International Reports 4/2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MYSTIC LEADER ©Christian Bobst Village of Keur Ndiaye Lo

SENEGAL MYSTIC LEADER ©Christian Bobst Village of Keur Ndiaye Lo. Disciples of the Baye Fall Dahira of Cheikh Seye Baye perform a religious ceremony, drumming, dancing and singing prayers. While in other countries fundamentalists may prohibit music, it is an integral part of the religious practice in Sufism. Sufism is a form of Islam practiced by the majority of the population of Senegal, where 95% of the country’s inhabitants are Muslim Based on the teachings of religious leader Amadou Bamba, who lived from the mid 19th century to the early 20th, Sufism preaches pacifism and the goal of attaining unity with God According to analysts of international politics, Sufism’s pacifist tradition is a factor that has helped Senegal avoid becoming a theatre of Islamist terror attacks Sufism also teaches tolerance. The role of women is valued, so much so that within a confraternity it is possible for a woman to become a spiritual leader, with the title of Muqaddam Sufism is not without its critics, who in the past have accused the Marabouts of taking advantage of their followers and of mafia-like practices, in addition to being responsible for the backwardness of the Senegalese economy In the courtyard of Cheikh Abdou Karim Mbacké’s palace, many expensive cars are parked. They are said to be gifts of his followers, among whom there are many rich Senegalese businessmen who live abroad. The Marabouts rank among the most influential men in Senegal: their followers see the wealth of thei religious leaders as a proof of their power and of their proximity to God. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

African Studies Association 59Th Annual Meeting

AFRICAN STUDIES ASSOCIATION 59TH ANNUAL MEETING IMAGINING AFRICA AT THE CENTER: BRIDGING SCHOLARSHIP, POLICY, AND REPRESENTATION IN AFRICAN STUDIES December 1 - 3, 2016 Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington, D.C. PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Benjamin N. Lawrance, Rochester Institute of Technology William G. Moseley, Macalester College LOCAL ARRANGEMENTS COMMITTEE CHAIRS: Eve Ferguson, Library of Congress Alem Hailu, Howard University Carl LeVan, American University 1 ASA OFFICERS President: Dorothy Hodgson, Rutgers University Vice President: Anne Pitcher, University of Michigan Past President: Toyin Falola, University of Texas-Austin Treasurer: Kathleen Sheldon, University of California, Los Angeles BOARD OF DIRECTORS Aderonke Adesola Adesanya, James Madison University Ousseina Alidou, Rutgers University Souleymane Bachir Diagne, Columbia University Brenda Chalfin, University of Florida Mary Jane Deeb, Library of Congress Peter Lewis, Johns Hopkins University Peter Little, Emory University Timothy Longman, Boston University Jennifer Yanco, Boston University ASA SECRETARIAT Suzanne Baazet, Executive Director Kathryn Salucka, Program Manager Renée DeLancey, Program Manager Mark Fiala, Financial Manager Sonja Madison, Executive Assistant EDITORS OF ASA PUBLICATIONS African Studies Review: Elliot Fratkin, Smith College Sean Redding, Amherst College John Lemly, Mount Holyoke College Richard Waller, Bucknell University Kenneth Harrow, Michigan State University Cajetan Iheka, University of Alabama History in Africa: Jan Jansen, Institute of Cultural -

Shari'ah and the Secular State

Shari’ah and the Secular State: Popular Support for and Opposition to Islamic Family Law in Senegal by Carrie S. Konold A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Political Science) in The University of Michigan 2010 Doctoral Committee: Professor Mark A. Tessler, Co-Chair Associate Professor Ted Brader, Co-Chair Professor Mamadou Diouf, Columbia University Professor Jennifer A. Widner, Princeton University © Copyright Carrie S. Konold 2010 Dedication To my parents, Phyllis and David Konold, With love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements I gratefully acknowledge the many individuals and institutions that have made this research possible. First, I thank my undergraduate teachers at Wellesley College— especially Craig Murphy, Joel Krieger, and Ann Velenchik—who inspired my love of learning and the courage to pursue my passions. I am indebted to my advisors at the University of Michigan who have provided intellectual mentorship and friendship throughout my graduate training, research, and writing. Thank you to Ted Brader, Mamadou Diouf, Mark Tessler, and Jennifer Widner for sharing your expertise and encouragement. It has been a true pleasure to know and work with you. Thank you to the many institutions that have funded various portions of my graduate training, conference travel, field research, and dissertation research and writing. At the University of Michigan, I thank the Center for the Education of Women, the International Institute, the Department of Political Science, the Rackham Graduate School, and the Center for Afroamerican and African Studies. I also thank the National Science Foundation, Fulbright IIE, CAORC, Wellesley College, the Charlotte W. -

PHOTOJOURNALISM EDITORIAL Can There Be Too Much Coverage of a Conflict? the Question May Seem Disrespectful, but It Still Needs to Be Asked, and Answered

ASSOCIATION VISA POUR L’IMAGE - PERPIGNAN © LAURENT VAN DER STOCKT Couvent des Minimes, 24, rue Rabelais, 66000 Perpignan FOR LE MONDE/ Getty ImaGeS ReportaGe SEPTEMBER 2 Tel: +33 (0)4 68 62 38 00 Mosul, Iraq, March 19, 2017 e-mail: [email protected] - www.visapourlimage.com FB Visa pour l’Image - Perpignan TO 17, 2017 @Visapourlimage PRESIDENT JEAN-PAUL GRIOLET VICE-PRESIDENT / TREASURER PIERRE BRANLE COORDINATION ARNAUD FÉLICI ASSISTANTS (COORDINATION) ANAÏS MONTELS & JÉRÉMY TABARDIN PRESS / PUBLIC RELATIONS 2E BUREAU 18, rue Portefoin - 75003 Paris Tel: +33 (0)1 42 33 93 18 e-mail: [email protected] www.2e-bureau.com DIRECTOR SYLVIE GRUMBACH MANAGEMENT / ACCREDITATIONS VALÉRIE BOURGOIS PRESS MARTIAL HOBENICHE, CLÉMENCE ANEZOT TATIANA FOKINA, CAMILLE GRENARD, DANIELA JACQUET FESTIVAL MANAGEMENT IMAGES EVIDENCE 4, rue Chapon - Bâtiment B 75003 Paris Tel : +33 (0)1 44 78 66 80 e-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] FB Jean Francois Leroy Twitter @jf_leroy Instagram @visapourlimage DIRECTOR GENERAL JEAN-FRANÇOIS LEROY EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR DELPHINE LELU COORDINATION CHRISTINE TERNEAU ASSISTANT LOUIS MARTINEZ SENIOR ADVISOR JEAN LELIÈVRE SENIOR ADVISOR – USA ELIANE LAFFONT SUPERINTENDANCE ALAIN TOURNAILLE TEXTS FOR EVENING SHOWS, EVENING PRESENTATIONS & RECORDED VOICE SONIA CHIRONI EVENING PRESENTATIONS PAULINE CAZAUBON “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR CAROLINE LAURENT-SIMON PROOFREADING OF FRENCH TEXTS & CAPTIONS BÉATRICE LEROY BLOG & “MEET THE PHOTOGRAPHERS” MODERATOR VINCENT JOLLY COMMUNITY MANAGER KYLA WOODS -

Introduction to Theology

INTRODUCTION TO THEOLOGY Θεός –God Λόγς -Science, Word, Discourse, Talk, Study Hence , Θεολόγια theologia = theolog y,means simply God talk, study of God, science of understanding God. Augustine : Theology is “rational discussion respecting the deity” Theology is an attempt of understanding God as He is revealed. In Patristic Greek sources, theologia could refer the inspired knowledge of, and teaching about, the essential nature of God. In Scholastic Latin sources, the term denotes rational study of the doctrines of the Christian religion. Thomas Aquinas , theology is constituted by a triple aspect: what is taught by God, what teaches of God and what leads to God ( Latin : Theologia a Deo docetur, Deum docet, et ad Deum ducit ). Christian theology is simply an attempt to understand God as He is revealed in the Bible.Theology is the art and science of knowing what we can know and understand about God in an organized and understandable manner. Theology in its profound meaning not consisted of any kind of human analysis or intellectual exercises about Divinity, rather it is an understanding of what God has done through His Eternal Logos to the humanity and howthe Incarnated Logos entered into our profane history and made it a salvation history . Therefore, the soul of theology is God who has revealed and offered himself to the mankind. In short, theology is a divinely inspired human attemptto understand God who has revealed himself in space and time. It is the systematic, orderly and rational reproduction of what one has already experienced and accepted through faith. Theology, therefore is a science which should be studied on kneels. -

Carol Shenk Bornman Is Working in Louga with Friends of the Wolof and Mennonite Mission Network Since 1999

A MEETING OF WORLDS IN SENEGAL Carol Shenk Bornman I relax on a mat in our main room with my two friends, Aminata and Fatou, resting during the heat of the afternoon. It is July 26, 2005, and sweet black tea called attaaya is boiling atop the charcoal burner. In the office nearby, the space shuttle Discovery commentary from www.news.yahoo.com plays on the computer where Caleb & Laurel watch the astronauts working in the shuttle. Upstairs, Isaiah watches the second Lord of the Rings movie. Then we hear the Muslim call to prayer from the mosque close by, much louder than the other two sounds, and quite jarring. A meeting of worlds: space shuttle and local mosque, LOTR characters and astronauts, a powerful prayer call and a powerful ring. We have many opportunities to ponder the meeting of worlds as we work in Senegal. Sometimes we sense a freedom to “push against” boundaries that seem to be set in stone. But more of the time we spend listening to our friends, getting a sense of where they are at in their world view and in their lives, and reading Scripture with them. Senegal’s Four Main Groups of Muslims I would like to start with a brief description of the four main groups of Muslims that live in Senegal, four active Sufi organizations that can also be found in other parts of Africa and around the world. Most statistics cite that 94% of Senegalese belong to one of these organizations, but the majority of those belong to the Tijanis or the Mourides. -

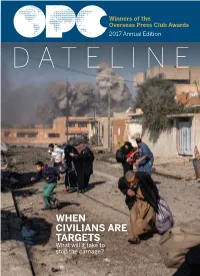

WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What Will It Take to Stop the Carnage?

Winners of the Overseas Press Club Awards 2017 Annual Edition DATELINE WHEN CIVILIANS ARE TARGETS What will it take to stop the carnage? DATELINE 2017 1 President’s Letter / dEIdRE dEPkE here is a theme to our gathering tonight at the 78th entries, narrowing them to our 22 winners. Our judging process was annual Overseas Press Club Gala, and it’s not an easy one. ably led by Scott Kraft of the Los Our work as journalists across the globe is under Angeles Times. Sarah Lubman headed our din- unprecedented and frightening attack. Since the conflict in ner committee, setting new records TSyria began in 2011, 107 journalists there have been killed, according the for participation. She was support- Committee to Protect Journalists. That’s more members of the press corps ed by Bill Holstein, past president of the OPC and current head of to die than were lost during 20 years of war in Vietnam. In the past year, the OPC Foundation’s board, and our colleagues also have been fatally targeted in Iraq, Yemen and Ukraine. assisted by her Brunswick colleague Beatriz Garcia. Since 2013, the Islamic State has captured or killed 11 journalists. Almost This outstanding issue of Date- 300 reporters, editors and photographers are being illegally detained by line was edited by Michael Serrill, a past president of the OPC. Vera governments around the world, with at least 81 journalists imprisoned Naughton is the designer (she also in Turkey alone. And at home, we have been labeled the “enemy of the recently updated the OPC logo). -

Local Ownership of Projects in Situations of Fragility and Instability

USAID FUNDS AND LOCALS OWN: LOCAL OWNERSHIP OF PROJECTS IN SITUATIONS OF FRAGILITY AND INSTABILITY. THE CASES OF IDEJEN IN HAITI AND BUILDING PEACE AND PROSPERITY IN CASAMANCE, SENEGAL by Joseph N. Sany A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Public Policy Committee: _______________________________________ Jack A. Goldstone, Chair _______________________________________ Janine Wedel _______________________________________ Allison Frendak-Blume _______________________________________ Terrence Lyons _______________________________________ Clare Ignatowski, External Reader _______________________________________ James P. Pfiffner, Program Director _______________________________________ Edward Rhodes, Dean Date: __________________________________ Spring Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA USAID Funds and Locals Own: Local Ownership of Projects in Situations of Fragility and Instability. The cases of IDEJEN in Haiti and Building Peace and Prosperity in Casamance , Senegal A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University By Joseph Nzima Sany Master of Science George Mason University, 2005 Director: Jack Goldstone, Professor School of Public Policy Spring Semester 2013 George Mason University Fairfax, VA Copyright 2013 Joseph Nzima Sany All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION To my wife, Melanie and our four children; I hope this work inspires them to continuously make a meaningful contribution for the betterment of humankind. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am very grateful to my wife, Melanie, who advised, supported and encouraged me to move forward with this research, when obstacles seemed insurmountable. Writing a dissertation is not only an intellectual endeavor, it is also a psychological one. It tests one’s resolve, stamina and determination. -

Stephen Burman

SENEGALESE ISLAM: OLD STRENGTHS, NEW CHALLENGES KEY POINTS Islam in Senegal is based around sufi brotherhoods. These have substantial connections across West Africa, including Mali, as well as in North Africa, including Morocco and Algeria. They are extremely popular and historically closely linked to the state. Salafism has had a small presence since the mid-twentieth century. Established Islam in Senegal has lately faced new challenges: o President Wade’s (2000-2012) proximity to the sufi brotherhoods strained the division between the state and religion and compromised sufi legitimacy. o A twin-track education system. The state has a limited grip on the informal education sector, which is susceptible to extremist teaching. o A resurgence of salafism, evidenced by the growing influence of salafist community organisations and reports of support from the Gulf. o Events in Mali and Senegal’s support to the French-led intervention have led to greater questioning about the place of Islam in regional identity. Senegal is therefore vulnerable to growing Islamist extremism. Its institutions and sufi brotherhoods put it in a strong position to resist it, but this should not be taken for granted. DETAIL Mali, 2012. Reports on the jihadist takeover of the North include references to around 20 speakers of Wolof, a language whose native speakers come almost exclusively from Senegal. Earlier reporting refers to a Senegalese contingent among the jihadist kidnappers of Canadian diplomat Robert Fowler. These and other reports (such as January 2013 when an imam found near the Senegal-Mali border was arrested for jihadist links) put into sharper focus the role of Islam in Senegal. -

STRATEGIC TRENDS 2010 Is the First Issue of the Strategic Trends Series

Center for Security Studies STRATEGIC CSS ETH Zurich TRENDS 2010 STRATEGIC TRENDS offers a concise annual analysis of major developments in world affairs, with a primary focus on international security. Providing succinct Key Developments in Global Affairs interpretations of key trends rather than a comprehensive survey of events, this publication will appeal to analysts, policy-makers, academics, the media, and the interested public alike. It is produced by the Center for Security Studies (CSS) at ETH Zurich. Strategic Trends is available both as an e-publication (www. sta.ethz.ch) and as a paperback book. STRATEGIC TRENDS 2010 is the first issue of the Strategic Trends series. Published in February 2010, it contains a global overview as well as chapters on the financial crisis, US foreign policy, non-proliferation and disarmament, resource nationalism, and crisis management. These have been identified by the Center for Security Studies as the main strategic trends in 2010. The Center for Security Studies (www.css.ethz.ch) at ETH Zurich specialises in research, teaching, and the provision of electronic services in international and Swiss security policy. An academic institute with a major think-tank capacity, it has a wide network of partners. The CSS is part of the Center for Comparative and International Studies (CIS), which includes the political science chairs of ETH Zurich and the University of Zurich. 2010 CSS ETH Zurich STRATEGIC TRENDS ST-2010-Cover.indd 1 25.01.2010 13:28:07 STRATEGIC TRENDS 2010 is also available electronically on the Strategic Trends Analysis website at: www.sta.ethz.ch Editor STRATEGIC TRENDS 2010: Daniel Möckli Series Editors STRATEGIC TRENDS: Andreas Wenger and Victor Mauer Contact: Center for Security Studies ETH Zurich Seilergraben 45–49 CH-8092 Zurich Switzerland This publication covers events up to 18 January 2010. -

Democracy and Tunisia

Democracy and Tunisia 27 August 2021 Image 1: Fethih Belaid/AFP via Getty Images. A protester lifts a Tunisian national flag during an anti-government rally in front of the parliament in Tunis, Tunisia, on 25 July 2021 Introduction President Kais Saied decided to enact Article 80 of the constitution on 25 July. Some Tunisians hailed it as a necessary intervention into a broken and stagnant political system. Others called it a coup, signifying the possible end of Tunisian democracy. Saied invoked emergency powers and suspended parliament for 30 days, a deadline which has since passed. He dismissed the prime minister, Hichem Mechichi, the defence and justice ministers. Saied called in the military, who surrounded the parliament. COVID-19 restrictions were extended, a nighttime curfew continued, and Saied reinforced a long-existing rule whereby gatherings of more than three people are not permitted. The president's move followed months of deadlock and disputes pitting him against prime minister Hichem Mechichi and a fragmented parliament as Tunisia sank into an economic crisis worsened by one of Africa's worst 1 Democracy and Tunisia COVID-19 outbreaks. This situation resulted in Saied claiming control over the executive, legislative and judicial branches of the government. Parts of the population drew together in large crowds and took to the streets once more to support Saeid's decision. This reaction reflects some Tunisian's anger towards the moderate Islamist Ennahda, the biggest party in parliament, and the government over political paralysis, economic stagnation, and the pandemic response. Initially, parliament speaker Rached Ghannouchi, the historical head of Ennahda, condemned Saied’s actions as an assault on democracy and urged Tunisians to take to the streets in opposition; he and the party swiftly changed their stance and called for communication rather than confrontation.