Download File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebook Download a Reference Grammar of Modern Italian

A REFERENCE GRAMMAR OF MODERN ITALIAN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Martin Maiden,Cecilia Robustelli | 512 pages | 01 Jun 2009 | Taylor & Francis Ltd | 9780340913390 | Italian | London, United Kingdom A Reference Grammar of Modern Italian PDF Book This Italian reference grammar provides a comprehensive, accessible and jargon-free guide to the forms and structures of Italian. This rule is not absolute, and some exceptions do exist. Parli inglese? Italian is an official language of Italy and San Marino and is spoken fluently by the majority of the countries' populations. The rediscovery of Dante's De vulgari eloquentia , as well as a renewed interest in linguistics in the 16th century, sparked a debate that raged throughout Italy concerning the criteria that should govern the establishment of a modern Italian literary and spoken language. Compared with most other Romance languages, Italian has many inconsistent outcomes, where the same underlying sound produces different results in different words, e. An instance of neuter gender also exists in pronouns of the third person singular. Italian immigrants to South America have also brought a presence of the language to that continent. This article contains IPA phonetic symbols. Retrieved 7 August Italian is widely taught in many schools around the world, but rarely as the first foreign language. In linguistic terms, the writing system is close to being a phonemic orthography. For a group composed of boys and girls, ragazzi is the plural, suggesting that -i is a general plural. Book is in Used-Good condition. Story of Language. A history of Western society. It formerly had official status in Albania , Malta , Monaco , Montenegro Kotor , Greece Ionian Islands and Dodecanese and is generally understood in Corsica due to its close relation with the Tuscan-influenced local language and Savoie. -

Saint Alexius

Saint Alexius SAINT OF THE DAY 17-07-2021 Saint Alexius of Rome (4th-5th centuries) has been over the centuries a source of inspiration for men of letters and artists. Over time, various hagiographic versions of his figure have emerged, united by a fundamental trait: his renunciation of everything in order to follow God, obtaining the hundredfold promised by Jesus. His life is known through three traditions, one Syriac, one Greek and one Latin. The Syriac version, dating back to the end of the 5th century, is the oldest. It tells of a rich young man originally from Constantinople, the “New Rome”, who secretly boarded a ship the night before his wedding and reached Syria. That young man then continued on his way to Edessa (in what is now southern Turkey), a city with a large Christian community that for centuries guarded the Mandylion, a cloth bearing the Face of Jesus and identified by several scholars with the Shroud of Turin. There he lived begging for alms and in the evening he distributed to the poor what he had collected during the day, keeping for himself only the bare minimum to survive. Prayer and penance filled his days and because of his asceticism, the people called him Mar Riscia, that is “man of God”. After 17 years spent in Edessa, feeling close to the moment of death, he revealed that he belonged to a noble Roman family and had renounced marriage to consecrate himself to God. According to this ancient hagiography his death occurred while the Syrian writer Rabbula was Bishop of Edessa (c. -

II EDIZIONE Bambini E Gli Adolescenti Come “Individui”

Con il patrocinio di La data ricorda il giorno in cui l' Assemblea Partecipano al Progetto In collaborazione con la Commizssione 7 Generale delle Nazioni Unite adottò, nel 1989, di Firenze la convenzione ONU sui diritti dell'infanzia e dell'adolescenza. In collaborazione con Con il contributo di La “Carta dei Diritti del Bambino” fu scritta già nel 1923 da Eglantyne Jebb, dama della Croce Rossa. Ancora oggi molti sono i bambini e gli adolescenti, anche in Italia, vittime di violenza, abusi, discriminazioni, che vivono situazioni di trascuratezza sociale – psicologica nonché scolastica e culturale. Tutti abbiamo il dovere di prendere coscienza dell'importanza di trattare i II EDIZIONE bambini e gli adolescenti come “individui”. Il tema Giornata Mondiale è particolarmente sentito dagli Artisti Fiesolani che operano affinché “l'Arte e la Cultura” possano dei Diritti dell'Infanzia mantenere il primato tra le attività umane. e dell'Adolescenza Artisti in esposizione: Fiamma Antoni Ciotti Irina Meniailova Mariangela Bartoloni Valerio Mirannalti Francesco Beccastrini Lorenzo Montagni Stefania Biagioni Susanna Pellegrini Istituto Comprensivo “Coverciano” Via Salvi Cristiani, 3 – 50135 Firenze Fernando Cardenas Scuola Primaria S.Maria a Coverciano Francesco Perna Barbara Cascini Puccio Pucci Alessandro Ciappi COMUNE DI GAMBASSI TERME ISTITUTO COMPRENSIVO STATALE Matteo Rimi E DI MONTAIONE “Ernesto BALDUCCI” Roberto Coccoloni Mariadonata Sirleo Andrea Sole Costa Roberto D’Angelo Sanja Spasic Laura Felici Paola Stazzoni Alessandro Goggioli Sara -

[email protected] [email protected] NUMERI UTILI / / UTILI NUMERI User Numbers User

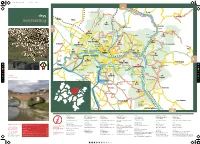

A3-Map-Pontassieve.pdf 1 03/12/19 19:24 ✟ CONVENTO ✟ PIEVE DI S. GIOVANNI MAGGIORE di Bilancino DI BOSCO AI FRATI Villore CAFAGGIOLO Borgo S. Lorenzo BOLOGNA Le Croci di Calenzano Vicchio Map S. Godenzo Pontassieve Agliana PRATO A1 Legri Vaglia CONVENTO Dicomano PISA DI MONTE SENARIO Frascole Rincine Pratolino Contea Calenzano Olmo Acone VILLA DEMIDOFF S. Brigida Cercina Londa A11 Colonnata Scopeti Capalle LA PETRAIA Caldine Sesto Fiorentino CASTELLO Monteloro Pomino Carmignano ✟ PIEVE DI S. BARTOLOMEO Campi Bisenzio AEROPORTO Fiesole Molin del Piano DI FIRENZE Careggi Stia S. Donnino Sieci Signa Pratovecchio Vinci Badia a Settimo FIRENZE Settignano Pontassieve Diacceto FI-PI-LI Castra Pelago Rosano RAVENNA Lastra a Signa Cerreto Guidi ✟ Villamagna Ponte a Cappiano Limite Scandicci Tosi Galluzzo Montemignaio Sovigliana Bagno a Ripoli S. Ellero C Capraia Ponte a Ema Fucecchio Mosciano Certosa Vallombrosa M Grassina S. Croce sull’Arno Rignano sull’Arno ✟ PIEVE Saltino Antella A PITIANA Poppi Y Ginestra Fiorentina S. Donato Empoli in Collina CM Tavarnuzze Chiesanuova Leccio MY Castelfranco di sotto Firenze e torrente Pesa S. Vincenzo a Torri CY Ponte a Elsa Impruneta Area Fiorentina Cerbaia A1 Reggello CMY FI-PI-LI S. Miniato ✟ S. Casciano in Val di Pesa FIRENZE-SIENA PIEVE DI CASCIA K S. Polo in Chianti Baccaiano Montopoli in Val d’Arno Il Ferrone Strada in Chianti Incisa Poppiano Montespertoli Mercatale in Val di Pesa Pian di Scò Cambiano Castelnuovo d’Elsa Cintoia Figline Passo dei Pecorai Palaia Dudda Greve in Chianti Loro Ciuffenna Gaville ✟ PIEVE DI Mura S. ROMOLO S. Giovanni Valdarno Tavarnelle in Val di Pesa AREZZO Terranuova Bracciolini Montaione ✟ Peccioli Certaldo S. -

Volume 35 E-Mail: [email protected] Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 Autumn 2015

The Harvard University Center for Italian Renaissance Studies VILLA I TATTI Via di Vincigliata 26, 50135 Florence, Italy Volume 35 E-mail: [email protected] Tel: +39 055 603 251 / Fax: +39 055 603 383 Autumn 2015 Letter from Florence It’s the end of June 2015, and Anna and I are preparing to leave Mensola, and Boccaccio and Petrarca, and Laura Battiferra I Tatti for the last time. It has been an intense and wonderful too. We are grateful to all of them for opening our eyes to five-year period at the Villa, with exceptional groups of the beauty of this valley, and enhancing the experience of our Fellows, Visiting Professors, and guests joining us from all walk with their words. corners of the world. And it has seemed a very quick period, too. The last year has gone in a flash. It seems only yesterday Our walk also offers us a chance to talk about what’s going on that we were harvesting our grapes, and already our vineyards in the day, the ups and downs, the ins and outs of la vita tattiana: are once more covered in luxuriant foliage while the olive who is leaving, and who is coming next to I Tatti, the lectures, groves are rich with the promise of new oil for the fettunta. conferences, and concerts in preparation, and the books that Anna and I love this little Mensola valley and never miss an have just appeared and those that are due out soon. But it’s opportunity to admire the beautiful, peaceful order in which also a marvelous opportunity to see how the restoration of the everything – vigne, oliveti, giardini e case – is kept by our staff. -

Using Italian

This page intentionally left blank Using Italian This is a guide to Italian usage for students who have already acquired the basics of the language and wish to extend their knowledge. Unlike conventional grammars, it gives special attention to those areas of vocabulary and grammar which cause most difficulty to English speakers. Careful consideration is given throughout to questions of style, register, and politeness which are essential to achieving an appropriate level of formality or informality in writing and speech. The book surveys the contemporary linguistic scene and gives ample space to the new varieties of Italian that are emerging in modern Italy. The influence of the dialects in shaping the development of Italian is also acknowledged. Clear, readable and easy to consult via its two indexes, this is an essential reference for learners seeking access to the finer nuances of the Italian language. j. j. kinder is Associate Professor of Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He has published widely on the Italian language spoken by migrants and their children. v. m. savini is tutor in Italian at the Department of European Languages and Studies, University of Western Australia. He works as both a tutor and a translator. Companion titles to Using Italian Using French (third edition) Using Italian Synonyms A guide to contemporary usage howard moss and vanna motta r. e. batc h e lor and m. h. of f ord (ISBN 0 521 47506 6 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 64177 2 hardback) (ISBN 0 521 47573 2 paperback) (ISBN 0 521 64593 X paperback) Using French Vocabulary Using Spanish jean h. -

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis

Petrarch and Boccaccio Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 61 Petrarch and Boccaccio The Unity of Knowledge in the Pre-modern World Edited by Igor Candido An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. The Open Access book is available at www.degruyter.com. ISBN 978-3-11-042514-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-041930-6 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-041958-0 ISSN 0178-7489 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 license. For more information, see http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2018 Igor Candido, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Typesetting: Konvertus, Haarlem Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck ♾ Printed on acid-free paper Printed in Germany www.degruyter.com Dedicated to Ronald Witt (1932–2017) Contents Acknowledgments IX Igor Candido Introduction 1 H. Wayne Storey The -

Holy Trinity Catholic Church December 15, 2019 Third Sunday Of

Holy Trinity Catholic Church A Stewardship Parish December 15, 2019 Third Sunday of Advent Pastor: Fr. Michel Dalton, OFM Capuchin Deacons: Steve Kula and Fernando Ona Masses: Saturday: 5 pm; Sunday: 7, 9 & 11 am; Weekdays: 5 pm Reconciliation (Confession): Saturday: 3:45 - 4:15 or by appointment Our vision: To be a welcoming parish committed to serving others. Our mission: To make Christ known to the world through Word, Sacrament, Prayer and Service HOLY TRINITY CHURCH CALENDAR FOR DECEMBER 2019 Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Mass 7, 9, 11 5:00 pm Mass 10:00 am 9:00 am 5:00 pm 5:00 pm Mass 3:45 pm Crafters Group Bible Study in Eucharistic Reconciliation 10:00 am in Makai House Makai House Service Religious Ed 5:00 pm Mass 5:00 pm Mass 5:00 pm Mass 6:00-7:30 pm Bible Study in 6:30 pm Choir 7:00 pm the PMR Charismatic 7:15 pm Prayer Group Neo Way Community 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Mass 7, 9, 11 5:00 pm Mass CHRISTMAS CHRISTMAS 5:00 pm 5:00 pm Mass 3:45 pm EVE DAY Eucharistic Reconciliation 6:00-7:30 pm Service Bible Study in 4:30 pm CHURCH 5:00 pm Mass the PMR Caroling OFFICE CLOSED 5:00 pm Mass 8:45 am 8:15pm Caroling Caroling 9:00 am Mass 9:00 pm Mass 10:45 am Caroling 11:00 am Mass CHRISTMAS MASS SCHEDULE Tue December 24 5:00 pm Mass Tue December 24 9:00 pm Mass Wed December 25 9:00 am Mass Wed December 25 11:00 am Mass Scripture Readings Readings for Sunday December 15, 2019 Third Sunday of Advent 1st Reading Is 35:1-6a 2nd Reading Jas 5:7-10 Gospel Mt 11:2-11 Holy Trinity Church Contact Information 5919 Kalanianaole Highway, Honolulu, HI 96821 Readings for Sunday December 22, 2019 E-Mail: [email protected] Fourth Sunday of Advent Website: holytrinitychurchhi.org Telephone (808) 396-0551 1st Reading Is 7:10-14 Emergency Telephone: (808) 772-2422 2nd Reading Rom 1:1-7 Please email [email protected] QR Code if you have questions on the Bulletin. -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto -

Boccaccio on Readers and Reading

Heliotropia 1.1 (2003) http://www.heliotropia.org Boccaccio on Readers and Reading occaccio’s role as a serious theorist of reading has not been a partic- ularly central concern of critics. This is surprising, given the highly B sophisticated commentary on reception provided by the two autho- rial self-defenses in the Decameron along with the evidence furnished by the monumental if unfinished project of his Dante commentary, the Espo- sizioni. And yet there are some very interesting statements tucked into his work, from his earliest days as a writer right to his final output, about how to read, how not to read, and what can be done to help readers. That Boccaccio was aware of the way genre affected the way people read texts is evident from an apparently casual remark in the Decameron. Having declared that his audience is to be women in love, he then announ- ces the contents of his book: intendo di raccontare cento novelle, o favole o parabole o istorie che dire le vogliamo. (Decameron, Proemio 13) The inference is that these are precisely the kinds of discourse appropriate for Boccaccio’s intended readership, lovelorn ladies. Attempts to interpret this coy list as a typology of the kinds of narration in the Decameron have been rather half-hearted, especially in commented editions. Luigi Russo (1938), for instance, makes no mention of the issue at all, and the same goes for Bruno Maier (1967) and Attilio Momigliano (1968). Maria Segre Consigli (1966), on the other hand, limits herself to suggesting that the three last terms are merely synonyms used by the author to provide a working definition of the then-unfamiliar term ‘novella’. -

New Approaches Toward Recent Gay Chicano Authors and Their Audience

Selling a Feeling: New Approaches Toward Recent Gay Chicano Authors and Their Audience Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Douglas Paul William Bush, M.A. Graduate Program in Spanish and Portuguese The Ohio State University 2013 Dissertation Committee: Ignacio Corona, Advisor Frederick Luis Aldama Fernando Unzueta Copyright by Douglas Paul William Bush 2013 Abstract Gay Chicano authors have been criticized for not forming the same type of strong literary identity and community as their Chicana feminist counterparts, a counterpublic that has given voice not only to themselves as authors, but also to countless readers who see themselves reflected in their texts. One of the strengths of the Chicana feminist movement is that they have not only produced their own works, but have made sense of them as well, creating a female-to-female tradition that was previously lacking. Instead of merely reiterating that gay Chicano authors have not formed this community and common identity, this dissertation instead turns the conversation toward the reader. Specifically, I move from how authors make sense of their texts and form community, to how readers may make sense of texts, and finally, to how readers form community. I limit this conversation to three authors in particular—Alex Espinoza, Rigoberto González, and Manuel Muñoz— whom I label the second generation of gay Chicano writers. In González, I combine the cognitive study of empathy and sympathy to examine how he constructs affective planes that pull the reader into feeling for and with the characters that he draws. -

Filostrato: an Unintentional Comedy?

Heliotropia 15 (2018) http://www.heliotropia.org Filostrato: an Unintentional Comedy? he storyline of Filostrato is easy to sum up: Troiolo, who is initially presented as a Hippolytus-type character, falls in love with Criseida. T Thanks to the mediation of Pandaro, mezzano d’amore, Troiolo and Criseida can very soon meet and enjoy each other’s love. Criseida is then unfortunately sent to the Greek camp, following an exchange of prisoners between the fighting opponents. Here she once again very quickly falls in love, this time with the Achaean warrior Diomedes. After days of emotional turmoil, Troiolo accidentally finds out about the affair: Diomedes is wearing a piece of jewellery that he had previously given to his lover as a gift.1 The young man finally dies on the battlefield in a rather abrupt fashion: “avendone già morti più di mille / miseramente un dì l’uccise Achille” [And one day, after a long stalemate, when he already killed more than a thou- sand, Achilles slew him miserably] (8.27.7–8). This very minimal plot is told in about 700 ottave (roughly the equivalent of a cantica in Dante’s Comme- dia), in which dialogues, monologues, and laments play a major role. In fact, they tend to comment on the plot, rather than feed it. I would insert the use of love letters within Filostrato under this pragmatic rationale: the necessity to diversify and liven up a plot which we can safely call flimsy. We could read the insertion of Cino da Pistoia’s “La dolce vista e ’l bel sguardo soave” (5.62–66) under the same lens: a sort of diegetic sublet that incorporates the words of someone else, in this case in the form of a poetic homage.2 Italian critics have insisted on the elegiac nature of Filostrato, while at the same time hinting at its ambiguous character, mainly in terms of not 1 “Un fermaglio / d’oro, lì posto per fibbiaglio” [a brooch of gold, set there perchance as clasp] (8.9).