How American Jewry Received and Responded to Technology, 1880-1965

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Menaquale, Sandy

“Prejudice is a burden that confuses the past, threatens the future, and renders the present inaccessible.” – Maya Angelou “As long as there is racial privilege, racism will never end.” – Wayne Gerard Trotman “Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.” James Baldwin “Ours is not the struggle of one day, one week, or one year. Ours is not the struggle of one judicial appointment or presidential term. Ours is the struggle of a lifetime, or maybe even many lifetimes, and each one of us in every generation must do our part.” – John Lewis COLUMBIA versus COLUMBUS • 90% of the 14,000 workers on the Central Pacific were Chinese • By 1880 over 100,000 Chinese residents in the US YELLOW PERIL https://iexaminer.org/yellow-peril-documents-historical-manifestations-of-oriental-phobia/ https://www.nytimes.com/2019/05/14/us/california-today-chinese-railroad-workers.html BACKGROUND FOR USA IMMIGRATION POLICIES • 1790 – Nationality and Citizenship • 1803 – No Immigration of any FREE “Negro, mulatto, or other persons of color” • 1848 – If we annex your territory and you remain living on it, you are a citizen • 1849 – Legislate and enforce immigration is a FEDERAL Power, not State or Local • 1854 – Negroes, Native Americans, and now Chinese may not testify against whites GERMAN IMMIGRATION https://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/FT_15.09.28_ImmigationMapsGIF.gif?w=640 TO LINCOLN’S CREDIT CIVIL WAR IMMIGRATION POLICIES • 1862 – CIVIL WAR LEGISLATION ABOUT IMMIGRATION • Message to Congress December -

1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts

EtSm „ NA 2340 A7 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from LYRASIS Members and Sloan Foundation http://archive.org/details/nationalgoldOOarch The Architectural League of Yew York 1960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of the Building Arts ichievement in the Building Arts : sponsored by: The Architectural League of New York in collaboration with: The American Craftsmen's Council held at: The Museum of Contemporary Crafts 29 West 53rd Street, New York 19, N.Y. February 25 through May 15, i960 circulated by The American Federation of Arts September i960 through September 1962 © iy6o by The Architectural League of New York. Printed by Clarke & Way, Inc., in New York. The Architectural League of New York, a national organization, was founded in 1881 "to quicken and encourage the development of the art of architecture, the arts and crafts, and to unite in fellowship the practitioners of these arts and crafts, to the end that ever-improving leadership may be developed for the nation's service." Since then it has held sixtv notable National Gold Medal Exhibitions that have symbolized achievement in the building arts. The creative work of designers throughout the country has been shown and the high qual- ity of their work, together with the unique character of The League's membership, composed of architects, engineers, muralists, sculptors, landscape architects, interior designers, craftsmen and other practi- tioners of the building arts, have made these exhibitions events of outstanding importance. The League is privileged to collaborate on The i960 National Gold Medal Exhibition of The Building Arts with The American Crafts- men's Council, the only non-profit national organization working for the benefit of the handcrafts through exhibitions, conferences, pro- duction and marketing, education and research, publications and information services. -

Madison Jewish News 4

April 2016 Adar-Nissan, 5776 Inside This Issue Jewish Federation Upcoming Events ......................5 ‘Purim Around the World’ ..................................15 Jewish Education ..........................................20-22 Simchas & Condolences ........................................6 Jewish Social Services....................................18-19 Lechayim Lights ............................................23-25 Congregation News ..........................................8-9 Business, Professional & Service Directory ............19 Israel & The World..............................................26 Jewish Federation of Madison Proposes By-Law Amendment Join us for a Meeting of the Members ish Federation of Madison’s by-laws. ports to the President and/or Board of Di- must become a Member in good stand- on Tuesday, April 19, 2016, at 7: 30 PM This paragraph currently reads: rectors, and fulfill such other advisory ing before 24 months elapse following at the Max Weinstein Jewish Community “The Board of Directors or the Presi- functions as may be designated. The des- his or her appointment in order to Building, 6434 Enterprise Lane, Madison dent may authorize, and appoint or re- ignation of such standing and/or tempo- continue committee participation. All to vote on the proposed amendment. move members of (whether or not rary committees, and the members Chairs of Committees must be members The Executive Committee of the Jew- members of the Board of Directors), thereof, shall be recorded in the minutes in good standing.” ish Federation of Madison proposes to standing and/or temporary committees to of the Board of Directors. Members of A Member is defined in the by-laws as amend Article III, Section 15 of the Jew- consider appropriate matters, make re- standing and temporary committees follows: “Every person who contributes must be Members in good standing. -

American Jewish Yearbook

JEWISH STATISTICS 277 JEWISH STATISTICS The statistics of Jews in the world rest largely upon estimates. In Russia, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and a few other countries, official figures are obtainable. In the main, however, the num- bers given are based upon estimates repeated and added to by one statistical authority after another. For the statistics given below various authorities have been consulted, among them the " Statesman's Year Book" for 1910, the English " Jewish Year Book " for 5670-71, " The Jewish Ency- clopedia," Jildische Statistik, and the Alliance Israelite Uni- verselle reports. THE UNITED STATES ESTIMATES As the census of the United States has, in accordance with the spirit of American institutions, taken no heed of the religious convictions of American citizens, whether native-born or natural- ized, all statements concerning the number of Jews living in this country are based upon estimates. The Jewish population was estimated— In 1818 by Mordecai M. Noah at 3,000 In 1824 by Solomon Etting at 6,000 In 1826 by Isaac C. Harby at 6,000 In 1840 by the American Almanac at 15,000 In 1848 by M. A. Berk at 50,000 In 1880 by Wm. B. Hackenburg at 230,257 In 1888 by Isaac Markens at 400,000 In 1897 by David Sulzberger at 937,800 In 1905 by "The Jewish Encyclopedia" at 1,508,435 In 1907 by " The American Jewish Year Book " at 1,777,185 In 1910 by " The American Je\rish Year Book" at 2,044,762 DISTRIBUTION The following table by States presents two sets of estimates. -

Leket-Israel-Passove

Leave No Crumb Behind: Leket Israel’s Cookbook for Passover & More Passover Recipes from Leket Israel Serving as the country’s National Food Bank and largest food rescue network, Leket Israel works to alleviate the problem of nutritional insecurity among Israel’s poor. With the help of over 47,000 annual volunteers, Leket Israel rescues and delivers more than 2.2 million hot meals and 30.8 million pounds of fresh produce and perishable goods to underprivileged children, families and the elderly. This nutritious and healthy food, that would have otherwise gone to waste, is redistributed to Leket’s 200 nonprofit partner organizations caring for the needy, reaching 175,000+ people each week. In order to raise awareness about food waste in Israel and Leket Israel’s solution of food rescue, we have compiled this cookbook with the help of leading food experts and chefs from Israel, the UK , North America and Australia. This book is our gift to you in appreciation for your support throughout the year. It is thanks to your generosity that Leket Israel is able to continue to rescue surplus fresh nutritious food to distribute to Israelis who need it most. Would you like to learn more about the problem of food waste? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter or visit our website (www.leket.org/en). Together, we will raise awareness, continue to rescue nutritious food, and make this Passover a better one for thousands of Israeli families. Happy Holiday and as we say in Israel – Beteavon! Table of Contents Starters 4 Apple Beet Charoset 5 Mina -

The N-Word : Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings Anne V

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2009 The N-word : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings Anne V. Benfield Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Race and Ethnicity Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Benfield, Anne V., "The -wN ord : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings" (2009). Honors Theses. 1433. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1433 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The N-Word: Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings By Anne V. Benfield * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Sociology UNION COLLEGE June, 2009 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Literature Review Etymology 7 Early Uses 8 Fluidity in the Twentieth Century 11 The Commercialization of Nigger 12 The Millennium 15 Race as a Determinant 17 Gender Binary 19 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 23 Generational Difference 25 Chapter Two: Methodology Sociological Theories 29 W.E.B DuBois’ “Double-Consciousness” 34 Qualitative Research Instrument: Focus Groups 38 Chapter Three: Results and Discussion Demographics 42 Generational Difference 43 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 47 Gender Binary 51 Race as a Determinant 55 The Ambiguity of Nigger vs. -

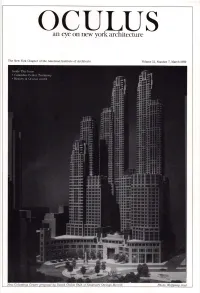

An Eye on New York Architecture

OCULUS an eye on new york architecture The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 ew Co lumbus Center proposal by David Childs FAIA of Skidmore Owings Merrill. 2 YC/AIA OC LUS OCULUS COMING CHAPTER EVENTS Volume 51, Number 7, March 1989 Oculus Tuesday, March 7. The Associates Tuesday, March 21 is Architects Lobby Acting Editor: Marian Page Committee is sponsoring a discussion on Day in Albany. The Chapter is providing Art Director: Abigail Sturges Typesetting: Steintype, Inc. Gordan Matta-Clark Trained as an bus service, which will leave the Urban Printer: The Nugent Organization architect, son of the surrealist Matta, Center at 7 am. To reserve a seat: Photographer: Stan Ri es Matta-Clark was at the center of the 838-9670. avant-garde at the end of the '60s and The New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects into the '70s. Art Historian Robert Tuesday, March 28. The Chapter is 457 Madison Avenue Pincus-Witten will be moderator of the co-sponsoring with the Italian Marble New York , New York 10022 evening. 6 pm. The Urban Center. Center a seminar on "Stone for Building 212-838-9670 838-9670. Exteriors: Designing, Specifying and Executive Committee 1988-89 Installing." 5:30-7:30 pm. The Urban Martin D. Raab FAIA, President Tuesday, March 14. The Art and Center. 838-9670. Denis G. Kuhn AIA, First Vice President Architecture and the Architects in David Castro-Blanco FAIA, Vice President Education Committees are co Tuesday, March 28. The Professional Douglas Korves AIA, Vice President Stephen P. -

Rubenfeld's Monsey Park Hotel

חג כשר ושמח! pa sso ver g r eet ing s • TOTALLY FREE CHECKING Wl'liave • BUDGET CHECKING • ISRAEL SCENIC CHECKS a bank • ALL-IN-ONE SAVINGS • CHAI BOND CERTIFICATES • TRAVEL CASH CARD for you • PERSONAL & BUSINESS LOANS MIDTOWN BROOKLYN 579 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10017 188 Montague Street, Brooklyn, N.Y. 11201 562 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10036 BRON X 301 East Fordham Road, Bronx, N.Y. 10458 WEST SIDE 1412 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10018 QUEENS 104-70 Queens Blvd., Forest Hills, N.Y. 11375 DOWNTOWN El Al Terminal, JFK Int’l. Airport 111 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10006 HEWLETT, LONG ISLAND 25 Broad Street, New York, N.Y. 10005 1280 Broadway, Hewlett, N.Y. 11557 Passover: Cantor, Seder, Services, Reserve now1 S• ■ Mg. •Glatt Kosher Cuisine Supervised by Rabbi David Cohen 4 • 3 delicious MEALS Do iMd Lis snacks) •FREE daily MASSAGE YOGA Exercise Classes NEW JERSEY־POSTURE• 3$♦ •Health Club-SAUNA,WHIRLPOOL •Heated INDOOR POOL RESORT • NfTELY DANCING* FOR YOUR HEALTH ent er t ainment •INDOOR, OUTDOOR AND PLEASURE TENNf$/GOLF available All Spa and Resort facilities Open open permitted days of Passover ALL YEAR ROUND ^Harbor Island Spa ON THE OCEAN WEST END, NEW JERSEY IELE (212)227-1051 / (201) 222-5800 Call for information & a Free Color Brochure I SUPERVISED DAY CAMP-NIGHT M.TROL נ. מ8נישעוויטץ ק8מפ8ני Genera/ Office: 340 HENDERSON STREET, JERSEY CITY, N.J. 07302 את זה תאכלו כל מיני האוכל אשר השם "מאנישעוויטץ" נקרא עליהם, כמו: ׳ מצה ותוצרת מצה וגם מצה־שמורה משעת קצירה; דנים ממולאים, מרק של בשר, עוף וירקות; חמיצות של סלק ועלי־שדה; מזון־תינוקות -

Jewish Subcultures Online: Outreach, Dating, and Marginalized Communities ______

JEWISH SUBCULTURES ONLINE: OUTREACH, DATING, AND MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies ____________________________________ By Rachel Sara Schiff Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Leila Zenderland, Chair Professor Terri Snyder, Department of American Studies Professor Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Jewish individuals use and create communities online to enrich their Jewish identity. The Internet provides Jews who do not fit within their brick and mortar communities an outlet that gives them voice, power, and sometimes anonymity. They use these websites to balance their Jewish identities and other personal identities that may or may not fit within their local Jewish community. This research was conducted through analyzing a broad range of websites. The first chapter, the introduction, describes the Jewish American population as a whole as well as the history of the Internet. The second chapter, entitled “The Black Hats of the Internet,” discusses how the Orthodox community has used the Internet to create a modern approach to outreach. It focuses in particular on the extensive web materials created by Chabad and Aish Hatorah, which offer surprisingly modern twists on traditional texts. The third chapter is about Jewish online dating. It uses JDate and other secular websites to analyze how Jewish singles are using the Internet. This chapter also suggests that the use of the Internet may have an impact on reducing interfaith marriage. The fourth chapter examines marginalized communities, focusing on the following: Jewrotica; the Jewish LGBT community including those who are “OLGBT” (Orthodox LGBT); Punk Jews; and feminist Jews. -

2006 Abstracts

Works in Progress Group in Modern Jewish Studies Session Many of us in the field of modern Jewish studies have felt the need for an active working group interested in discussing our various projects, papers, and books, particularly as we develop into more mature scholars. Even more, we want to engage other committed scholars and respond to their new projects, concerns, and methodological approaches to the study of modern Jews and Judaism, broadly construed in terms of period and place. To this end, since 2001, we have convened a “Works in Progress Group in Modern Jewish Studies” that meets yearly in connection with the Association for Jewish Studies Annual Conference on the Saturday night preceding the conference. The purpose of this group is to gather interested scholars together and review works in progress authored by members of the group and distributed and read prior to the AJS meeting. 2006 will be the sixth year of a formal meeting within which we have exchanged ideas and shared our work with peers in a casual, constructive environment. This Works in Progress Group is open to all scholars working in any discipline within the field of modern Jewish studies. We are a diverse group of scholars committed to engaging others and their works in order to further our own projects, those of our colleagues, and the critical growth of modern Jewish studies. Papers will be distributed in November. To participate in the Works in Progress Group, please contact: Todd Hasak-Lowy, email: [email protected] or Adam Shear, email: [email protected] Co-Chairs: Todd S. -

THE NEW JEWISH VOICE ■ May 2014 CEO’S Message in Praise of the “C Word” by James A

Non-profit Organization U.S. POSTAGE PAID Jewish Family Service has started 3 Permit # 428 a mentoring program, Achi, for Binghamton, NY teen boys. The JCC will hold a six-week 4 healthy-living workshop for senior adults. The film “Six Million and One” 5 will be screened as part of the community commemoration of Yom Hashoah. may 2014/iyar-sivan 5774 a publication of United jewish federation of Volume 16, Number 4 Greater Stamford, New Canaan and Darien The Little Giant Collaborative Steps for Woman’s Philanthropy Spring Dinner Federations Features Dr. Ruth By Ellen Weber during which time Westheimer Greater Stamford and WWWN Move A sage once said that “Good will share her thoughts and things come in small packages.” her life story, beginning with Forward Together At 4 foot 7 inches tall, Dr. Ruth her birth in Germany, her By Sharon Franklin with presidents of the Federations Westheimer, a world-renowned time at a school in Switzerland The UJF board unanimously voted serving as ex-officio members, will media psychologist and the where she escaped from the on March 12 to establish a “Joint evaluate opportunities for cooperation guest speaker at this year’s Holocaust, her experiences as Committee” with UJA/Federation and collaboration, and will serve as a United Jewish Federation’s a member of the Haganah as of Westport-Weston-Wilton-Norwalk central coordinator for such activity. Women’s Philanthropy Spring a Jewish freedom fighter, her (WWWN) to pursue short-term and The agreement specifically calls for Dinner, can attest to that. immigration to the United long-term collaboration. -

Marion: I Travelled from My Home in Toronto, Canada, to Brooklyn, New York, Because of Gefilte Fish

Marion: I travelled from my home in Toronto, Canada, to Brooklyn, New York, because of gefilte fish. Many Jewish foods are adored and celebrated but gefilte fish isn't one of them. Can two young authors and entrepreneurs restore its reputation? I'm Marion Kane, Food Sleuth®, and welcome to "Sittin' in the Kitchen®". Liz Alpern and Jeffrey Yoskowitz are co-authors of The Gefilte Manifesto and co-owners of The Gefilteria. Their goal is to champion Jewish foods like gefilte fish, give them a tasty makeover and earn them the respect they deserve. I first met Liz when she appeared on a panel at the Toronto Ashkenaz Festival. I knew immediately that I had to have her on my podcast. We talked at her apartment in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Marion: Let's sit down and talk Ashkenazi food - and gefilte fish in particular. I'm going to ask you to introduce yourselves. Liz: My name's Liz Alpern. I am the co-owner of The Gefilteria and co-author of The Gefilte Manifesto. Jeffrey: My name is Jeffrey Yoskowitz. I am the co-owner and chief pickler of The Gefilteria, and I am a co-author of The Gefilte Manifesto cookbook. Marion: You're both Jewish and Ashkenazi. Liz: Yes, we're both of Eastern European Jewish descent. Marion: Gefilte fish - we have to address this matter. I want to read a description of gefilte fish of the worst kind. Quote, "Bland, intractably beige, and (most unforgivably of all) suspended in jelly, the bottled version seemed to have been fashioned, golem-like, from a combination of packing material and crushed hope." Liz & Jeffrey: (laugh) Marion: That's a very unfavorable review of gefilte fish.