Filostrato: an Unintentional Comedy?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

Boccaccio on Readers and Reading

Heliotropia 1.1 (2003) http://www.heliotropia.org Boccaccio on Readers and Reading occaccio’s role as a serious theorist of reading has not been a partic- ularly central concern of critics. This is surprising, given the highly B sophisticated commentary on reception provided by the two autho- rial self-defenses in the Decameron along with the evidence furnished by the monumental if unfinished project of his Dante commentary, the Espo- sizioni. And yet there are some very interesting statements tucked into his work, from his earliest days as a writer right to his final output, about how to read, how not to read, and what can be done to help readers. That Boccaccio was aware of the way genre affected the way people read texts is evident from an apparently casual remark in the Decameron. Having declared that his audience is to be women in love, he then announ- ces the contents of his book: intendo di raccontare cento novelle, o favole o parabole o istorie che dire le vogliamo. (Decameron, Proemio 13) The inference is that these are precisely the kinds of discourse appropriate for Boccaccio’s intended readership, lovelorn ladies. Attempts to interpret this coy list as a typology of the kinds of narration in the Decameron have been rather half-hearted, especially in commented editions. Luigi Russo (1938), for instance, makes no mention of the issue at all, and the same goes for Bruno Maier (1967) and Attilio Momigliano (1968). Maria Segre Consigli (1966), on the other hand, limits herself to suggesting that the three last terms are merely synonyms used by the author to provide a working definition of the then-unfamiliar term ‘novella’. -

Locating Boccaccio in 2013

Locating Boccaccio in 2013 Locating Boccaccio in 2013 11 July to 20 December 2013 Mon 12.00 – 5.00 Tue – Sat 10.00 – 5.00 Sun 12.00 – 5.00 The John Rylands Library The University of Manchester 150 Deansgate, Manchester, M3 3EH Designed by Epigram 0161 237 9660 1 2 Contents Locating Boccaccio in 2013 2 The Life of Giovanni Boccaccio (1313-1375) 3 Tales through Time 4 Boccaccio and Women 6 Boccaccio as Mediator 8 Transmissions and Transformations 10 Innovations in Print 12 Censorship and Erotica 14 Aesthetics of the Historic Book 16 Boccaccio in Manchester 18 Boccaccio and the Artists’ Book 20 Further Reading and Resources 28 Acknowledgements 29 1 Locating Boccaccio Te Life of Giovanni in 2013 Boccaccio (1313-1375) 2013 is the 700th anniversary of Boccaccio’s twenty-first century? His status as one of the Giovanni Boccaccio was born in 1313, either Author portrait, birth, and this occasion offers us the tre corone (three crowns) of Italian medieval in Florence or nearby Certaldo, the son of Decameron (Venice: 1546), opportunity not only to commemorate this literature, alongside Dante and Petrarch is a merchant who worked for the famous fol. *3v great author and his works, but also to reflect unchallenged, yet he is often perceived as Bardi company. In 1327 the young Boccaccio upon his legacy and meanings today. The the lesser figure of the three. Rather than moved to Naples to join his father who exhibition forms part of a series of events simply defining Boccaccio in automatic was posted there. As a trainee merchant around the world celebrating Boccaccio in relation to the other great men in his life, Boccaccio learnt the basic skills of arithmetic 2013 and is accompanied by an international then, we seek to re-present him as a central and accounting before commencing training conference held at the historic Manchester figure in the classical revival, and innovator as a canon lawyer. -

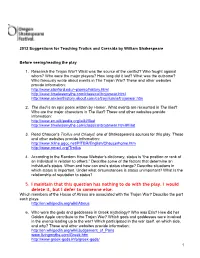

Study Questions Troilus and Cressida D R a F T

2012 Suggestions for Teaching Troilus and Cressida by William Shakespeare Before seeing/reading the play 1. Research the Trojan War? What was the source of the conflict? Who fought against whom? Who were the major players? How long did it last? What was the outcome? Who famously wrote about events in The Trojan War? These and other websites provide information: http://www.stanford.edu/~plomio/history.html http://www.timelessmyths.com/classical/trojanwar.html http://www.ancienthistory.about.com/cs/troyilium/a/trojanwar.htm 2. The Iliad is an epic poem written by Homer. What events are recounted in The Iliad? Who are the major characters in The Iliad? These and other websites provide information: http://www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Iliad http://www.timelessmyths.com/classical/trojanwar.html#Iliad 3. Read Chaucer’s Troilus and Criseyd, one of Shakespeare's sources for this play. These and other websites provide information: http://www.tkline.pgcc.net/PITBR/English/Chaucerhome.htm http://www.omacl.org/Troilus 4. According to the Random House Webster’s dictionary, status is “the position or rank of an individual in relation to others.” Describe some of the factors that determine an individual’s status. When and how can one’s status change? Describe situations in which status is important. Under what circumstances is status unimportant? What is the relationship of reputation to status? 5. I maintain that this question has nothing to do with the play. I would delete it, but I defer to someone else. Which members of the House of Atreus are associated with the Trojan War? Describe the part each plays. -

Shakespeare, Aristotle, And

Colloquium on Violence & Religion Conference 2003 “Passions in Economy, Politics, and the Media. In Discussion with Christian Theology” University of Innsbruck, Austria (3.2 Literature) 14:00-15:30, Friday, June 20, 2003 Shakespeare, The ‘Prophet of Modern Advertising’, Aristotle, the ‘Strange Fellow’, and Ben Jonson and in Mimetic Rivalry the ‘Poets’ War’ Christopher S. Morrissey Department of Humanities 8888 University Drive Simon Fraser University Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A 1S6 PGP email: Key ID 0x6DD0285F Background: Achilles asks Ulysses at Troilus and Cressida 3.3.95 what he is reading. Ulysses reports what “a strange fellow”, an unnamed author, teaches him through the book, which he does not name (96-102). Achilles retorts emphatically that what Ulysses reports is quite commonplace and “not strange at all” (103-112). Many modern commentators have not hesitated to take Achilles’ side on the issue. They regard what is voiced (e.g. “beauty … commends itself to others’ eyes”: 104-106) as commonplace, finding the substance of Ulysses’ report (96-102) and Achilles’ paraphrase of it (103-112) in a variety of ancient and Renaissance sources. In a previous play, however, Shakespeare had a copy of Ovid’s Metamorphoses brought onstage as a plot device (Titus Andronicus 4.1.42). Perhaps the same kind of self-conscious literary event is occurring in Troilus and Cressida, for Ulysses goes on to answer Achilles’ protest. He argues that the commonplaces (with which both Achilles and the modern commentators profess familiarity) are treated by the unnamed author in a decidedly different fashion (113-127). William R. Elton has suggested that the unnamed author is Aristotle and that the book to which the passage alludes is the Nicomachean Ethics (1129b30-3; cf. -

Shakespeare's Troilus and Cressida: a Commentary

University of Alberta Shakespeare's 'Itoüus and Cressida: A Commentary Lise Maren Signe Mills O A thesis subrnitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial Mllment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Department of Politicai Science Edmonton, Alberta Spring 2000 National tibrary Bibiii ue nationale 1+i OfCamda du Cana% A uisitions and Acquisitions et B%graphii Seivicas seMces bubliographiques 385 W- Süwt 395. lue WellGngtm OttawaON K1AON4 OltawaON K1AW Canada CMada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une iicence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lbrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distniute or seil reproduire, prêter, distriilmer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de niicrofiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author rehownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thése ni des exbraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de de-ci ne doivent êeimprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Troilus and Cressida is aot a play for the sentimental. Those who yeam for a seductive taie of brave waniors heroicaliy defendhg the honour of fair maidens would be better suited reading sornething hmHarlequin Romance. This thesis explores how, using the ancient story of the Trojan War as his foudation, Shakespeare strips love and glory--the two favorite motivations of men and women in popuiar romances-of their usual reverence. -

North American Boccaccio Bibliography for 1991 (Through November, 1991) Compiled by Christopher Kleinhenz, University of Wisconsin-Madison

Heliotropia 1.1 (2003) http://www.heliotropia.org North American Boccaccio Bibliography for 1991 (through November, 1991) Compiled by Christopher Kleinhenz, University of Wisconsin-Madison Books: Editions and Translations Boccaccio, Giovanni, Diana’s Hunt: Caccia di Diana. Boccaccio’s First Fiction, edited and translated by Anthony K. Cassell and Victoria Kirk- ham. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991. Pp. xvi + 255. ———, Ninfale fiesolano, a cura di Pier Massimo Forni. GUM, n.s., 196. Milano: Mursia, 1991. Pp. 208. Books: Critical Studies Doob, Penelope Reed, The Idea of the Labyrinth from Classical Antiq- uity through the Middle Ages. Ithaca, New York, and London: Cornell University Press, 1990. Pp. xviii + 355. [Contains sections on Boccac- cio’s Corbaccio and De Genealogia Deorum Gentilium.] Fleming, John V., Classical Imitation and Interpretation in Chaucer’s “Troilus”. Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1990. Pp. xviii + 276. Gilbert, Creighton E., Poets Seeing Artists’ Work: Instances in the Italian Renaissance. Firenze, Leo S. Olschki, 1991. Pp. 293. [Contains a long section on “Boccaccio’s Admirations,” including “Boccaccio’s De- votion to Artists and Art”; “The Fresco by Giotto in Milan”; “Boccaccio Looking at Actual Frescoes”; and “On Castagno’s Nine Famous Men and Women.”] Gittes, Katharine S., Framing the “Canterbury Tales”: Chaucer and the Medieval Frame Narrative Tradition. Greenwood, CT: Greenwood Press, 1991. Pp. 176. Hanly, Michael G., Boccaccio, Beauvau, Chaucer: “Troilus and Cri- seyde” (Four Perspectives on Influence). Norman: Pilgrim Books, 1990. McGregor, James H., The Image of Antiquity in Boccaccio’s “Filostrato,” “Filocolo,” and “Teseida.” “Studies in Italian Culture: Lit- erature and History,” I. -

The Amazon Myth in Western Literature. Bruce Robert Magee Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1996 The Amazon Myth in Western Literature. Bruce Robert Magee Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Magee, Bruce Robert, "The Amazon Myth in Western Literature." (1996). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6262. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6262 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the tmct directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter 6ce, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Chaucer's Troilus and Shakespeare's Troilus

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Eastern Illinois University Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1989 Chaucer's Troilus and Shakespeare's Troilus: A Comparison of Their eclinesD Laura Devon Flesor Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Flesor, Laura Devon, "Chaucer's Troilus and Shakespeare's Troilus: A Comparison of Their eD clines" (1989). Masters Theses. 2408. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2408 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. · Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion -

The Knight's Tale and the Teseide

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1946 The Knight's Tale and the Teseide Mary Felicita De Mato Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation De Mato, Mary Felicita, "The Knight's Tale and the Teseide" (1946). Master's Theses. 134. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/134 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1946 Mary Felicita De Mato THE KNIGHT'S TALE AliD THE TESEIDE A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Department of English Loyola University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of .Arts by Sister Mary Felicite. De :WiRtO, O.S •.M. November 1946 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER PAGE I. INTRODUCTI Oll • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 1 Historical and Literary Background • • • 1 The Poet•s Life • • • • • • • • • • • • 5 His Character • • • • • • • • • • • • • 9 His Friends • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 12 His Learning • • • • • • • • • • • • • 15 Relation to his Times • • • • • • • • • 17 II. CHAUCER AND THE RENAISSANCE • • • • • • • 22 Ohaucer•s relations with the Italian Language • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • Chaucer and Dante • • • • • • • • • • • • Chaucer and Il Canzoniere • • • • • • • His use of Italian sources provided by Dante and Petrarch • • • • • • • • • • 42 His indebtedness to "Lollius" exclusive of the Knight's Tale • • • • • • • • • 47 III. VARIOUS ASPECTS OF THE ITALIAN POET'S LIFE. -

"The Double Sorwe of Troilus": Experimentation of the Chivalric

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Scripps Senior Theses Scripps Student Scholarship 2019 "The oubleD Sorwe of Troilus": Experimentation of the Chivalric and Tragic Genres in Chaucer and Shakespeare Rena Patel Scripps College Recommended Citation Patel, Rena, ""The oubD le Sorwe of Troilus": Experimentation of the Chivalric and Tragic Genres in Chaucer and Shakespeare" (2019). Scripps Senior Theses. 1281. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/scripps_theses/1281 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Scripps Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scripps Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE DOUBLE SORWE OF TROILUS”: EXPERIMENTATION OF THE CHIVALRIC AND TRAGIC GENRES IN CHAUCER AND SHAKESPEARE by RENA PATEL SUBMITTED TO SCRIPPS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF ARTS PROFESSOR TESSIE PRAKAS PROFESSOR ELLEN RENTZ DECEMBER 14, 2018 Table of Contents Introduction 4 “Litel myn tragedie”: Tragedy in Chaucer’s Chivalric Romance 6 “’Tis but the chance of war”: Chivalry Undermining Shakespeare’s Tragedy 11 “So thenk I n’am but ded, withoute more”: Tragedy of Chivalric Fidelity 15 “Will you walk in, my lord?”: Shakespeare’s Performative Sham of Love 24 “True as Troilus, False as Cressid”: The Endings of Troilus 32 Conclusion 35 Bibliography 37 2 Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to offer my deepest admiration and appreciation to Professor Tessie Prakas, without whom this thesis would have never seen the light of day. Her enthusiasm and guidance has been invaluable not just in regards to the writing process, but also in all aspects of my time at Scripps. -

Trojan Horse Or Troilus's Whore? Pandering Statecraft and Political Stagecraft in Troilus and Cressida

Digital Commons @ Assumption University Philosophy Department Faculty Works Philosophy Department 2013 Trojan Horse or Troilus's Whore? Pandering Statecraft and Political Stagecraft in Troilus and Cressida Nalin Ranasinghe Assumption College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.assumption.edu/philosophy-faculty Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Ranasinghe, Nalin. "Trojan Horse or Troilus's Whore? Pandering Statecraft and Political Stagecraft in Troilus and Cressida." Shakespeare and the Body Politic. Edited by Bernard J. Dobski and Dustin Gish. Lexington Books, 2013, pp. 139-150. This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy Department at Digital Commons @ Assumption University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Department Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Assumption University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Chapter Seven Trojan Horse or Troilus's Whore? Pandering Statecraft and Political Stagecraft in Troilus and Cressida N alin Ranasinghe Although Shakespeare's rancid play Troilus and Cressida is evidently not suited for all markets and tastes, it yet contains much dark wisdom to reward one willing to probe its sordid surface. This chapter will expose the workings of its hidden Prince-Ulysses-who silently performs deeds that undercut the exoteric meaning of his stately speech in praise of degree. By winging .'•. ;.· well-chosen words to be intercepted, overheard and misunderstood, as well as by staging spectacles that humble proud allies and poison insecure adver saries, Ulysses shows how well his creator had absorbed the teachings of Homer and Machiavelli on vanity and honor.