UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 #19 www.razorcake.com ight around the time we were wrapping up this issue, Todd hours on the subject and brought in visual aids: rare and and I went to West Hollywood to see the Swedish band impossible-to-find records that only I and four other people have RRRandy play. We stood around outside the club, waiting for or ancient punk zines that have moved with me through a dozen the show to start. While we were doing this, two young women apartments. Instead, I just mumbled, “It’s pretty important. I do a came up to us and asked if they could interview us for a project. punk magazine with him.” And I pointed my thumb at Todd. They looked to be about high-school age, and I guess it was for a About an hour and a half later, Randy took the stage. They class project, so we said, “Sure, we’ll do it.” launched into “Dirty Tricks,” ripped right through it, and started I don’t think they had any idea what Razorcake is, or that “Addicts of Communication” without a pause for breath. It was Todd and I are two of the founders of it. unreal. They were so tight, so perfectly in time with each other that They interviewed me first and asked me some basic their songs sounded as immaculate as the recordings. On top of questions: who’s your favorite band? How many shows do you go that, thought, they were going nuts. Jumping around, dancing like to a month? That kind of thing. -

Printz Award

Michael L. Printz Winners and Honor Books 2014 Winner: Midwinterblood by Marcus Sedgwick Honor: Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell Kingdom of Little Wounds by Susann Cokal Maggot Moon by Sally Gardner Navigating Early by Clare Vanderpool 2013 Winner: In Darkness by Nick Lake Honor: Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Sáenz Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein Dodger by Terry Pratchett The White Bicycle by Beverley Brenna 2012 Winner: Where Things Come Back by John Corey Whaley Honor: Why We Broke Up, written by Daniel Handler, art by Maira Kalman; The Returning, written by Christine Hinwood; Jasper Jones, written by Craig Silvey; The Scorpio Races, written by Maggie Stiefvater 2011 Winner: Ship Breaker by Paolo Bacigalupi Honor: Stolen by Lucy Christopher Please Ignore Vera Dietz by A.S. King Revolver written by Marcus Sedgwick Nothing written by Janne Teller 2010 Winner: Going Bovine by Libba Bray Honor: Charles and Emma: The Darwins’ Leap of Faith by Deborah Heiligman The Monstrumologist by Rick Yancey Punkzilla by Adam Rapp Tales of the Madman Underground: An Historical Romance, 1973 by John Barnes Michael L. Printz Winners and Honor Books 2009 Winner: Jellicoe Road by Melina Marchetta Honor: The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, Vol. 2: The Kingdom on the Waves by M. T. Anderson The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks by E. Lockhart Nation by Terry Pratchett Tender Morsels by Margo Lanagan 2008 Winner: The White Darkness by Geraldine McCaughrean Honor: Dreamquake: Book Two of the Dreamhunter Duet by Elizabeth Knox One Whole and Perfect Day by Judith Clarke Repossessed by A.M. -

John Zorn Artax David Cross Gourds + More J Discorder

John zorn artax david cross gourds + more J DiSCORDER Arrax by Natalie Vermeer p. 13 David Cross by Chris Eng p. 14 Gourds by Val Cormier p.l 5 John Zorn by Nou Dadoun p. 16 Hip Hop Migration by Shawn Condon p. 19 Parallela Tuesdays by Steve DiPo p.20 Colin the Mole by Tobias V p.21 Music Sucks p& Over My Shoulder p.7 Riff Raff p.8 RadioFree Press p.9 Road Worn and Weary p.9 Bucking Fullshit p.10 Panarticon p.10 Under Review p^2 Real Live Action p24 Charts pJ27 On the Dial p.28 Kickaround p.29 Datebook p!30 Yeah, it's pink. Pink and blue.You got a problem with that? Andrea Nunes made it and she drew it all pretty, so if you have a problem with that then you just come on over and we'll show you some more of her artwork until you agree that it kicks ass, sucka. © "DiSCORDER" 2002 by the Student Radio Society of the Un versify of British Columbia. All rights reserved. Circulation 17,500. Subscriptions, payable in advance to Canadian residents are $15 for one year, to residents of the USA are $15 US; $24 CDN ilsewhere. Single copies are $2 (to cover postage, of course). Please make cheques or money ordei payable to DiSCORDER Magazine, DEADLINES: Copy deadline for the December issue is Noven ber 13th. Ad space is available until November 27th and can be booked by calling Steve at 604.822 3017 ext. 3. Our rates are available upon request. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Rant & Rave Needs You!

It’s been a crazy winter so far. Snow on November 1st?! Record low temperatures?! Chances are, we’re all going to be spending a lot of time inside to try to keep out of the snow and ice. Good thing we have books to keep us company! Read on for some excellent (and weirdly excellent) suggestions from our reviewers. How does RANT & RAVE work? Four times each year, we collect book reviews from teens across Asheville and Buncombe County and publish them here. Our reviewers rate books on the following scale: Terrible Okay The Best! Beanworld: Wahoolazuma!, But that’s just the preliminary stuff you find out by Larry Marder from the back cover. There are no end of wacky stories, complex mythology, goofy words, and hilarious catchphrases. And if you look closer at the What is the book about? stories, they might just impart some great lessons This book is a graphic novel that is not like any without being moralistic or preachy in any way other comics I have ever read. Beanworld is a whatsoever. unique world that has different physics, food chains, Read this book, it is a great experience. slang, germs, everything! It takes a little getting Would you recommend this book to your friends? used to, but once you get into it, it’s great. Heck, yeah. The world is made up of eight layers, including Lasting thought you took from the book. the Thin Lake, Hoops, Twinks, and Der-stinkel. It is HOKA-HOKA GUNK-LDUNK! HOKA-HOKA populated by the “Beans,” little beanlike creatures HEY!!! who live on an island with their guardian tree, — Sagan T., 16 “Gran’Ma’Pa.” Gran’Ma’Pa grows seedish thingies called “Sprout Butts,” which they take down to RANT & RAVE NEEDS YOU! another layer populated by the “Hoi-Polloi,” Read a great book? incessant gamblers whose currency is a substance called “Chow.” The Beans steal the Chow and give Or a terrible one? the Sprout-Butts in return, which explodes into Consider sending in more Chow. -

Issue 01 One..Two...Three? Student Tests Newton’S Laws, Fails Tuesday, March 20Th

catalyst issue 01 One..Two...Three? Student Tests Newton’s Laws, Fails Tuesday, March 20th. stairs. responded Stevens when ques- A local teenager, whose and like, they were totally saying Michael Keets, a student at “I had no idea that stairs tioned about Keets’ comment, name will be kept confidential due to was completely wrong." Clark com- Spotsylvania County’s prestigious could be considered an outside “These kids never listen, especially his minor status, recently discovered mented. "I didn't like that at all." Spotsylvania Middle School, was force. I mean, according to every- Michael Keets. You tell them not to exactly how many licks it takes to get The federal government severally injured while attempting to thing else I’ve learned, they can’t be try anything we talk about in class, to the center of a Tootsie Pop. The has sided with the makers of the prove Newton’s first law of physics. a force because they have no direc- and they think you’re asking them if discovered, however, was not free of delicious treat in this case, however, Brian Stevens, the teacher who tion. They aren’t a vector quantity,” they want some cake. And they all controversy and suspicions of fraud. barring the boy from releasing his allegedly introduced Keets to said commented a heavily drugged want cake.” For years, the makers of findings, and stating that he must law, commented that he in no way Keets from his hospital bed the day Stevens also attempted to the aforementioned lollipop have revoke his press release. -

Precious but Not Precious UP-RE-CYCLING

The sounds of ideas forming , Volume 3 Alan Dunn, 22 July 2020 presents precious but not precious UP-RE-CYCLING This is the recycle tip at Clatterbridge. In February 2020, we’re dropping off some stuff when Brigitte shouts “if you get to the plastic section sharpish, someone’s throwing out a pile of records.” I leg it round and within seconds, eyes and brain honed from years in dank backrooms and charity shops, I smell good stuff. I lean inside, grabbing a pile of vinyl and sticking it up my top. There’s compilations with Blondie, Boomtown Rats and Devo and a couple of odd 2001: A Space Odyssey and Close Encounters soundtracks. COVER (VERSIONS) www.alandunn67.co.uk/coverversions.html For those that read the last text, you’ll enjoy the irony in this introduction. This story is about vinyl but not as a precious and passive hands-off medium but about using it to generate and form ideas, abusing it to paginate a digital sketchbook and continuing to be astonished by its magic. We re-enter the story, the story of the sounds of ideas forming, after the COVER (VERSIONS) exhibition in collaboration with Aidan Winterburn that brings together the ideas from July 2018 – December 2019. Staged at Leeds Beckett University, it presents the greatest hits of the first 18 months and some extracts from that first text that Aidan responds to (https://tinyurl.com/y4tza6jq), with me in turn responding back, via some ‘OUR PRICE’ style stickers with quotes/stats. For the exhibition, the mock-up sleeves fabricated by Tom Rodgers look stunning, turning the digital detournements into believable double-sided artefacts. -

Michael L. Printz Winners and Honor Books the Michael L

Michael L. Printz Winners and Honor Books The Michael L. Printz Award is an award for a book that exemplifies literary excellence in young adult literature. 2014 2010 Midwinterblood by Marcus Sedgwick Going Bovine by Libba Bray Honor Books: Honor Books: Eleanor & Park by Rainbow Rowell Charles and Emma: The Darwins’ Leap of Faith by Deborah Heiligman Kingdom of Little Wounds by Susann Cokal The Monstrumologist by Rick Yancey Maggot Moon by Sally Gardner Punkzilla by Adam Rapp Navigating Early by Clare Vanderpool Tales of the Madman Underground: An Historical Romance, 1973 by John Barnes 2013 In Darkness by Nick Lake 2009 Honor Books: Jellicoe Road by Melina Marchetta Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe by Benjamin Alire Honor Books: Sáenz The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Traitor to the Nation, Vol. 2: The Code Name Verity by Elizabeth Wein Kingdom on the Waves by M. T. Anderson Dodger by Terry Pratchett The Disreputable History of Frankie Landau-Banks by E. Lockhart The White Bicycle by Beverley Brenna Nation by Terry Pratchett Tender Morsels by Margo Lanagan 2012 Where Things Come Back by John Corey Whaley 2008 Honor Books: The White Darkness by Geraldine McCaughrean Why We Broke Up, written by Daniel Handler, art by Maira Kalman Honor Books: The Returning, written by Christine Hinwood Dreamquake: Book Two of the Dreamhunter Duet by Elizabeth Knox Jasper Jones, written by Craig Silvey One Whole and Perfect Day by Judith Clarke The Scorpio Races, written by Maggie Stiefvater Repossessed by A.M. Jenkins Your Own, Sylvia: A Verse Portrait of Sylvia Plath by Stephanie Hemphill 2011 Ship Breaker by Paolo Bacigalupi 2007 Honor Books: American Born Chinese by Gene Luen Yang Stolen by Lucy Christopher Honor Books: Please Ignore Vera Dietz by A.S. -

Dubious Voices

Dubious Voices Senior Creative Writing Project Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree Bachelor of Arts with A Major in Creative Writing at The University of North Carolina at Asheville Fall 2007 By Vicente J Hernandez Thesis Advisor Dr. Dubious Voices short stories by Vicente James Hernandez 1207 Beeston Court, Wilmington NC 28411 (910)262-6125 [email protected] Dubious Voices Hernandez 3 Contents The First Listen...................................4 Acid....................................................11 My Girlfriend's Pants .......................... 17 Secret ..................................................23 Look at the Wall ..................................27 Out......................................................31 No Thanks ...........................................43 Sign..................................................... 48 Mya's Roommate Moves Out.............. 54 Shadows ............................................. 59 I Am In Arcadia...................................76 Hernandez 4 'The First Listen" Perhaps like every other late twenty-something, white male, downtown apartment resident I was partially educated with artistic aspirations; had rich parents that inconspicuously named me Alex; and lived in debt with clothes on the floor and dishes that spent most of their time rusting in the sink. I spent most of my time planning out sculptures in my sketchbook. They were useless things that made me no money and took up space. As my brother, Jake, loved to conspicuously remind me. I lived in an apartment with him. He was younger, and I gained points for maturity but still delivered that desperate monologue hi hopes of gaining a drop of sympathy: "It was actually pretty bad. I mean I am glad I had the experience, just because it was an experience. But, based on that night, I have decided that I don't enjoy drinking plastic bottled tequila with salt on my tongue, discovering my knee is miraculously bleeding on its own, not being able to figure out or remember if I know the person driving the car. -

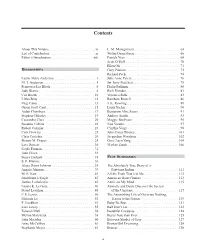

Table of Contents

Contents About This Volume . ix L . M . Montgomery . 64 List of Contributors . xi Walter Dean Myers . 66 Editor’s Introduction . xiii Patrick Ness . 68 Scott O’Dell . 70 Ellen Oh . 71 Biographies Gary Paulsen . 73 Richard Peck . 74 Laurie Halse Anderson . 3 Julie Anne Peters . 76 M . T . Anderson . 4 Sir Terry Pratchett . 78 Francesca Lia Block . 6 Philip Pullman . 80 Judy Blume . 8 Rick Riordan . 81 Coe Booth . 10 Veronica Roth . 83 Libba Bray . 12 Rainbow Rowell . 86 Meg Cabot . 13 J . K . Rowling . 88 Orson Scott Card . 15 Louis Sachar . 90 Aidan Chambers . 17 Benjamin Alire Saenz . 91 Stephen Chbosky . 19 Andrew Smith . 93 Cassandra Clare . 20 Maggie Stiefvater . 95 Suzanne Collins . 22 Ned Vizzini . 97 Robert Cormier . 23 Cynthia Voigt . 98 Cath Crowley . 25 John Corey Whaley . 101 Chris Crutcher . 26 Jacqueline Woodson . 102 Sharon M . Draper . 28 Gene Luen Yang . 104 Lois Duncan . 30 Markus Zusak . 106 Gayle Forman . 31 John Green . 33 Sonya Hartnett . 35 Plot Summaries S . E . Hinton . 36 Alaya Dawn Johnson . 38 The Absolutely True Diary of a Angela Johnson . 39 Part-time Indian . 111 M . E . Kerr . 41 All the Truth That’s in Me . 112 Madeleine L’Engle . 43 American Born Chinese . 113 Justine Larbalestier . 45 Annie on My Mind . 115 Ursula K . Le Guin . 46 Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets David Levithan . 48 of the Universe . 117 C .S . Lewis . 50 The Astonishing Life of Octavian Nothing, Malinda Lo . 51 Traitor to the Nation . 119 E . Lockhart . 53 Baby Be-Bop . 121 Lois Lowry . 55 Ball Don’t Lie . -

Printz Award Winners

Jellicoe Road How I Live Now Teen by Melina Marchetta by Meg Rosoff YF Marchetta YF Rosoff 2009. High school student Taylor 2005. To get away from her pregnant Markham, who was abandoned by stepmother in New York City, her drug-addicted mother at the age 15-year-old Daisy goes to England to Printz Award of 11, struggles with her identity and stay with her aunt and cousins, but family history at a boarding school in soon war breaks out and rips the Australia. family apart. Winners The White Darkness The First Part Last by Geraldine McCaughrean by Angela Johnson YF McCaughrean YF Johnson 2008. When her uncle takes her on a 2004. Bobby's carefree teenage life dream trip to the Antarctic changes forever when he becomes a wilderness, Sym's obsession with father and must care for his adored Captain Oates and the doomed baby daughter. expedition becomes a reality as she is soon in a fight for her life in some of the harshest terrain on the planet. Postcards from No Man's Land American Born Chinese by Aidan Chambers by Gene Luen Yang YF Chambers YGN Yang 2003. Jacob Todd travels to 2007. This graphic novel alternates Amsterdam to honor his between three stories about the grandfather, a soldier who died in a problems of young Chinese nearby town in World War II, while in Americans trying to participate in 1944, a girl named Geertrui meets an American popular culture. English soldier named Jacob Todd, who must hide with her family. The Michael L. Printz Award recognizes Looking for Alaska books that exemplify literary A Step from Heaven by John Green excellence in young adult literature YF Green by Na An 2006. -

Student Favorites (Currently) in My Classroom Library

Student Favorites (currently) in my Classroom Library History and War Forge by Laurie Halse Anderson The Boy in the Striped Pajamas by J. Boyne Shooting Kabul by N. H. Senzei Day Into Night by Anita Diamond The Hotel on the Corner of Bitter and Sweet by Jamie Ford Fallen Angels by Walter Dean Meyers Everything is Illuminated by Jonathan Safran Foer A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Hosseini War by Sebastian Junger The Good Soldiers by David Finkel Hellhound on His Trail by Hampton Sides March by Geraldine Brooks Sunrise Over Fallujah by Walter Dean Meyers Forge by Laurie Halse Anderson Copper Sun by Sharon Draper The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lachs by Rebecca Skloot Between Shades of Grey by Ruta Sepetys Never Fall Down by Patricia McCormick The Book Thief by Markus Zusak The Worst, Hard Time by Timothy Egan The Cider House Rules by John Irving Snow Falling on Cedars by David Guterson The Joy Luck Club by Amy Tan Fallen Angels by Walter Dean Myers Purple Heart by Patricia McCormick Stories from the World Behind the Beautiful Forevers by Katherine Boo They Poured Fire On Us From the Sky by Benjamin Ajak, Benson Deng, & Alephonsian Deng Sold by Patricia McCormick Trash by Andy Mulligan Cutting for Stone by Abraham Verghese A Long Way Gone by Ishmael Bea The Last Man in the Tower by Aravind Adiga Little Bee by Christopher Cleave Prisoner of Tehran by Marina Nemat Buddah in the Attic by Julie Otsuka Running the Rift by Naomi Benaren In the Land of Invisible Women by Qanta Ahmed The Attack by Yasmina Khadra The Kite Runner by Kaled Hosseini