The Dream Realized

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Friday, June 1, 2018

FRIDAY, June 1 Friday, June 1, 2018 8:00 AM Current and Future Regional Presidents Breakfast – Welcoming ALL interested volunteers! To 9:30 AM. Hosted by Beverly Randez ’94, Chair, Committee on Regional Associations; and Mary Newburn ’97, Vice Chair, Committee on Regional Associations. Sponsored by the Alumni Association of Princeton University. Frist Campus Center, Open Atrium A Level (in front of the Food Gallery). Intro to Qi Gong Class — Class With Qi Gong Master To 9:00 AM. Sponsored by the Class of 1975. 1975 Walk (adjacent to Prospect Gardens). 8:45 AM Alumni-Faculty Forum: The Doctor Is In: The State of Health Care in the U.S. To 10:00 AM. Moderator: Heather Howard, Director, State Health and Value Strategies, Woodrow Wilson School, and Lecturer in Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School. Panelists: Mark Siegler ’63, Lindy Bergman Distinguished Service Professor of Medicine and Surgery, University of Chicago, and Director, MacLean Center for Clinical Medical Ethics, University of Chicago; Raymond J. Baxter ’68 *72 *76, Health Policy Advisor; Doug Elmendorf ’83, Dean, Harvard Kennedy School; Tamara L. Wexler ’93, Neuroendocrinologist and Reproductive Endocrinologist, NYU, and Managing Director, TWX Consulting, Inc.; Jason L. Schwartz ’03, Assistant Professor of Health Policy and the History of Medicine, Yale University. Sponsored by the Alumni Association of Princeton University. McCosh Hall, Room 50. Alumni-Faculty Forum: A Hard Day’s Night: The Evolution of the Workplace To 10:00 AM. Moderator: Will Dobbie, Assistant Professor of Economics and Public Affairs, Woodrow Wilson School. Panelists: Greg Plimpton ’73, Peace Corps Response Volunteer, Panama; Clayton Platt ’78, Founder, CP Enterprises; Sharon Katz Cooper ’93, Manager of Education and Outreach, International Ocean Discovery Program, Columbia University; Liz Arnold ’98, Associate Director, Tech, Entrepreneurship and Venture, Cornell SC Johnson School of Business. -

Campus Vision for the Future of Dining

CAMPUS VISION FOR THE FUTURE OF DINING A MESSAGE FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR It is my sincere pleasure to welcome you to Princeton University Campus Dining. My team and I are committed to the success of our students, faculty, staff, alumni, and visitors by nourishing them to be their healthy best while caring for the environment. We are passionate about serving and caring for our community through exceptional dining experiences. In partnership with academic and administrative departments we craft culinary programs that deliver unique memorable experiences. We serve at residential dining halls, retail venues, athletic concessions, campus vending as well as provide catering for University events. We are a strong team of 300 hospitality professionals serving healthy sustainable menus to our community. Campus Dining brings expertise in culinary, wellness, sustainability, procurement and hospitality to develop innovative programs in support of our diverse and vibrant community. Our award winning food program is based on scientific and evidence based principles of healthy sustainable menus and are prepared by our culinary team with high quality ingredients. I look forward to seeing you on campus. As you see me on campus please feel free to come up and introduce yourself. I am delighted you are here. Welcome to Princeton! Warm Wishes, CONTENTS Princeton University Mission.........................................................................................5 Campus Dining Vision and Core Values .........................................................................7 -

Fea on Morrison, 'John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic'

H-New-Jersey Fea on Morrison, 'John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic' Review published on Saturday, April 1, 2006 Jeffry H. Morrison. John Witherspoon and the Founding of the American Republic. Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 2005. xviii + 220 pp. $22.50 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-268-03485-6. Reviewed by John Fea (Department of History, Messiah College) Published on H-New-Jersey (April, 2006) The Forgotten Founding Father? Americans love their "founding fathers." As most academics continue to write books that address questions related to race, class, and gender in early America, popular historians and writers (and even a few rebellious academics such as Joseph Ellis or H.W. Brands) make their way onto bestseller lists with biographies of the dead white men who were major players in America's revolutionary struggle. These include David McCullough on John Adams, Ronald Chernow on Alexander Hamilton, Ellis on George Washington, and a host of Benjamin Franklin biographies (recent works by Walter Isaacson, Edmund Morgan, Gordon Wood, Brands, and Stacy Schiff come to mind) written to coincide with the tercentenary of his birth. One of the so-called founding fathers yet to receive a recent full-length biography is John Witherspoon, the president of the College of New Jersey at Princeton during the American Revolution and the only colonial clergyman to sign the Declaration of Independence.[1] Witherspoon was a prominent evangelical Presbyterian minister in Scotland before becoming the sixth president of Princeton in 1768. Upon his arrival, he transformed a college designed predominantly to train clergymen into a school that would equip the leaders of a revolutionary generation. -

Church Will Present- Tdrug-- Abuse Movie

SOUTH BRUNSWICK, KENDALL PARK, NEW JERSEY, APRIL 2, 19.70 Newsstand 10c per copy Two suits have been filed in ~stffl5tlall5rTrrtpair thedntent and- ~ The doctrine "of res judicata fer undue hardship if he could" the Superior Court of New purpose of the zone plan and states that-a matter already re not uso the premises for his Jersey against South Brunswick zoning ordinance. solved on its merits cannot be work, in which he porforms Township as the result of zon litigated , again unless the matter light maintenance : and minor The bank contends further has been substantially changed. ing application decisions made that the Township Committee repairs on tractor-trailer at the Feb. 3 Township Commit usurped the function of the Mr. Miller contends that in trucks used to haul material tee meeting^ Board of Adjustment by con failing to approve the recom for several concerns. ducting Wo separate- public mendation of the Board of Ad The First National Bank of justment and in denying the ap The character of existing Cranbury has filed a civil ac hearings of its own in addition to the one'held by the Board of Ad plication, the Township Com uses in surrounding properties tion against the, township, the is in keeping with his property, justment. ... ............ : mittee was arbitrary, capri-_ Board of Adjustment and the -clous,- unreasonable; discrlm.- he contends, and special .rea First Charter—National—Bank- - Further, the bank says thew inatory, confiseatory-and con sons exist for grhntlngthe vari in an effort to overturn the' committee granted the variance trary to law. -

Inauguration of John Grier Hibben

INAUGURATION O F J O H N G R I E R H I B B E N PRESIDENT OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY AT RDAY MAY S U , THE ELEVENTH MCMXII INAUGURATION O F J O H N G R I E R H I B B E N PRESIDENT OF PRINCETON UNIVERSITY SATUR AY MAY THE ELE ENTH D , V MCMXII PROGRAMME AN D ORDER OF ACADEMI C PROCESSION INAUGURAL EXERCISES at eleven o ’ clock March from Athalia Mendelssohn Veni Creator Spiritus Palestrina SC RI PTUR E AN D P RAYE R HENRY. VAN DYKE Murray Professor of English Literature ADM I N I STRATI ON O F T H E OATH O F OFF I CE MAHLON PITNEY Associat e Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States D ELIVE RY O F T H E CHARTE R AN D KEYS JOHN AIKMAN STEWART e E " - n S nior Trustee, President pro tempore of Pri ceton University I NAUGURAL ADD RE SS JOHN GRIER HIBBEN President of Princeton University CONFE RR ING O F HONORARY D EGREES O Il EDWARD D OUGLASS W H I T E T h e Chief Justice of the United States WILLIAM HOWARD TAFT President of the United States T H E O N E HUND REDTH P SALM Sung in unison by choir and assembly standing Accompaniment of trumpets BENED I CT I ON EDWIN STEVENS LINES Bishop of Newark Postlude Svendsen (The audience ls re"uested to stand while the academic "rocession ls enterlng and "assing out) ALUMNI LUNCHEON T h e Gymnasium ’ at "uarter before one O clock ’ M . -

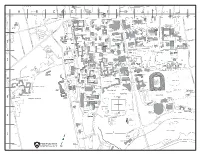

6 7 5 4 3 2 1 a B C D E F G H

LEIGH AVE. 10 13 1 4 11 3 5 14 9 6 12 2 8 7 15 18 16 206/BAYA 17 RD LANE 19 22 24 21 23 20 WITHERSPOON ST. WITHERSPOON 22 VA Chambers NDEVENTER 206/B ST. CHAMBERS Palmer AY Square ARD LANE U-Store F A B C D E AV G H I J Palmer E. House 221 NASSAU ST. LIBRA 201 NASSAU ST. NASSAU ST. MURRA 185 RY Madison Maclean Henry Scheide Burr PLACE House Caldwell 199 4 House Y House 1 PLACE 9 Holder WA ELM DR. SHINGTON RD. 1 Stanhope Chancellor Green Engineering 11 Quadrangle UNIVERSITY PLACE G Lowrie 206 SOUTH) Nassau Hall 10 (RT. B D House Hamilton Campbell F Green WILLIAM ST. Friend Center 2 STOCKTON STREET AIKEN AVE. Joline Firestone Alexander Library J OLDEN ST. OLDEN Energy C Research Blair West Hoyt 10 Computer MERCER STREET 8 Buyers College G East Pyne Chapel P.U Science Press 2119 Wallace CHARLTON ST. A 27-29 Clio Whig Dickinson Mudd ALEXANDER ST. 36 Corwin E 3 Frick PRINCETO RDS PLACE Von EDWA LIBRARY Lab Sherrerd Neumann Witherspoon PATTON AVE. 31 Lockhart Murray- McCosh Bendheim Hall Hall Fields Bowen Marx N 18-40 45 Edwards Dodge Center 3 PROSPECT FACULTY 2 PLACE McCormick AV HOUSING Little E. 48 Foulke Architecture Bendheim 120 EDGEHILL STREET 80 172-190 15 11 School Robertson Fisher Finance Ctr. Colonial Tiger Art 58 Parking 110 114116 Prospect PROSPECT AVE. Garage Apts. Laughlin Dod Museum PROSPECT AVE. FITZRANDOLPH RD. RD. FITZRANDOLPH Campus Tower HARRISON ST. Princeton Cloister Charter BROADMEAD Henry 1879 Cannon Quad Ivy Cottage 83 91 Theological DICKINSON ST. -

Princeton University, College Conversion

VSBA ILLUSTRATIONS OF SELECTED PROJECTS PRINCETON UNIVERSITY, CONVERSION TO COLLEGE SYSTEM Architects: Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates, Inc. Location: Princeton, NJ Client: Princeton University Area: 29,900 gsf (Wu); 11,000 gsf (Blair); 18,000 gsf (Little); 42,600 gsf (commons and conversion) Construction Cost: $3,143,000 (Wu); $1,724,000 (Blair); $1,300,000 (Little); $8,476,000 (commons, Forbes, landscaping, entrance, and other conversion elements) Completion: 1985 In 1980, VSBA was retained by Princeton University to conduct the school’s transformation from a dormitory to residential college system. This historic and fundamental alteration in the University’s structure (initially proposed but never implemented by Woodrow Wilson) was the result of a lengthy University-wide reappraisal of the institution’s mission and goals. The system-wide architectural changes resulting from this reappraisal encompassed new building, rehabilitation, adaptation, re-landscaping, and ornamentation involving ten buildings and complexes. VSBA’s task was to sensitively accomplish such sweeping changes endemic to Princeton’s evolving educational policy amid the school’s famous English Collegiate Gothic context, whose beauty and traditions were tied to the hearts and minds of alumni around the world. GORDON WU HALL, BUTLER COLLEGE Gordon Wu Hall provides a new focus for Butler College, one of Princeton’s three new undergraduate colleges, and houses its dining hall, lounge, library, study areas, and administrative offices. Our design problem was to create a building providing an identity for the new college and serving as a social focal point that would also connect with neighboring facilities in two stylistically disparate buildings. Furthermore, the building’s site was irregular, sloping, and narrow, and the facility was to share an existing kitchen with adjacent Wilson College. -

NJS: an Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2017 269 John Witherspoon's American Revolution Gideon Mailer Chapel Hill: University

NJS: An Interdisciplinary Journal Summer 2017 269 John Witherspoon’s American Revolution Gideon Mailer Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, 2017 440 pages $45.00 ISBN: 978-1469628189 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14713/njs.v3i2.92 On December 7, 1776, a British army brigade entered Nassau Hall, the primary building on the campus of the College of New Jersey at Princeton, and used it as a barracks and horse stable. The troops occupied this building, one of the largest in British colonial America, until George Washington’s Continental Army arrived on January 3, 1777 and drove them out of town at the Battle of Princeton. One British officer stationed in Nassau Hall would later write, “Our army when we lay there spoiled and plundered a good Library….” The damaged library belonged to Reverend John Witherspoon, the president of the college, who had fled Princeton for his own protection shortly before the arrival of British soldiers. Earlier in 1776, John Witherspoon sat in the Pennsylvania State House as a member of the New Jersey delegation to the Continental Congress. We know that he played a major role in Congress, but the destruction of his papers have prevented historians from writing the kinds of magisterial biographies of him like those published on George Washington, John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, or Thomas Jefferson. Historians do have, however, Witherspoon’s extensive published writings, allowing them to explore the depths of his religious and political thought. This is the approach that Gideon Mailer has taken in his new biography John Witherspoon’s American Revolution. -

Guide to Gender-Inclusive Housing at Princeton University Table of Contents

GUIDE TO GENDER- INCLUSIVE HOUSING AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITY TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………………………….(Pg. 2) Key Terms……………………………………………………………………………..…………………………(Pg. 2) How Can I Access Gender-Inclusive Undergraduate Housing at Princeton?...........(Pg. 2-3) How Can I Access Gender-Inclusive Graduate Housing at Princeton? ………………....(Pg. 3) Available Gender-Inclusive Undergraduate Rooms…………………………..……...……..….(Pg. 4) Resources/Contacts…………………………………………………………………………………..…(Pg. 5-6) Residential College Directors of Student Life……….………………………..…………(Pg. 5) Housing and Real Estate Services………………………………………………..…………. (Pg. 5) Other Administrative Support……………………………….……………………………. (Pg. 5-6) FAQs………………………………………………………………………..………………………………………(Pg. 6) Making This Guide Accessible……………………………………….…………………...………………(Pg. 7) Acknowledgments……………………………………………………..……………..………………..…….(Pg. 7) 1 INTRODUCTION This document is meant as a functional guide for students seeking gender-inclusive housing. We hope to provide some clarity for all students on this matter, and for trans and non-binary students in particular. The LGBT Center, the Trans Advisory Committee and Housing are working in partnership to clarify and communicate the process of applying for gender-inclusive housing and to engage other campus stakeholders to discuss future gender-inclusive housing policy changes. This guide is a first step in more broadly communicating what the policies and processes are for obtaining gender-inclusive housing. KEY TERMS “Gender-inclusive housing”* – multiple person occupancy housing that is permitted to accommodate students of different genders. “Residential College housing” – where all freshman and sophomores live, as well as some juniors and seniors, who can live in one of the three four-year residential colleges. “Upperclass housing” – junior and senior housing located outside of the four-year residential colleges. Upperclass dorms are mainly located along University Place and Elm Drive, and also include the Spelman apartments. -

Nassau Street, NW of Nassau Hall New Jersey Pitlcl^Siffcat ION ~™ Princeton University Princeton 08540 ___Mercer County C

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE New Jersey COUNTY; NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Mercer INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) C OMMON: Maclean House AND/OR HISTORIC: President's House (1756-1879) (Dean's House, 1879-1968) 12. LOG AT I pJN~ STREET AND NUMBER: Nassau Street, NW of Nassau Hall CITY OR TOWN: Princeton New Jersey Mercer pITlcL^sIFfcAT ION ~™ CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC District [3$ Building Public Public Acquisition: J£X Occupied Yes: £3$ Restricted Site Q Structure Private || In Process II Unoccupied | | Unrestricted Q Object Both Q Being Considered Q Preservation work i n progress n NO PRESENT USE ( Check One or More as Appropriate) HI Agricultural F_7I Government D Pork [ 1 Transportation | | Comments | | Commercial [_) Industrial (JCXPrivate Residence [U Other (Specify) [Xl Educational [3] Military [31 Religious [~] Entertainment [3] Museum L~] Scientific OWNER'S NAME: Princeton University STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Princeton 08540 New Jersey TEGALOESCRlFrToN™ COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: ________Mercer County Court House STREET AND NUMBER: South Broad Street CITY OR TOWN: Trenton New Jersey . REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Historic American Buildings Survey (9 sheets and 2 photos) DATE OF SURVEY: 1935-36 Federa i State [ | County [_] Local DEF-'OSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Division of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress STREET AND NUMBER: CITY OR TOWN: Washington D.C. 7, "DESCRIPTION (Check One) Exce llent Good Deteriorated CH Ruins dl Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) Altered G Unaltered Moved QJ Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Designed and constructed by Robert Smith of Philadelphia, the President's House, as built in 1756, was a brick two-story gable-roofed rectangular structure with a one-story polygonal bay extending from the west side near the southwest (rear) corner. -

The Princeton Seminary Bulletin

Catalogue of Princeton Theological Seminary 1923-1924 ONE HUNDRED AND TWELFTH YEAR The Princeton Seminary Bulletin Volume XVII, No. 4, January, 1924 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Princeton Theological Seminary Library https://archive.org/details/princetonsemina1741prin_0 4. President Stevenson, 86 Mercer St 15. Dr. Wilson, 73 Stockton St. 5. Dr. Loetscher, 98 Mercer St. 17. Dr. Dulles, 27 Boudinot St. 6. Dr. Hodge, 80 Mercer St 18. Dr. Machen, 39 Alexander Hall. 7. Dr. Armstrong, 74 Mercer St 19. Dr. Allis, 26 Alexander Hall. 8. Dr Davis, 58 Mercer St. 20. Missionary Apartment, 29 Alexander St. 9. Dr. Vos, 52 Mercer St. 21. Calvin Payne Hall. 10. Dr. J. R. Smith, 31 Alexander St. Mr. Jenkins, 309 Hodge Hall. 11. Mr. H. W. Smith, 16 Dickinson St. Mr. McCulloch, Calvin Payne Hall, Al. Catalogue of The Theological Seminary of The Presbyterian Church at Princeton, N. J. 1923-1924 One Hundred and Twelfth Year The Princeton Seminary Bulletin Vol. XVII, January, 1924, No. 4 Published quarterly by the Trustees of the Theological Seminary of the Presbyterian Church. Entered as second class matter. May. 1907, at the post^'office at Princeton, N. J. under the Act of Congress of July 16, 1894. 3 BOARD OF DIRECTORS MAITLAND ALEXANDER, D.D., LL.D., President Pittsburgh JOHN B. LAIRD, D.D., First Vice-President Philadelphia ELISHA H. PERKINS, Esq., Second Vice-President Baltimore SYLVESTER W. BEACH, D.D., Secretary Princeton J. ROSS STEVENSON, D.D., LL.D., ex-officio Princeton Term to Expire May, 1924 HOW.\RD DUFFIELD, D.D New York City WILLIAM L. -

Introduction

PART I Introduction CHAPTER 1 THE SEARCH FOR AN ALTERNATIVE AFFIRMATIVE ACTION POLICY The Search for an Alternative Affirmative Action Policy in American Higher Education In 1973 and 1974, a white U.S. military veteran named Allan Bakke applied to medical school at the University of California–Davis (UC Davis) and was twice rejected. At the time the student bodies of most American colleges and universities were overwhelmingly white, especially the professional schools, such as law and medical schools. In an attempt to remedy the underrepresen- tation of minorities, UC Davis had established an affirmative action program in the early 1970s, with the multiple goals of “reducing the historic deficit of traditionally disfavored minorities in medical schools and in the medical pro- fession,” “countering the effects of societal discrimination, increasing the number of physicians practicing in underserved communities,” and “obtain- ing the educational benefits that flow from an ethnically diverse student body.”1 In furtherance of these aims, the medical school at UC Davis created two separate admission pools: one for standard applicants and another for minority applicants. Sixteen of the one hundred seats in the entering class were reserved for the latter group.2 Bakke was born in Minneapolis in 1940 to a middle-class family of Scan- dinavian descent and was raised in Florida. His father was a postal carrier and his mother was a schoolteacher. He received a bachelor’s degree in engineer- ing from the University of Minnesota in 1962 and joined the U.S. Marine Corps after graduation. He served as an engineer in the Marines for four years, including a seven- month stint in Vietnam, earning the rank of captain.