Scholarworks@UNO Adrift

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

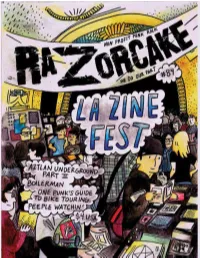

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #19 www.razorcake.com ight around the time we were wrapping up this issue, Todd hours on the subject and brought in visual aids: rare and and I went to West Hollywood to see the Swedish band impossible-to-find records that only I and four other people have RRRandy play. We stood around outside the club, waiting for or ancient punk zines that have moved with me through a dozen the show to start. While we were doing this, two young women apartments. Instead, I just mumbled, “It’s pretty important. I do a came up to us and asked if they could interview us for a project. punk magazine with him.” And I pointed my thumb at Todd. They looked to be about high-school age, and I guess it was for a About an hour and a half later, Randy took the stage. They class project, so we said, “Sure, we’ll do it.” launched into “Dirty Tricks,” ripped right through it, and started I don’t think they had any idea what Razorcake is, or that “Addicts of Communication” without a pause for breath. It was Todd and I are two of the founders of it. unreal. They were so tight, so perfectly in time with each other that They interviewed me first and asked me some basic their songs sounded as immaculate as the recordings. On top of questions: who’s your favorite band? How many shows do you go that, thought, they were going nuts. Jumping around, dancing like to a month? That kind of thing. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Issue 01 One..Two...Three? Student Tests Newton’S Laws, Fails Tuesday, March 20Th

catalyst issue 01 One..Two...Three? Student Tests Newton’s Laws, Fails Tuesday, March 20th. stairs. responded Stevens when ques- A local teenager, whose and like, they were totally saying Michael Keets, a student at “I had no idea that stairs tioned about Keets’ comment, name will be kept confidential due to was completely wrong." Clark com- Spotsylvania County’s prestigious could be considered an outside “These kids never listen, especially his minor status, recently discovered mented. "I didn't like that at all." Spotsylvania Middle School, was force. I mean, according to every- Michael Keets. You tell them not to exactly how many licks it takes to get The federal government severally injured while attempting to thing else I’ve learned, they can’t be try anything we talk about in class, to the center of a Tootsie Pop. The has sided with the makers of the prove Newton’s first law of physics. a force because they have no direc- and they think you’re asking them if discovered, however, was not free of delicious treat in this case, however, Brian Stevens, the teacher who tion. They aren’t a vector quantity,” they want some cake. And they all controversy and suspicions of fraud. barring the boy from releasing his allegedly introduced Keets to said commented a heavily drugged want cake.” For years, the makers of findings, and stating that he must law, commented that he in no way Keets from his hospital bed the day Stevens also attempted to the aforementioned lollipop have revoke his press release. -

Precious but Not Precious UP-RE-CYCLING

The sounds of ideas forming , Volume 3 Alan Dunn, 22 July 2020 presents precious but not precious UP-RE-CYCLING This is the recycle tip at Clatterbridge. In February 2020, we’re dropping off some stuff when Brigitte shouts “if you get to the plastic section sharpish, someone’s throwing out a pile of records.” I leg it round and within seconds, eyes and brain honed from years in dank backrooms and charity shops, I smell good stuff. I lean inside, grabbing a pile of vinyl and sticking it up my top. There’s compilations with Blondie, Boomtown Rats and Devo and a couple of odd 2001: A Space Odyssey and Close Encounters soundtracks. COVER (VERSIONS) www.alandunn67.co.uk/coverversions.html For those that read the last text, you’ll enjoy the irony in this introduction. This story is about vinyl but not as a precious and passive hands-off medium but about using it to generate and form ideas, abusing it to paginate a digital sketchbook and continuing to be astonished by its magic. We re-enter the story, the story of the sounds of ideas forming, after the COVER (VERSIONS) exhibition in collaboration with Aidan Winterburn that brings together the ideas from July 2018 – December 2019. Staged at Leeds Beckett University, it presents the greatest hits of the first 18 months and some extracts from that first text that Aidan responds to (https://tinyurl.com/y4tza6jq), with me in turn responding back, via some ‘OUR PRICE’ style stickers with quotes/stats. For the exhibition, the mock-up sleeves fabricated by Tom Rodgers look stunning, turning the digital detournements into believable double-sided artefacts. -

Dubious Voices

Dubious Voices Senior Creative Writing Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree Bachelor of Arts with A Major in Creative Writing at The University of North Carolina at Asheville Fall 2007 By Vicente J Hernandez Thesis Advisor Dr. Dubious Voices short stories by Vicente James Hernandez 1207 Beeston Court, Wilmington NC 28411 (910)262-6125 [email protected] Dubious Voices Hernandez 3 Contents The First Listen...................................4 Acid....................................................11 My Girlfriend's Pants .......................... 17 Secret ..................................................23 Look at the Wall ..................................27 Out......................................................31 No Thanks ...........................................43 Sign..................................................... 48 Mya's Roommate Moves Out.............. 54 Shadows ............................................. 59 I Am In Arcadia...................................76 Hernandez 4 'The First Listen" Perhaps like every other late twenty-something, white male, downtown apartment resident I was partially educated with artistic aspirations; had rich parents that inconspicuously named me Alex; and lived in debt with clothes on the floor and dishes that spent most of their time rusting in the sink. I spent most of my time planning out sculptures in my sketchbook. They were useless things that made me no money and took up space. As my brother, Jake, loved to conspicuously remind me. I lived in an apartment with him. He was younger, and I gained points for maturity but still delivered that desperate monologue hi hopes of gaining a drop of sympathy: "It was actually pretty bad. I mean I am glad I had the experience, just because it was an experience. But, based on that night, I have decided that I don't enjoy drinking plastic bottled tequila with salt on my tongue, discovering my knee is miraculously bleeding on its own, not being able to figure out or remember if I know the person driving the car. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Liars, Lovers, and Thieves: Being Adolescent Readers and Writers in Young Adult Literature and Life Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2gm2b967 Author Crawford, Suzanne Mills Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Liars, Lovers, and Thieves: Being Adolescent Readers and Writers in Young Adult Literature and Life By Suzanne Mills Crawford A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Sarah Warshauer Freedman, Chair Professor Glynda Hull Professor Donald McQuade Fall 2012 Liars, Lovers, and Thieves: Being Adolescent Readers and Writers in Young Adult Literature and Life © 2012 by Suzanne Mills Crawford Abstract Liars, Lovers, and Thieves: Being Adolescent Readers and Writers in Young Adult Literature and Life by Suzanne Mills Crawford Doctor of Philosophy in Education University of California, Berkeley Professor Sarah Warshauer Freedman, Chair Books written for teenagers portray the lives of young people and frequently include depictions of teenagers as readers and writers. From brief mentions of writing to elaborate descriptions of reading, the representations of literacy practices contained in works of young adult literature (YAL) oftentimes bid readers to take notice. This dissertation examines representations of literacy practices in YAL and investigates the meanings that adolescent readers ascribe to them. Through analyzing a set of forty-seven award-winning texts written specifically for adolescents and through convening a book group with high school students, this two-phase research study brings together literacy, literature, and adolescents. -

Razorcake Issue #84 As A

RIP THIS PAGE OUT WHO WE ARE... Razorcake exists because of you. Whether you contributed If you wish to donate through the mail, any content that was printed in this issue, placed an ad, or are a reader: without your involvement, this magazine would not exist. We are a please rip this page out and send it to: community that defi es geographical boundaries or easy answers. Much Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc. of what you will fi nd here is open to interpretation, and that’s how we PO Box 42129 like it. Los Angeles, CA 90042 In mainstream culture the bottom line is profi t. In DIY punk the NAME: bottom line is a personal decision. We operate in an economy of favors amongst ethical, life-long enthusiasts. And we’re fucking serious about it. Profi tless and proud. ADDRESS: Th ere’s nothing more laughable than the general public’s perception of punk. Endlessly misrepresented and misunderstood. Exploited and patronized. Let the squares worry about “fi tting in.” We know who we are. Within these pages you’ll fi nd unwavering beliefs rooted in a EMAIL: culture that values growth and exploration over tired predictability. Th ere is a rumbling dissonance reverberating within the inner DONATION walls of our collective skull. Th ank you for contributing to it. AMOUNT: Razorcake/Gorsky Press, Inc., a California non-profit corporation, is registered as a charitable organization with the State of California’s COMPUTER STUFF: Secretary of State, and has been granted official tax exempt status (section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code) from the United razorcake.org/donate States IRS. -

Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO Wavelength Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies 7-1986 Wavelength (July 1986) Connie Atkinson University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength Recommended Citation Wavelength (July 1986) 69 https://scholarworks.uno.edu/wavelength/60 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies at ScholarWorks@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wavelength by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1685 C0550 EARL K. LONG LIBRARY ACQUISITIONS DEPARTMENT UNIVERSITY OF NEW ORLEANS NEW ORLEANS LA 70148 . rRINCC CUnder the - (~CRRY mooN THE FANTASY BEGINS JULY 2 "I'm not sun, but I'm almost positive, tluzt all music ~· came from New Orltans." '· -Ernie K-Doe, 1979 Features Playing in the Band ............17 New Orleans Bands ...........19 Jim Russell ....................22 Cinemox Dream Taping ....... 24 Departments July News ........... ........ 4 Cabaret ....................... 8 The Law ......................10 Reviews .................... 12 July Listings ...................26 Classified .................. ...29 Last Page ....................30 JHmlberof ~k Plobllshtr. Nau""n S S..'"' Editor. C<>nnoc Zeanah Alk<n«>n. Assorloto FAIItor. Gene S..·aramuun. Art Oindor. TIK'"""' Dnlan Ad>Ortlslna. lilo7abcch F<>nlau~e. E•letn Semcncelli. Ty~nplty. DevluVWcnrcr A'~·.nciate' Contributors, Steve Amll>nl,ccr.lvan Bndk:y. Sc Gc<>fl'C Bryan. BnbCacal••••· R>Ck Culcll\dn, Cioiml Gmady. G1n;~ GI.K.x:- tonc. N;c~ Mannclk>. Bunny Matthew.... Mclnc.ly Manco. Rtck. Oh\·ter. Hammond Scott, Durrc Scrccc. Dc"'CY Wcht> Wm ·t'h·nxth i' puhh,hctJ monthly 1n New ()rlc--..an ... -

Elements of Experiments

Elements of Experiments Ali Castleman Spring, 2012 111 -Substitution and Proliferation 2-3 -Translations and Recombinations 4-5 -Translations Extended 6-8 -Happy Accidents and Intended Randomness 9-11 -Ekphrasis, In Material, In Performance 12-14 -Whatever You Do, Don’t Stop 15-18 -The Art of Constraint 19-20 -Playing with Time, Place, and Forum 21-23 -The Art of Brevity 24-26 -Flarf Nation and Appropriation 27-34 -Possibilities in Formatting 35-41 -Aural Writing 42-44 1 Love Is Not All – Edna St. Vincent Millay Art is Not All (Mad-lib Substitution) Love is not all: it is not meat nor drink Art is not all: it is not paint nor water Nor slumber nor a roof against the rain; Nor books nor a leaf across the rain; Nor yet a floating spar to men that sink Nor yet a writing spar to light that swims And rise and sink and rise and sink again; And breathes and stops and leaves and drops again; Love can not fill the thickened lung with breath, Love can not come the dry lung among people, Nor clean the blood, nor set the fractured bone; Nor live the blood, nor set the green station wagon; Yet many a man is making friends with death Yet many a happiness is drinking wine with death Even as I speak, for lack of love alone. Even as you speak, for lack of whispers alone. It well may be that in a difficult hour, It best may dance that in a difficult winter, Pinned down by pain and moaning for release, Pinned before by time and moaning for campus, Or nagged by want past resolution's power, Yet smiled by want past statue's power, I might be driven to sell your love for peace, I might be driven to sell your hate for peace, Or trade the memory of this night for food. -

The Final Sequence

Fuck This Packet 3: The Final Sequence Packet 3: One for the Money, Two for the Show, Three for the Memorial Edition Packet by: Harris Bunker, Tony Incorvati, Alan Hettinger, Evan Suttell, Briana Magin, Stephen Bennett, Trent Koch Tossups: [Note to Moderator: Emphasize this number in the first line or say "I'm looking for a number.”] 1. On the Beatles’ album Revolver, "I'm Only Sleeping" is the this track number. A band with this number in its name made a song where the singer reminisces about "every roommate left awake by every silent scream we make" and released the song "Painkiller" on their album Human. Before asking "Excuse me miss but I can get you out of your panties," the singer of a band with this number in its name says the girl's "Tongue [is] like candy." Adam Gontier once fronted a Canadian band with this number in its name which released the songs "I Hate Everything About You" and (*) "Animal I Have Become". Yet another band with this number in its name created the song "When I'm Gone" on the same album as a song where the singer "left [his] body lyin' somewhere in the sands of time" called "Kryptonite". This number of birds sit by the singer's doorstep in a song by Bob Marley. For 10 points, identify this number found in the band name of the group that made the songs "My First Kiss" and "DONTTRUSTME" (Don't Trust Me) that along with "ABC" and 1 and 2, appeared in a Jackson 5 song. -

Targ-Sept-Web.Pdf

YukonYukon BlondeBlonde / AlvvaysAlvvays TheThe DearsDears / F****dF****d UpUp TheThe PackPack A.D.A.D. / TomTom GreenGreen TheThe ElwinsElwins / TheThe BeachesBeaches WalterWalter OstanekOstanek & more!more! OKT.OKT. 2ND2ND & 3RD3RD • VANKLEEKVANKLEEK HILLHILL FAIRGROUNDSFAIRGROUNDS WITWITHH BBUSESUSEE S FFROMROM OTOTTAWA!TAWA! WORDS FROM THE review?”° Absolutely nothing.° But I got your attention didn’t I?°No? …. *sigh*Anyhow, it’s been quite a while since a review of a classic album has WIZARD taken place so, without further ado, let’s IT’S SEPTEMBER - THE WIZARDS ARE dive into the review of SLIP IT IN by BEGINNING TO PREPARE FOR THE YEARLY BLACK FLAG. This album was put out APPRENTICE INVITATIONAL - THINGS ARE not long after MY WAR in 1984, which STARTING TO GET INTERESTING. was their fi rst dive into territory that was a far cry from their earlier sound. While DAMAGED had some song structures LET’S CHECK OUT SOME OF THIS YEAR’S EVENTS! in it which were defi nitely not typical Perogi Wizard Will has challenged Perogi Wizard Sammy to another of hardcore punk (such as DAMAGED mushroom eating competition - this yearly tradition is always a highlight I which crawled along at an extremely that we all look forward to! slow pace, but was simultaneously noisy and destructive) but the album Elixir Wizard Ula has promised a demonstration of her new water to overall, while defi nitely a standout wine enchantment, if she pulls this off her place in the book of legends is album and one of the best of its kind, ensured. was still a hardcore punk album and a crowd pleaser.