Mythology in Shakespeare's Classical Plays

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sophocles, Ajax, Lines 1-171

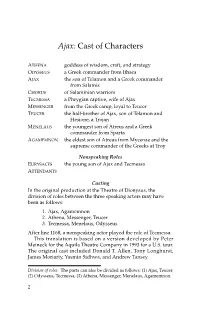

SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 2 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax: Cast of Characters ATHENA goddess of wisdom, craft, and strategy ODYSSEUS a Greek commander from Ithaca AJAX the son of Telamon and a Greek commander from Salamis CHORUS of Salaminian warriors TECMESSA a Phrygian captive, wife of Ajax MESSENGER from the Greek camp, loyal to Teucer TEUCER the half-brother of Ajax, son of Telamon and Hesione, a Trojan MENELAUS the youngest son of Atreus and a Greek commander from Sparta AGAMEMNON the eldest son of Atreus from Mycenae and the supreme commander of the Greeks at Troy Nonspeaking Roles EURYSACES the young son of Ajax and Tecmessa ATTENDANTS Casting In the original production at the Theatre of Dionysus, the division of roles between the three speaking actors may have been as follows: 1. Ajax, Agamemnon 2. Athena, Messenger, Teucer 3. Tecmessa, Menelaus, Odysseus After line 1168, a nonspeaking actor played the role of Tecmessa. This translation is based on a version developed by Peter Meineck for the Aquila Theatre Company in 1993 for a U.S. tour. The original cast included Donald T. Allen, Tony Longhurst, James Moriarty, Yasmin Sidhwa, and Andrew Tansey. Division of roles: The parts can also be divided as follows: (1) Ajax, Teucer; (2) Odysseus, Tecmessa; (3) Athena, Messenger, Menelaus, Agamemnon. 2 SophoclesFourTrag-00Bk Page 3 Thursday, July 26, 2007 3:56 PM Ajax SCENE: Night. The Greek camp at Troy. It is the ninth year of the Trojan War, after the death of Achilles. Odysseus is following tracks that lead him outside the tent of Ajax. -

The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen

Breakthrough and Concealment: The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 Howard Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Breakthrough and Concealment: The Formulaic Dynamics of Character Behavior in Lucan Howard Chen This dissertation analyzes the three main protagonists of Lucan’s Bellum Civile through their attempts to utilize, resist, or match a pattern of action which I call the “formula.” Most evident in Caesar, the formula is a cycle of alternating states of energy that allows him to gain a decisive edge over his opponents by granting him the ability of perpetual regeneration. However, a similar dynamic is also found in rivers, which thus prove to be formidable adversaries of Caesar in their own right. Although neither Pompey nor Cato is able to draw on the Caesarian formula successfully, Lucan eventually associates them with the river-derived variant, thus granting them a measure of resistance (if only in the non-physical realm). By tracing the development of the formula throughout the epic, the dissertation provides a deeper understanding of the importance of natural forces in Lucan’s poem as well as the presence of an underlying drive that unites its fractured world. Table of Contents Acknowledgments ............................................................................................................ vi Introduction ...................................................................................................................... -

Gillian Bevan Is an Actor Who Has Played a Wide Variety of Roles in West End and Regional Theatre

Gillian Bevan is an actor who has played a wide variety of roles in West End and regional theatre. Among these roles, she was Dorothy in the Royal Shakespeare Company revival of The Wizard of Oz, Mrs Wilkinson, the dance teacher, in the West End production of Billy Elliot, and Mrs Lovett in the West Yorkshire Playhouse production of Stephen Sondheim’s Sweeney Todd, the Demon Barber of Fleet Street. Gillian has regularly played roles in other Sondheim productions, including Follies, Merrily We Roll Along and Road Show, and she sang at the 80th birthday tribute concert of Company for Stephen Sondheim (Donmar Warehouse). Gillian spent three years with Alan Ayckbourn’s theatre-in-the-round in Scarborough, and her Shakespearian roles include Polonius (Polonia) in the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre production of Hamlet (Autumn, 2014) with Maxine Peake in the title role. Gillian’s many television credits have included Teachers (Channel 4) in which she played Clare Hunter, the Headmistress, and Holby City (BBC1) in which she gave an acclaimed performance as Gina Hope, a sufferer from Motor Neurone Disease, who ends her own life in an assisted suicide clinic. During the early part of 2014, Gillian completed filming London Road, directed by Rufus Norris, the new Artistic Director of the National Theatre. In the summer of 2014 Gillian played the role of Hera, the Queen of the Gods, in The Last Days of Troy by the poet and playwright Simon Armitage. The play, a re-working of The Iliad, had its world premiere at the Manchester Royal Exchange Theatre and then transferred to Shakespeare’s Globe Theatre, London. -

Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman D'alexandre

Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman d’Alexandre Paul Henri Rogers A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Romance Languages (French) Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: Dr. Edward D. Montgomery Dr. Frank A. Domínguez Dr. Edward D. Kennedy Dr. Hassan Melehy Dr. Monica P. Rector © 2008 Paul Henri Rogers ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Paul Henri Rogers Myth, the Marvelous, the Exotic, and the Hero in the Roman d’Alexandre Under the direction of Dr. Edward D. Montgomery In the Roman d’Alexandre , Alexandre de Paris generates new myth by depicting Alexander the Great as willfully seeking to inscribe himself and his deeds within the extant mythical tradition, and as deliberately rivaling the divine authority. The contemporary literary tradition based on Quintus Curtius’s Gesta Alexandri Magni of which Alexandre de Paris may have been aware eliminates many of the marvelous episodes of the king’s life but focuses instead on Alexander’s conquests and drive to compete with the gods’ accomplishments. The depiction of his premature death within this work and the Roman raises the question of whether or not an individual can actively seek deification. Heroic figures are at the origin of divinity and myth, and the Roman d’Alexandre portrays Alexander as an essentially very human character who is nevertheless dispossessed of the powerful attributes normally associated with heroic protagonists. -

Filostrato: an Unintentional Comedy?

Heliotropia 15 (2018) http://www.heliotropia.org Filostrato: an Unintentional Comedy? he storyline of Filostrato is easy to sum up: Troiolo, who is initially presented as a Hippolytus-type character, falls in love with Criseida. T Thanks to the mediation of Pandaro, mezzano d’amore, Troiolo and Criseida can very soon meet and enjoy each other’s love. Criseida is then unfortunately sent to the Greek camp, following an exchange of prisoners between the fighting opponents. Here she once again very quickly falls in love, this time with the Achaean warrior Diomedes. After days of emotional turmoil, Troiolo accidentally finds out about the affair: Diomedes is wearing a piece of jewellery that he had previously given to his lover as a gift.1 The young man finally dies on the battlefield in a rather abrupt fashion: “avendone già morti più di mille / miseramente un dì l’uccise Achille” [And one day, after a long stalemate, when he already killed more than a thou- sand, Achilles slew him miserably] (8.27.7–8). This very minimal plot is told in about 700 ottave (roughly the equivalent of a cantica in Dante’s Comme- dia), in which dialogues, monologues, and laments play a major role. In fact, they tend to comment on the plot, rather than feed it. I would insert the use of love letters within Filostrato under this pragmatic rationale: the necessity to diversify and liven up a plot which we can safely call flimsy. We could read the insertion of Cino da Pistoia’s “La dolce vista e ’l bel sguardo soave” (5.62–66) under the same lens: a sort of diegetic sublet that incorporates the words of someone else, in this case in the form of a poetic homage.2 Italian critics have insisted on the elegiac nature of Filostrato, while at the same time hinting at its ambiguous character, mainly in terms of not 1 “Un fermaglio / d’oro, lì posto per fibbiaglio” [a brooch of gold, set there perchance as clasp] (8.9). -

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G

Virgil, Aeneid 11 (Pallas & Camilla) 1–224, 498–521, 532–96, 648–89, 725–835 G Latin text, study aids with vocabulary, and commentary ILDENHARD INGO GILDENHARD AND JOHN HENDERSON A dead boy (Pallas) and the death of a girl (Camilla) loom over the opening and the closing part of the eleventh book of the Aeneid. Following the savage slaughter in Aeneid 10, the AND book opens in a mournful mood as the warring parti es revisit yesterday’s killing fi elds to att end to their dead. One casualty in parti cular commands att enti on: Aeneas’ protégé H Pallas, killed and despoiled by Turnus in the previous book. His death plunges his father ENDERSON Evander and his surrogate father Aeneas into heart-rending despair – and helps set up the foundati onal act of sacrifi cial brutality that caps the poem, when Aeneas seeks to avenge Pallas by slaying Turnus in wrathful fury. Turnus’ departure from the living is prefi gured by that of his ally Camilla, a maiden schooled in the marti al arts, who sets the mold for warrior princesses such as Xena and Wonder Woman. In the fi nal third of Aeneid 11, she wreaks havoc not just on the batt lefi eld but on gender stereotypes and the conventi ons of the epic genre, before she too succumbs to a premature death. In the porti ons of the book selected for discussion here, Virgil off ers some of his most emoti ve (and disturbing) meditati ons on the tragic nature of human existence – but also knows how to lighten the mood with a bit of drag. -

Study Questions Troilus and Cressida D R a F T

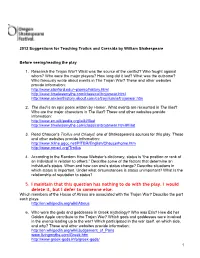

2012 Suggestions for Teaching Troilus and Cressida by William Shakespeare Before seeing/reading the play 1. Research the Trojan War? What was the source of the conflict? Who fought against whom? Who were the major players? How long did it last? What was the outcome? Who famously wrote about events in The Trojan War? These and other websites provide information: http://www.stanford.edu/~plomio/history.html http://www.timelessmyths.com/classical/trojanwar.html http://www.ancienthistory.about.com/cs/troyilium/a/trojanwar.htm 2. The Iliad is an epic poem written by Homer. What events are recounted in The Iliad? Who are the major characters in The Iliad? These and other websites provide information: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iliad http://www.timelessmyths.com/classical/trojanwar.html#Iliad 3. Read Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyd, one of Shakespeare's sources for this play. These and other websites provide information: http://www.tkline.pgcc.net/PITBR/English/Chaucerhome.htm http://www.omacl.org/Troilus 4. According to the Random House Webster’s dictionary, status is “the position or rank of an individual in relation to others.” Describe some of the factors that determine an individual’s status. When and how can one’s status change? Describe situations in which status is important. Under what circumstances is status unimportant? What is the relationship of reputation to status? 5. I maintain that this question has nothing to do with the play. I would delete it, but I defer to someone else. Which members of the House of Atreus are associated with the Trojan War? Describe the part each plays. -

Homer – the Iliad

HOMER – THE ILIAD Homer is the author of both The Iliad and The Odyssey. He lived in Ionia – which is now modern day Turkey – between the years of 900-700 BC. Both of the above epics provided the framework for Greek education and thought. Homer was a blind bard, one who is a professional story teller, an oral historian. Epos or epic means story. An epic is a particular type of story; it involves one with a hero in the midst of a battle. The subject of the poem is the Trojan War which happened approximately in 1200 BC. This was 400 years before the poem was told by Homer. This story would have been read aloud by Homer and other bards that came after him. It was passed down generation to generation by memory. One can only imagine how valuable memory was during that time period – there were no hard drives or memory sticks. On a tangential note, one could see how this poem influenced a culture; to be educated was to memorize a particular set of poems or stories which could be cross-referenced with other people’s memory of those particular stories. The information would be public and not private. The Iliad is one of the greatest stories ever told – a war between two peoples; the Greeks from the West and the Trojans from the East. The purpose of this story is to praise Achilles. The two worlds are brought into focus; the world of the divine order and the human order. The hero of the story is to bring greater order and harmony between these two orders. -

Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean Culture

ANTONIJE SHKOKLJEV SLAVE NIKOLOVSKI - KATIN PREHISTORY CENTRAL BALKANS CRADLE OF AEGEAN CULTURE Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture By Antonije Shkokljev Slave Nikolovski – Katin Translated from Macedonian to English and edited By Risto Stefov Prehistory - Central Balkans Cradle of Aegean culture Published by: Risto Stefov Publications [email protected] Toronto, Canada All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without written consent from the author, except for the inclusion of brief and documented quotations in a review. Copyright 2013 by Antonije Shkokljev, Slave Nikolovski – Katin & Risto Stefov e-book edition 2 Index Index........................................................................................................3 COMMON HISTORY AND FUTURE ..................................................5 I - GEOGRAPHICAL CONFIGURATION OF THE BALKANS.........8 II - ARCHAEOLOGICAL DISCOVERIES .........................................10 III - EPISTEMOLOGY OF THE PANNONIAN ONOMASTICS.......11 IV - DEVELOPMENT OF PALEOGRAPHY IN THE BALKANS....33 V – THRACE ........................................................................................37 VI – PREHISTORIC MACEDONIA....................................................41 VII - THESSALY - PREHISTORIC AEOLIA.....................................62 VIII – EPIRUS – PELASGIAN TESPROTIA......................................69 -

"Theater and Empire: a History of Assumptions in the English-Speaking Atlantic World, 1700-1860"

"THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" BY ©2008 Douglas S. Harvey Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________________ Chairperson Committee Members* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Defended: April 7, 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Douglas S. Harvey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" Committee ____________________________________ Chairperson ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Approved: April 7, 2008 ii Abstract It was no coincidence that commercial theater, a market society, the British middle class, and the “first” British Empire arose more or less simultaneously. In the seventeenth century, the new market economic paradigm became increasingly dominant, replacing the old feudal economy. Theater functioned to “explain” this arrangement to the general populace and gradually it became part of what I call a “culture of empire” – a culture built up around the search for resources and markets that characterized imperial expansion. It also rationalized the depredations the Empire brought to those whose resources and labor were coveted by expansionists. This process intensified with the independence of the thirteen North American colonies, and theater began representing Native Americans and African American populations in ways that rationalized the dominant society’s behavior toward them. By utilizing an interdisciplinary approach, this research attempts to advance a more nuanced and realistic narrative of empire in the early modern and early republic periods. -

Shakespeare, Aristotle, And

Colloquium on Violence & Religion Conference 2003 “Passions in Economy, Politics, and the Media. In Discussion with Christian Theology” University of Innsbruck, Austria (3.2 Literature) 14:00-15:30, Friday, June 20, 2003 Shakespeare, The ‘Prophet of Modern Advertising’, Aristotle, the ‘Strange Fellow’, and Ben Jonson and in Mimetic Rivalry the ‘Poets’ War’ Christopher S. Morrissey Department of Humanities 8888 University Drive Simon Fraser University Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A 1S6 PGP email: Key ID 0x6DD0285F Background: Achilles asks Ulysses at Troilus and Cressida 3.3.95 what he is reading. Ulysses reports what “a strange fellow”, an unnamed author, teaches him through the book, which he does not name (96-102). Achilles retorts emphatically that what Ulysses reports is quite commonplace and “not strange at all” (103-112). Many modern commentators have not hesitated to take Achilles’ side on the issue. They regard what is voiced (e.g. “beauty … commends itself to others’ eyes”: 104-106) as commonplace, finding the substance of Ulysses’ report (96-102) and Achilles’ paraphrase of it (103-112) in a variety of ancient and Renaissance sources. In a previous play, however, Shakespeare had a copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses brought onstage as a plot device (Titus Andronicus 4.1.42). Perhaps the same kind of self-conscious literary event is occurring in Troilus and Cressida, for Ulysses goes on to answer Achilles’ protest. He argues that the commonplaces (with which both Achilles and the modern commentators profess familiarity) are treated by the unnamed author in a decidedly different fashion (113-127). William R. Elton has suggested that the unnamed author is Aristotle and that the book to which the passage alludes is the Nicomachean Ethics (1129b30-3; cf. -

Pausanias' Description of Greece

BONN'S CLASSICAL LIBRARY. PAUSANIAS' DESCRIPTION OF GREECE. PAUSANIAS' TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH \VITTI NOTES AXD IXDEX BY ARTHUR RICHARD SHILLETO, M.A., Soiiii'tinie Scholar of Trinity L'olltge, Cambridge. VOLUME IT. " ni <le Fnusnnias cst un homme (jui ne mnnquo ni de bon sens inoins a st-s tlioux." hnniie t'oi. inais i}iii rn>it ou au voudrait croire ( 'HAMTAiiNT. : ftEOROE BELL AND SONS. YOUK STIIKKT. COVKNT (iAKDKX. 188t). CHISWICK PRESS \ C. WHITTINGHAM AND CO., TOOKS COURT, CHANCEKV LANE. fA LC >. iV \Q V.2- CONTEXTS. PAGE Book VII. ACHAIA 1 VIII. ARCADIA .61 IX. BtEOTIA 151 -'19 X. PHOCIS . ERRATA. " " " Volume I. Page 8, line 37, for Atte read Attes." As vii. 17. 2<i. (Catullus' Aft is.) ' " Page 150, line '22, for Auxesias" read Anxesia." A.-> ii. 32. " " Page 165, lines 12, 17, 24, for Philhammon read " Philanimon.'' " " '' Page 191, line 4, for Tamagra read Tanagra." " " Pa ire 215, linu 35, for Ye now enter" read Enter ye now." ' " li I'aijf -J27, line 5, for the Little Iliad read The Little Iliad.'- " " " Page ^S9, line 18, for the Babylonians read Babylon.'' " 7 ' Volume II. Page 61, last line, for earth' read Earth." " Page 1)5, line 9, tor "Can-lira'" read Camirus." ' ; " " v 1'age 1 69, line 1 , for and read for. line 2, for "other kinds of flutes "read "other thites.'' ;< " " Page 201, line 9. for Lacenian read Laeonian." " " " line 10, for Chilon read Cliilo." As iii. 1H. Pago 264, " " ' Page 2G8, Note, for I iad read Iliad." PAUSANIAS. BOOK VII. ACIIAIA.