1 'Inhabited Pasts: Monuments, Authority and People in Delhi, 1912

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lodi Garden-A Historical Detour

Aditya Singh Rathod Subject: Soicial Science] [I.F. 5.761] Vol. 8, Issue: 6, June: 2020 International Journal of Research in Humanities & Soc. Sciences ISSN:(P) 2347-5404 ISSN:(O)2320 771X Lodi Garden-A Historical Detour ADITYA SINGH RATHOD Department of History University of Delhi, Delhi Lodi Garden, as a closed complex comprises of several architectural accomplishments such as tombs of Muhammad Shah and Sikandar Lodi, Bara Gumbad, Shish Gumbad (which is actually tomb of Bahlul Lodi), Athpula and many nameless mosque, however my field work primarily focuses upon the monuments constructed during the Lodi period. This term paper attempts to situate these monuments in the context of their socio-economic and political scenario through assistance of Waqiat-i-Mushtaqui and tries to traverse beyond the debate of sovereignty, which they have been confined within all these years. Village of Khairpur was the location of some of the tombs, mosques and other structures associated with the Lodi period, however in 1936; villagers were deported out of this space to lay the foundation of a closed campus named as Lady Willingdon Park, in the commemoration of erstwhile viceroy’s wife; later which was redesigned by eminent architect, J A Stein and was renamed as Lodi Garden in 1968. Its proximity to the Dargah of Shaykh Nizamuddin Auliya delineated Sufi jurisdiction over this space however, in due course of time it came under the Shia influence as Aliganj located nearby to it, houses monuments subscribing to this sect, such as Gateway of Old Karbala and Imambara; even the tomb of a powerful Shia Mughal governor i.e. -

Basic Statistics of Delhi

BASIC STATISTICS OF DELHI Page No. 1. Names of colonies/properties, structures and gates in Eighteenth Century 2 1.1 Sheet No.1 Plan of the City of Delhi 2 1.2 Sheet No.2 Plan of the City of Delhi 2 1.3 Sheet No.5 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.4 Sheet No.7 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.5 Sheet No.8 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.6 Sheet No.9 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.7 Sheet No.11 Plan of the City of Delhi 3 1.8 Sheet No.12 Plan of the City of Delhi 4 2. List of built up residential areas prior to 1962 4 3. Industrial areas in Delhi since 1950’s. 5 4. Commercial Areas 6 5. Residential Areas – Plotted & Group Housing Residential colonies 6 6. Resettlement Colonies 7 7. Transit Camps constructed by DDA 7 8. Tenements constructed by DDA/other bodies for Slum Dwellers 7 9. Group Housing constructed by DDA in Urbanized Villages including on 8 their peripheries up to 1980’s 10. Colonies developed by Ministry of Rehabilitation 8 11. Residential & Industrial Development with the help of Co-op. 8 House Building Societies (Plotted & Group Housing) 12. Institutional Areas 9 13. Important Stadiums 9 14. Important Ecological Parks & other sites 9 15. Integrated Freight Complexes-cum-Wholesale markets 9 16. Gaon Sabha Land in Delhi 10 17. List of Urban Villages 11 18. List of Rural Villages 19. List of 600 Regularized Unauthorized colonies 20. -

Political and Planning History of Delhi Date Event Colonial India 1819 Delhi Territory Divided City Into Northern and Southern Divisions

Political and Planning History of Delhi Date Event Colonial India 1819 Delhi Territory divided city into Northern and Southern divisions. Land acquisition and building of residential plots on East India Company’s lands 1824 Town Duties Committee for development of colonial quarters of Cantonment, Khyber Pass, Ridge and Civil Lines areas 1862 Delhi Municipal Commission (DMC) established under Act no. 26 of 1850 1863 Delhi Municipal Committee formed 1866 Railway lines, railway station and road links constructed 1883 First municipal committee set up 1911 Capital of colonial India shifts to Delhi 1912 Town Planning Committee constituted by colonial government with J.A. Brodie and E.L. Lutyens as members for choosing site of new capital 1914 Patrick Geddes visits Delhi and submits report on the walled city (now Old Delhi)1 1916 Establishment of Raisina Municipal Committee to provide municiap services to construction workers, became New Delhi Municipal Committee (NDMC) 1931 Capital became functional; division of roles between CPWD, NDMC, DMC2 1936 A.P. Hume publishes Report on the Relief of Congestion in Delhi (commissioned by Govt. of India) to establish an industrial colony on outskirts of Delhi3 March 2, 1937 Delhi Improvement Trust (DIT) established with A.P. Hume as Chairman to de-congest Delhi4, continued till 1951 Post-colonial India 1947 Flux of refugees in Delhi post-Independence 1948 New neighbourhoods set up in urban fringe, later called ‘greater Delhi’ 1949 Central Coordination Committee for development of greater Delhi set up under -

Download Feroz Shah Kotla Fort

Feroz Shah Kotla Fort Feroz Shah Kotla Fort, Delhi Feroz Shah Kotla Fort was built by Feroz Shah Tughlaq in New Delhi. There are many inscriptions in different monuments of the fort which were built since the Mauryan period. Ashokan Pillar was brought here from Haryana and installed in a pyramid shaped building. The fort also has a mosque which is considered as the oldest mosque in India. This tutorial will let you know about the history of the fort along with the structures present inside. You will also get the information about the best time to visit it along with how to reach the fort. Audience This tutorial is designed for the people who would like to know about the history of Feroz Shah Kotla Fort along with the interiors and design of the fort. This fort is visited by many people from India. Prerequisites This is a brief tutorial designed only for informational purpose. There are no prerequisites as such. All that you should have is a keen interest to explore new places and experience their charm. Copyright & Disclaimer Copyright 2016 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute, or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Conceptual Plan

Expansion of “V3S East Centre” (Commercial Complex) at Laxmi Nagar by “V3S Infratech Limited” SECTION C: CONCEPTUAL PLAN Environmental Consultant: Perfact EnviroSolutions Pvt. Ltd. C-1 Expansion of “V3S East Centre” (Commercial Complex) at Laxmi Nagar by “V3S Infratech Limited” 1. Introduction The proposed project is Expansion of “V3S East Centre” which is located at Plot No. 12, Laxmi Nagar, District Centre, New Delhi by M/s V3S Infratech Limited. The complex is an already operational project and has been developed as per Environmental Clearance vide letter no. 21-708/2006-IA.III dated 08.08.2007 to M/s YMC Buildmore Pvt. Ltd. for plot area of 2 2 12540 m and built-up area of 39093.140 m . After that M/s YMC Buildmore Pvt. Ltd. has amalgamated with M/s Gahoi Buildwell Ltd. by Ministry of Corporate Affairs O/O Registrar of Companies NCT of Delhi and Haryana on 24th April 2008 . Then name of M/s Gahoi Buildwell Ltd changed to M/s V3S Infratech Limited on 27th November 2009 by Govt. of India- Ministry of Corporate Affairs, Registrar of Companies Maharastra , Mumbai. 2 Project is operational with built up area 38994.95 m . Now due to amendment in UBBL Bye Laws, FAR is being shifted to Non-FAR and vertical expansion has been proposed. The built 2 up area of the project will be 38994.95 m² to 43585.809 m . Hence, we are applying for Expansion of the project. 1.2 Type of Project The proposed project is expansion of existing V3S East Centre (Commercial Complex). -

The Delhi Sultans

The Delhi Sultans Question 1. Rudramadevi ruled Kakatiya dynasty from: (a) 1262 to 1289 (b) 1130-1145 (c) 1165-1192 (d) 1414-1451 Answer Answer: (a) 1262 to 1289 Question 2. The Delhi Sultans were dependent upon: (a) Trade, tribute or plunder for supplies (b) Taxes from tourists (c) Taxes from Artisans (d) None Answer Answer: (a) Trade, tribute or plunder for supplies Question 3. Name of the first mosque built by Sultans in Delhi is: (a) JamaMasjid (b) Moth ki Masjid (c) Quwwat al-Islam (d) Jamali Kamali Masjid Answer Answer: (c) Quwwat al-Islam Question 4. Who built the mosque Quwwat al-Islam? (a) Ghiyasuddin Balban (b) Iltutmish (c) Raziyya Sultan (d) Alauddin Khalji Answer Answer: (b) Iltutmish Question 5. Which mosque is “Sanctuary of the World”? (a) Begumpuri Mosque (b) Moth Mosque (c) Neeli Mosque (d) Jamali Kamali Mosque Answer Answer: (a) Begumpuri Mosque Question 6. Ziyauddin Barani was: (a) An archaeologist; (b) A warrior; (c) Sultan (d) A Muslim political thinker of the Delhi Sultanate Answer Answer: (d) A Muslim political thinker of the Delhi Sultanate Question 7. Ibn Battuta belonged from: (a) Iran (b) Morocco (c) Afghanistan (d) China Answer Answer: (b) Morocco Question 8. Sher Shah Suri started his career as: (a) Accountant (b) Soldier (c) Manager (d) Traveller Answer Answer: (c) Manager Question 9. Ghiyasuddin Balban was Sultan of dynasty: (a) Khalji (b) Tughluq (c) Sayyid (d) Turkish Answer Answer: (b) Tughluq Question 10. A Garrison town is: (а) A fortified settlement, with soldiers (b) A settlement of peasants (c) A settlement of ruler (d) A settlement of town where special river was carried Answer Answer: (а) A fortified settlement, with soldiers Question 11. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

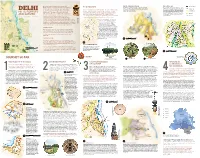

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Issue1 2012-13

Paramparā College Heritage Volunteer e-Newsletter Paramparā (Issue 1) Heritage Education and Communication Service Inaugural issue released on the World Heritage Day, 18 April 2013 Delhi’s nomination as a World Heritage City Read about INTACH’s work for Delhi’s nomination as a World 3 Heritage city. The Delhi Chapter and Heritage Education and Communication Service of INTACH have been involved in the awareness campaigns to sensitize students about Delhi’s heritage. Heritage activities undertaken in Colleges Message from the Member Secretary We are pleased to share the first issue of the INTACH HECS e- Find out about the heritage Newsletter ‘Paramparā’. The e-Newsletter showcases the efforts of activities undertaken by Gargi 5 College, Jesus and Mary College, colleges in Delhi University to promote heritage at their respective Lady Shri Ram College, Miranda educational institutions. INTACH appreciates your efforts, and thanks House and Sri Venkateswara College of Delhi University. Gargi College; Hindu College; Jesus and Mary College; Lady Shri Ram College for Women; Miranda House; St. Stephens College; and Sri Suggested Venkateswara College for their participation in the Heritage collaborative heritage activities Volunteering initiative. We thank each of you for your contributions, ideas and suggestions. It Read about the heritage activities suggested by students to be 9 would not have been possible to put together the e-Newsletter without undertaken in collaboration with INTACH. you! The first issue of the newsletter highlights the heritage activities undertaken by the Colleges in the current academic session, 2012 – 13 as well as the heritage activities being proposed for the next academic INTACH Events session. -

Mosque Architecture in Delhi : Continuity and Change in Its Morphology

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267627164 MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE IN DELHI : CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN ITS MORPHOLOGY Article · December 2012 DOI: 10.13140/2.1.2372.7042 CITATIONS READS 0 1,103 1 author: Asif Ali Aligarh Muslim University 17 PUBLICATIONS 20 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Development of Mosque Architecture in North India and its Influence on Malaysian Mosques View project Virtual Archeology View project All content following this page was uploaded by Asif Ali on 01 November 2014. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE IN DELHI : CONTINUITY AND CHANGE IN ITS MORPHOLOGY Asif Ali* ABSTRACT This paper presents the summary of a recently completed dissertation by the author keeping in view the objectives viz. 1) to study and identify the essential elements of the mosque, their meanings and their functions, 2) to study the evolution of the mosque architecture in Delhi from early Islamic period to present time and 3) to identify and establish the continuity and the change in the morphology of the mosque in Delhi and the factors which influenced its development through time. To answer the research question and to accomplish the objectives mentioned above, following methodologies were adopted. In order to view the continuity and changes in the mosque architecture in Delhi, it seemed essential to study their historical enquiry. It was not only the survey of the historical mosque but the approach was to understand the future of mosque architecture through their past. -

The Age of Akbar

CHAPTER 3 THE AGE OF AKBAR MUGHAL THEORIES OF KINGSHIP AND STATE POLITY Akbar is generally recognized as the greatest and most capable of the Mughal rulers. Under him Mughal polity and statecraft reached maturity; and under his guidance the Mughals changed from a petty power to a major dynastic state. From his time to the end of the Mughal period, artistic production on both an imperial and sub-imperial level was closely linked to notions of state polity, religion and kingship. Humayun died in 1556, only one year after his return to Hindustan. Upon hearing the call to prayers, he slipped on the steep stone steps of the library in his Din-Panah citadel in Delhi. Humayun's only surviving son and heir- apparent, Akbar, then just fourteen years of age, ascended the throne and ruled until 1605 the expanding Mughal empire. Until about 1561, Akbar was under the control of powerful court factions, first his guardian, Bhairam Khan, and then the scheming Maham Anga, a former imperial wet-nurse. Between about 1560 and 1580, Akbar devoted his energies to the conquest and then the con- solidation of territory in north India. This he achieved through battle, marriage, treaty and, most significantly, administrative reform. Concurrent with these activities, Akbar developed an interest in religion that, while initially a personal concern, ultimately transformed his concept of state. Many of the policies he adopted, such as the renunciation of the poll-tax (jiziya) for non- Muslims, had a solid political basis as well as a personal one, for Akbar, much more than his Mughal predecessors, saw every advantage in maintaining good relations with the Hindu majority.