HG 33 Book Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political and Planning History of Delhi Date Event Colonial India 1819 Delhi Territory Divided City Into Northern and Southern Divisions

Political and Planning History of Delhi Date Event Colonial India 1819 Delhi Territory divided city into Northern and Southern divisions. Land acquisition and building of residential plots on East India Company’s lands 1824 Town Duties Committee for development of colonial quarters of Cantonment, Khyber Pass, Ridge and Civil Lines areas 1862 Delhi Municipal Commission (DMC) established under Act no. 26 of 1850 1863 Delhi Municipal Committee formed 1866 Railway lines, railway station and road links constructed 1883 First municipal committee set up 1911 Capital of colonial India shifts to Delhi 1912 Town Planning Committee constituted by colonial government with J.A. Brodie and E.L. Lutyens as members for choosing site of new capital 1914 Patrick Geddes visits Delhi and submits report on the walled city (now Old Delhi)1 1916 Establishment of Raisina Municipal Committee to provide municiap services to construction workers, became New Delhi Municipal Committee (NDMC) 1931 Capital became functional; division of roles between CPWD, NDMC, DMC2 1936 A.P. Hume publishes Report on the Relief of Congestion in Delhi (commissioned by Govt. of India) to establish an industrial colony on outskirts of Delhi3 March 2, 1937 Delhi Improvement Trust (DIT) established with A.P. Hume as Chairman to de-congest Delhi4, continued till 1951 Post-colonial India 1947 Flux of refugees in Delhi post-Independence 1948 New neighbourhoods set up in urban fringe, later called ‘greater Delhi’ 1949 Central Coordination Committee for development of greater Delhi set up under -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

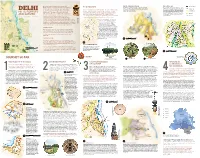

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Issue1 2012-13

Paramparā College Heritage Volunteer e-Newsletter Paramparā (Issue 1) Heritage Education and Communication Service Inaugural issue released on the World Heritage Day, 18 April 2013 Delhi’s nomination as a World Heritage City Read about INTACH’s work for Delhi’s nomination as a World 3 Heritage city. The Delhi Chapter and Heritage Education and Communication Service of INTACH have been involved in the awareness campaigns to sensitize students about Delhi’s heritage. Heritage activities undertaken in Colleges Message from the Member Secretary We are pleased to share the first issue of the INTACH HECS e- Find out about the heritage Newsletter ‘Paramparā’. The e-Newsletter showcases the efforts of activities undertaken by Gargi 5 College, Jesus and Mary College, colleges in Delhi University to promote heritage at their respective Lady Shri Ram College, Miranda educational institutions. INTACH appreciates your efforts, and thanks House and Sri Venkateswara College of Delhi University. Gargi College; Hindu College; Jesus and Mary College; Lady Shri Ram College for Women; Miranda House; St. Stephens College; and Sri Suggested Venkateswara College for their participation in the Heritage collaborative heritage activities Volunteering initiative. We thank each of you for your contributions, ideas and suggestions. It Read about the heritage activities suggested by students to be 9 would not have been possible to put together the e-Newsletter without undertaken in collaboration with INTACH. you! The first issue of the newsletter highlights the heritage activities undertaken by the Colleges in the current academic session, 2012 – 13 as well as the heritage activities being proposed for the next academic INTACH Events session. -

1 'Inhabited Pasts: Monuments, Authority and People in Delhi, 1912

‘Inhabited Pasts: Monuments, Authority and People in Delhi, 1912 – 1970s’ Abstract This article considers the relationship between the official, legislated claims of heritage conservation in India and the wide range of episodic and transitory inhabitations which have animated and transformed the monumental remains of the city, or rather cities, of Delhi. Delhi presents a spectrum of monumental structures that appear variously to either exist in splendid isolation from the rush of every day urban life or to peek out amidst a palimpsest of unplanned, urban fabric. The repeated attempts of the state archaeological authorities to disambiguate heritage from the quotidian life of the city was frustrated by bureaucratic lapse, casual social occupations and deliberate challenges. The monuments offered structural and spatial canvases for lives within the city; providing shelter, solitude and the possibility of privacy, devotional and commercial opportunity. The dominant comportment of the city’s monuments during the twentieth century has been a hybrid monumentality, in which the jealous, legislated custody of the state has become anxious, ossified and ineffectual. An acknowledgement and acceptance of the hybridity of Delhi’s monuments offers an opportunity to re-orientate understandings of urban heritage. Key words: heritage, bureaucracy, Delhi, India, monuments, AMPA 1905, urbanism, urban biography, Archaeological Survey of India. In September 2001, the Archaeological Survey of India in Delhi ruled against displays of romantic affection between couples at three large, landscaped monuments under its custody: Safdarjung’s Tomb, the Purana Qila and Lodhi Gardens. Without specifying quite how the ban would be enforced, A. C. Grover, the Survey’s media officer, warned against what he described as the ‘abuse’ of national 1 heritage by romantically demonstrative couples.1 This desire to impose codes of public conduct at Delhi’s monuments was not unprecedented. -

Introduction

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION 1. Delhi is located in northern India between the latitudes of 28°-24'-17" and 28°-53'-00" North and longitudes of 76°-50'-24" and 77°-20'-37" East. Delhi shares bordering with the States of Uttar Pradesh and Haryana. Delhi has an area of 1,483 sq. kms. Its maximum length is 51.90 kms and greatest width is 48.48 kms. 2. The Yamuna river and terminal part of the Aravali hills range are the two main geographical features of the city. The Aravali hills range are covered with forest and are called the Ridges; they are the city's lungs and help maintain its environment. The Yamuna river is Delhi's main source of drinking water and a sacred river for most of the inhabitants. 3. The average annual rainfall in Delhi is 714 mm, three-fourths of which falls in July, August and September. Heavy rainfall in the catchment area of the Yamuna can result in a dangerous flood situation for the city. During the summer months of April, May and June, temperatures can rise to 40-45 degrees Celsius; winters are typically cold with minimum temperatures during December and January falling to 4 to 5 degree Celsius. February and March, October and November are climatically the best months. 4. The forest and green cover has increased from 0.76% of total area in 1980-81 to 1.75% in 1994- 95, 5.9% in 1999, 10.2% in 2001 and 18.07% in 2003. Delhi's mineral resources are primarily sand and stone which are useful for construction activities. -

MHI-10 Urbanisation in India Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences

MHI-10 Urbanisation in India Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences Block 4 (Part 2) URBANISATION IN MEDIEVAL INDIA-1 UNIT 17 Sultanate and Its Cities 5 UNIT 18 Regional Cities 29 UNIT 19 Temple Towns in Peninsular India 63 UNIT 20 Southern Dimension : The Glory of Vijayanagara 80 UNIT 21 Sultanate Capital Cities in the Delhi Riverine Plain 105 Expert Committee Prof. B.D. Chattopadhyaya Prof. Sunil Kumar Prof. P.K. Basant Formerly Professor of History Department of History Department of History Centre for Historical Studies Delhi University, Delhi Jamia Milia Islamia, New Delhi JNU, New Delhi Prof. Swaraj Basu Prof. Amar Farooqui Prof. Janaki Nair Faculty of History Department of History Centre for Historical Studies IGNOU, New Delhi Delhi University, Delhi JNU, New Delhi Prof. Harbans Mukhia Dr. Vishwamohan Jha Prof. Rajat Datta Formerly Professor of History Atma Ram Sanatan Dharm Centre for Historical Studies Centre for Historical Studies College JNU, New Delhi JNU, New Delhi Delhi University, Delhi Prof. Lakshmi Subramanian Prof. Yogesh Sharma Prof. Abha Singh (Convenor) Centre for Studies in Social Centre for Historical Studies Faculty of History Sciences, Calcutta JNU, New Delhi IGNOU, New Delhi Kolkata Prof. Pius Malekandathil Dr. Daud Ali Centre for Historical Studies South Asia Centre JNU, New Delhi University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia Course Coordinator : Prof. Abha Singh Programme Coordinator : Prof. Swaraj Basu Block Preparation Team Unit No. Resource Person Unit No. Resource Person 17 Prof. Abha Singh 19 Prof. Abha Singh Faculty of History Faculty of History School of Social Sciences School of Social Sciences Indira Gandhi National Indira Gandhi National Open University Open University New Delhi New Delhi 20 Dr. -

Delhi Human Development Report 2006 Haryana

DELHI HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2006 HARYANA UTTAR PRADESH LEGEND DELHI HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT 2006 Partnerships for Progress Government of NCT of Delhi 1 1 YMCA Library Building, Jai Singh Road, New Delhi 110 001 Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide in Oxford New York Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto With offices in Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries. Published in India by Oxford University Press, New Delhi © Government of National Capital Territory of Delhi 2006 The moral rights of the authors have been asserted Database right Oxford University Press (maker) First published 2006 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from Oxford University Press. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer ISBN-13: 978-0-19-568362-2 ISBN-10: 0-19-568362-5 Typeset in Garamond 10/12.5 by Eleven Arts, Keshav Puram, Delhi 110 035 Printed in India by ........................... -

B.A. (Hons.) History 5 2.2

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF DELHI Delhi 110007 This document is the Revised LOCF format CBCS BA History Honours syllabus submitted on 30th July 2019 by the Department of History to the University of Delhi We would be grateful to receive your valued observations and suggestions on its contents. Please submit your responses by 15th September 2019 to <[email protected]> Professor Sunil Kumar Head, Department of History University of Delhi Sunil Kumar, Professor in the History of Medieval India Head, Department of History, University of Delhi, Delhi 110007 E-mail : [email protected] !द#ी%व'%व(ालय UNIVERSITY OF DELHI Bachelor of Arts (Hons.) History (Effective from Academic Year 2019-20) Revised Syllabus as approved by Academic Council Date: No: Executive Council Date: No: Applicable for students registered with Regular Colleges, Non Collegiate Women’s Education Board and School of Open Learning !1 List of Contents Page No. Preamble 3 1. Introduction to the Honours Programme of the History Department 4 2. Learning Outcome-based Curriculum Framework in B.A. (Hons.) in History 4 2.1. Nature and Extent of the Programme in B.A. (Hons.) History 5 2.2. Aims of Bachelor Degree Programme in B.A. (Hons.) History 5 3. Graduate Attributes in B.A. (Hons.) History 6 4. Qualification Descriptors for Graduates B.A. (Hons.) History 7 5. Programme Learning Outcomes for in B.A. (Hons.) History 7 6. Structure of B.A. (Hons.) History Programme 8 6.1. Credit Distribution for B.A. (Hons.) History 9 6.2. Semester-wise Distribution of Courses. -

Survey of Sources : Literary and Archaeological Sub Title

Survey of Sources 룂좾鲾ರಗಳ ಸಮೀಕ್ಷೆ Programme 咾ರ್ಯ响ರ ಮ BA Subject 풿ಷರ್ History and Archaeology Semester �ಕ್ಷ貾ವ鲿 III University 풿ಶ್ವ 풿ದ್ಯಾ ಲರ್ Karnatak University, Dharwad Session ಅವ鲿 2 Title : Survey of Sources : Literary and Archaeological Sub Title: Archaeological sources Learning Objectives To expose learners different sources to the study of History Session Out Comes Students will understand the Importance of the Archaeological sources to reconstruct History Archaeological Sources • Archaeology means study of material remains. • Archaeological sources are as essential as literary sources. • Archaeological sources are classified as Archaeological Sources Epigraphy Numismatics Monuments (Inscriptions) (Coins) Important Inscription 1. Bagapalli Inscription of Harihara-I 1336- Establishment of Vijayanagara Empire 2. Nellur Copper Plate (Changalpet district) of Harihara I 1339 – titles of Harihara I Raj Rajadhiraj Parmeshwara. 3. Shravanabelagola Inscription of Bukkaraya -II-1368 A.D. it gives information of Religious Conflicts between Jainas and Vaishnavas. 4. Bitragunt (Nellur district) 1356. about five Sangama brothers and genealogy of Sanagam dynasty. 5. Channarayapattana (Hasan district) inscription of Harihara II describes about the Bukkaraya after his victory he made Vijaya as his capital. Important Inscription……. 6. Chikkaballapur Inscription of Devaraya-II--1432 A.D it stated about the marriage system of that period. 7. Shrirangam inscription of Devaraya II 1434- Vijayanagara geneology and the Taxation system of Sangama dynasty. 8. Devulpalli (Chittor district) inscription of Narsimha II 1504- Salva dynasty. 9.Kandiyan Tandal (North Arcot) inscription of Virnarsimha 1507- Tuluva dynasty, geneology and achievements of Narsimha . 10. Hampi (Bellary district) inscription of Krishnadevaraya 1510- it is in Sanskrit & Kannada language it states about donartiongiven by Krishnadevaraya at the time of coronation and the relation between Gajapti ruler of Orissa and Krishnadevaraya. -

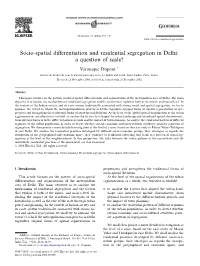

Socio-Spatial Differentiation and Residential Segregation in Delhi: a Question of Scale?

Geoforum 35 (2004) 157–175 www.elsevier.com/locate/geoforum Socio-spatial differentiation and residential segregation in Delhi: a question of scale? Veronique Dupont * Institut de Recherche pour le Developpment & Centre for Indian and South Asian Studies, Paris, France Received 21 November 2001; received in revised form 28 December 2002 Abstract This paper focuses on the pattern of social-spatial differentiation and segmentation of the metropolitan area of Delhi. The main objective is to analyse the mechanisms of residential segregation and the factors that explain it both at the micro- and macro-level. In the context of the Indian society and its caste system traditionally associated with strong social and spatial segregation, we try to appraise the extent to which the metropolitanization process in Delhi engenders original forms of spatial segmentation or per- petuates and strengthens the traditional forms of socio-spatial divisions. At the level of the global spatial organization of the urban agglomeration, our objective is twofold: to analyse the factors that shaped the urban landscape and introduced spatial discontinuity, from physical barriers to the different historic periods and the impact of town planning; to analyse the residential pattern of different segments of the urban population, in order to detect whether certain economic and socio-cultural attributes generate a pattern of segregation. We then pursue a more detailed investigation at the level of a zone, based on the case study of Mayur Vihar–Trilokpuri in east Delhi. We analyse the residential practices developed by different socio-economic groups, their strategies as regards the occupation of the geographical and economic space, their tendency to residential clustering that leads to a pattern of social seg- regation at the level of the neighbourhood.