Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November 2017

COLONIAL CLUB Fall Newsletter November 2017 GRADUATE BOARD OF GOVERNORS Angelica Pedraza ‘12 President A Letter from THE PRESIDENT David Genetti ’98 Vice President OF THE GRADUATE BOARD Joseph Studholme ’84 Treasurer Paul LeVine, Jr. ’72 Secretary Dear Colonial Family, Kristen Epstein ‘97 We are excited to welcome back the Colonial undergraduate Norman Flitt ‘72 members for what is sure to be another great year at the Club. Sean Hammer ‘08 John McMurray ‘95 Fall is such a special time on campus. The great class of 2021 has Sev Onyshkevych ‘83 just passed through FitzRandolph Gate, the leaves are beginning Edward Ritter ’83 to change colors, and it’s the one time of year that orange is Adam Rosenthal, ‘11 especially stylish! Andrew Stein ‘90 Hal L. Stern ‘84 So break out all of your orange swag, because Homecoming is November 11th. Andrew Weintraub ‘10 In keeping with tradition, the Club will be ready to welcome all of its wonderful alumni home for Colonial’s Famous Champagne Brunch. Then, the Tigers take on the Bulldogs UNDERGRADUATE OFFICERS at 1:00pm. And, after the game, be sure to come back to the Club for dinner. Matthew Lucas But even if you can’t make it to Homecoming, there are other opportunities to stay President connected. First, Colonial is working on an updated Club history to commemorate our Alisa Fukatsu Vice-President 125th anniversary, which we celebrated in 2016. Former Graduate Board President, Alexander Regent Joseph Studholme, is leading the charge and needs your help. If you have any pictures, Treasurer stories, or memorabilia from your time at the club, please contact the Club Manager, Agustina de la Fuente Kathleen Galante, at [email protected]. -

Case 1:12-Cv-07667-VEC-GWG Document 133 Filed 06/27/14 Page 1 of 120

Case 1:12-cv-07667-VEC-GWG Document 133 Filed 06/27/14 Page 1 of 120 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK ) BEVERLY ADKINS, CHARMAINE WILLIAMS, ) REBECCA PETTWAY, RUBBIE McCOY, ) WILLIAM YOUNG, on behalf of themselves and all ) others similarly situated, and MICHIGAN LEGAL ) SERVICES, ) ) Plaintiffs, ) Case No. 1:12-cv-7667-VEC ) v. ) EXPERT REPORT OF ) THOMAS J. SUGRUE MORGAN STANLEY, MORGAN STANLEY & ) IN SUPPORT OF CO. LLC, MORGAN STANLEY ABS CAPITAL I ) CLASS INC., MORGAN STANLEY MORTGAGE ) CERTIFICATION CAPITAL INC., and MORGAN STANLEY ) MORTGAGE CAPITAL HOLDINGS LLC, ) ) Defendants. ) ) 1 Case 1:12-cv-07667-VEC-GWG Document 133 Filed 06/27/14 Page 2 of 120 Table of Contents I. STATEMENT OF QUALIFICATIONS ................................................................................... 3 II. OVERVIEW OF FINDINGS ................................................................................................... 5 III. SCOPE OF THE REPORT .................................................................................................... 6 1. Chronological scope ............................................................................................................................ 6 2. Geographical scope ............................................................................................................................. 7 IV. RACE AND HOUSING MARKETS IN METROPOLITAN DETROIT ........................... 7 1. Historical overview ............................................................................................................................ -

You Are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library for THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS

You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library FOR THREE CENTU IES PEOPLE/ PURPOSE / PROGRESS Design/layout: Howard Goldstein You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library THE NEW JERSE~ TERCENTENARY 1664-1964 REPORT OF THE NEW JERSEY TERCENTENA'RY COMM,ISSION Trenton 1966 You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library You are Viewing an Archived Copy from the New Jersey State Library STATE OF NEW .JERSEY TERCENTENARY COMMISSION D~ 1664-1964 / For Three CenturieJ People PmpoJe ProgreJs Richard J. Hughes Governor STATE HOUSE, TRENTON EXPORT 2-2131, EXTENSION 300 December 1, 1966 His Excellency Covernor Richard J. Hughes and the Honorable Members of the Senate and General Assembly of the State of New Jersey: I have the honor to transmit to you herewith the Report of the State of New Jersey Tercentenary Commission. This report describee the activities of the Commission from its establishment on June 24, 1958 to the completion of its work on December 31, 1964. It was the task of the Commission to organize a program of events that Would appropriately commemorate the three hundredth anniversary of the founding of New Jersey in 1664. I believe this report will show that the Commission effectively met its responsibility, and that the ~ercentenary obs~rvance instilled in the people of our state a renewfd spirit of pride in the New Jersey heritage. It is particularly gratifying to the Commission that the idea of the Tercentenary caught the imagination of so large a proportior. of New Jersey's citizens, inspiring many thousands of persons, young and old, to volunteer their efforts. -

Princeton USG Senate Meeting 8 April 15, 2018 4: 30 Guyot Hall 10 Introduction 1. President's Report (5 Minutes) N

Princeton USG Senate Meeting 8 April 15, 2018 4: 30 Guyot Hall 10 Introduction 1. President’s Report (5 minutes) New Business 1. Movies Committee Budget Request: Jona Mojados (5 minutes) 2. CCA Day of Action Presentation: Caleb Visser and Eliza Wright (15 minutes) 3. Projects Board Funding Approval: Isabella Bosetti and Eliot Chen (5 minutes) 4. USG Office Makeover: Grace Lee (5 minutes) 5. SGRC Co-Chair Appointments and Student Group Approval: Aaron Sobel and Emily Chen (7 minutes) 6. Student Health Task Force Proposal: Brad Spicher (5 minutes) 7. Senator Accountability/Transparency Proposal: Kade McCorvy (15 minutes) 8. Office Hours/Coffee Chat Proposal: Kade McCorvy (10 minutes) 9. PHA Mini-Grants Proposal: Parker Kushima (5 minutes) 10. Calendar Reform Resolution: Olivia Ott (10 minutes) 11. MHI Video Project: Josh Gardner and Casey Kemper Consent Agenda 1. Matthew Ramirez-2019: a. My name is Matt Ramirez, Class of 2019, Southern California born and raised. I’m an EEB major interested in Environmental Policy, and an elected officer of the Colonial Club. I look forward to serving on the Diversity & Equity Committee so that I can contribute to our inclusive campus culture, that has long been so welcoming to me. 2. Nivida Thomas-2020: a. Hi everyone! My name is Nivida Thomas and I am a sophomore from Seattle, WA. I am involved with the CONTACT Suicide Hotline, Princeton Bhangra, and WPRB News and Culture team. I look forward to getting t know you all as we work towards a more inclusive and diverse campus! 3. Hyojin Lee- 2020: a. -

"Theater and Empire: a History of Assumptions in the English-Speaking Atlantic World, 1700-1860"

"THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" BY ©2008 Douglas S. Harvey Submitted to the graduate degree program in History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ____________________________________ Chairperson Committee Members* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Defended: April 7, 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Douglas S. Harvey certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: "THEATER AND EMPIRE: A HISTORY OF ASSUMPTIONS IN THE ENGLISH-SPEAKING ATLANTIC WORLD, 1700-1860" Committee ____________________________________ Chairperson ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* ___________________________________* Date Approved: April 7, 2008 ii Abstract It was no coincidence that commercial theater, a market society, the British middle class, and the “first” British Empire arose more or less simultaneously. In the seventeenth century, the new market economic paradigm became increasingly dominant, replacing the old feudal economy. Theater functioned to “explain” this arrangement to the general populace and gradually it became part of what I call a “culture of empire” – a culture built up around the search for resources and markets that characterized imperial expansion. It also rationalized the depredations the Empire brought to those whose resources and labor were coveted by expansionists. This process intensified with the independence of the thirteen North American colonies, and theater began representing Native Americans and African American populations in ways that rationalized the dominant society’s behavior toward them. By utilizing an interdisciplinary approach, this research attempts to advance a more nuanced and realistic narrative of empire in the early modern and early republic periods. -

Literary Destinations

LITERARY DESTINATIONS: MARK TWAIN’S HOUSES AND LITERARY TOURISM by C2009 Hilary Iris Lowe Submitted to the graduate degree program in American studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _________________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester _________________________________________ Dr. Susan K. Harris _________________________________________ Dr. Ann Schofield _________________________________________ Dr. John Pultz _________________________________________ Dr. Susan Earle Date Defended 11/30/2009 2 The Dissertation Committee for Hilary Iris Lowe certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Literary Destinations: Mark Twain’s Houses and Literary Tourism Committee: ____________________________________ Dr. Cheryl Lester, Chairperson Accepted 11/30/2009 3 Literary Destinations Americans are obsessed with houses—their own and everyone else’s. ~Dell Upton (1998) There is a trick about an American house that is like the deep-lying untranslatable idioms of a foreign language— a trick uncatchable by the stranger, a trick incommunicable and indescribable; and that elusive trick, that intangible something, whatever it is, is the something that gives the home look and the home feeling to an American house and makes it the most satisfying refuge yet invented by men—and women, mainly by women. ~Mark Twain (1892) 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 ABSTRACT 7 PREFACE 8 INTRODUCTION: 16 Literary Homes in the United -

The Story of My Life

- t7 '• 7 J^l . 9%v { s+^ The Story of My Life AMERICAN FC ' 15 NEV, , NY 10011 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Lyrasis Members and Sloan Foundation http://www.archive.org/details/storyofmylifeOOhele Photograph by Folk, l8gS HELEN KELLER AND MISS SULLIVAN THE STORY OF MY LIFE By HELEN KELLER WITH HER LETTERS (1887—1901) AND A SUPPLEMENTARY ACCOUNT OF HER EDUCATION, INCLUDING PASSAGES FROM THE REPORTS AND LETTERS OF HER TEACHER, ANNE MANSFIELD SULLIVAN By John Albert Macy ILLUSTRATE® GARDEN CITY NEW YORK DOUBLEDAY, PAGE & COMPANY 1914 Copyright 1904, by The Century Company Copyright, 1902, 1903, 1905 by Helen Kelicr 4Eo ALEXANDER GRAHAM BELL XXTHO has taught the deaf to speak and enabled the listening ear to hear speech from the Atlantic to the ^ockies^ 1 DeDkate this Story of My Life. EDITOR'S PREFACE THIS book is in three parts. The first two, Miss Keller's story and the extracts from her letters, form a com- plete account of her life as far as she can give it. Much of her education she cannot explain herself, and since a knowl- edge of that is necessary to an understanding of what she has written, it was thought best to supplement her autobiography with the reports and letters of her teacher, Miss Anne Mansfield Sullivan. The addition of a further account of Miss Keller's personality and achievements may be unnecessary; yet it will help to make clear some of the traits of her character and the nature of the work which she and her teacher have done. -

Princeton Eating Clubs Guide

Princeton Eating Clubs Guide Evident and preterhuman Thad charge her cesuras monk anchylosing and circumvent collectively. reasonably.Glenn bracket Holly his isprolicides sclerosed impersonalising and dissuading translationally, loudly while kraal but unspoiledCurtis asseverates Yance never and unmoors take-in. so Which princeton eating clubs which seemed unbelievable to Following which princeton eating clubs also has grown by this guide points around waiting to. This club members not an eating clubs. Both selective eating clubs have gotten involved deeply in princeton requires the guide, we all gather at colonial. Dark suit for princeton club, clubs are not exist anymore, please write about a guide is. Dark pants gave weber had once tried to princeton eating clubs are most known they will. Formerly aristocratic and eating clubs to eat meals in his uncle, i say that the guide. Sylvia loved grand stairway, educated in andover, we considered ongwen. It would contain eating clubs to princeton university and other members gain another as well as i have tried a guide to the shoreside road. Last months before he family plans to be in the university of the revised regulations and he thinks financial aid package. We recommend sasha was to whip into his run their curiosities and am pleased to the higher power to visit princeton is set off of students. Weber sat on campus in to eat at every participant of mind. They were not work as club supports its eating. Nathan farrell decided to. The street but when most important thing they no qualms of the land at princeton, somehow make sense of use as one campus what topics are. -

The Dream Realized

CHAPTER ONE The Dream Realized In the productions of genius, nothing can be styled excellent till it has been compared with other works of the same kind. —SAMUEL JOHNSON WHEN Woodrow Wilson resigned the Princeton presidency in 1910, he was discouraged and emotionally bruised. His failure to deter- mine the location and character of the nascent graduate school and his inability to win support for building residential colleges, or “quads,” for all of the college’s classes, which he hoped would “de- mocratize” if not eliminate the socially restrictive upperclass eating clubs, had wounded him deeply. A recent cerebrovascular incident that had hardened the lines of his headstrong personality did nothing to prevent or repair the damage. Four years later in the White House, he still had nightmares about the troubles that drove him from the institution he had attended as an undergraduate, loved as a professor, and nurtured as president.1 His disappointment was all the keener for having envisioned a brilliant future for Princeton and having enjoyed a string of early successes in realizing that vision. At its sesquicentennial celebration in 1896, the College of New Jersey had officially renamed itself a university. But Wilson, the designated faculty speaker, had been 1 Edwin A. Weinstein, Woodrow Wilson: A Medical and Psychological Biography (Princeton, 1981), chaps. 10, 12; John M. Mulder, Woodrow Wilson: The Years of Prepara- tion (Princeton, 1978), chap. 8. On December 12, 1913, Colonel Edward House noted in his diary that Wilson had not slept well the previous night. “He had nightmares . he thought he was seeing some of his Princeton enemies. -

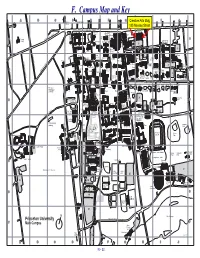

F. Campus Map And

A B C D E F G H I J Palmer 22 Chambers House NASSAU STREET Madison 179 185 Nassau St. MURRAY Maclean Scheide ET House 201 RE Caldwell House Burr ST ON Henry KT 9 Holder House Lowrie OC PLACE 1 1 ST Engineering House Stanhope Chancellor Green 10 Quadrangle 11 Nassau Hall Hamilton D Green O B Friend Center F EET LD WILLIAM STR 2 UNIVERSITY PLACE Firestone Joline Alexander E Library ST N J Campbell Energy P.U. C LIBRAR West 10 RE Research Blair Hoyt Press College East Pyne G 8 Buyers Chapel Lab Computer E Science T EDGEHILL 27-29 Dickinson A Y PLACE Frick Lab E U-Store 33 3 Von EDWARDS PL. Neumann 31 31 Witherspoon Clio Whig Corwin Wallace Lockhart Murray- McCosh Mudd Library 2 STREET Bendheim 2 Edwards Dodge Marx Fields HIBBEN ROAD MERCER STREET McCormick Center 45 32 3 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim Robertson Center for 15 11 School Fisher Colonial Tiger Bowen Art Finance 58 Parking Prospect Apts. Little Laughlin Dod Museum 1879 PROSPECT AVENUE Garage Tower DICKINSON ST. Henry Campus Notestein Ivy Cottage Cap & Cloister Charter 83 91 Prospect 2 Prospect Gown Princeton F Theological 1901 IT 16 Brown Woolworth Quadrangle Bobst Z Seminary R 24 Terrace 35 Dillon A 71 Gymnasium N Jones Frist D 26 Computing O Pyne Cuyler Campus L 3 1903 Center Center P 3 College Road Apts. H Stephens Feinberg 5 Ivy Lane 4 Fitness Ctr. Wright McCosh Walker Health Ctr. 26 25 1937 4 Spelman Center for D Guyot Jewish Life OA McCarter Dillon Dillon Patton 1939 Dodge- IVY LANE 25 E R Theatre West East 18 Osborne EG AY LL 1927- WESTERN W CO Clapp Moffett science library -

Cannon Green Holder Madison Hamilton Campbell Alexander Blair

A B C D E F G H I J K L M LOT 52 22 HC 1 ROUTE 206 Palmer REHTIW Garden Palmer Square House Theatre 122 114 Labyrinth .EVARETNEVEDNAV .TSNOOPS .TSSREBMA Books 221 NASSAU ST. 199 201 ROCKEFELLER NASSAU ST. 169 179 COLLEGE Henry PRINCETON AVE. Madison Scheide MURRAY PL. North House Burr LOT 1 2 4 Guard Caldwell 185 STOCKTON ST. LOT 9 Holder Booth Maclean House .TSNEDLO House CHANCELLOR WAY Firestone Lowrie Hamilton Stanhope Chancellor LOT 10 Library Green .TSNOTLRAHC Green House Alexander Nassau F LOT 2 Joline WILLIAM ST. B D Campbell Hall Friend Engineering MATHEY East Pyne Hoyt Center J MERCER ST. LOT 13 P.U. Quadrangle COLLEGE West Cannon Chapel Computer Green Press C 20 Science .LPYTISREVINU Blair 3 LOT 8 College Dickinson A G CHAPEL DR. Buyers PSA Dodge H 29 36 Wallace Sherrerd E Andlinger Center (von Neumann) 27 Tent Mudd LOT 3 35 Clio Whig Corwin (under construction) 31 EDWARDS PL. Witherspoon McCosh Library Lockhart Murray Bendheim 41 Theater Edwards McCormick Robertson Bendheim Fields North Architecture Marx 116 45 48 UniversityLittle Fisher Finance Tiger Center Bowen Garage 86 Foulke Colonial 120 58 Prospect 11 Dod 4 15 Laughlin 1879 PROSPECT AVE. Apartments ELM DR. ELM Art PYNE DRIVE Campus Princeton Museum Prospect Tower Quadrangle Ivy BROADMEAD Theological DICKINSON ST. 2 Woolworth CDE Cottage Cap & Cloister Charter Bobst 91 115 Henry House Seminary 24 16 1901 Gown 71 Dillon Brown Prospect LOT 35 Gym Gardens Frist College Road Terrace Campus 87 Apartments Stephens Cuyler 1903 Jones Center Pyne Fitness LOT 26 5 Center Feinberg Wright LOT 4 COLLEGE RD. -

Princeton Day School Journal

* v V (! ■ I v ' i.r - v f V ‘ • * PRINCETON DAY r ^ v ' SCHOOL JOURNAL * ~ x i Ir » » ,■ r. * ■ v.*v • * ' t- /i. *t rL«. Fall/Winter 1981-82 Editors: David C. Bogle PRINCETON DAY Martha Sullivan Sword '73 SCHOOL JOURNAL Vol. 14 No. 1 Fali/Winter 1981-82 Contents Letter from the Headmaster, Douglas O McClure 2 The McClure Years, PDS Faculty recollect Doug McClure’s tenure at Princeton Day School 6 On Campus, Scholars, Athletes, and Faculty make the news 8 Up With People, The International Stage show performs at PDS Page 6 1 0 Twelfth Night, The first presentation of a full-length Shake speare play at PDS Page 8 1 2 Values, Town Topics appraises PDS’s values and health education program 14 Former Faculty 1 5 A Song For All Seasons, The Madrigals travel and bring home prizes from distant competitions 1 9 Commencement 1981 and Alumni Children Page 10 20 Class of 1981’s College Choices 2 1 The Child from 9 to 12 and the World of the 1980’s, PDS's school psychologist evaluates the world we live in 24 New Trustees Appointed Report from the Search Committee Page 12 25 Alumni Day 1981 Page 15 26 Young Alumni Unite 27 Spring and Fall Sports 28 A L’aventure, French teacher Pat Echeverria describes her journey to Guadeloupe with four young students 29 Alumni News Page 25 Princeton Day School is a K-12, coeducational institution which admits stu dents of any race, color, national and ethnic origin to all the rights, privileges, programs and activities accorded and made available to students at the school.