemala Togo Yemen Myanmar Undetermined Undetermined At least 175,000 At least 470,000 Indonesia Eritrea 70,000–120,000 Timor-Leste Niger 10,000 Colombia 6,500 400 3,300,000–4,900,000 Ethiopia Nigeria 300,000– Undetermined CAR 350,000 162,000 Peru Sudan Somalia 150,000 4,900,000 1,500,000 Congo Kenya 7,800 Undetermined DRC Uganda 1,900,000 At least 437,000 Angola Rwanda Undetermined Burundi Undetermined 100,000 Zimbabwe 570,000–1,000,000 Internal Displacement Global Overview of Trends and Developments in 2009 May 2010 Internally displaced children shell their family’s monthly ten-kilogramme ration of beans inside their home at Buhimbe Camp near Goma in North Kivu, Democratic Republic of the Congo. -

The Middle-Class Killers of Tunisia

TUNISIA The Islamists who attacked the national museum were far from poor or marginalised The middle-class killers of Tunisia BY PATRICK MARKEY AND TAREK AMARA SPECIAL REPORT 1 TUNISIA MIDDLE CLASS KILLERS SBIBA, TUNISIA, MAY 17, 2015 ne of the young men was a high school literature student who Ohelped his father tend the family olive trees in their isolated farming com- munity near the Algerian border. The other lived in the capital Tunis, had a taste for fashion and worked as a travel agent. Jabeur Khachnaoui and Yassine el-Abidi came from stable, middle-class families and were well educated. On March 18, they came together to attack Tunisia’s Bardo Museum, shoot- ing foreign tourists as they filed off buses outside the museum, and then taking more tourists hostage inside. SHATTERED: A tourist bus after the attack on the national museum in Tunis. The March attack was Over three hours they killed 22 people one of the worst in a country that has largely escaped the region’s turmoil. Cover: One of the attackers, in all, including French, Italian, Japanese, Yassine al-Abidi, in a family photograph held by his cousin. REUTERS/ZOUBEIR SOUISSI (2) Russian and Spanish visitors. Security forc- es eventually stormed the building and shot and killed the hostage-takers. Was it extremist recruiters? men go abroad for training or to fight, and To their families, the two young men Was it the mosque? All I know is I return like ticking bombs. “The ones that seemed to lead normal lives. But accord- brought him up right. -

ZOHRA BENSEMRA REUTERS ZOHRA LIEU BENSEMRA ÉGLISE DES DOMINICAINS REUTERS DES VIES English Version Below SUR LE FIL

ZOHRA BENSEMRA REUTERS ZOHRA LIEU BENSEMRA ÉGLISE DES DOMINICAINS REUTERS DES VIES English version below SUR LE FIL La première photo importante que Zohra arabe et la violence confessionnelle, puis a tourmentée de se sentir impuissante, Zohra Bensemra a prise montrait les ravages causés passé trois ans en tant que photographe en chef Bensemra s’est mise à la recherche de cette par un attentat à la voiture piégée dans la au Pakistan. femme dans un camp de réfugiés, montrant sa capitale algérienne. Elle avait 24 ans. « C’était De langues maternelles française et algérienne, photo jusqu’à ce qu’on la conduise à elle. Elles la première fois que je voyais des corps gisant elle a appris en chemin l’anglais et l’arabe pour ont bu le thé en évoquant le sort des poulets sur le sol. J’ai passé la journée à pleurer, j’étais pouvoir parler avec ceux qu’elle photographie. que cette femme avait élevés pendant la guerre, encore en larmes quand je me suis couchée. Elle s’intéresse à la vie des gens ordinaires : dans sa cave, au plus fort des bombardements. Au réveil, j’étais une nouvelle personne… Je me des enfants réfugiés qui jouent dans suis rendu compte que c’était ça la photographie un bidonville, des femmes d’affaires « …Mais nous ne Zohra Bensemra dit que son pour moi : montrer la souffrance engendrée par à Islamabad, d’autres arborant leurs faisons que notre travail consiste non pas à la guerre. » tatouages traditionnels en Algérie, expliquer mais à témoigner. Le militantisme islamiste a ensuite gagné du des familles de migrants qui fuient travail, témoigner, « C’est difficile de braquer terrain et son pays a plongé dans une guerre vers l’Europe. -

UNICEF-Photo of the Year 2017

UNICEF-Photo of the Year 2017 First Prize 2017 Syria: The face of a tormented childhood Zahra’s face. The face of a five-year-old Syrian girl in a refugee camp in Jordan. In 2015, Zahra’s parents fled the war in Syria with her and seven other children. They have lived in a tent ever since. Her father, who used to work as a taxi driver and farmer, is looking for work on the fields of the Jordan Valley; his children have no chance of attending school. Zahra was far from the first refugee child photographer Muhammed Muheisen, born in 1981 in Jerusalem, had met. The humanitarian tragedies in the Middle East, Pakistan and Afghanistan are something the renowned photographer, who had worked many years for AP, knows all too well. But for him, Zahra’s face and her eyes, in particular, were symbolic for the fate of hundreds of thousands of girls and boys: the quiet sadness of the most innocent victims of war, displacement and exile. Having experienced an unspeakable amount of violence, these children initially have nothing else to cope with it than helplessness and disbelief. The face of a childhood lost forever. Photographer: Muhammed Muheisen, Jordan (AP/dpa) Second Prize 2017 Bangladesh: The exodus of the Rohingya Although they had lived for generations in Myanmar’s Rakhine state, the military junta’s 1982 Citizenship Act rendered them stateless. As a result, the Muslim Rohingya were excluded from mostly Buddhist Myanmar’s official list of 135 ethnic groups; so most of their children have no access to medical help and are not allowed to attend school. -

THE CASBAH of ALGIERS: Cultural Heritage As a Political Tool

THE CASBAH OF ALGIERS: Cultural Heritage as a Political Tool Gwendolyn Peck BS Architecture, University of Michigan, 2013 Committee: Sheila Crane (Advisor) Shiqiao Li Andrew Johnston 5/1/2016 A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Department of Architectural History in the School of Architecture at the University of Virginia in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree Master of Architectural History 1 Table of Contents Introduction 4 I. Colonialism and the “Traditional City” 10 II. Nation Building with Cultural Heritage 18 III. World Heritage as an International Image 46 Conclusion 61 Bibliography 66 Illustrations 72 2 List of Illustrations Fig. 1 Sandervalya, Boulevard front de mer, April 18 2008, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Algercentre_front_de_mer.JPG Fig. 2 JeanMarie Pirard, Etage en surplomb de la rue en haute Casbah, Oct. 20 2007, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ruelle_dans_la_haute_casbah_Alger.JPG. Fig. 3 Gerard van Keulen, Algiers c. 1690, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_Algiers#/media/File:La_cite_le_port_et_le_mole_d_Alger.jpg Fig. 4 Neurdein frères, Panorama d’Alger. Vue prise de la Casbah, Getty Research Institute, http://hdl.handle.net/10020/2008r3_4020. Fig. 5 Sakina Missoum, Alger à L’époque Ottomane: La Médina et La Maison Traditionnelle (AixenProvence: Edisud, 2003). Left: Dar avec Chbak II.2 Raiah Rabah, 2; Right: Dar I.14 Impasse Sidi Driss Hamidouche, 2. Fig. 6 Sakina Missoum, Alger à L’époque Ottomane: La Médina et La Maison Traditionnelle (AixenProvence: Edisud, 2003). Left: Dwira II.5 Raiah Rabah, 6; Right: Dar II.3 Raiah Rabah, 4. Fig. 7 Yves Jalabert, Intérieur de Dar Hassan Pacha. -

International Reports 3/2016

KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG 3|2016 INTERNATIONAL REPORTS Rise and Fall of Regional Powers INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 3 | 2016 Editorial Dear Readers, A constant struggle for power and influence between states has always figured among the main characteristics of international politics. Regional powers can be considered the middle manage- ment of world politics: sufficiently powerful to make their mark on the region and take on a political and economic leadership role, but not yet or no longer powerful enough to be able to fill this role at the global level as well. In this connection, particular attention is due to those countries that have succeeded in developing into significant powers with regional influence or even further. This applies first and foremost to China, which has become considerably more influential in political, economic and military terms within just a few decades. One of the vehicles China uses to pursue its global political aims is the BRICS association which several authors deal with to start this issue off. While the article gathers different perspectives on BRICS, it illustrates above all one main point: the recent economic problems in most of the member states have strengthened China’s dominance within the group even further. The economic development in Vietnam, the second emerging econ- omy in Asia investigated in this issue, over the last three decades has meant that this country also plays an increasingly important role in the region. Apart from Vietnam’s economic strength, this has above all to do with the importance of its location on the South China Sea in terms of regional and geopolitics, although this not only entails opportunities, but also some risks, as Peter Girke reports. -

The Veiled Muslim Woman As Subject in Contemporary Art: the Role of Location, Autobiography, and the Documentary Image

[IR 16.4 (2013) 417–442] Implicit Religion (print) ISSN 1463-9955 doi:10.1558/imre.v16i4.417 Implicit Religion (online) ISSN 1743-1697 The Veiled Muslim Woman as Subject in Contemporary Art: The Role of Location, Autobiography, and the Documentary Image Valerie Behiery Independent scholar [email protected] Abstract That the veil sign often operates to deny both veiled and unveiled Muslim women their status as subjects implies that references to veiled subjectivity propose an al- ternative vision. This article examines representations of the veil in contemporary art that displace Western mainstream perceptions by effectively portraying veiled Muslim women as subjects, therefore laying claim to the transformative capacity of selfhood and image. These representations are intimately linked to the phenom- enon of globalization in that their recent visibility is due both to artists looking and working through another gaze/cultural screen and to a shift in the Western art apparatus that now exhibits their work. While they relate to other types of images of the veil in contemporary art in that they implicitly contextualize the veil and challenge the stereotypes surrounding it, they differ in that they are neither nostal- gic nor contestatory. Rather, the art works discussed, relating to location, autobiog- raphy and the desire to document, are rooted in daily life and memory. Their picto- rial language is not alien to Western visual culture, making their novel depictions of veiled women, and thus by extension their and the veil’s diversity, more salient. Keywords the veil in contemporary art, representation of Muslims, self-representa- tion of Muslims, Muslim women, postcolonial art, art and difference It thus remains a matter of political and cultural urgency to reconceptual- ize the economy of multiple gazes that filter through, slide off and remake the veil.