Delhi Human Development Report 2006 Haryana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political and Planning History of Delhi Date Event Colonial India 1819 Delhi Territory Divided City Into Northern and Southern Divisions

Political and Planning History of Delhi Date Event Colonial India 1819 Delhi Territory divided city into Northern and Southern divisions. Land acquisition and building of residential plots on East India Company’s lands 1824 Town Duties Committee for development of colonial quarters of Cantonment, Khyber Pass, Ridge and Civil Lines areas 1862 Delhi Municipal Commission (DMC) established under Act no. 26 of 1850 1863 Delhi Municipal Committee formed 1866 Railway lines, railway station and road links constructed 1883 First municipal committee set up 1911 Capital of colonial India shifts to Delhi 1912 Town Planning Committee constituted by colonial government with J.A. Brodie and E.L. Lutyens as members for choosing site of new capital 1914 Patrick Geddes visits Delhi and submits report on the walled city (now Old Delhi)1 1916 Establishment of Raisina Municipal Committee to provide municiap services to construction workers, became New Delhi Municipal Committee (NDMC) 1931 Capital became functional; division of roles between CPWD, NDMC, DMC2 1936 A.P. Hume publishes Report on the Relief of Congestion in Delhi (commissioned by Govt. of India) to establish an industrial colony on outskirts of Delhi3 March 2, 1937 Delhi Improvement Trust (DIT) established with A.P. Hume as Chairman to de-congest Delhi4, continued till 1951 Post-colonial India 1947 Flux of refugees in Delhi post-Independence 1948 New neighbourhoods set up in urban fringe, later called ‘greater Delhi’ 1949 Central Coordination Committee for development of greater Delhi set up under -

Download Feroz Shah Kotla Fort

Feroz Shah Kotla Fort Feroz Shah Kotla Fort, Delhi Feroz Shah Kotla Fort was built by Feroz Shah Tughlaq in New Delhi. There are many inscriptions in different monuments of the fort which were built since the Mauryan period. Ashokan Pillar was brought here from Haryana and installed in a pyramid shaped building. The fort also has a mosque which is considered as the oldest mosque in India. This tutorial will let you know about the history of the fort along with the structures present inside. You will also get the information about the best time to visit it along with how to reach the fort. Audience This tutorial is designed for the people who would like to know about the history of Feroz Shah Kotla Fort along with the interiors and design of the fort. This fort is visited by many people from India. Prerequisites This is a brief tutorial designed only for informational purpose. There are no prerequisites as such. All that you should have is a keen interest to explore new places and experience their charm. Copyright & Disclaimer Copyright 2016 by Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. All the content and graphics published in this e-book are the property of Tutorials Point (I) Pvt. Ltd. The user of this e-book is prohibited to reuse, retain, copy, distribute, or republish any contents or a part of contents of this e-book in any manner without written consent of the publisher. We strive to update the contents of our website and tutorials as timely and as precisely as possible, however, the contents may contain inaccuracies or errors. -

INFORMATION to USERS the Most Advanced Technology Has Been Used to Photo Graph and Reproduce This Manuscript from the Microfilm Master

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" X 9" black and w h itephotographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing the World'sUMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 8824569 The architecture of Firuz Shah Tughluq McKibben, William Jeffrey, Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by McKibben, William Jeflfrey. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, MI 48106 PLEASE NOTE: In all cases this material has been filmed in the best possible way from the available copy. -

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India

Remembering Partition: Violence, Nationalism and History in India Gyanendra Pandey CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Remembering Partition Violence, Nationalism and History in India Through an investigation of the violence that marked the partition of British India in 1947, this book analyses questions of history and mem- ory, the nationalisation of populations and their pasts, and the ways in which violent events are remembered (or forgotten) in order to en- sure the unity of the collective subject – community or nation. Stressing the continuous entanglement of ‘event’ and ‘interpretation’, the author emphasises both the enormity of the violence of 1947 and its shifting meanings and contours. The book provides a sustained critique of the procedures of history-writing and nationalist myth-making on the ques- tion of violence, and examines how local forms of sociality are consti- tuted and reconstituted by the experience and representation of violent events. It concludes with a comment on the different kinds of political community that may still be imagined even in the wake of Partition and events like it. GYANENDRA PANDEY is Professor of Anthropology and History at Johns Hopkins University. He was a founder member of the Subaltern Studies group and is the author of many publications including The Con- struction of Communalism in Colonial North India (1990) and, as editor, Hindus and Others: the Question of Identity in India Today (1993). This page intentionally left blank Contemporary South Asia 7 Editorial board Jan Breman, G.P. Hawthorn, Ayesha Jalal, Patricia Jeffery, Atul Kohli Contemporary South Asia has been established to publish books on the politics, society and culture of South Asia since 1947. -

JOURNEY SO FAR of the River Drain Towards East Water

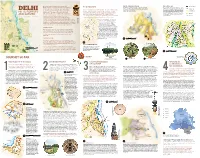

n a fast growing city, the place of nature is very DELHI WITH ITS GEOGRAPHICAL DIVISIONS DELHI MASTER PLAN 1962 THE REGION PROTECTED FOREST Ichallenging. On one hand, it forms the core framework Based on the geology and the geomorphology, the region of the city of Delhi The first ever Master plan for an Indian city after independence based on which the city develops while on the other can be broadly divided into four parts - Kohi (hills) which comprises the hills of envisioned the city with a green infrastructure of hierarchal open REGIONAL PARK Spurs of Aravalli (known as Ridge in Delhi)—the oldest fold mountains Aravalli, Bangar (main land), Khadar (sandy alluvium) along the river Yamuna spaces which were multi functional – Regional parks, Protected DELHI hand, it faces serious challenges in the realm of urban and Dabar (low lying area/ flood plains). greens, Heritage greens, and District parks and Neighborhood CULTIVATED LAND in India—and river Yamuna—a tributary of river Ganga—are two development. The research document attempts to parks. It also included the settlement of East Delhi in its purview. HILLS, FORESTS natural features which frame the triangular alluvial region. While construct a perspective to recognize the role and value Moreover the plan also suggested various conservation measures GREENBELT there was a scattering of settlements in the region, the urban and buffer zones for the protection of river Yamuna, its flood AND A RIVER of nature in making our cities more livable. On the way, settlements of Delhi developed, more profoundly, around the eleventh plains and Ridge forest. -

Issue1 2012-13

Paramparā College Heritage Volunteer e-Newsletter Paramparā (Issue 1) Heritage Education and Communication Service Inaugural issue released on the World Heritage Day, 18 April 2013 Delhi’s nomination as a World Heritage City Read about INTACH’s work for Delhi’s nomination as a World 3 Heritage city. The Delhi Chapter and Heritage Education and Communication Service of INTACH have been involved in the awareness campaigns to sensitize students about Delhi’s heritage. Heritage activities undertaken in Colleges Message from the Member Secretary We are pleased to share the first issue of the INTACH HECS e- Find out about the heritage Newsletter ‘Paramparā’. The e-Newsletter showcases the efforts of activities undertaken by Gargi 5 College, Jesus and Mary College, colleges in Delhi University to promote heritage at their respective Lady Shri Ram College, Miranda educational institutions. INTACH appreciates your efforts, and thanks House and Sri Venkateswara College of Delhi University. Gargi College; Hindu College; Jesus and Mary College; Lady Shri Ram College for Women; Miranda House; St. Stephens College; and Sri Suggested Venkateswara College for their participation in the Heritage collaborative heritage activities Volunteering initiative. We thank each of you for your contributions, ideas and suggestions. It Read about the heritage activities suggested by students to be 9 would not have been possible to put together the e-Newsletter without undertaken in collaboration with INTACH. you! The first issue of the newsletter highlights the heritage activities undertaken by the Colleges in the current academic session, 2012 – 13 as well as the heritage activities being proposed for the next academic INTACH Events session. -

1 'Inhabited Pasts: Monuments, Authority and People in Delhi, 1912

‘Inhabited Pasts: Monuments, Authority and People in Delhi, 1912 – 1970s’ Abstract This article considers the relationship between the official, legislated claims of heritage conservation in India and the wide range of episodic and transitory inhabitations which have animated and transformed the monumental remains of the city, or rather cities, of Delhi. Delhi presents a spectrum of monumental structures that appear variously to either exist in splendid isolation from the rush of every day urban life or to peek out amidst a palimpsest of unplanned, urban fabric. The repeated attempts of the state archaeological authorities to disambiguate heritage from the quotidian life of the city was frustrated by bureaucratic lapse, casual social occupations and deliberate challenges. The monuments offered structural and spatial canvases for lives within the city; providing shelter, solitude and the possibility of privacy, devotional and commercial opportunity. The dominant comportment of the city’s monuments during the twentieth century has been a hybrid monumentality, in which the jealous, legislated custody of the state has become anxious, ossified and ineffectual. An acknowledgement and acceptance of the hybridity of Delhi’s monuments offers an opportunity to re-orientate understandings of urban heritage. Key words: heritage, bureaucracy, Delhi, India, monuments, AMPA 1905, urbanism, urban biography, Archaeological Survey of India. In September 2001, the Archaeological Survey of India in Delhi ruled against displays of romantic affection between couples at three large, landscaped monuments under its custody: Safdarjung’s Tomb, the Purana Qila and Lodhi Gardens. Without specifying quite how the ban would be enforced, A. C. Grover, the Survey’s media officer, warned against what he described as the ‘abuse’ of national 1 heritage by romantically demonstrative couples.1 This desire to impose codes of public conduct at Delhi’s monuments was not unprecedented. -

ANSWERED ON:07.12.2015 E-Ticketing for Monuments Mishra Shri Anoop;Rao Shri Rayapati Sambasiva

GOVERNMENT OF INDIA CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO:1352 ANSWERED ON:07.12.2015 E-Ticketing for Monuments Mishra Shri Anoop;Rao Shri Rayapati Sambasiva Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF CULTURE LOK SABHA UNSTARRED QUESTION NO.1352 TO BE ANSWERED ON 7.12.2015 AGRAHAYANA 16, 1937 (SAKA) E-TICKETING FOR MONUMENTS +1352. SHRI ANOOP MISHRA: SHRI RAYAPATI SAMBASIVA RAO: Will the Minister of CULTURE be pleased to state: (a) whether the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) proposes to introduce e-ticketing system for entry into protected monuments in the country; (b) if so, the details thereof and the time by which the said proposal is likely to be implemented; (c) if not, the reasons therefor; (d) whether the Government has taken any steps to increase the revenue from the ticketed monuments in the country; and (e) if so, the details thereof along with the details of revenue generated from each such monument, State-wise and monument-wise? Answer ANSWER MINISTER OF STATE, CULTURE AND TOURISM (INDEPENDENT CHARGE) AND MINISTER OF STATE, CIVIL AVIATION (DR. MAHESH SHARMA) (a)to(c) Yes, Madam. Archaeological Survey of India has launched e-ticketing services at Taj Mahal, Agra and a few monuments of Delhi. E-ticketing services will be launched at all ticketed monuments shortly. (d) Enhancement in entry fee at centrally protected ticketed monuments and charges of license fee for filming operations in the centrally protected monuments have been made vide Gazette Notification No.G.S.R. 607(E) dated 31st July, 2015. -

Delhi Tourism Hoho Bus Service

International Journal of Advance and Innovative Research Volume 1, Issue 1 : October - December, 2014 AN INNOVATIVE SERVICE - DELHI TOURISM HOHO BUS SERVICE Tazyn Rahman ABSTRACT The tourism industry in India is substantial and vibrant, and the country is fast becoming a major global destination. India’s travel and tourism industry is one of most profitable industries in the country, and also credited with contributing a substantial amount of foreign exchange. Tourism contributes 6.23% to the national GDP and 8.78% of the total employment in India. The tourism industry in India generated about US$100 billion in 2008 and that is expected to increase to US$275.5 billion by 2018 at a 9.4% annual growth rate. Delhi, the capital of India has a rich cultural heritage and a variety of tourist attractions. To boost tourism in Delhi, Delhi Tourism & Transportation Development Corporation Ltd (DTTDC) was set up by the Delhi government. It initiates lot of marketing and promotional activities to boost tourism in recent years. Recently DTTDC have introduced a unique bus service (HOHO) under Public Private Initiative. The “hop-on, hop off” bus service, commonly known as “HOHO” service, is just the perfect answer to sightseeing in Delhi. One can plan and explore the city at his convenience. The tourists can avail of the hop-on, hop-off bus service to visit historical monuments, museums and other tourist hotspots in the city. This paper tries to analyse the opportunities and service offered by HOHO bus. The article also gives some suggestions that can be used in forming a right strategy to promote Delhi tourism as an attractive tourism destination on the domestic and international platform. -

Tour-Brochure.Pdf

Starting Rs 1099 DELHI HOP ON HOP OFF TOUR HARIDWAR Places: Gurudwara Bangla Sahib What to Expect: RISHIKESH Rashtrapati Bhawan Hop On Hop Off Tour Red Fort 20+ Tourist Amber Fort Jama Masjid Raj Ghat Attractions: Hawa Mahal ONE DAY TOUR Doll Museum 1 Day & 2 Days Tour Feroz Shah Kotla Fort Pass Places: What to Expect: Doll Museum Daily Service, Except At Rishikesh -Lakshman Haridwar-Rishikesh NGMA Monday Jhoola Tour India Gate 7:30 am to 7:00 pm Rajpath Drive Pass Ram Jhoola Dep. Mon, Wed, Fri Onboard Guest National Museum Shivananda Ashram 21:30 hrs to Arr. Relation Executive Nehru Museum Rameshwar Temple Next Day 22:30 hrs Rail Museum Live Commentary Dilli Haat Geeta Bhawan Breakfast, Lunch, Qutab Minar Bus Features: Yoga Training Centre Dinner Halt Lotus Temple Low Floor Bus Humayun's Tomb Air Conditioned Purana Qila At Haridwar - Holy Bath at Bus Features: Delhi Zoo GPS Enabled Harkipauri AC Coach Jantar Mantar 45 Minutes Mansa-Devi Temple Push Back Seats Madame Tussaud's Wax Museums Frequency Jal Mahal Qutab Minar Starting Rs 499 JAIPUR Starting Rs 1250 ONE DAY TOUR Lakshman Jhula What to Expect: Places: Jaipur Sightseeing Amber Fort Jaipur Shopping Birla Mandir Onboard Guest Red Fort Hawa Mahal (Drive Pass) Relation Executive Jal Mahal (Drive Pass) Breakfast, Lunch, Jantar Mantar Dinner Halt City Palace Departure @ 6 am Return by 11:30 pm Bus Features: AC Tempo Traveler Push Back Seats India Gate Haridwar Harki Pauri AGRA ONE DAY TOUR PRASANNA PURPLE MOBILITY Places: What to Expect: SOLUTIONS PVT. LTD. Taj Mahal Same Day Tour Agra -

Nd City No Tour of Delhi Is Complete Without an Understanding of Our

Walk 1 - Sultanate Delhi 1st City No introduction to Delhi is complete without this Sultanate Delhi tour. Here we’ll walk the 1st City of Delhi to unearth layers of history and architectural forms in the Qutb complex. If time permits, we’ll also walk the Mehrauli Archeological Park to discover the ruins, including baoli-wells (stepwells), a flourishing green Delhi with birds, trees & butterflies. Walk 2 – Siri, 2nd City From Walk 1, the name of the Sultan Alai-ud din Khilji will be familiar to you all. He not only built many buildings in the Qutb complex but created the 2nd City of Delhi. The ruins of this city lie not far from the first city, around the Shahpur Jat village. Walk 3 – Spiritual Delhi No tour of Delhi is complete without an understanding of our religious culture. In this spiritual tour we visit three temples: a Hindu, a Jain and a Sikh temple, and a mosque to witness and discuss the various forms of religious practice and meditations, all in Chandni Chowk on one street and so close to one another. Once familiar with the do & don’ts at religious sites feel at ease to visit places in your vicinity. In our Advanced Walk series, join the Meeting of the Faiths walk to explore the umpteen layers of multi-faceted religious Delhi. Walk 4 – Tughlakabad: 3rd City Let’s walk the ruins of Tughlakabad, the 3rd City of Delhi, to discover palaces and tombs – all lost in time and overgrown with brambles and trees. Here we’ll learn to differentiate between Lodhi and Tughlaq architectural forms as we discover an ancient city that straddles both eras. -

Dynamics in Migration of Ashokan Edicts in and Around Delhi Vis. Soft Power Use by Muslim Rulers in Heritage Politics

International Conference on Heritage as Soft Power Dynamics in migration of Ashokan edicts in and around Delhi vis. soft power use by Muslim rulers in heritage politics Chander Sen President and Baudhcharya, Pachek Buddha Vihar Badarpur, Delhi-110044 [email protected] Bijay Beer Singh Ven. Sumedh Thero Sumedh Bhoomi Buddha Vihar, Dr. Ambedkar Park, Jhansipura, Lalitpur-284403 India Delhi being Heritage city meagerly emphasized about Buddhist studies and Buddhism. Keeping our ongoing interest in 20th century opens such doors and force us to study such Ancient sites. The first in-situ rock edict was discovered in Delhi in 1966, and establishes the city's ancient historical link with the Ashokan era (273–236 BC). Delhi's stone pillar edicts were transported from their original sites in Meerut and Ambala during the reign of Firuz Shah Tughlaq (1309–1388 AD). They were erected in Feruzabad, the fourth medieval city of Delhi, established by Feroz Shah Tughlaq. These Ashokan edicts in Delhi and around are a series of edicts on the teachings of Buddha created by Ashoka, the Mauryan Emperor who ruled in the Indian subcontinent during the 3rd century BC. The Edicts of Ashoka were either carved on in-situ rocks or engraved on pillars erected throughout the empire; examples of both are found in Delhi. The in-situ Bahapur rock edict was discovered in Delhi in an engraved form on a small patch of rock exposure in Srinivaspuri, one kilometer north of Kalkaji temple, close to Bahapur village in South Delhi. The edict categorized as a "Minor edict" written in Brahmi script was a first person message of Ashoka, which exhorts people to follow the Buddhist way of life.