Literary Destinations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut

MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS No. CT-359-A (Samuel Clemens Carriage House) 351 Farmington Avenue WABS Hartford Hartford County- Connecticut WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA REDUCED COPIES OF THE MEASURED DRAWINGS PHOTOGRAPHS Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 m HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY MARK TWAIN CARRIAGE HOUSE HABS NO. CT-359-A Location: Rear of 351 Farmington Avenue, Hartford, Hartford County, Connecticut. USGS Hartford North Quadrangle, Universal Transverse Mercator Coordinates; 18.691050.4626060. Present Owner. Occupant. Use: Mark Twain Memorial, the former residence of Samuel Langhorne Clemens (better known as Mark Twain), now a house museum. The carriage house is a mixed-use structure and contains museum offices, conference space, a staff kitchen, a staff library, and storage space. Significance: Completed in 1874, the Mark Twain Carriage House is a multi-purpose barn with a coachman's apartment designed by architects Edward Tuckerman Potter and Alfred H, Thorp as a companion structure to the residence for noted American author and humorist Samuel Clemens and his family. Its massive size and its generous accommodations for the coachman mark this structure as an unusual carriage house among those intended for a single family's use. The building has the wide overhanging eaves and half-timbering typical of the Chalet style popular in the late 19th century for cottages, carriage houses, and gatehouses. The carriage house apartment was -

Jervis Langdon, Jr

Mark Twain Circular Newsletter of the Mark Twain Circle of America Volume 18 April 2004 Number 1 The Death of Jervis Langdon, Jr. Jervis Langdon, Jr. 1905-2004 Gretchen Sharlow, Director Center for MT Studies at Quarry Farm Shelley Fisher Fishkin Stanford University It is with deep appreciation and respect that the Elmira College community I was saddened to learn of the death of Jervis mourns the loss of Mark Twain’s grand- Langdon, Jr. on February 16, 2004, and wanted to nephew, Jervis Langdon, Jr., who died take this opportunity to remember him as a gra- February 16, 2004, at his home in Elmira, cious, generous and public-spirited man. I had the New York, at the age of 99. pleasure of meeting Jervis Langdon, Jr. and his With his 1982 gift of the beloved wonderful wife, Irene, three years ago in Elmira. I family home Quarry Farm to Elmira Col- was struck by the way he embraced the legacies lege, and his vision to nurture Twain both of his great grandfather, Jervis Langdon scholarship, Jervis Langdon, Jr. made a (Olivia Langdon Clemens' father, and Sam Clem- major impact on the world of Mark Twain ens' father-in-law), and of his grand-uncle Mark studies. The Elmira College Center for Twain, with wisdom and sensitivity. Mark Twain Studies was developed in In May, 1869, his great grandfather, Jervis 1983 with a mission to foster the study Langdon, purchased the East Hill property in El- Mark Twain, his life, his literature, and his mira that would become Quarry Farm, the home significant influence on American culture. -

Gentlemen of Genius (PDF Document)

“GENTLEMEN OF GENIUS” ITINERARY – AN ADVENTURE ALONG THE MISSOURI HIGHWAY 36 CORRIDOR FEATURING: MARK TWAIN, WALT DISNEY, JESSE JAMES, & THE PONY EXPRESS This itinerary can do east to west or west to east, and could start or end at any point. The trip below goes East to West) DAY 1 HANNIBAL, MO – MARK TWAIN Contact: Megan Rapp, Assistant Director & Group Sales Manager toll free – 1-TOM-AND-HUCK Hannibal Convention & Visitors Bureau 505 North Third Street Hannibal, MO 63401 [email protected] www.VisitHannibal.com The Hannibal Convention & Visitors Bureau can help you by planning a custom itinerary to fit your schedule, and we provide free itinerary booking! Call or email us to book the Hannibal itinerary below or to create your own unique HWY 36 adventure! 7:00 – 8:30 am - Breakfast at hotel 9:30 am - Tom Sawyer & Becky Thatcher greet group at Mark Twain Museum See one of the most famous literary couples act out their engagement in front of the Mark Twain Boyhood Home. 10:00 am - Explore the Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum properties on a fun self-guided tour. Begin tour of Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum Properties. This self-guided tour allows your group to explore the roots of Mark Twain’s genius. The tour includes 7 buildings, most notably the world famous Mark Twain Boyhood Home. It also includes two exciting, interactive museums whose collections include fifteen original Norman Rockwell paintings. Your group can also choose a docent-led tour for an additional charge. 11:30 am - Special Mark Twain Curator talk for group – can be arranged. -

Mark Twain - Wikipedia the Free Encyclopedia

Mark twain - wikipedia the free encyclopedia click here to download Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, – April 21, ), better known by his pen name Mark Twain, was an American writer, humorist, entrepreneur, publisher, and lecturer. Among his novels are The Adventures of Tom Sawyer () and its sequel, the Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (), the latter often Notable works: Adventures of Huckleberry Finn;. Samuel Langhorne Clemens (November 30, – April 21, ), more widely known as Mark Twain, was a well known American writer born in Florida, Missouri. He worked mainly for newspapers and as a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River before he became a writer. He married in , and raised his family in. Mark Twain (crater) · Mark Twain at the Territorial Enterprise · Mark Twain Birthplace State Historic Site · Mark Twain Boyhood Home & Museum · Mark Twain Casino · Mark Twain Cave · Mark Twain Historic District · Mark Twain House · Mark Twain Lake · Mark Twain Memorial Bridge · Mark Twain Memorial Bridge (). The Mysterious Stranger is a novel attempted by the American author Mark Twain. He worked on it intermittently from through Twain wrote multiple versions of the story; each involves a supernatural character called "Satan" or "No. 44". All the versions remained unfinished (with the debatable exception of the last. Pages in category "Novels by Mark Twain". The following 16 pages are in this category, out of 16 total. This list may not reflect recent changes (learn more). A. Adventures of Huckleberry Finn · The Adventures of Tom Sawyer · The American Claimant. C. A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur's Court. D. A Double Barrelled. Joan of Arc, Dick Cheney, Mark Twain is the seventh full-length album by Joan of Arc, released in It is their first for Polyvinyl Records. -

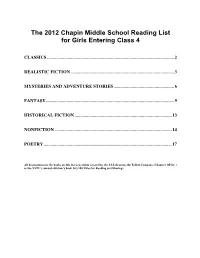

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4

The 2012 Chapin Middle School Reading List for Girls Entering Class 4 CLASSICS ............................................................................................................... 2 REALISTIC FICTION .......................................................................................... 3 MYSTERIES AND ADVENTURE STORIES ..................................................... 6 FANTASY ................................................................................................................ 9 HISTORICAL FICTION ..................................................................................... 13 NONFICTION ...................................................................................................... 14 POETRY ................................................................................................................ 17 All descriptions for the books on this list were either created by the LS Librarian, the Follett Company (Chapin’s OPAC ) or the NYPL’s annual children’s book list (100 Titles for Reading and Sharing). Classics Aiken, Joan. Wolves of Willoughby Chase. Two young girls are sent to live on an isolated country estate where they find themselves in the clutches of an evil governess. Alcott, Louisa May Little Women Follow the lives of four sisters in nineteenth-century New England. Baum, L. Frank. The Wizard Of Oz. An elegant and rich story about a girl, her friends, and a humbug wizard. Burnett, Frances Hodgson. The Secret Garden. A young orphan named Mary is sent to live at a creepy English estate -

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 158 WASHINGTON, MONDAY, APRIL 16, 2012 No. 54 House of Representatives The House met at 2 p.m. and was THE JOURNAL I look forward to these joint collabo- called to order by the Speaker pro tem- The SPEAKER pro tempore. The rations with the Savannah River Na- pore (Mr. HARRIS). Chair has examined the Journal of the tional Laboratory, and I am confident their success will be of great benefit to f last day’s proceedings and announces to the House his approval thereof. South Carolina and our Nation. In conclusion, God bless our troops, DESIGNATION OF THE SPEAKER Pursuant to clause 1, rule I, the Jour- and we will never forget September the PRO TEMPORE nal stands approved. 11th in the global war on terrorism. The SPEAKER pro tempore laid be- f Rest in peace, Medal of Honor recipi- fore the House the following commu- PLEDGE OF ALLEGIANCE ent Army Master Sergeant John F. nication from the Speaker: The SPEAKER pro tempore. Will the Baker, Jr., of Columbia, South Caro- WASHINGTON, DC, gentleman from Illinois (Mr. lina, and Rock Island, Illinois, for his April 16, 2012. KINZINGER) come forward and lead the heroic service in Vietnam, who was I hereby appoint the Honorable ANDY HAR- House in the Pledge of Allegiance. buried at Arlington National Cemetery RIS to act as Speaker pro tempore on this Mr. KINZINGER of Illinois led the today. -

MTC-Brochure.Pdf

You can find it all at Wines, Gifts, Candies, Semi- Driving Distances to Hannibal All Roads Lead to Hannibal The Mark Twain Cave Complex! Minneapolis/St. Paul Precious Stones & Entertainment Inside Missouri Des Moines, IA 220 462 miles Detroit, MI 556 Milwaukee Branson 280 35 359 miles Inside Missouri Dubuque, IA 244 Cape Girardeau 217 Branson .................. 280 Columbia 98 Indianapolis, IN 310 94 Cape Girardeau ..... 217 Independence 210 Lincoln, NE 334 Davenport 164 miles Chicago Columbia ................. 98 Jeerson City 106 Little Rock, AR 439 Des Moines 295 miles 220 miles Louisville, KY 372 O maha Independence ........ 210 Joplin 312 328 miles 29 61 Peoria Kansas City 210 Madison, WI 328 143 miles Jefferson City ......... 106 24 Lake of the Ozarks 150 Memphis, TN 386 65 Joplin ...................... 312 HAN N IBAL Springeld 244 Milwaukee, WI 359 72 Kansas City ........... 210 36 Springfield St. Charles 98 Minneapolis, MN 445 55 100 miles Open All Year! Topeka Lake of the Ozarks .... 150 Ste. Genevieve 165 Nashville, TN 423 263 70 Kansas City St. Louis Springfield ............. 244 St. Joseph 194 Nauvoo, IL 70 200 miles 100 miles No Steps 54 St. Charles ................ 98 St. Louis 117 New Orleans, LA 774 65 Oklahoma City, OK 526 Ste. Genevieve ....... 165 Springfield 44 St. Joseph .............. 194 Outside Missouri Omaha, NE 328 237 miles Branson 55 Atlanta, GA 670 Peoria, IL 143 280 miles St. Louis ................. 117 Tulsa Chicago, IL 303 Springeld, IL 100 423 miles Cincinnati, OH 424 Topeka, KS 263 Memphis Little Rock -

The Letters of Mark Twain, Complete by Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens)

The Letters Of Mark Twain, Complete By Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) 1 VOLUME I By Mark Twain MARK TWAIN'S LETTERS I. EARLY LETTERS, 1853. NEW YORK AND PHILADELPHIA We have no record of Mark Twain's earliest letters. Very likely they were soiled pencil notes, written to some school sweetheart --to "Becky Thatcher," perhaps--and tossed across at lucky moments, or otherwise, with happy or disastrous results. One of those smudgy, much-folded school notes of the Tom Sawyer period would be priceless to-day, and somewhere among forgotten keepsakes it may exist, but we shall not be likely to find it. No letter of his boyhood, no scrap of his earlier writing, has come to light except his penciled name, SAM CLEMENS, laboriously inscribed on the inside of a small worn purse that once held his meager, almost non-existent wealth. He became a printer's apprentice at twelve, but as he received no salary, the need of a purse could not have been urgent. He must have carried it pretty steadily, however, from its 2 appearance--as a kind of symbol of hope, maybe--a token of that Sellers-optimism which dominated his early life, and was never entirely subdued. No other writing of any kind has been preserved from Sam Clemens's boyhood, none from that period of his youth when he had served his apprenticeship and was a capable printer on his brother's paper, a contributor to it when occasion served. Letters and manuscripts of those days have vanished--even his contributions in printed form are unobtainable. -

Caves of Missouri

CAVES OF MISSOURI J HARLEN BRETZ Vol. XXXIX, Second Series E P LU M R I U BU N S U 1956 STATE OF MISSOURI Department of Business and Administration Division of GEOLOGICAL SURVEY AND WATER RESOURCES T. R. B, State Geologist Rolla, Missouri vii CONTENT Page Abstract 1 Introduction 1 Acknowledgments 5 Origin of Missouri's caves 6 Cave patterns 13 Solutional features 14 Phreatic solutional features 15 Vadose solutional features 17 Topographic relations of caves 23 Cave "formations" 28 Deposits made in air 30 Deposits made at air-water contact 34 Deposits made under water 36 Rate of growth of cave formations 37 Missouri caves with provision for visitors 39 Alley Spring and Cave 40 Big Spring and Cave 41 Bluff Dwellers' Cave 44 Bridal Cave 49 Cameron Cave 55 Cathedral Cave 62 Cave Spring Onyx Caverns 72 Cherokee Cave 74 Crystal Cave 81 Crystal Caverns 89 Doling City Park Cave 94 Fairy Cave 96 Fantastic Caverns 104 Fisher Cave 111 Hahatonka, caves in the vicinity of 123 River Cave 124 Counterfeiters' Cave 128 Robbers' Cave 128 Island Cave 130 Honey Branch Cave 133 Inca Cave 135 Jacob's Cave 139 Keener Cave 147 Mark Twain Cave 151 Marvel Cave 157 Meramec Caverns 166 Mount Shira Cave 185 Mushroom Cave 189 Old Spanish Cave 191 Onondaga Cave 197 Ozark Caverns 212 Ozark Wonder Cave 217 Pike's Peak Cave 222 Roaring River Spring and Cave 229 Round Spring Cavern 232 Sequiota Spring and Cave 248 viii Table of Contents Smittle Cave 250 Stark Caverns 256 Truitt's Cave 261 Wonder Cave 270 Undeveloped and wild caves of Missouri 275 Barry County 275 Ash Cave -

"Theater and Empire: a History of Assumptions in the English-Speaking Atlantic World, 1700-1860"

"THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" BY ©2008 Douglas S. Harvey Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________________ Chairperson Committee Members* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Defended: April 7, 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Douglas S. Harvey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" Committee ____________________________________ Chairperson ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Approved: April 7, 2008 ii Abstract It was no coincidence that commercial theater, a market society, the British middle class, and the “first” British Empire arose more or less simultaneously. In the seventeenth century, the new market economic paradigm became increasingly dominant, replacing the old feudal economy. Theater functioned to “explain” this arrangement to the general populace and gradually it became part of what I call a “culture of empire” – a culture built up around the search for resources and markets that characterized imperial expansion. It also rationalized the depredations the Empire brought to those whose resources and labor were coveted by expansionists. This process intensified with the independence of the thirteen North American colonies, and theater began representing Native Americans and African American populations in ways that rationalized the dominant society’s behavior toward them. By utilizing an interdisciplinary approach, this research attempts to advance a more nuanced and realistic narrative of empire in the early modern and early republic periods. -

Fall 2011.Indd

Elmira College Center for Mark Twain Studies The Trouble Begins at Eight Fall 2011 Lecture Series Wednesday, September 21st in the Barn at Quarry Farm 8 p.m. “...the quietest of all quiet places...” Barbara E. Snedecor Elmira College In a letter to John Brown, a physician friend from Edin- burgh, Scotland, Clemens wrote: I wish you were here, to spend the summer with us. We are perched on a hill-top that over- looks a little world of green valleys, shining rivers, sumptuous for- ests, & billowy uplands veiled in the haze of distance. We have no neighbors. It is the quietest of all quiet places, & we are hermits that eschew caves & live in the sun. (June 22, 1876) Join Barbara Snedecor as she recounts in words and pictures the familiar tale of courtship, marriage, and of summers spent at Quarry Farm -- the quietest of all quiet places. Doors open at 7:30. The Trouble Begins at Eight. Wednesday, September 28th in the Barn at Quarry Farm 8 p.m. Mark Twain’s Nature in Roughing It, Naturally Michael Pratt Elmira College For most of us, the author Mark Twain is indelibly linked with his classic books about two ju- venile delinquents, Huck Finn and Tom Sawyer. The scenes of Tom flimflamming his buddies into whitewashing a fence and Huck and Jim floating down the river to freedom on a raft easily come to mind. What doesn’t pop into our heads, however, is Mark Twain’s writings about the natural world in its myriad forms. Read any of his travel books and you will find pages, even chapters, filled with his firsthand descriptions of and reactions to Nature’s realm. -

The Story of My Life

- t7 '• 7 J^l . 9%v { s+^ The Story of My Life AMERICAN FC ' 15 NEV, , NY 10011 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/storyofmylifeOOhele Photograph by Folk, l8gS HELEN KELLER AND MISS SULLIVAN THE STORY OF MY LIFE By HELEN KELLER WITH HER LETTERS (1887—1901) AND A SUPPLEMENTARY ACCOUNT OF HER EDUCATION, INCLUDING PASSAGES FROM THE REPORTS AND LETTERS OF HER TEACHER, ANNE MANSFIELD SULLIVAN By John Albert Macy ILLUSTRATE® GARDEN CITY NEW YORK DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 1914 Copyright 1904, by The Century Company Copyright, 1902, 1903, 1905 by Helen Kelicr 4Eo ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL XXTHO has taught the deaf to speak and enabled the listening ear to hear speech from the Atlantic to the ^ockies^ 1 DeDkate this Story of My Life. EDITOR'S PREFACE THIS book is in three parts. The first two, Miss Keller's story and the extracts from her letters, form a com- plete account of her life as far as she can give it. Much of her education she cannot explain herself, and since a knowl- edge of that is necessary to an understanding of what she has written, it was thought best to supplement her autobiography with the reports and letters of her teacher, Miss Anne Mansfield Sullivan. The addition of a further account of Miss Keller's personality and achievements may be unnecessary; yet it will help to make clear some of the traits of her character and the nature of the work which she and her teacher have done.